Peace of Ryswick

The Peace of Ryswick, or Rijswijk, was a series of treaties signed in the Dutch city of Rijswijk between 20 September and 30 October 1697. They ended the 1688 to 1697 Nine Years' War between France, and the Grand Alliance, which included England, Spain, Austria, and the Dutch Republic.

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

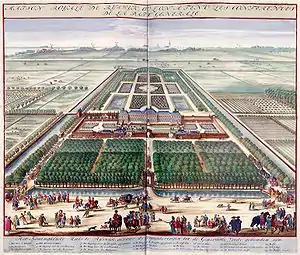

Huis ter Nieuwburg, location for the negotiations | |

| Context | End of the 1689–1697 Nine Years War; King William's War |

| Signed | 20 September 1697 |

| Location | Rijswijk |

| Negotiators | |

| Signatories | |

| Parties | |

| Language | French |

One of a series of wars fought by Louis XIV of France between 1666 to 1714, neither side was able to make significant territorial gains. By 1695, the huge financial costs, coupled with widespread famine and economic dislocation, meant both sides needed peace. Negotiations were delayed by the question of who would inherit the Spanish Empire from the childless and terminally-ill Charles II of Spain, the closest heirs being Louis and Leopold.

Since Louis could not impose his preferred solution, he refused to discuss the issue, while Leopold refused to sign without its inclusion. He finally did so with great reluctance on 30 October 1697, but the Peace was generally viewed as a truce; Charles' death in 1701 led to the War of the Spanish Succession.

In Europe and North America, the terms essentially restored the position prevailing before the war, while Spain ceded the islands of Tortuga and Saint-Domingue. France also evacuated territories occupied since the 1679 Treaty of Nijmegen, including Freiburg, Breisach, Philippsburg, and the Duchy of Lorraine.

Background

The Nine Years' War was financially crippling for its participants, partly because armies increased in size from an average of 25,000 in 1648, to over 100,000 by 1697. This was unsustainable for pre-industrial economies; the war absorbed 80% of English state revenue in the period, while the huge manpower commitments badly affected the economy.[1]

The 1690s also marked the lowest point of the so-called Little Ice Age, a period of cold and wet weather affecting Europe in the second half of the 17th century. Harvests failed throughout Europe in 1695, 1696, 1698 and 1699; in Scotland and parts of Northern Europe, an estimated 5–15% of the population starved to death.[2]

Although fighting largely ended in Europe after 1695, the subsidiary conflict known as King William's War continued in the Americas. A French fleet arrived in the Caribbean in early 1697, threatening the Spanish treasure fleet, and English possessions in the West Indies.[3] England occupied the whole of Nova Scotia, while the French repulsed attacks on Quebec, captured York Factory, and caused substantial damage to the New England economy.[4]

Negotiations

Talks were dominated by the primary issue of European politics for the last 30 years; the Spanish inheritance. By 1696, it was clear Charles II of Spain would die childless, and his potential heirs included King Louis XIV of France and Emperor Leopold I. The Spanish Empire remained a vast global confederation; in addition to Spain, its territories included large parts of Italy, the Spanish Netherlands, the Philippines, and much of the Americas. Acquisition by either France or Austria would change the European balance of power.[5]

Recognising he was not strong enough to impose his preferred solution to the Spanish question, Louis wanted to prevent its discussion, by dividing the Grand Alliance, and isolating Leopold. The 1696 Treaty of Turin made a separate peace with the Duchy of Savoy.[6] Other concessions were the return of the Duchy of Luxemburg to Spain; considerably larger than the modern state, it was essential to Dutch security. He also agreed to recognise William III as monarch of England and Scotland, rather than the exiled James II.[7]

Formal discussions between the delegations were held in the Huis ter Nieuwburg at Ryswick, mediated by Swedish diplomat and soldier Baron Lilliënrot. Many members of the Empire, such as Baden and Bavaria, sent representatives, although they were not party to the treaties.[8]

Talks proceeded slowly; Leopold habitually avoided making decisions until absolutely necessary, and unless the treaty addressed the inheritance question, he would only agree to a ceasefire. One of the Spanish negotiators, Bernardo de Quiros, ignored instructions from Madrid to make peace at any price, and agreed to support this demand.[9] Anxious to finalise peace, William and Louis appointed the Earl of Portland and Marshal Louis-François de Boufflers as their personal representatives; they met privately outside Brussels in June 1697, and quickly finalised terms, with de Quiros being over-ruled.[10]

The Peace consisted of a number of separate agreements; on 20 September 1697, France signed Treaties of Peace with Spain and England, a Ceasefire with the Holy Roman Empire, and on 21 September, a Treaty of Peace and Commerce with the Dutch Republic.[11]

Leopold delayed signing the Peace, when Charles fell seriously ill; one frustrated negotiator claimed 'it would be a shorter way to knock (Charles) on the head, rather than all Europe be kept in suspense.'[12] The Spanish king recovered, while William threatened to dissolve the Alliance if Leopold did not sign a peace agreement before 1 November; he finally did so on 30 October.[13]

Provisions

The treaty restored the position to that agreed by the 1679 Treaty of Nijmegen; French kept Strasbourg, strategic key to Alsace-Lorraine, but returned other territories occupied since then, including Freiburg, Breisach, Philippsburg and the Duchy of Lorraine to the Holy Roman Empire. They evacuated Catalonia, Luxembourg, Mons and Kortrijk in the Spanish Netherlands, while the Dutch were allowed to place garrisons in Namur and Ypres. Louis recognised William as king, withdrew support from the Jacobites, and abandoned claims to the Electorate of Cologne, and the Electoral Palatinate.[14]

In North America, positions returned to those prevailing before the war, although in reality low-level conflict persisted around the boundaries. In the Caribbean, France received the Spanish islands of Tortuga and Saint-Domingue, while the Dutch returned their colony of Pondichéry in India.[14]

Aftermath

All sides recognised Ryswick was a truce, and conflict would resume when Charles died, but the Nine Years' War demonstrated France could no longer impose its objectives without allies. Louis therefore adopted a dual-track approach of a diplomatic offensive to seek support, while keeping the French Army on a war footing. The increase in Habsburg power following victory in the Great Turkish War was offset by the growing independence of states like Bavaria, which looked to Louis for support, rather than Leopold.[15]

The war diverted resources from both the Dutch and French navies, and although the Dutch still dominated the Far East trade, Ryswick marked a turning point in England's rise as a global maritime power. Previously focused on the Levant, its mercantile interests began challenging Spanish and Portuguese control of the Americas, where the French could not compete. However, the determination of the Tory majority in Parliament to reduce costs meant that by 1699, the English army was reduced to less than 7,000 men.[16]

This seriously undermined William's ability to negotiate on equal terms with France, and despite his intense mistrust, he co-operated with Louis in an attempt to agree a diplomatic solution to the Succession. The so-called Partition Treaties of The Hague in 1698, and London in 1700, ultimately failed to prevent the outbreak of war in 1702.[17]

The huge debts accumulated by the Dutch weakened their economy, while London replaced Amsterdam as the commercial centre of Europe. Followed by the 1701–1714 War of the Spanish Succession, it marked the end of the Dutch Golden Age.[18]

References

- Childs 1991, p. 1.

- White 2011, pp. 542–543.

- Morgan 1931, p. 243.

- Grenier.

- Storrs 2006, pp. 6–7.

- Frey & Frey 1995, pp. 389–390.

- Szechi 1994, p. 51.

- SW 1732, pp. 380–381.

- Childs 1991, p. 340.

- Frey & Frey 1995, p. 389.

- Israel 1967, pp. 145–176.

- Morgan 1931, p. 241.

- Morgan 1931, p. 242.

- Onnekink 2018, pp. 1–4.

- Thomson 1968, pp. 25–34.

- Gregg 1980, p. 126.

- Falkner 2015, p. 37.

- Meerts 2014, pp. 168–169.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Treaty of Ryswick. |

- Treaty of Ryswick, English translation

- Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688–1697: The Operations in the Low Countries (2013 ed.). Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719089961.

- Falkner, James (2015). The War of the Spanish Succession 1701-1714. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781473872905.

- Frey, Linda; Frey, Marsha (1995). The Treaties of the War of the Spanish Succession: An Historical and Critical Dictionary. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0313278846.

- Gregg, Edward (1980). Queen Anne (Revised) (The English Monarchs Series) (2001 ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300090246.

- Grenier, John. "King William's War; New England's Mournful Decade". Historynet. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- Israel, Fred (1967). Major Peace Treaties of Modern History, 1648–1967 Volume I (2001 ed.). Chelsea House Publications. ISBN 978-0791066607.

- Meerts, Paul Wilson (2014). Diplomatic negotiation: Essence and Evolution (PhD). Leiden University.

- Morgan, WT (1931). "Economic Aspects of the Negotiations at Ryswick". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 14. JSTOR 3678514.

- Onnekink, David (2018). Martell, Gordon (ed.). The Treaty of Ryswick in The Encyclopedia of Diplomacy Volume III. Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1118887912.

- Storrs, Christopher (2006). The Resilience of the Spanish Monarchy 1665-1700. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0199246373.

- SW (1732). A General Collection of Treatys, Volume I. Knapton.

- Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688-1788. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719037740.

- Thomson, Mark (1968). William III and Louis XIV; Essays 1680-1720. Liverpool University Press.

- White, ID (2011). Lynch, M (ed.). Rural Settlement 1500–1770 in The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. OUP. ISBN 978-0199693054.