Peasant Corporation

The Peasant Corporation (French: Corporation paysanne) was a Paris-based organization created by the Vichy France government during World War II (1939–45) to support a corporatist structure of agricultural syndicates. The Ministry of Agriculture was unenthusiastic and undermined the Corporation, which was launched with a provisional structure in 1941 that was not finalized until 1943. By then the small farmers and farm workers had become disillusioned since the Corporation had maintained the privileged position of landowners and had not protected them from demands by the increasingly unpopular German occupiers. The Corporation, which was never effective, was dissolved after the liberation of France in September 1944.

Corporation paysanne | |

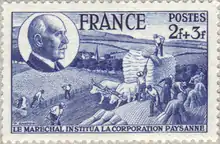

Postage stamp of 24 April 1944 celebrating launch of the corporation. Marshal Philippe Pétain is depicted in the top-left. | |

| Formation | 1941–43 |

|---|---|

| Dissolved | 1944 |

| Type | Agrarian union |

| Purpose | Organize mutual support of agricultural workers, farmers, artisans and landowners |

| Headquarters | Paris, France |

Charter

The Peasant Corporation had its roots in the rural Syndicats Agricoles, whose Union Centrale des Syndicats Agricoles (UCSA) became the Union Nationale des Syndicats Agricoles (UNSA) in 1934 when Jacques Le Roy Ladurie became its secretary general.[1] Louis Salleron played a leading role in defining the structure of the Corporation.[2] As the semi-official theoretician of the UNSA he was the main author of the draft law of September 1940 on the Corporation Paysanne, which would create a corporatist structure in agriculture.[3]

The broad concept was that each community would have a "corporative syndicate" of all peasant families, grouped into regional "corporative unions" which would assign delegates to meet periodically in a National Corporative Council.[4] In parallel, and subordinate to the Corporation, there would be various unified professional groups including cooperatives, mutual insurance and credit funds, and specialized groups for each of the main agricultural products.[5] The Corporation would be "a decentralized organization possessing disciplinary powers." Political and social divisions would be eliminated by creating a single syndicate in each commune that would include landowners, tenant farmers, sharecroppers, farmworkers and artisans.[4]

After many revisions and some objections from the Germans the Peasant Charter was promulgated on 2 December 1940.[4] Pierre Caziot was Minister of Agriculture and Supplies from 12 July 1940 to 6 September 1940, then Secretary of State for Agriculture and Supplies from 6 September 1940 to 13 December 1940 in the government of Marshal Philippe Pétain.[6] He was Minister and Secretary of State for Agriculture from 13 December 1940 to 18 April 1942 in the governments of Pétain and François Darlan.[6] Caziot promulgated the law of 2 December 1940 that organized the Peasant Corporation.[7] Although he was in favor of a national peasant organization, Caziot accepted the word "corporation" only at Pétain's insistence.[8]

Organizing commission

Caziot lacked enthusiasm for corporatism and delayed implementation of the Peasant Corporation.[8] The Commission d'Organization Corporative (COC) was established on 21 January 1941 as an agency to construct the Peasant Corporation.[8][9] The commission, headed by Count Hervé Budes de Guébriant, was mostly made up of leading conservative landowners and took nearly two years to develop the legislation that became effective on 16 December 1942.[10] De Guébriant and his main associate Rémy Goussault identified "corporatist" local agrarian organizations, which would become the departmental branches of the corporation. They excluded organizations associated with the Left in the Third Republic. They favored traditional notables as regional Corporation heads (syndics) for each department, but included four followers of Henry Dorgères who had strong local support.[11] When elections were introduced for Corporation leaders, in some cases peasants were elected in place of large landowners.[12] However, the Dorgérists did not gain an important role in the Corporation.[13]

In 1941–44 Adolphe Pointier, a large-scale wheat and sugar beet farmer in the Somme department, was syndic national or chief executive of the corporation.[14] Louis Salleron was made the Corporation's delegate-general for economic and social questions.[15] On 15 July 1941 Dorgères was made delegate-general of propaganda of the Corporation.[16] Henri de Champagny was second in command of the organizational committee launched in September 1941 to develop the Corporation's structures.[12] The corporation struggled to become effective, handicapped by a temporary structure, internal conflicts, and actions by the Ministry of Agriculture that reduced its authority and introduced reforms without consultation.[15] By the end of the first year Salleron gave vent to his frustration,

The struggle is ... open between the old cadres and the new principles. The truth forces us to say that the first year's experience of the Peasant Corporation marks a clear-cut success for statism. The Corporation is practically without financial resources, and, in its every move, it is kept on leading strings by the administration. This grave fact must be brought to the attention of the peasant world. If, in fact, the Corporation does not become the peasants' instrument of liberation, it will be the most perfect instrument of oppression one can imagine.[17]

In response, Salleron was dismissed from his position in the Corporation in late 1941, and his weekly journal Syndicats paysans was closed soon after.[17]

Caziot was succeeded as Minister of Agriculture on 18 April 1942 by Jacques Le Roy Ladurie, who was also a passionate agrarian.[10] Max Bonnafous assisted Le Roy Ladurie as Secretary of State for Agriculture and Supplies.[18] Le Roy Ladurie soon came into conflict with Pierre Laval over German demands for workers and agricultural produce.[17] He resigned in frustration on 11 September 1942.[19] Bonnafous succeeded him as Minister and Secretary of State for Agriculture and Supplies until 6 January 1944 in Laval's 2nd cabinet.[18] Bonnafous tried to speed up the formal creation of the Peasant Corporation, which would unite rural producers in France and give them the apparatus of self-government.[20] In December 1942 Bonnafous told a German official, "So far the Peasant Corporation has been merely an organization for peasant demagoguery, and has handicapped the government. It has been necessary to convert it into an organization that helps the government.[21]

Operations

The body that was eventually established in 1943 no longer had broad support among the peasants and was too late to make any real change.[20] The German occupation and internment of many farm workers in prison camps had made the peasants sympathetic to the French Resistance.[22] With growing requisitions of food by the Germans and shortages of food in the cities, the Peasant Corporation became a state bureaucracy for the control of prices and supply.[22] In December 1943 Pointier told a meeting of 500 syndics from Indre-et-Loire that the corporation must be "the voluntary auxiliary of the Ravitaillement service ... It is up to us to make sure that quotas are delivered on time and not to leave this to the gendarmerie or the price-control bodies, which have their own duties. The corporation has one immediate interest: to ensure that an unbridgeable gulf does not open up between the urban and peasant populations."[12]

The rural communities became hostile to the Peasant Corporation and avoided or rejected the official controls, which the government could not enforce.[22] The Germans disliked the Corporation, finding it was not sufficiently collaborationist, while the government spent its energy promoting the corporation rather than making it effective. Vichy received valid criticism for preserving the privileges of the large landowners and aristocrats at the expense of the peasants, who were supposed to be among the nation's "vital forces".[22]

The Peasant Corporation was dissolved after the Liberation of France in September 1944, but the unity of agricultural organizations that it had established persisted.[23] The new socialist Minister of Agriculture, François Tanguy-Prigent, replaced it with a national union of working farmers rather than landowners, the General Confederation of Agriculture (GCA). In March 1946 the CGA became the Fédération nationale des syndicats d'exploitants agricoles (FNSEA).[24] Many of the former Peasant Corporation leaders became leaders of the FNSEA.[23]

Notes

- Paxton 1997, p. 45.

- Guillaume Gros 2011.

- Wright 1964, pp. 77–78.

- Wright 1964, p. 79.

- Wright 1964, pp. 79–80.

- Pierre CAZIOT – Ministère de l’agriculture.

- Caziot Pierre – B&S.

- Lackerstein 2013, p. 97.

- Paxton 1997, p. xi.

- Moulin 1991, p. 152.

- Paxton 1997, p. 120.

- Gildea 2013, p. 112.

- Paxton 1997, p. 144.

- Paxton 1997, p. 82.

- Wright 1964, p. 83.

- Paxton 1997, p. 148.

- Wright 1964, p. 84.

- Max BONNAFOUS – Ministère de l’agriculture.

- Collectif 2005.

- Lackerstein 2013, pp. 97–98.

- Wright 1964, p. 225.

- Lackerstein 2013, p. 98.

- Paxton 1997, p. 149.

- Gildea 2013, p. 361.

Sources

- "Caziot Pierre". B&S Encyclopédie (in French). B&S Editions. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- Collectif (2005). "Le Roy Ladurie (Jacques Jules Marie Joseph)". Dictionnaire des parlementaires français de 1940 à 1958 (in French). Paris: La Documentation française. ISBN 2-11-005990-7. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- Gildea, Robert (2013-07-30), Marianne in Chains: Daily Life in the Heart of France During the German Occupation, Henry Holt and Company, ISBN 978-1-4668-5021-7, retrieved 2016-03-04

- Guillaume Gros (2011), "Le corporatisme de Louis Salleron. Olivier Dard", Convergences (in French), Metz: Peter Lang, retrieved 2016-03-03

- Lackerstein, Debbie (2013-07-28), National Regeneration in Vichy France: Ideas and Policies, 1930–1944, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 978-1-4094-8297-0, retrieved 2016-03-04

- Max BONNAFOUS (in French), Ministère de l’agriculture, de l’agroalimentaire et de la forêt, 2012-08-31, retrieved 2016-01-02

- Moulin, Annie (1991-10-24), Peasantry and Society in France Since 1789, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-39577-9, retrieved 2015-12-07

- Paxton, Robert O. (1997-09-26), French Peasant Fascism : Henry Dorgeres' Greenshirts and the Crises of French Agriculture, 1929-1939: Henry Dorgeres' Greenshirts and the Crises of French Agriculture, 1929-1939, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN 978-0-19-535474-4, retrieved 2016-03-03

- "Pierre CAZIOT" (in French). Ministère de l’agriculture, de l’agroalimentaire et de la forêt. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- Wright, Gordon (1964), Rural Revolution in France: The Peasantry in the Twentieth Century, Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0-8047-0190-7, retrieved 2015-12-27