Plutonium zwierleini

Plutonium zwierleini is one of the largest scolopendromorph centipedes in Europe, and one of the few potentially harmful to humans. Nevertheless, it has been rarely reported, only from the southern part of the Iberian and Italian peninsulas, Sardinia and Sicily.

| Plutonium zwierleini | |

|---|---|

| |

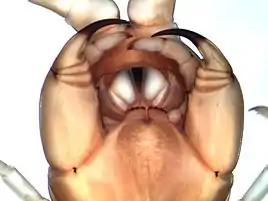

| P. zwierleini, from Montoro Superiore, Campania.

20 June 2014. Photo Valeria Balestrieri | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | Plutoniumidae |

| Genus: | Plutonium Cavanna, 1881 |

| Species: | P. zwierleini |

| Binomial name | |

| Plutonium zwierleini Cavanna, 1881 | |

Morphology

The body is mainly brown-orange, slightly darker on the head and the most posterior part of the body, including the ultimate pair of appendages. Conversely, the antennae and the walking legs are paler. The body length may surpasses 12 cm, which is the maximum measured from the anterior margin of the head to the posterior tip of the trunk, among the few specimens collected.[1] Even higher measures have been reported in the past.[2]

P. zwierleini is fully blind, without trace of eyes. As in all other centipedes, the first appendages of the trunk are a pair of piercing fangs, which are used to grasp and poison prey. Two denticulate plates project forwards between the fangs, which have also a small tubercle on their mesal side.

A total of 20 walking legs are present on both sides of the body. In addition to short setae that are sparse on the entire body surface, including the appendages, the ventral side of the basal articles of the legs are covered with remarkably dense and long setae, which is unusual among centipedes.[1] The function of these unusual setae is unknown. The tergites covering the body trunk, one every pair of legs, are alternatively slightly longer and slightly shorter, as common in scolopendromorph centipedes.[3]

The most posterior tergites are particularly broader and more sclerotized, and the last one is conspicuously elongate. A longitudinal series of 19 spiracles is present on each side of the body, one spiracle per walking leg, close to the leg attachment, to the exclusion of the first pair of legs. Such arrangement of the spiracles is unique to P. zwierleini in comparison to all other scolopendromorphs.[3] The ultimate pair of appendages resembles the anterior fangs in size, shape and mechanics: they are basally very swollen and bear elongate blade-edged claws. During locomotion, the ultimate appendages are kept aligned longitudinally at the end of the body. However, after disturbance, they are often raised and splayed, apparently assuming a warning posture.[1] The ultimate appendages are possibly employed in defence against predators and it has also been speculated that they could be used to catch and hold prey, but observations are lacking.

Juveniles are similar to adults, and there no significant differences between males and females. The few specimens found insofar are quite variable in the elongation of the antennae and the walking legs, but it is unclear whether this is associated with habitat differences or some geographic differentiation.[1]

Distribution and habitat

P. zwierleini was first described upon specimens collected around year 1878 near Taormina, in Sicily.[4] Soon after, the species was reported also from Sardinia and near Sorrento in the Italian peninsula. However, despite the large size and the distinctive morphological characters, P. zwierleini has been found only rarely. Up to 2017, less than 50 records have been documented.[1] Dedicated field campaigns carried on by different zoologists turned out often unsuccessful, while most records have been obtained by occasional findings by speleologists, amateurs and common citizens.

As far as known, P. zwierleini lives in four separate areas of southern Europe: in the southern Iberian Peninsula, between Malaga and Granada; in Sardinia, mainly in the eastern part; in some Tyrrhenian coastal areas of the southern part of the Italian peninsula, especially the Sorrento peninsula; and in Sicily, mainly in the north-eastern part.[1]

Specimens of P. zwierleini have been found both in epigeic habitats (rocky debris, woods, maquis, pastures and also urban settlements and cultivated land) and in hypogeic sites (in natural caves, at least in the Iberian peninsula and in Sardinia, but also inside buildings, especially basements and ground floors). All records have been between a few tens of metres above sea level to 1220 m, in Sardinia.

Evolutionary relationships

Both morphological and molecular analyses suggest that P. zwierleini belongs to the so-called “blind clade” of scolopendromorph centipedes (including Plutoniumidae, Cryptopidae and Scolopocryptopidae) and is strictly related to Theatops.[5][6][1] In the past, the evolutionary affinities of Plutonium have been a matter of speculations, within the more general debates on the evolution of the segmental anatomy of the Arthropoda.[7]

References

- Bonato L., Orlando M., Zapparoli M., Fusco G., Bortolin F. (2017). "New insights into Plutonium, one of the largest and least known European centipedes (Chilopoda): distribution, evolution and morphology". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlw026.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Attems, C. (1930). Myriopoda. 2. Scolopendromorpha. Das Tierreich 54. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Minelli, A. (2011). Treatise on Zoology - Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology. The Myriapoda. Volume 1. Leiden: Brill.

- Cavanna, G. (1881). "Nuovo genere (Plutonium) e nuova specie (P. zwierleini) di Scolopendridi". Bullettino della Società Entomologica Italiana. 13: 169–178.

- Shelley, R. M. (2002). A synopsis of the North American centipedes of the order Scolopendromorpha (Chilopoda). Virginia Museum of Natural History. ISBN 9781884549182.

- Vahtera V, Edgecombe GD, Giribet G (2012). "Evolution of blindness in scolopendromorph centipedes (Chilopoda: Scolopendromorpha): insights from an expanded sampling of molecular data". Cladistics. 38: 4–20. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2011.00361.x.

- Minelli A, Boxshall G, Fusco G (2013). Arthropod biology and evolution. Molecules, development, morphology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Verlag.