Pharyngeal jaw

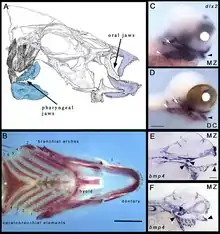

Pharyngeal jaws are a "second set" of jaws contained within an animal's throat, or pharynx, distinct from the primary or oral jaws. They are believed to have originated as modified gill arches, in much the same way as oral jaws. Originally hypothesized to have evolved only once,[1] current morphological and genetic analyses suggest at least two separate points of origin.[2][3] Based on connections between musculoskeletal morphology and dentition, diet has been proposed as a main driver of the evolution of the pharyngeal jaw.[4][5] A study conducted on cichlids showed that the pharyngeal jaws can undergo morphological changes in less than two years in response to their diet.[6] Fish that ate hard shelled prey had a robust jaw with molar-like teeth fit for crushing their durable prey. Fish that ate softer prey, on the other hand, exhibited a more slender jaw with thin, curved teeth used for tearing apart fleshy prey.[5] These rapid changes are an example of phenotypic plasticity, wherein environmental factors affect genetic expression responsible for pharyngeal jaw development.[6][7] Studies of the genetic pathways suggest that receptors in the jaw bone respond to the mechanical strain of biting hard-shelled prey, which prompts the formation of a more robust set of pharyngeal jaws.[7]

Cichlids

A notable example are fish from the family Cichlidae. Cichlid pharyngeal jaws have become very specialized in prey processing and may have helped cichlid fishes become one of the most diverse families of vertebrates.[8] However, later studies based on Lake Victoria cichlids suggest that this trait may also become a handicap when competing with other predator species.[9]

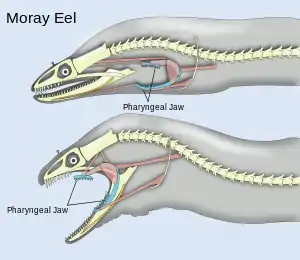

Moray eels

Most fish species with pharyngeal teeth do not have extendable pharyngeal jaws. A particularly notable exception is the highly mobile pharyngeal jaw of the moray eels. These are possibly a response to their inability to swallow as other fishes do by creating a negative pressure in the mouth, perhaps induced by their restricted environmental niche (burrows). Instead, when the moray bites prey, it first bites normally with its oral jaws, capturing the prey. Immediately thereafter, the pharyngeal jaws are brought forward and bite down on the prey to grip it; they then retract, pulling the prey down the moray eel's gullet, allowing it to be swallowed.[10]

Popular culture

The exceptional mobility of the moray eel's pharyngeal jaws was discovered in 2007 by UC Davis scientists. Almost three decades before (1979), the fictional xenomorph creature from Alien series was first depicted showing a second set of jaws for attacking its prey. However, at that time pharyngeal jaws in other fishes were already known.[11]

References

- Harvard University.; University, Harvard (1981–1986). Breviora. no.464-487 (1981-1986). Cambridge, Mass.: Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University.

- Mabuchi, Kohji; Miya, Masaki; Azuma, Yoichiro; Nishida, Mutsumi (2007). "Independent evolution of the specialized pharyngeal jaw apparatus in cichlid and labrid fishes". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-10. PMC 1797158. PMID 17263894.

- Wainwright, Peter C.; Smith, W. Leo; Price, Samantha A.; Tang, Kevin L.; Sparks, John S.; Ferry, Lara A.; Kuhn, Kristen L.; Eytan, Ron I.; Near, Thomas J. (2012). "The Evolution of Pharyngognathy: A Phylogenetic and Functional Appraisal of the Pharyngeal Jaw Key Innovation in Labroid Fishes and Beyond". Systematic Biology. 61 (6): 1001–1027. doi:10.1093/sysbio/sys060. ISSN 1063-5157. JSTOR 41677996. PMID 22744773.

- Grubich, Justin (2003). "Morphological convergence of pharyngeal jaw structure in durophagous perciform fish". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 80 (1): 147–165. doi:10.1046/j.1095-8312.2003.00231.x. ISSN 1095-8312.

- Aguilar-Medrano, Rosalía (January 2017). "Ecomorphology and evolution of the pharyngeal apparatus of benthic damselfishes (Pomacentridae, subfamily Stegastinae)". Marine Biology. 164 (1): 21. doi:10.1007/s00227-016-3051-3. ISSN 0025-3162. S2CID 90985865.

- Gunter, Helen M.; Fan, Shaohua; Xiong, Fan; Franchini, Paolo; Fruciano, Carmelo; Meyer, Axel (2013-08-19). "Shaping development through mechanical strain: the transcriptional basis of diet-induced phenotypic plasticity in a cichlid fish". Molecular Ecology. 22 (17): 4516–4531. doi:10.1111/mec.12417. ISSN 0962-1083. PMID 23952004. S2CID 17490095.

- Schneider, Ralf F.; Li, Yuanhao; Meyer, Axel; Gunter, Helen M. (2014-07-30). "Regulatory gene networks that shape the development of adaptive phenotypic plasticity in a cichlid fish". Molecular Ecology. 23 (18): 4511–4526. doi:10.1111/mec.12851. ISSN 0962-1083. PMID 25041245. S2CID 8021527.

- Hulsey, C.D.; Garcia de Leon, F.J.; Rodiles-Hernandez, R. (2006). "Micro- and macroevolutionary decoupling of cichlid jaws: A test of Liem's key innovation hypothesis". Evolution. 60 (10): 2096–2109. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb01847.x. PMID 17133866. S2CID 22638283.

- McGee, Matthew D.; Borstein, Samuel R.; Neches, Russell Y.; Buescher, Heinz H.; Seehausen, Ole; Wainwright, Peter C. (27 November 2015). "A pharyngeal jaw evolutionary innovation facilitated extinction in Lake Victoria cichlids". Science. 350 (6264): 1077–1079. Bibcode:2015Sci...350.1077M. doi:10.1126/science.aab0800. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 26612951.

- Mehta, Rita S.; Wainwright, Peter C. (6 September 2007). "Raptorial jaws in the throat help moray eels swallow large prey". Nature. 449 (7158): 79–82. Bibcode:2007Natur.449...79M. doi:10.1038/nature06062. PMID 17805293. S2CID 4384411.

- Zimmer, Carl (11 September 2007). "If the First Bite Doesn't Do It, the Second One Will". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

External links

- "'Alien' Jaws Help Moray Eels Feed". UC Davis. 2007-09-05.

- "article explaining moray eel pharyngeal jaws". National Science Foundation.

- "Video of a moray eel eating".