Percy Charles Pickard

Group Captain Percy Charles "Pick" Pickard, DSO & Two Bars, DFC (16 May 1915 – 18 February 1944) was an officer in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. He served as a pilot and commander, and was the first officer of the RAF to be awarded the DSO three times during the Second World War.[1] He flew over a hundred sorties and distinguished himself in a variety of operations requiring coolness under fire. Some consider Pickard of the same calibre as Guy Gibson and Leonard Cheshire.[2]

Percy Charles Pickard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | "Pick" |

| Born | 19 May 1915 Handsworth, Sheffield, West Riding of Yorkshire, England |

| Died | 18 February 1944 (aged 28) Amiens, France |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ | Royal Air Force |

| Years of service | 1937–1944 |

| Rank | Group Captain |

| Commands held | No. 140 Wing RAF No. 51 Squadron No. 161 Squadron |

| Battles/wars | Second World War |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Order & Two Bars Distinguished Flying Cross Mentioned in Despatches Czechoslovak War Cross 1939 |

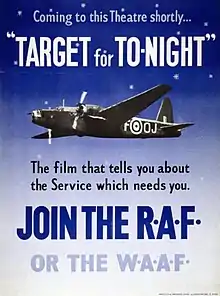

In 1941 he participated in the making of the 1941 wartime film Target for To-night, which made him a public figure in England. He led the squadron of Whitley bombers that carried paratroopers to their drop for the Bruneval raid.

Throughout 1943 he flew the Lysander on nighttime missions into occupied France for the SOE, performing insertions of agents and picking up personnel from very small landing strips. Pickard led a group of Mosquitos on the Amiens raid, in which he was killed in action 18 February 1944.

Background

Pickard was born in Handsworth, Sheffield, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, England and was educated at Framlingham College. Academically he did not excel, but was a skilled equestrian and shot.[3] Pickard was the son of the late P. C. Pickard and Mrs. J. Pickard. He was the youngest of two boys and three girls. His sister was actress Helena Pickard, married to English actor Sir Cedric Hardwicke.[3] She gave birth to the actor Edward Hardwicke, one of the stars of Colditz and later Dr Watson of Sherlock Holmes fame who also served in the RAF as a pilot during his national service.[4]

During the 1930s, Pickard spent some time living on a ranch in Kenya. He enjoyed hiking in the African bush and indulged his passion for riding horses and shooting. At the same time he discovered polo, a sport he quickly became skilled at. His first taste of service came when he enlisted in the King's African Rifles as a reservist. Unfortunately, Pickard contracted malaria but recovered and returned to England.[5]

Service history

After Pickard failed to qualify as an army officer,[6] he was accepted and received a short service commission into the Royal Air Force in January 1937,[7] which was made Permanent in November.[8] After successfully passing his flight training with an 'above average' rating, he was posted to 214 Squadron, flying the Handley Page Harrow.[9] His skill as a pilot was soon noticed, and he was appointed personal assistant to the air officer commanding a training group at Cranwell in 1938. He participated in fighting over Norway, France and during the Dunkirk evacuation.[3] He married Dorothy at this time, despite her family's misgivings. They had one child together, a son named Nicholas Charles Pickard. [10]

During the Battle of Britain while serving as a flight lieutenant in No. 99 Squadron, Pickard flew the Vickers Wellington in raids on Germany, where he began to work with his longtime navigator Flt Sgt Alan Broadley.[11] Involved with early leaflet dropping sorties during the phony war, Pickard flew alongside Jack Grisman of Great Escape fame.[12] While posted to 99, Pickard also flew six missions with David Holford, who served as co-pilot. He rated Holford as a talented pilot.[13]

On 19 June 1940 while on the return from a raid, he was forced to ditch his flak damaged Wellington in the English Channel. He and his crew survived and were picked up by a lifeboat shortly afterwards.[2] He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) in July 1940.

He was promoted to squadron leader with No. 311 (Czechoslovak) Squadron and was awarded a Distinguished Service Order (DSO) in March 1941. Pickard was drafted in to the squadron to improve performance and bring the unit up to operational standards. Preferring an informal approach, he was often seen wearing cowboy boots with his uniform and accompanied by his sheepdog Ming.[14] As an officer, Pickard was mild mannered, approachable and humourous but determined in the face of action, leading him to be popular with his men.[2]

He was awarded the Czechoslovak War Cross in 1941.[15]

Target for Tonight

Pickard appeared as Squadron Leader Dickson in the RAF propaganda film Target for Tonight, released in July 1941. The plot concerned a Wellington bomber, F for Freddie taking part in a night time raid over Germany which is damaged during its return flight to England.

Pickard was initially reluctant to appear. The film was produced by the Royal Air Force Film Production Unit and directed by Harry Watt. It was seen as a way to encourage people to join the service. It was a box office hit and won an Academy Award in 1942.[16]

Watt later expressed regret that most of the people featured in the film did not survive the war.[17]

Special operations

In May 1942, as wing commander in charge of No. 51 Squadron based at RAF Dishforth, he was awarded a bar to the DSO in recognition of his leadership in Operation Biting (also known as the Bruneval raid) on 27 February 1942.[18] Pickard's role was to fly in and allow members of the British 1st Airborne Division to parachute behind enemy lines from a Whitley bomber to capture and retrieve a Wurzburg radar installation. The raid was a complete success.[19] After the raid, the King and Queen visited Dishforth. Upon asking why there were two footprints on the ceiling of the mess, Pickard with total honesty explained that the post raid party had led to hi-jinks and the footprints were his.[20]

_and_Special_Forces_Agents_during_the_Second_World_War_HU98865.jpg.webp)

No. 161 Squadron missions

October 1942 saw Pickard posted to No. 161 Squadron. In March 1943, while commanding 161 – which carried out operations in support of the SOE in occupied Europe – at RAF Tempsford he was awarded a second bar to the DSO for outstanding leadership ability and fine fighting qualities.[21] Flying Westland Lysanders, he was involved in flying British agents and supplies both in and out of occupied Europe on behalf of the SOE alongside Hugh Verity.[22]

Pickard had a talented team of pilots under his command, including Frank Rymills, Peter Vaughan-Fowler and Jim McCairns.[23] Pickard specialised in 'moonlight operations,' flying spies and materiel on a night of the full moon. On one flight in November 1942 he did not receive the expected signal from the ground so that he could land, and had to flee when attacked by two Luftwaffe fighters. Using the Lysander's superior handling and slower speed, Pickard managed to escape back to England despite being repeatedly fired upon and chased across the English Channel.[24] On another occasion, he rescued seven agents and managed to take off despite the agents being closely hunted by the Gestapo.[25]

One of the agents Pickard worked with was Henri Déricourt, who was suspected in some quarters of being a double agent, although he was later acquitted.[26]

Hudson flights

Working with Verity, the two pushed for the Lockheed Hudson to be introduced for SOE work to give greater flexibility and be able to transport more passengers then the Lysander could offer. The two men then worked out the logistics of operating the Hudson from the French fields which were still Nazi occupied.[27] The Hudson went into operational service with 161 on 13 February 1943. The first mission, flown by Pickard delivered five agents into France. In all, the Hudson flew 36 successful sorties without loss, delivering 139 agents and extracting 221, although several early fights in early 1943 saw Pickard operating with his wrist in a plaster cast, the result of more riotous parties in the mess hall.[28]

A sortie to pick up two operatives led to Pickard's aircraft to become stuck in mud on landing. It took the three men with help from several people in a local village to free the aircraft for take off, but the mission led to Pickard being awarded a second bar to his DSO, making him the first RAF officer in the Second World War to be awarded as such.[29]

Pickard recommended one of his pilots, Flt Lt Geoffrey Osborn be recommended for the George Medal after Osborn's aircraft crashed and he single handedly rescued several members of his crew from the burning plane. Osborn was given the award.[30]

During the early planning for Operation Chastise, Guy Gibson sought Pickard's help to plan the route for the mission. 617 Squadron's commander valued Pickard's knowledge and experience, and he was able to provide Gibson with details of the position of the German flak batteries. This proved invaluable and allowed Gibson to plot a course that avoided the majority of the flak posts.[31]

No. 140 Wing

For a while Pickard was station commander at RAF Sculthorpe. In October 1943 he was given command of No. 140 Wing of the Second Tactical Air Force by Basil Embry. This put him in charge of three squadrons of de Havilland Mosquito fast bombers. They became specialised in low level precision attacks.[32]

On 3 October, Pickard led 12 Mosquitos on an attack against the Pont Chateau power station. The power station was badly damaged and all 12 aircraft returned to base safely.[33]

When Leonard Cheshire was trying to convince his superiors to use the de Havilland Mosquito as a low level marking aircraft to assist 617 Squadron, he approached Pickard for help. Cheshire had just taken command of the Dambusters, who were in a slump after their success with the Ruhr dams raid and the departure of Gibson.[34] On 19 December 1943, Cheshire visited Pickard and the two men went over the merits of the aircraft. Pickard took Cheshire up for a short test flight to demonstrate how good the Mosquito was. Impressed, he was eventually able to obtain the Mosquito for his squadron's use and it was used to good effect, initially with Cheshire flying as the marking pilot.[35]

Amiens Raid

No. 140 Wing was tasked with Operation Jericho. Embry was initially earmarked in to lead the raid, but he stepped aside. This allowed Pickard to take command of 18 February 1944 low-level attack on the Amiens Prison, despite having limited experience with low level operations[36][lower-alpha 1] Each Mosquito squadron was to have an escort of one Hawker Typhoon squadron, 174 Squadron and 245 Squadron from RAF Westhampnett and a squadron provided by Air Defence of Great Britain (the part of Fighter command not transferred to the 2nd Tactical Air Force) from RAF Manston.[38] The attack was carried out at the request of the French resistance in order to allow a considerable number of their imprisoned members, who were soon to be executed by the occupying Nazis, the chance to escape. The Resistance stated that the prisoners had said they would rather take the chance of being killed by RAF bombs than be shot by the Nazis.[39]

[[File:Operation Jericho - Amiens Jail During Raid 1.jpg|thumb|{{centre|487 Squadron Mosquitos over Amiens Prison as their bombs explode, showing the snow-covered buildings and landscape.[lower-alpha 2]]] At the end of the mission briefing, Pickard was quoted as saying 'It's a death or glory job, boys.'[41] The whole mission was flown at tree top height, with precision bombing required. Operation Jericho was a success; the prison walls were breached and prison buildings and guards' barracks were destroyed. Of the 832 prisoners, 102 were killed by the bombing, 74 were wounded and 258 escaped, however two-thirds of the escapees were later recaptured.[42]

Aftermath

Pickard, together with his Navigator, Flight Lieutenant J. A. "Bill" Broadley, were killed when their Mosquito, HX922/"EG-F", was shot down by a Fw 190 flown by Feldwebel Wilhelm Mayer of 7. Staffel Jagdgeschwader 26 in the closing stages of the operation. Pickard and Broadley were initially reported missing and then in September 1944 it was announced that they had been 'killed in action'.[3]

Pickard is buried in plot 3, row B, grave 13 at St Pierre Cemetery near Amiens, France.[43] Broadley is buried in plot 3, row A, grave 11 of the same cemetery. Pickard's death left Dorothy to bring up their young son on her own.[3]

The French government called for him to receive a posthumous Victoria Cross.[44] Lord Londonderry advocated for Pickard to receive the award, however Basil Embry declined to support this, stating that the Amiens raid was a standard operation and did not warrant it. He felt that Pickard's other awards justified the decision for him to not receive the VC.[45] The French also sought to award Pickard the Légion d’Honneur and the Croix de Guerre, but this was not permitted as British policy did not allow acceptance of posthumous awards from foreign countries. Pickard's family have continued to petition to allow the awards.[46]

No. 140 Wing went on to perform a similar low level raid, Operation Carthage, destroying Gestapo Headquarters in Copenhagen on 21 March 1945.[47]

The 1969 motion picture Mosquito Squadron is partially based on the Operation Jericho raid.[48]

References

- Notes

- William Sugden, a flight commander in 464 Squadron wrote later, "Anyone meeting Charles Pickard for the first time, as I did in July 1943, could hardly fail to be impressed, very tall, 6 feet 3-inch, blond, debonair, with an easy-going casual manner, plus three DSOs, a DFC, etc, a distinctive loping walk and invariably accompanied by his Old English sheep-dog, Ming. Most of us knew him by name since he had starred in the film "Target for Tonight", flying a Wellington, 'F for Freddie'. We had heard about some of his 'cloak and dagger' operations, flown to the Continent from RAF Tempsford, dropping and picking up agents by moonlight in Lysanders and the longer-range missions in Hudsons; we were familiar, too, with his ditching in the North Sea and the dropping of paratroops at Bruneval. We knew he would not be a chairborne CO, not many were in 2 Group as Embry insisted on almost everyone seeing a bit of the war, even the doctors and padres were encouraged to have a go![37]

- Taken from Mosquito SB-F (F-Feddie, W/Cdr Bob Iredale and F/Lt J. L. McCaul). The aircraft following is MM402 SB-A (A-Apple, S/Ldr W. R. C. Sugden and F/O A. N. Bridges).[40]

- Citations

- "Group Captain P C Pickard, DSO and two bars, DFC and Flight Lieutenant J A Broadley, DSO, DFC, DFM". Imperial War Museum.

- "Raid on Amiens Prison – The Myth of the Mosquito". 25 June 2017.

- "Deaths". The Times (Issue 49962, col D). 22 September 1944. p. 7.

- "Edward Hardwicke obituary". The Guardian. 18 May 2011.

- Orchard, Adrian (February 2006). "Group Captain Percy Charles "Pick" Pickard DSO**, DFC 1915–1944" (PDF). Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- "Pickard, Percy Charles - TracesOfWar.com". www.tracesofwar.com.

- "No. 34369". The London Gazette. 9 February 1937. p. 895.

- "No. 34457". The London Gazette. 23 November 1937. p. 7352.

- Bowyer 2001, p. 143.

- http://www.rafcommands.com/database/wardead/details.php?qnum=35925

- "Brave Percy was the wartime Pick of the RAF bunch". www.chichester.co.uk.

- Jonathan F Vance (2000). A Gallant Company. Pacifica Military. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-935-55347-5.

- Otter 2013, p. 253.

- "311 Sqn Never Regard Their Numbers – Bomber Command". 30 July 2015.

- "Pickard, Percy Charles". Traces of War.

- "BFI Screenonline: Target for Tonight (1941)". www.screenonline.org.uk.

- Ashcroft 2013.

- "Operation Biting: The Bruneval Raid". SOFREP. 8 September 2013.

- "Operation Biting – The Intelligence Gathering Radar Raid at Bruneval, France." www.combinedops.com.

- Ashcroft, Michael (13 September 2012). Heroes of the Skies. Headline. ISBN 9780755363919 – via Google Books.

- "No. 35954". The London Gazette (Supplement). 23 March 1943. p. 1413.

- "Charles Pickard (1915–1944)". www.chrishobbs.com.

- Verity (2002), various

- "161 Sqdn Sorties Feb/Mar 44". 14 August 2015.

- "Claims to Fame – Aviation Aces". www.hatfield-herts.co.uk.

- Helm, p 33

- Coxon, David (19 May 2016). "Brave Percy was the wartime Pick of the RAF bunch". Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- Bowman, Martin W. (2016). The Bedford Triangle: Undercover Operations from England in World War II. Skyhorse. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-5107-0868-6.

- K. R. M. Short, ‘Pickard, Percy Charles (1915–1944)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edition, May 2008, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/62384. Retrieved on 5 November 2008 Archived 13 February 2011 at WebCite

- "Obituary: Flt Lt Geoffrey Osborn". The Telegraph. 1 August 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- Gibson 2019, p. 307.

- Heroes of the Skies Michael Ashcroft

- "CHAPTER 6 – Daylight Raids by the Light Bombers | NZETC". nzetc.victoria.ac.nz.

- http://www.dambusters.org.uk/war-personalities/leaders/geoffrey-leonard-cheshire/

- Bateman 2009, pp. 61–63.

- Saunders 1975, p. 91.

- Bowman 2012, p. 218.

- Shores & Thomas 2004, p. 73.

- "Operation Jericho: Mosquito Raid on Amiens Prison". 12 January 2017.

- Bowyer 2004, p. 113.

- Bowyer 2001, p. 149.

- Budanovic, Nikola (22 February 2018). "Operation Jericho: A Rescue Mission Which Turned into A Bloodbath". War History Online. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- Casualty details—Pickard, Percy Charles, Casualty details—Broadley, John Alan, Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved on 5 November 2008. Archived 13 February 2011 at WebCite

- 'Operation Jericho', BBC (TV), 20 October 2011

- "Wingleader Magazine – Issue 2". Issuu.

- "Bid to honour British flying ace". The Connexion. 27 February 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- "RAF – Attack on Gestapo Headquarters". 1 January 2018. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018.

- "Operation Jericho: Heroic RAF Pilots Used Mosquitos to Bust German Prison Camps in WWII". AVGeekery.Com. 18 February 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- Bibliography

- Bateman, Alex No 617 'Dambuster' Sqn Oxford : Osprey, (2009).

- Bowyer, Chaz Bomber Barons Barnsley : Cooper, (2001).

- Gibson, Guy Enemy coast ahead : the illustrated memoir of Dambuster Guy Gibson Barnsley, S. Yorkshire : Greenhill Books, (2019).

- Otter, Patrick 1 Group: Swift to Attack: Bomber Command's Unsung Heroes Barnsley, South Yorkshire : Pen & Sword Aviation, (2013).

- Shores, Christopher F and Chris Thomas 2nd Tactical Air Force Hersham, Surrey (2004).

- Verity, Hugh We Landed by Moonlight Shepperton, Surrey: Ian Allan Limited (1978).

Further reading

- Bourne, Merfyn The Second World War in the air : the story of air combat in every theatre of World War Two Leicester: Matador, (2013).

- Bowyer, Chaz Mosquito at war London: Allan (1979). ISBN 978-0-7110-0474-0

- Hamilton, Alexander Wings of Night : Secret Missions of Group Captain Pickard, DSO and Two Bars, DFC Crecy Bks., (1977). ISBN 978-0-7183-0415-7

- Harclerode, Peter Wings of War – Airborne Warfare 1918–1945 Weidenfeld & Nicolson (2005). ISBN 0-304-36730-3

- McCairns, James Lysander Pilot (2015).

- O'Connor, Bernard RAF Tempsford : Churchill's most secret airfield Stroud: Amberley (2010).

- Oliver, David Airborne Espionage Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing Limited (2005).

- Orchard, Adrian Group Captain Percy Charles "Pick" Pickard DSO**, DFC 1915–1944 February 2006

- Otway, T.B.H The Second World War 1939–1945 Army — Airborne Forces Imperial War Museum, (1990). ISBN 0-901627-57-7

- Ward, Chris and Steve Smith 3 Group Bomber Command: an operational record Barnsley : Pen & Sword Aviation (2008).

- Williams, Ray Armstrong Whitworth's Night Bomber Aeroplane Monthly, October 1982.