Planet Comics

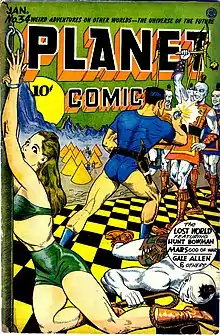

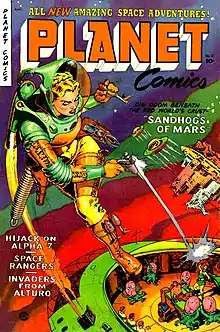

Planet Comics was a science fiction comic book title published by Fiction House from January 1940 to Winter 1953. It was the first comic book dedicated wholly to science fiction.[1] Like most of Fiction House's early comics titles, Planet Comics was a spinoff of a pulp magazine, in this case Planet Stories. Like the magazine before it, Planet Comics features space operatic tales of muscular, heroic space adventurers who are quick with their "ray pistols" and always running into gorgeous women who need rescuing from bug-eyed space aliens or fiendish interstellar bad guys.

| Planet Comics | |

|---|---|

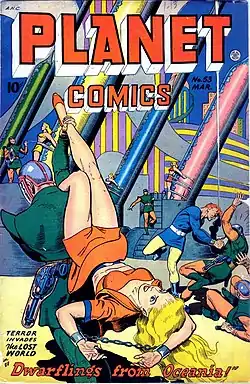

Cover to Planet Comics #53 (March 1948). Art by Joe Olin. | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Fiction House |

| Format | Anthology |

| Publication date | January 1940 – Winter 1953 |

| No. of issues | 73 |

| Main character(s) | Flint Baker and the Space Rangers Gale Allen Mysta of the Moon Spurt Hammond et al. |

Publication history

Planet Comics #1 was released with a cover-date of January 1940, and ran for 73 issues until Winter 1953.[2] Initially produced on a monthly schedule, issue #8 (September 1940) saw it slip to a bimonthly title, which it held until the end of 1949. From issue #26 (September 1943), "Planet Comics was cut to 60 pages," resulting in the merging of two strips: Flint Baker and Reef Ryan.[3] Issue #63 (Winter 1949) began a quarterly release schedule, but #64, #65, and #66 were ultimately released annually, dated Spring 1950, 1951, and 1952, respectively. Issue #67 (Summer 1952) got the comic back on its quarterly release schedule, but the title only lasted a further seven issues, with its last (#73) again delayed for over a year, following issue #72 (Fall 1953).[2]

Style and Themes

Planet Comics was the foremost purveyor of good girl art in comic books of the period, and is considered highly collectible by modern fans of comics' Golden Age. It specialized in colorful and lurid stories of interstellar action, ingenuous and attractive heroes and heroines, breezy dialogue, and the “barest smattering of sense and substance” (Benton 1992, p. 27). Its covers usually featured a beautiful, scantily-attired spacewoman with long bare legs being menaced by a frightful alien monster, while a sleek, heroic spaceman comes to her rescue.

Sometimes, though, Planet Comics reversed this formula: both covers and stories occasionally provided heroines who handily defeated the space aliens and interplanetary villains with little or no assistance from males (the comic was also seen as a fantasy title). Cynics might have noted that this sex-equality strategy in effect simply multiplied the number of lovely girls shown per panel, and insured that each and every panel featured at least one smashing spacegirl.

Writers

The Flint Baker/Space Ranger stories, according to Raymond Miller, "featured such writers as Al Schmidt and Huxley Haldane."[3] Jerry Bails and Hames Ware's Who's Who of American Comic Books mentions Herman Bolstein and Dick Briefer.[4]

Bails and Ware also list writers including Walter B. Gibson[5] (The Shadow) and Frank Belknap Long,[6] as working on "various features" for Planet Comics throughout the 1940s.

Artists

The strong female heroines of Planet Comics were complemented by Fiction House's employing several female artists to work on such tales, particularly Lily Renée, Marcia Snyder, Ruth Atkinson, and Fran(ces) Hopper (née Dietrick), whose art for "Mysta of the Moon" was often stunning. In addition, many artists who would become well-known names worked on Planet Comics stories over its 13-year history. These included the likes of Murphy Anderson, Matt Baker, Nick Cardy, Joe Doolin, Graham Ingels, George Evans, Ruben Moreira, John Cullen Murphy, George Tuska, and Maurice Whitman.

The early covers were drawn by industry legend Will Eisner.[7] Later covers were predominantly the work of two men — Dan Zolnerowich (later Dan Zolne) and Joe Doolin. Zolne is believed to have produced covers for issues #10-25 (January 1941 – July 1943), and Doolin is thought to have illustrated all-bar-three of #26-65 (September 1943 – Spring 1951).[2]

Reception and Influence

While young male readers were no doubt attracted to the pin-up quality of Planet Comics's artwork, letters from readers printed in the comic demonstrate that its readership also included girls, who were perhaps drawn to the array of competent and capable space heroines (Benton 1991, p. 31).

Planet Comics was considered by noted fan Raymond Miller to be "perhaps the best of the Fiction House group," as well as "most collected and most valued."[3] In Miller's opinion, it "wasn't really featuring good art or stories... in the first dozen or so issues," not gaining most of "its better known characters" until "about the 10th issue." "Only 3 of [its] long running strips started with the first issue... Flint Baker, Auro - Lord of Jupiter, and the Red Comet."[3]

The comics historian John Benton offers this summary: “Planet Comics was the epitome of breezy, sexy, mindless, action-filled science fiction. In many respects [it was] a throwback to the earlier science fiction magazines and simpler times.”.[1]

Characters and Features

- Flint Baker – One of the longest-running strips, Flint Baker was another athletic space hero, who became part of the Space Rangers.[8] Baker's debut story, "The One-Eyed Monster Men From Mars", was also the first story in Planet Comics #1, illustrated by Dick Briefer. Flint Baker was the "main hero" and "cover feature" of most of the first 13 issues, and after 25 issues he "team[ed] up with Reef Ryan to form the Space Rangers" when Planet Comics dropped its page count. Appearances between issues #2 and #60 (initially as "Flint Baker," later as "Space Rangers") were illustrated by a full range of artists, including Nick Viscardi, Joe Doolin and Artie Saff,[3] Arthur Peddy, Lee Elias, Frank Doyle, and Joe Cavallo.[2] The Space Rangers "were drawn by Lee Elias, Bob Lubbers," and others.[3]

- Auro, Lord of Jupiter – Two different characters of this name appeared in Planet Comics. The first incarnation was the son of Professor Hardwich, and appeared in most issues between #1-29. He was essentially an outer space version of Tarzan, where Auro was "befriended by a saber tooth tiger," stranded on Jupiter with "muscles... as strong as steel" thanks to the higher gravitational pull of the planet. The best artwork on the first series of Auro stories was, wrote Miller, "by Raphael Astarita,"[3] whose name Jerry Bails and Hames Ware spell "Rafael".[9] Auro's second incarnation started 11 issues after his first ended, in issue #41, when a young scientist named Chester Edson "crashes on Jupiter," and his "spirit is transferred into the body of [the original] Auro," who is thus resurrected as a Flash Gordon-esque hero.[3] Miller names Dick Charles as the main writer of both series; Bails and Ware list only Richard Case and Herman Bolstein.[4] Auro was illustrated by a number of different artists, among them Doolin, Graham Ingels, and Astarita.[2] Miller suggests that August Froelich drew the appearance in issue #41, and says that Ingels "was the last artist."[3]

- The Red Comet – A "costumed hero who fought crime all over the universe," the Comet sometimes "grew to giant-size, like the Spectre." The feature was written (according to Miller) by Cy Thatcher and appeared in issues #1, #3-20, and #37.[3] Accompanied by a "girl, Dolores, and a boy, Rusty," his adventures were illustrated for odd adventures by Rudy Palais and a host of artists, with only Alex Blum (#6-10) and Saul Rosen (#17-19) thought to have drawn more than two episodes.[2][3]

- The Lost World - The Red Comet was replaced by "The Lost World," which appeared in issues #21-69, as the lead feature (becoming one of the longest-running strips) featuring Hunt Bowman. The first episode was drawn by Palais, with Viscardi taking over for issue #22.[2][3] Set in the 33rd century, Bowman was a guerrilla-fighter (alongside Lyssa, Queen of the Lost World) against the reptilian Voltamen, conquerors of Earth. (Miller notes that "[i]n #24 Hunt and Lyssa returned to Earth... [and] never returned to the Lost World.") In issue #36, the duo were joined by "3 more Earth people," named Bruce, Robin, and Bonnie.[3] Later episodes were drawn by Ingels (c. #24-31), Lily Renée (#32-49), and George Evans (#50-64).[2][3]

- Reef Ryan – A heroic space captain, "[not] much different from... Flint Baker," Ryan also became part of the Space Rangers, after appearing solo in issues #13-25. Miller names the writer of Reef Ryan (and then Space Rangers) as "Hugh Fitzhugh". Ryan was soon dropped from the newly named strip, however, in favor of a boy named Hero (issue #42).[3] Initially drawn by Al Gabriele, later issues featured inks by George Tuska.[2]

- The Space Rangers – From issue #26, with Planet Comics' page count dropped, "instead of dropping any characters, the Ryan and Baker strips were combined to form the Space Rangers."[3] The Space Rangers' uniforms were echoed by those seen on TV's Rocky Jones Space Ranger (1954).

- Gale Allen – A voluptuous female space adventurer in the far-off year of 1990, who led an all-female Woman's Space Battalion to fight menaces like the Mad Master of Venus, and her arch-enemy Prince Blaga Daru.[10] Gale appeared in almost every issue between #4 and #42.[3] Written by Douglas McKee, Gale's tales were illustrated by Bob Powell in issues #4-10 and Fran Deitrick/Hopper in #28-40.[2] In or around issue #34, the squadron were dropped.[3]

- Futura – Gale's replacement feature was, according to Miller, "a good series with fine art," a smashingly lovely crusader for interplanetary justice, and she appeared in issues #43-64.[3] The first six issues were drawn by Astarita in the style of Mac Raboy, while Joseph Cavallo is thought to have inked/drawn many of the later issues.[2] Futura began "with a scantily-clad girl... abducted by her invisible pursuer" and taken to "the city of Cymradia in space." The strip was drawn in a manner similar to Prince Valiant, with "no word balloons in the panels."[3]

- Star Pirate – The "Robin Hood of the space lanes" looked very much like the DC Comics hero Starman, and appeared between issues #12 and #64. Among several artists, George Appel produced a dozen early issues, while the bulk of issues #33-51 were drawn by Murphy Anderson, whose additions transformed the Pirate into "an almost completely new strip."[3] Three late issues (#59-61) are credited to newspaper comic strip artist Leonard Starr.[2][3]

- Mars, God of War – Named by Miller as "one of the most famous" strips, the adventures of the ancient Roman God causing violent mischief on other planets appeared between issues #15 and #35.[2][3] They were credited to writer Ross Gallen, and all drawn by Doolin. The embodiment of evil, the spirit of Mars would "single out a man or woman who had evil in them," possess them, and run rampant until "the end of each story [when] good always triumphed."[3]

- Mysta of the Moon – In the "Mars" feature in Planet Comics #35, the god discovers "a young boy and girl" taken to the moon by one Dr. Kort, who has "placed all the culture and knowledge known to man into their brains." In the events that follow, Mars possesses the boy's robot, and is ultimately defeated by the girl, although the boy and his robot are killed. The girl was Mysta, a gorgeous female version of Captain Future with a robot sidekick, and she took over from "Mars" in title as well as spirit in issue #36.[3] Appearing in issues #36-52 and #55-62, after Doolin, the strip was most notably illustrated by Fran Hopper (#37-42, #48-49).[2][3]

- Norge Benson - Between issues #12-32, comedy relief was provided by Norge Benson, written by "Olaf Bjorn," whom Miller identifies as Kip Beales.[11] Benson was accompanied by a girl (Jolie), a white bear (Frosting), and a reindeer (Hatrack). Al Walker drew issues #12-22, with Renée, Jim Mooney, and Fran Hopper drawing later episodes.[3]

Other extra features included "Spurt Hammond", human defender of the Planet Venus, who appeared c. issues #1-12[2] (or #8-13[3]), created and drawn by Henry Kiefer.[2] "Captain Nelson Cole", later an officer in the Space Patrol, appeared in solo adventures c. issues #1-14[2] (or #8-14[3]) and was originated by Alex Blum. "Crash Barker" (also "P"arker) was one of several space heroes, drawn — and possibly written — by Charles Quinlan for issue #6[2] (or #8[3]), running until #16 by other artists.[2] Another space hero, "Buzz Crandall", also had adventures around this time, drawn by artists including Gene Fawcette.[2] "Cosmo Corrigan" and "Don Granval" also appeared in three to four issues around #8/9-11.[3]

Other less notable short-lived strips included "Quorak, Super Pirate", "Amazona the Mighty Woman", "Tiger Hart" (whose one adventure was drawn by Fletcher Hanks using the pseudonym "Carlson Merrick"), "Space Admiral Curry", and "Planet Payson".[2]

Further reading

- "Mysta of the Moon" in Divas, Dames & Daredevils: Lost Heroines of Golden Age Comics by Mike Madrid, Exterminating Angel Press (2013)

References

- Benton, Mike. Science Fiction Comics: The Illustrated History (Dallas, TX: Taylor Publishing Company, 1992), p.33

- Steele, Henry (1978). Fiction House - A Golden Age Index. Al Dellinges.

- Miller, Raymond (c. 1970/1971). Love, G.B (ed.). "Planet Comics". The Fandom Annual. SFCA (2): 118–121. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Bails, Jerry; Ware, Hames. Who's Who of American Comic Books. Retrieved 2009-05-16.

- Bails, Jerry; Ware, Hames. "Walter Gibson". Who's Who of American Comic Books. Retrieved 2009-05-16.

- Bails, Jerry; Ware, Hames. "Frank Belknap Long". Who's Who of American Comic Books. Retrieved 2009-05-16.

- Planet Comics at the Grand Comics Database. Retrieved 2009-05-16.

- Nevins, Jess (2013). Encyclopedia of Golden Age Superheroes. High Rock Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-61318-023-5.

- Bails, Jerry; Ware, Hames. "Rafael Astarita". Who's Who of American Comic Books. Retrieved 2009-05-16.

- Nevins, Jess (2013). Encyclopedia of Golden Age Superheroes. High Rock Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-61318-023-5.

- Nevins, Jess (2013). Encyclopedia of Golden Age Superheroes. High Rock Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-61318-023-5.