Phase resetting in neurons

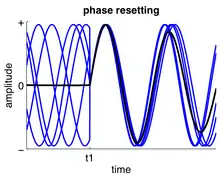

Phase resetting in neurons is a behavior observed in different biological oscillators and plays a role in creating neural synchronization as well as different processes within the body. Phase resetting in neurons is when the dynamical behavior of an oscillation is shifted. This occurs when a stimulus perturbs the phase within an oscillatory cycle and a change in period occurs. The periods of these oscillations can vary depending on the biological system, with examples such as: (1) neural responses can change within a millisecond to quickly relay information; (2) In cardiac and respiratory changes that occur throughout the day, could be within seconds; (3) circadian rhythms may vary throughout a series of days; (4) rhythms such as hibernation may have periods that are measured in years.[1][2] This activity pattern of neurons is a phenomenon seen in various neural circuits throughout the body and is seen in single neuron models and within clusters of neurons. Many of these models utilize phase response (resetting) curves where the oscillation of a neuron is perturbed and the effect the perturbation has on the phase cycle of a neuron is measured.[3][4]

History

Leon Glass and Michael Mackey (1988) developed the theory behind limit cycle oscillators to observe the effects of perturbing oscillating neurons under the assumption the stimulus applied only affected the phase cycle and not the amplitude of response.[5]

Phase resetting plays a role in promoting neural synchrony in various pathways in the brain, from regulating circadian rhythms and heartbeat via cardiac pacemaker cells to playing significant roles in memory, pancreatic cells and neurodegenerative diseases such as epilepsy.[6][7] Burst of activity in patterns of behaviors occur through coupled oscillators using pulsatile signals, better known as pulse-coupled oscillators.[8][9]

Methodology of study

Phase response curve

Shifts in phase (or behavior of neurons) caused due to a perturbation (an external stimulus) can be quantified within a Phase Response Curve (PRC) to predict synchrony in coupled and oscillating neurons.[8][3] These effects can be computed, in the case of advances or delays to responses, to observe the changes in the oscillatory behavior of neurons, pending on when a stimulus was applied in the phase cycle of an oscillating neuron. The key to understanding this is in the behavioral patterns of neurons and the routes neural information travels. Neural circuits are able to communicate efficiently and effectively within milliseconds of experiencing a stimulus and lead to the spread of information throughout the neural network.[10] The study of neuron synchrony could provide information on the differences that occur in neural states such as normal and diseased states. Neurons that are involved significantly in diseases such as Alzheimer's disease or Parkinson's disease are shown to undergo phase resetting before launching into phase locking where clusters of neurons are able to begin firing rapidly to communicate information quickly.[8][10]

A phase response curve can be calculated by noting changes to its period over time depending on where in the cycle the input is applied. The perturbation left by the stimulus moves the stable cycle within the oscillation followed by a return to the stable cycle limit. The curve tracks the amount of advancement or delay due to the input in the oscillating neuron. The PRC assumes certain patterns of behavior in firing pattern as well as the network of oscillating neurons to model the oscillations. Currently, only a few circuits exist which can be modeled using an assumed firing pattern.[5]

In order to model the behavior of firing neural circuits, the following is calculated to generate a PRC curve and its trajectory. The period is defined as the unperturbed period of an oscillator from the phase cycle defined as 0≤ ∅ ≤1 and the cycle that has undergone a perturbation is known as as shown in the following equation.[3] An advance in phase occurs when trajectory of the motion is displaced in the direction of the motion due a shortening of period whereas a phase delay occurs when the displacement occurs in the opposite direction of motion.

Types of phase response curves

If the perturbation to the oscillatory cycle is infinitesimally small, it is possible to derive a response function of the neural oscillator. This response function can be classified into different classes (Type 1 and Type 2) based upon its response.[8][3][11][12]

- Type I Phase Response Curves are non-negative and strictly positive thus perturbations are only able to enhance a spike in phase, but never delay it. This occurs through a slight depolarization, such as postsynaptic potentials that increase the excitation of an axon. Type I PRCs are also shown to fire more slowly towards the onset of firing. Examples of Models that exhibit Type I PRCs in weakly coupled neural oscillators include the Connor and the Morris–Lecar model.[3][11][13]

- Type II Phase Response Curves can have negative and positive regions. Due to this characteristic, Type II PRCs are able to advance or delay changes in phase pending on the timing of perturbation that occurs. These curves can also have abrupt onset of firing and due to this, are unable to fire below their threshold. An example of a Type II PRC is seen within the Hodgkin–Huxley model.[3][11]

Assumptions of phase response curves

Numerous research has suggested two primary assumptions that allow the use of PRCs to be used to predict the occurrence of synchrony within neural oscillation. These assumptions work to show synchrony within coupled neurons that are linked to other neurons. The first assumption claims that coupling between neurons must be weak and requires an infinitesimally small phase change in response to a perturbation.[8][3][14]

The second assumption assumes coupling between neurons to be pulsatile where the perturbation to calculate PRC should only include those inputs that are received within the circuit. This leads to a limitation of each phase being completed within a reset before another perturbation can be received.[8][14]

The main difference between the two assumptions is for pulsatile the effects of any inputs must be known or measured prior. In weak coupling, only the magnitude of response due to a perturbation needs to be measured to calculate phase resetting. The weak coupling also induces the claim that many cycles must occur prior to convergence of oscillators to phase lock to lead to synchronization.[8][14]

Conditions for validity of phase response curve

Much argument still exists in whether the assumptions behind phase resetting are valid for analysis of neural activity leading to synchronization and other neural properties. Event-related Potential (ERP) is a commonly used measure to the response of the brain to different events and can be measured via electroencephalography (EEG). EEGs can be used to measured electrical activity throughout the brain noninvasively.[14] The Phase Response Curve operates under the following criteria and must occur to prove that phase resetting is the cause of the behavior:

- An oscillation must already be occurring before it can reset in its phase. This implies that resetting in response to a stimulus can only occur if the oscillation pre-existed before the reset.

- If due to resetting of oscillation leads to the formation of ERP, the ERP must show similar characteristics.

- The neural sources responsible for the generation of the ERP must be the same as ongoing oscillation to be considered phase resetting.[14]

Arguments for and against phase resetting model

Arguments that claim the activity pattern observed in neurons is not phase resetting, but could instead be the response to evoked potentials (ERPs), include:

- If the ERP was generated due to phase resetting, measuring the phase concentration alone is not enough to prove that phase resetting is occurring. An example of this is measuring while filtering data as this may actually induce an artificial oscillation in response to perturbation. It has been suggested that this argument may be overcome if there is no increase in power of the phase reset from pre-stimulus to post-stimulus.[14]

- The amplitude and phase of ongoing oscillations at the time a stimulus is applied should influence the ERP once generated by current oscillations. This argument is overcome if the amplitude or phase of current oscillations is affected and creates an ERP, and cannot be assumed to be an independent event.[14]

Biological occurrences

Epilepsy

Epilepsy is traditionally viewed as a disease resulting from hypersynchronous neural activity. Research has shown that specific changes in the topology of neural networks and their increase in synaptic strength can move into hyper-excited states. Normal networks of neurons fire in synchronous patterns that lead to communication; if this behavior is excited further, it can lead to "bursting" and significantly increase this communication. This increase then leads to over-activation of neural networks and finally to seizures. Diseases such as epilepsy demonstrate how synchrony amongst neural networks must be highly regulated to prevent asynchronous activity. The study of neural regulation could help to outline methods to reduce symptoms of asynchronous activity such as that observed in epilepsy.[15][16]

Memory

Phase resetting is important in the formation of long-term memories. Due to synchronization within the gamma-frequency range has been shown to be followed by phase resetting of theta oscillations when phase-locked by a stimulus. This shows increased neural synchrony, due to connections within neural networks, during the formation of memories by reactivating certain networks continuously.[17][18]

During memory tasks that required quick formation of memories, phase resetting within alpha activity increased the strength of the memories.[14][19]

Hippocampus

Theta phase precession is a phenomenon observed in the hippocampus of rats and relates to the timing of neural spikes.[20][21] When rats navigate around their environment, there are certain neurons in the hippocampus that fire (spike) when the animal is near a familiar landmark. Each neuron is tuned to a particular unique landmark, and for that reason, these neurons are called place cells.

Curiously, it turns out that when a place cell fires is determined by how far the animal is from the landmark. There is a background oscillation in the hippocampus in the theta band (4 – 8 Hz). As the animal approaches the landmark, the spiking of the place cell moves earlier in phase relative to the background theta oscillation, so that the phase offset essentially measures or represents the distance. This phase shifting relative to spatial distance is called phase precession.[22]

See also

References

- Krogh-Madsen, Trine, et al. "Phase Resetting Neural Oscillators: Topological Theory Versus the RealWorld." Phase response curves in neuroscience. Springer New York, 2012. 33-51.

- Czeisler, C. A.; RE Kronauer; JS Allan; JF Duffy; ME Jewett; EN Brown; JM Ronda (16 June 1989). "Bright light induction of strong (type 0) resetting of the human circadian pacemaker". Science. 244 (4910): 1328–1333. doi:10.1126/science.2734611. PMID 2734611.

- Canavier, Carmen C. (2006). "Phase Response Curve". Scholarpedia. 1 (12): 1332. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.1332.

- Achuthan, S.; Carmen Canavier (22 April 2009). "Phase-Resetting Curves Determine Synchronization, Phase Locking, and Clustering in Networks of Neural Oscillators". The Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (16): 5218–5233. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0426-09.2009. PMC 2765798. PMID 19386918.

- Glass, L.; Michael C. Mackey (1988). From Clocks to Chaos: The Rhythms of Life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691084961.

- Kuramoto, Yoshiki (1984). Chemical oscillations, waves, and turbulence. Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0387133225.

- Winfree, Arthur T (1967). "Biological rhythms and the behavior of populations of coupled oscillators". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 16 (1): 15–42. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(67)90051-3. PMID 6035757.

- Canavier, Carmen; S. Achuthan (2010). "Pulse coupled oscillators and the phase resetting curve". Mathematical Bioscences. 226 (2): 77–96. doi:10.1016/j.mbs.2010.05.001. PMC 3022482. PMID 20460132.

- Rohling, Jos H. T; Vanderleest H; Michel S; Vansteensel M; Meijer J. (2011). "Phase Resetting of the Mammalian Circadian Clock Relies on a Rapid Shift of a Small Population of Pacemaker Neurons". PLoS ONE. 6 (9): 1–9. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025437. PMC 3178639. PMID 21966529.

- Varela, F; J. Lachaux; E. Rodriguez; J.Martinierie (2001). "The brainweb: Phase synchronization and large-scale integration". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2 (4): 229–239. doi:10.1038/35067550. PMID 11283746.

- Ermentout, B. (1996). "Type I membranes, phase resetting curves, and synchrony". Neural Computation. 5. 8 (5): 979–1001. doi:10.1162/neco.1996.8.5.979. PMID 8697231.

- Hansel, D.; Mato, G.; Meunier, C. (March 1995). "Synchrony in excitatory neural networks". Neural Computation. 7 (2): 307–337. doi:10.1162/neco.1995.7.2.307. PMID 8974733.

- Wang, S.G.; Musharoff M; Canavier C; Gasparini S (June 2013). "Hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons exhibit type 1 phase-response curves and type 1 excitability". Journal of Neurophysiology. 109 (11): 2757–2766. doi:10.1152/jn.00721.2012. PMC 3680797. PMID 23468392.

- Sauseng, P; Klimesch W; Gruber WR; Hanslmayr S; Freunberger R; Doppelmayr M (8 June 2007). "Are event-related potential components generated by phase resetting of brain oscillations? A critical discussion". Neuroscience. 146 (4): 1435–44. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.03.014. PMID 17459593.

- Neotoff, Theoden; Robert Clewley; Scott Arno; Tara Keck; John A. White (15 September 2004). "Epilepsy in Small-World Networks". The Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (37): 8075–8083. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.1509-04.2004. PMC 6729784. PMID 15371508.

- Jahangiri, A; Durand D. (April 2011). "Phase resetting analysis of high potassium epileptiform activity in CA3 region of the rat hippocampus". International Journal of Neural Systems. 21 (2): 127–138. doi:10.1142/S0129065711002705. PMID 21442776.

- Axmacher, Nikolai; Florian Mormann; Guillen Fernández; Christian E. Elger; Juergen Fell (24 January 2006). "Memory formation by Neural Synchronization". Brain Research Reviews. 52 (1): 170–182. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.01.007. PMID 16545463.

- Jutras, Michael; Elizabeth A. Buffalo (18 March 2010). "Synchronous Neural Activity and Memory formation". Neurobiology. 20 (2): 150–155. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2010.02.006. PMC 2862842. PMID 20303255.

- Yu, Shan; Debin Huang; Wolf Singer; Danko Nikolic (9 April 2008). "A Small world of Neural Synchrony". Cerebral Cortex. 18 (12): 2891–2901. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhn047. PMC 2583154. PMID 18400792.

- O'Keefe, John; Recce, Michael L. (1993). "Phase relationship between hippocampal place units and the EEG theta rhythm". Hippocampus. 3 (3): 317–330. doi:10.1002/hipo.450030307. PMID 8353611.

- Skaggs, William E.; et al. (1996). "Theta phase precession in hippocampal". Hippocampus. 6 (2): 149–172. doi:10.1002/(sici)1098-1063(1996)6:2<149::aid-hipo6>3.0.co;2-k. PMID 8797016.

- Jensen, Ole; Lisman, John E. (1996). "Hippocampal CA3 region predicts memory sequences: accounting for the phase precession of place cells". Learning & Memory. 3 (2–3): 279–287. doi:10.1101/lm.3.2-3.279. PMID 10456097.