Principle of univariance

The principle of univariance states that one and the same visual receptor cell can be excited by different combinations of wavelength and intensity, so that the brain cannot know the color of a certain point of the retinal image. One individual photoreceptor type can therefore not differentiate between a change in wavelength and a change in intensity. Thus the wavelength information can be extracted only by comparing the responses across different types of receptors. The principle of univariance was first described by W. A. H. Rushton (p. 4P). [1]

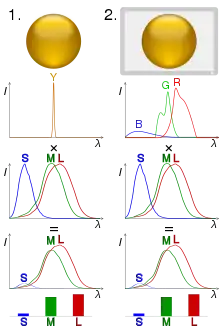

In column 1, a ball is illuminated by monochromatic light. Multiplying the spectrum by the cones' spectral sensitivity curves gives the response for each cone type.

In column 2, metamerism is used to simulate the scene with blue, green and red LEDs, giving a similar response.

Both cone monochromats (those who only have 1 cone type) and rod monochromats (those with no cones) suffer from the principle of univariance.The principle of univariance can be seen in situations where a stimulus can vary in two dimensions, but a cell's response can vary in one. For example, a coloured light may vary in both wavelength and in luminance. However, the brain's cells can only vary in the rate at which action potentials are fired. Therefore, a cell tuned to red light may respond the same to a dim red light as to a bright yellow light. To avoid this, the response of multiple cells is compared.

References

- W. A. H. Rushton (1972). "Pigments and signals in colour vision". Journal of Physiology. 220 (3): 1–31P. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009719. PMC 1331666. PMID 4336741.