Pristina

Pristina[1] (UK: /ˈpriːʃtɪnə, prɪʃˈtiːnə/,[2][3] US: /ˈprɪʃtɪnə, -nɑː/,[4] Albanian pronunciation: [pɾiʃˈtinə] (![]() listen); Albanian: Prishtina or Prishtinë, Serbian: Приштина / Priština) is the capital of Kosovo[lower-alpha 1] and the seat of the eponymous municipality and district. Its population is predominantly Albanian-speaking constituting the second-largest such city in Europe, after Tirana.[5][6] The city is located in the northeastern section of Kosovo in a relatively flat plain close to the Gollak mountains.

listen); Albanian: Prishtina or Prishtinë, Serbian: Приштина / Priština) is the capital of Kosovo[lower-alpha 1] and the seat of the eponymous municipality and district. Its population is predominantly Albanian-speaking constituting the second-largest such city in Europe, after Tirana.[5][6] The city is located in the northeastern section of Kosovo in a relatively flat plain close to the Gollak mountains.

Pristina

| |

|---|---|

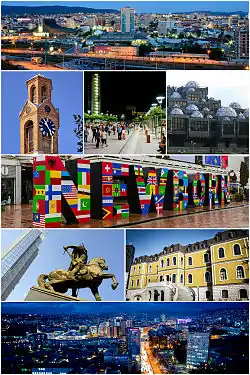

Photomontage of Pristina | |

Flag  Seal | |

Pristina  Pristina  Pristina | |

| Coordinates: 42°39′48″N 21°9′44″E | |

| Country | |

| District | Pristina |

| Municipality | Pristina |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Shpend Ahmeti (PSD) |

| Area | |

| • City | 30.3 km2 (11.7 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 652 m (2,139 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • City | 145,149 |

| • Density | 4,800/km2 (12,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 198,897 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 10000 |

| Area code(s) | +383 (0)38 |

| Vehicle registration | 01 |

| Website | prishtinaonline.com |

During the Paleolithic Age, what is now the area of Pristina was involved by the Vinča culture. It was home to several Illyrian and Roman people at the classical times. King Bardyllis brought various tribes together in the area of Pristina in the 4th century BC, establishing the Dardanian Kingdom.[7][8][9] The heritage of the classical era is still evident in the city, represented by ancient city of Ulpiana, that was considered one of the most important Roman cities in the Balkan peninsula. Between the 5th and the 9th century the area was part of the Byzantine Empire. In the middle of the 9th century it was ceded to the First Bulgarian Empire. In the early 11th century it fell under Byzantine rule and was included into a new province called Bulgaria. Between the late 11th and middle of the 13th century it was ceded several times to the Second Bulgarian Empire.

In the late Middle Ages, Pristina was an important town in Medieval Serbia and also the royal estate of Stefan Milutin, Stefan Uroš III, Stefan Dušan, Stefan Uroš V and Vuk Branković.[10] Following the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans, Pristina became an important mining and trading center due to its strategic position near the rich mining town of Novo Brdo. The city was known for its trade fairs and items, such as goatskin and goat hair as well as gunpowder.[11] The first mosque in Pristina was built in the late 14th century while under Serbian rule.[12]

Pristina is the most important transportation junction of Kosovo, for air, rail, and roads. The city's international airport is the largest airport of the country and among the largest in the region. A range of expressways and motorways, such as the R 6 and R 7, radiate out the city and connect it to Albania and North Macedonia.

Pristina is as well as the most essential economic, financial, political and trade center of Kosovo mostly due to its significant location in the center of the country. It is the seat of power of the Government of Kosovo, the residences for work of the president and prime minister of Kosovo and the Parliament of Kosovo.

Etymology

The name of the city could be derived from Proto-Slavic dialectal word *pryščina, meaning "spring (of water)", which is also attested in the Moravian dialects of Czech; it is derived from the verb *pryskati, meaning "to splash" or "to spray" (prskati in modern Serbian).[13] The toponym Priština also appears as the name of a hamlet near Teslić in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[13]

Marko Snoj proposes the derivation from a Slavic form *Prišьčь, a possessive adjective from the personal name *Prišьkъ, (preserved in the Kajkavian surname Prišek, in the Old Polish personal name Parzyszek, and in the Polish surname Pryszczyk) and the derivational suffix -ina 'belonging to X and his kin'. The name is most likely a patronymic of the personal name *Prišь, preserved as a surname in Sorbian Priš, and Polish Przybysz, a hypocoristic of the Slavic personal name Pribyslavъ.[14] According to Aleksandar Loma, Snoj's etymology would presuppose a rare and relatively late word formation process.[13]

A false etymology connects the name Priština with the Serbian word prišt (пришт), meaning 'ulcer' or 'tumour', referring to its 'boiling'.[15] However, this explanation cannot be correct, as Slavic place names ending in -ina corresponding either or both to an adjective or the name of an inhabitant lacking this suffix are built from personal names or denote a person and never derive, in these conditions, from common nouns (SNOJ 2007: loc. cit.). The inhabitants of this city call themselves Prishtinali in local Gheg Albanian or Prištevci (Приштевци) in the local Serbian dialect.

Geography

Pristina covers an area of 572 square kilometres (221 sq mi). Strategically placed in the north-eastern part of Kosovo, the city is close to the Goljak mountains. Due to its status as the capital city of Kosovo, Pristina has grown over the past years, that it has connected with Kosovo Polje. By road it is 520 kilometres (320 mi) south of Belgrade, 90 kilometres (56 mi) north of Skopje, 250 kilometres (160 mi) north-east of Tirana, and 300 kilometres (190 mi) east of Podgorica.

Pristina is one of the urban areas with the most severe water shortages in the nation.[16] The population of the city have to cope with daily water curbs due to the lack of rainfall and snowfall which has left the city's water supplies in a dreadful condition.[16] The water resources do not fulfil the needs of the overgrowing population of Pristina. The water supply comes from the two main reservoirs of Batlava and Badovc.[16] However, there are many problems with the water supply that comes from these two reservoirs which supply 92% of the population in Pristina.[17] As such, the authorities have increased their efforts to remedy the situation and to make sure that such crises do not hit the city again.[18]

After the war of 1999, the city has changed dramatically. The City Park of Pristina has been fully changed with new stone pathways, tall trees, flowers have been planted and a public area has been built for children. Lately a new green place called Tauk Bashqe has been built halfway between the Gërmia and the City Park. After the reconstruction of the Mother Teresa Square, many trees and flowers have been planted. Many old buildings in front of the government building have been cleared to provide open space.

Climate

Pristina has either a humid continental climate under the Köppen climate classification (Dfb) or an oceanic climate (Cfb). The city enjoys warm summers and relatively cold, often snowy winters.

| Climate data for Pristina (1961–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.8 (60.4) |

20.2 (68.4) |

26.0 (78.8) |

29.0 (84.2) |

32.3 (90.1) |

36.3 (97.3) |

39.2 (102.6) |

36.8 (98.2) |

34.4 (93.9) |

29.3 (84.7) |

22.0 (71.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

39.2 (102.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.5 (50.9) |

15.7 (60.3) |

20.7 (69.3) |

23.9 (75.0) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.7 (80.1) |

23.1 (73.6) |

17.1 (62.8) |

10.1 (50.2) |

4.1 (39.4) |

15.5 (59.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.3 (29.7) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.9 (49.8) |

14.7 (58.5) |

17.8 (64.0) |

19.7 (67.5) |

19.5 (67.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

10.6 (51.1) |

5.1 (41.2) |

0.4 (32.7) |

9.8 (49.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4.9 (23.2) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

0.2 (32.4) |

4.2 (39.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

11.4 (52.5) |

12.5 (54.5) |

12.3 (54.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

5.0 (41.0) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

4.4 (39.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.2 (−17.0) |

−24.5 (−12.1) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

0.5 (32.9) |

3.9 (39.0) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−17.6 (0.3) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−27.2 (−17.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 38.9 (1.53) |

36.1 (1.42) |

38.8 (1.53) |

48.8 (1.92) |

68.2 (2.69) |

60.3 (2.37) |

51.6 (2.03) |

44.0 (1.73) |

42.1 (1.66) |

45.4 (1.79) |

68.2 (2.69) |

55.5 (2.19) |

597.9 (23.54) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 13.6 | 12.3 | 11.4 | 12.1 | 12.8 | 11.9 | 8.3 | 7.9 | 7.5 | 8.6 | 12.3 | 14.5 | 133.2 |

| Average snowy days | 10.2 | 8.3 | 6.2 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 3.4 | 8.1 | 38.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83 | 77 | 70 | 65 | 67 | 67 | 63 | 62 | 68 | 74 | 80 | 83 | 71 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 70.8 | 96.0 | 143.0 | 184.0 | 227.9 | 246.3 | 299.3 | 289.6 | 225.8 | 173.5 | 96.9 | 70.2 | 2,123.3 |

| Source: Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia[19] | |||||||||||||

History

![]() Roman Empire c. 28 BC– 330 AD

Roman Empire c. 28 BC– 330 AD

![]() Byzantine Empire c. 330–c. 850

Byzantine Empire c. 330–c. 850

![]() First Bulgarian Empire c. 850–c. 1018

First Bulgarian Empire c. 850–c. 1018

![]() Byzantine Empire c. 1018–1040

Byzantine Empire c. 1018–1040

![]() Peter Delyan's Bulgaria 1040–1041

Peter Delyan's Bulgaria 1040–1041

![]() Byzantine Empire 1041–1072

Byzantine Empire 1041–1072

![]() Constantine Bodin's Bulgaria 1072

Constantine Bodin's Bulgaria 1072

![]() Byzantine Empire 1072–1180

Byzantine Empire 1072–1180

![]() Serbian Grand Principality 1180–1217

Serbian Grand Principality 1180–1217

![]() Second Bulgarian Empire 1218–c. 1241

Second Bulgarian Empire 1218–c. 1241

![]() Kingdom of Serbia c. 1241–1346

Kingdom of Serbia c. 1241–1346

![]() Serbian Empire c. 1346–1389

Serbian Empire c. 1346–1389

![]() Ottoman Empire 1389–1689

Ottoman Empire 1389–1689

![]() Holy Roman Empire 1689–1690

Holy Roman Empire 1689–1690

![]() Ottoman Empire 1690–1912

Ottoman Empire 1690–1912

![]() Kingdom of Serbia 1912–1915

Kingdom of Serbia 1912–1915

![]() Bulgarian occupation of Serbia 1915–1918

Bulgarian occupation of Serbia 1915–1918

![]() Kingdom of Serbia 1918

Kingdom of Serbia 1918

![]() Kingdom of Yugoslavia 1918–1941

Kingdom of Yugoslavia 1918–1941

![]() Italian protectorate of Albania 1941–43

Italian protectorate of Albania 1941–43

![]() German occupation of Albania 1943–44

German occupation of Albania 1943–44

![]() NKOJ 1944–45

NKOJ 1944–45

![]() SFR Yugoslavia 1945–1992

SFR Yugoslavia 1945–1992

![]() FR Yugoslavia 1992–1999

FR Yugoslavia 1992–1999

![]() UNMIK 1999–2008

UNMIK 1999–2008

Early development

The earliest traces of human life in the area date from the Paleolithic period, with further traces in the Mesolithic and Neolithic. The succeeding Starcevo, Vinca, Bubanj-Hum and Baden cultures were active in the region.[20]

The area what is now Pristina has been inhabited for nearly 10,000 years.[21] Early Neolithic findings were discovered dating as far back as the 8th century BC, in the areas surrounding Pristina, which includes Matiçan, Gracanica and Ulpiana.[21][22] In the 4th century BC, King Bardyllis brought various Illyrian tribes together in the region, establishing the Dardanian Kingdom.[7][8][9]

After the Roman conquest of Illyria in 168 BC, Romans colonized and founded several cities in the region which they named Dardania.[23] Ulpiana was one of the most important Roman cities in the Balkans and in the 2nd century BC it became a municipium. The city suffered tremendous damage from an earthquake in 518 AD.[24] The Byzantine Emperor Justinian I rebuilt the city in great splendor and renamed it Justiniana Secunda, but with the arrival of Slav tribes in the 6th century the city again fell into disrepair.[24]

Middle Ages

_05.JPG.webp)

Between the 5th and the 9th century the area was part of the Byzantine Empire. In the middle of the 9th century the area of modern Pristina was ceded to the First Bulgarian Empire. In the early 11th century it fell under Byzantine rule and the area was included into a province called Bulgaria. Between the late 11th and middle of the 13th century it was ceded several times to the Second Bulgarian Empire.

Pristina was an important town in late Medieval Serbia. The župe (counties) of Sitnica and Lipljan, which had territory around present-day Pristina, are mentioned in Life of Saint Simeon, a text written by the Serbian historical figure Saint Sava between 1201 and 1208. The city was also a royal estate of Stefan Milutin, Stefan Uroš III, Stefan Dušan, Stefan Uroš V and Vuk Branković.[10][25] The medieval fort of Višegrad, whose ruins lie three kilometres east of the city centre, was mentioned in Milutin's time,[26] and served as his capital,[27] and the nearby Gračanica monastery was founded by him in ca. 1315.

The first historical record mentioning Pristina by its name dates back to 1342 when the Byzantine Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos described Pristina as a 'village'.[21]

Between the end of the 14th and the middle of the 15th century, Ottoman rule was gradually imposed in the town.

Ottoman Empire

In the course of the 14th and 15th centuries, Pristina developed as an important mining and trading center thanks to its proximity to the rich mining town of Novo Brdo, and due to its position of the Balkan trade routes. The old town stretching out between the Vellusha and Prishtevka rivers which are both covered over today, became an important crafts and trade center. Pristina was famous for its annual trade fairs (Panair)[21] and its goat hide and goat hair articles. Around 50 different crafts were practiced from tanning to leather dying, belt making and silk weaving, as well as crafts related to the military – armorers, smiths, and saddle makers. As early as 1485, Pristina artisans also started producing gunpowder. Trade was thriving and there was a growing colony of Ragusan traders (from modern day Dubrovnik) providing the link between Pristina's craftsmen and the outside world.[21] The first mosque was constructed in the late 14th century while still under Serbian rule.[21] The 1487 defter recorded 412 Christian and 94 Muslim households in Pristina, which at the time was administratively part of the Sanjak of Vučitrn. In the early Ottoman era, Islam was an urban phenomenon and only spread slowly with increasing urbanization. The travel writer Evliya Celebi, visiting Pristina in the 1660s was impressed with its fine gardens and vineyards.[21] In those years, Pristina was part of the Vıçıtırın Sanjak and its 2,000 families enjoyed the peace and stability of the Ottoman era. Economic life was controlled by the guild system (esnafs) with the tanners' and bakers' guild controlling prices, limiting unfair competition and acting as banks for their members. Religious life was dominated by religious charitable organizations often building mosques or fountains and providing charity to the poor. During the Austro-Turkish War in the late 17th century, Pristina citizens under the leadership of the Catholic Albanian priest Pjetër Bogdani pledged loyalty to the Austrian army and supplied troops. He contributed a force of 6,000 Albanian soldiers to the Austrian army which had arrived in Pristina. Under Austrian occupation, The Fatih Mosque (Mbretit Mosque) was briefly converted to a Jesuit church.[21] Following the Austrian defeat in January 1690, Pristina's inhabitants were left at the mercy of Ottoman and Tatar troops who took revenge against the local population as punishment for their co-operation with the Austrians. A French officer traveling to Pristina noted soon afterwards that "Pristina looked impressive from a distance but close up it is a mass of muddy streets and houses made of earth".[21]

Modern period

The year 1874 marked a turning point. That year the railway between Salonika and Mitrovica started operations and the seat of the vilayet of Prizren was relocated to Pristina. This privileged position as capital of the Ottoman vilayet lasted only for a short while. from January until August 1912, Pristina was liberated from Ottoman rule by Albanian rebel forces led by Hasan Prishtina.[28] However, The Kingdom of Serbia opposed the plan for a Greater Albania, preferring a partition of the European territory of the Ottoman Empire among the four Balkan allies.[29] On October 22, 1912, Serb forces took Pristina. However, Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the first Balkan War, occupied Kosovo in 1915 and took Pristina under Bulgarian occupation.[30] In late October 1918, the 11th French colonial division took over Pristina and returned Pristina back to what then became the 'First Yugoslavia' on the 1st of December 1918.[30] In September 1920, the decree of the colonization of the new southern lands' facilitated the takeover by Serb colonists of large Ottoman estates in Pristina and land seized from Albanians.[30] The interwar period saw the first exodus of Albanian and Turkish speaking population.[21][30] From 1929 to 1941, Priština was part of the Vardar Banovina of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

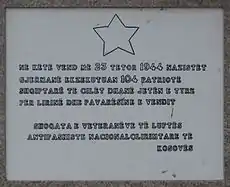

On 17 April 1941, Yugoslavia surrendered unconditionally to axis forces. On 29 June, Benito Mussolini proclaimed a greater Albania, with most of Kosovo under Italian occupation united with Albania. There ensued mass killings of Serbs, in particular colonists, and an exodus of tens of thousands of Serbs.[31][32] After the capitulation of Italy, Nazi Germany took control of the city. In May 1944, 281 local Jews were arrested by units of the 21st Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Skanderbeg (1st Albanian), which was made up mostly of Muslim Albanians. The Jews were later deported to Germany, where many were killed.[33][34] The few surviving Jewish families in Pristina eventually left for Israel in 1949.[21] As a result of World War II and forced migration, Pristina's population dropped to 9,631 inhabitants.[21]

The communist decision to make Pristina the capital of Kosovo in 1947 ushered a period of rapid development and outright destruction. The Yugoslav communist slogan at the time was uništi stari graditi novi (destroy the old, build the new). In a misguided effort to modernize the town, communists set out to destroy the Ottoman bazaar and large parts of the historic center, including mosques, catholic churches and Ottoman houses.[21] A second agreement signed between Yugoslavia and Turkey in 1953 led to the exodus of several hundreds more Albanian families from Pristina. They left behind their homes, properties and businesses.[21] However, this policy changed under the new constitution ratified in 1974. Few of the Ottoman town houses survived the communists' modernization drive, with the exception of those that were nationalized like today's Emin Gjiku Museum or the building of the Institute for the Protection of Monuments.

As capital city and seat of the government, Pristina creamed off a large share of Yugoslav development funds channeled into Kosovo. As a result, the city's population and its economy changed rapidly. In 1966, Pristina had few paved roads, the old town houses had running water and cholera was still a problem. Prizren continued to be the largest town in Kosovo. Massive investments in state institutions like the newly founded University of Pristina, the construction of new high-rise socialist apartment blocks and a new industrial zone on the outskirts of Pristina attracted large number of internal migrants. This ended a long period when the institution had been run as an outpost of Belgrade University and gave a major boost to Albanian-language education and culture in Kosovo. The Albanians were also allowed to use the Albanian flag.

Within a decade, Pristina nearly doubled its population from about 69,514 in 1971 to 109,208 in 1981.[21] This golden age of externally financed rapid growth was cut short by Yugoslavia's economic collapse and the 1981 student revolts. Pristina, like the rest of Kosovo slid into a deepening economic and social crisis. The year 1989 saw the revocation of Kosovo's autonomy under Milošević, the rise of Serb nationalism and mass dismissal of ethnic Albanians.[21]

Kosovo War

Following the reduction of Kosovo's autonomy by Serbian President Slobodan Milošević in 1989, a harshly repressive regime was imposed throughout Kosovo by the Yugoslav government with Albanians largely being purged from state industries and institutions.[21] The LDK's role meant, that when the Kosovo Liberation Army began to attack Serbian and Yugoslav forces from 1996 onwards, Pristina remained largely calm until the outbreak of the Kosovo War in March 1999. Pristina was spared large scale destruction compared to towns like Gjakova or Peć that suffered heavily at the hands of Serbian forces. For their strategic importance, however, a number of military targets were hit in Pristina during NATO's aerial campaign, including the post office, police headquarters and army barracks (today's Adem Jashari garrison on the road to Kosovo Polje).

Widespread violence broke out in Pristina. Serbian and Yugoslav forces shelled several districts and, in conjunction with paramilitaries, conducted large-scale expulsions of ethnic Albanians accompanied by widespread looting and destruction of Albanian properties. Many of those expelled were directed onto trains apparently brought to Pristina's main station for the express purpose of deporting them to the border of North Macedonia, where they were forced into exile.[35]

On, or about, 1 April 1999, Serbian police went to the homes of Kosovo Albanians in the city of Pristina/Prishtinë and forced the residents to leave in a matter of minutes. During the course of Operation Horseshoe, a number of people were killed. Many of those forced from their homes went directly to the train station, while others sought shelter in nearby neighbourhoods. Hundreds of ethnic Albanians, guided by Serb police at all the intersections, gathered at the train station and then were loaded onto overcrowded trains or buses after a long wait where no food or water was provided. Those on the trains went as far as Elez Han, a village near the Macedonian border. During the train ride many people had their identification papers taken from them.[36]

— War Crimes Indictment against Milošević and others

The majority Albanian population fled the town in large numbers to escape Serb policy and paramilitary units. The first NATO troops to enter Pristina in early June 1999 were Norwegian special forces from FSK Forsvarets Spesialkommando and soldiers from the British Special Air Service 22 S.A.S,[37][38] although to NATO's diplomatic embarrassment Russian troops arrived first at the airport. Apartments were occupied illegally and the Roma quarters behind the city park was torched. Several strategic targets in Pristina were attacked by NATO during the war, but serious physical damage appears to have largely been restricted to a few specific neighbourhoods shelled by Yugoslav security forces. At the end of the war the Serbs became victims of violence committed by Kosovo Albanian extremists. On numerous occasions Serbs were killed by mobs of Kosovo Albanian extremists for merely speaking Serbian in public or being identified as a Serb.[39] Violence reached its pinnacle in 2004 when mobs of Kosovo Albanian extremists were moving from apartment block to apartment block attacking and ransacking the residences of remaining Serbs.[40] Due to the continued violence almost all of the city's 45,000 Serb inhabitants fled from Kosovo and today only several dozen remain within the city.[41]

Contemporary

As a capital city and seat of the UN administration (UNMIK), Pristina has benefited greatly from a high concentration of international staff with disposable income and international organizations with sizable budgets. The injection of reconstruction funds from donors, international organizations and the Albanian diaspora has fueled an unrivaled, yet short-lived, economic boom. A plethora of new cafes, restaurants and private businesses opened to cater for new (and international) demand with the beginning of a new era for Pristina.

Politics

.jpg.webp)

Being the capital city of Kosovo, it influences the politic, culture and economic aspects of the country. Pristina is the seat of the Government of Kosovo. The Mayor of Pristina is one of the most influential political figures in the nation as well as serving as an urban figure through the youth of the city. Kosovo is known for having the youngest population in Europe, with an average of 25 years old.[42] During the 2013 elections, Shpend Ahmeti, a professor of economics, gathered most of the youth of Pristina around his campaign also due to the fact that he was nearly 30 years younger than the former Mayor Isa Mustafa. His team and staff consisted of young people and Ahmeti delivered a more modern public image, presenting himself closer to the voters. A lot of young people chose to volunteer in his meetings, therefore his campaign in general represented a novelty in Kosovan politics.[43] Ahmeti promised to go to work by public transport in order to save money from the use of expensive official cars and has been doing so until now.[44]

The city council consists of 51 members. One out of three of the members have to be women according to the Statute of the Municipality approved in 2010. The city council has seen the LDK having the most members in all elections held until now. In the 2013 elections, although LDK candidate Isa Mustafa lost to Shpend Ahmeti, the LDK won 18 seats in Assembly with Vetëvendosje with 10. The PDK followed with 8 seats and the AKR with 4.[45] The head of the City Council is Halim Halimi from the LDK.[46] In February 2014 a majority of the City Council after a heated debate, voted to sell the official car of the municipality in order to decrease the distance between the politicians and the population.[47]

Demography

| Demographic evolution of Pristina | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1948 | 1953 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2011 | 2016 |

| Pop. | 44,089 | 51,457 | 69,810 | 105,273 | 148,656 | 199,654 | 198,897 | 204,721 |

| ±% p.a. | — | +3.14% | +3.89% | +4.19% | +3.51% | +2.99% | −0.02% | +0.58% |

| Source: [48] | ||||||||

In the 2011 census, the total population of the municipality of Pristina was estimated at 198,897, with 145,149 in the city proper, constituting the largest city of Kosovo by population.[49] The most commonly nominated ethnic groups were Albanian (97.8%), Turkish (1%), Ashkali (0.28%), Serbian (0.22%), Bosnian (0.20%), Gorani (0.10%), Romani (0.03%) and Egyptian (0.001%).[50]

The rural area as well as the area near the center of Pristina, in terms of socio-economic processes, is under the influence of population dynamics, both in terms of demographic regime, which is more expansive, and in addition mechanical population. This part of the municipality has a high density of population. The density of population is 247 inhabitants per square kilometres.[51] While the population density of suburban area of the municipality without Pristina, as an urban center, is 123 inhabitants per km²[52]

As an urban center with representative functions and its economic strength, has changed the population structure. With the surrounding space has become increasingly a concentration to a large population. While the mountain area, especially more distant areas have a displacement due to depopulation, especially after the Kosovo War. The network of settlements in the territory of the Municipality of Pristina has some specifics. Such as distribution of settlements depends on the degree of economic development, natural conditions, socio-political circumstances, position. One of the features is also uneven distribution of the settlements.

According to the census done in 1991 (boycotted by the Albanian majority), the population of the Pristina municipality was 199,654, including 77.63% Kosovo Albanians, 15.43% Kosovo Serbs and Montenegrins, 1.72% of ethnic Muslims and others.[53] This census cannot be considered accurate as it is based on previous records and estimates. In early 1999, Pristina had around 230,000 inhabitants. There were more than 40,000 Serbs and about 6,500 Roma with the remainder being Kosovo Albanians.

Today, after new administrative division was established in the 2000s, the city of Pristina has Kosovo Albanians ethnic majority amounting to 98% of total population with small number of minorities. The Serbian population in the city has fallen significantly since 1999, as many of the Serbs who lived in the city have fled or been expelled following the end of the war. Also, many of them moved to the municipality of Gračanica, expanded municipality located southern of Pristina.

Religion

Kosovo is a secular state with no state religion. The freedom of belief, conscience and religion is explicitly guaranteed in the Constitution of Kosovo.[54][55]

Islam and Christianity are the most widely practiced religions among the people of Pristina. In the 2011 census, 97.3% of the population of the city was counted as Muslim and 0.8% as Christian including 0.59% as Roman Catholic and 0.24% as Eastern Orthodox.[56] The remaining 1.9% of the population reported having no religion, or another religion, or did not provide an adequate answer.[56]

Pristina has centres of worship for a multitude of faiths for its population. The Cathedral of Pristina is perhaps the largest cathedral in Kosovo and is named in honour of the Albanian Roman Catholic nun and missionary, Mother Teresa. Some of the mosques of Pristina, among others the Imperial Mosque and Çarshi Mosque, are centuries old and were built during the Middle Ages by the Ottomans.

Economy

Pristina constitutes the heart of the economy of Kosovo and of vital importance to the country's stability. The tertiary sector is the most important for the economy of the city and employs more than 75% of work force of Pristina.[57] 20% of the working population makes up the secondary sector followed by the primary sector with only 5%.[57]

Pristina is the primary tourist destination in Kosovo as well as the main air gateway to the country.[58] It is known as a university center of students from neighbouring countries as Albania, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia. In 2012, Tourism in Pristina attracted around 100,000 foreign visitors.[59] which represents 74.2%[60] Most foreign tourists come from Albania, Turkey, Germany, United States, Slovenia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, with the number of visitors from elsewhere growing every year.[61]

The city has a large number of luxury hotels, modern restaurants, bars, pubs and very large nightclubs. Coffee bars are a representative icon of Pristina and they can be found almost everywhere. The largest hotels of the city are the Swiss Diamond and the Grand Hotel Prishtina situated in the heart of the city. Other major hotels present in Pristina include the Emerald Hotel, Sirius Hotel and Hotel Garden.

Some of the most visited sights near the city include the Batlava Lake and Marble Cave, which are also among the most visited places in country.[62] Pristina has played a very important role during the World War II, being a shelter for Jews, whose cemeteries now can be visited.[63][64][65]

Infrastructure

Transport

Pristina constitutes the economic and financial heart of Kosovo, in part due to its high population, modern infrastructure and geographical location in the center of the country. Following the independence of Kosovo, the city has undergone significant improvements and developments vastly modernising and expanding the economy, infrastructure and most notably transportation by air, rail and road.[66]

Pristina is the most important and frequent road junction of Kosovo as all of the major expressways and motorways passes through the city limits. Most of the motorways of Kosovo are largely completed and partially under construction or under planning process. Immediately after completion, Pristina will provide direct access to Skopje through the R6 motorway.[67] The R7 motorway significantly connects Durrës with Prishtina and will have near future a direct connection to the Pan-European corridor X.[68]

The international airport of Pristina serves as the premier gateway to the country and carries almost 2 million passengers per year with connections to many destinations around different countries and cities of Europe with the most frequent routes to Austria, Germany, Switzerland as well as to Slovenia, Turkey and the United Kingdom.[69]

Pristina is the transport hub of road, rail and air in Kosovo. The city's buses, trains and planes together all serve to maintain a high level of connectivity between Pristina many different districts and beyond. Analysis from the Traffic Police have shown that, of 240,000 cars registered in Kosovo, around 100,000 (41%) are from the region of Pristina. The Pristina railway station is located near the city centre.

Pristina effectively has two train stations. Pristina railway station lies west of the center, while Fushë Kosovë railway station is Kosovo's railway hub.[70] Pristina is serviced by a train that travels through Pristina to Skopje daily. The station is located in the industrial section of Pristina.

Education

Pristina is the center of education in the country and home to many public and private primary and secondary schools, colleges, academies and universities, located in different areas across the city. The University of Pristina is the largest and oldest university of the city and was established in the 20th century.

Finance, arts, journalism, medicine, dentistry, pharmaceuticals, veterinary programs, and engineering are among the most popular fields for foreigners to undertake in the city. This brings a many of young students from other cities and countries to Pristina. It is known for its many educational institutions such as University of Pristina, University of Pristina Faculty of Arts and the Academy of Sciences and Arts of Kosovo.

Among the first schools known in the city were those opened during the Ottoman period.[71] Albanians were allowed to attend these schools, most of which were religious, with only few of them being secular.[71]

The city has numerous libraries, many of which contain vast collections of historic and cultural documents. The most important library in terms of historic document collections is the National Library of Kosovo.

Media

Media in Pristina include some of the most important newspapers, largest publishing houses and most prolific television studios of Kosovo. Pristina is the largest communications center of media in Kosovo. Almost all of the major media organizations in Kosovo are based in Pristina.[72] The television industry developed in Pristina and is a significant employer in the city's economy. The four major broadcast networks, RTK, RTV21, KTV and KLAN KOSOVA are all headquartered in Pristina. Radio Television of Kosovo (RTK) is the only public broadcaster both in Pristina and in all of Kosovo as well, who continues to be financed directly by the state. All of the daily newspapers in Pristina have a readership throughout Kosovo. [73] An important event which affected the development of the media, is that in University of Pristina since 2005 is established the Journalism Faculty within the Faculty of Philology in which are registered a large number of youth people.[74]

Culture

As the capital city of the Republic of Kosovo, it is the center of cultural and artistic development of all Albanians that live in Kosovo. Pristina is home to the largest cultural institutions of the country, such as the National Theatre of Kosovo, National Archaeology, Ethnography and Natural science Museum, National Art Gallery and the Ethnological Museum. The National Library of Kosovo has than 1.8 million books, periodicals, maps, atlases, microfilms and other library materials.

There are many foreign cultural institutions in Pristina, including the Albanian Albanological Institute, the French Alliance Française,[75] the British Council,[76] and the German Goethe-Institut[77] and Friedrich Ebert Foundation.[78] The Information Office of the Council of Europe was also established in Pristina.[79]

Of 426 protected historical monuments in Kosovo, 21 are in Pristina.[80] A large number of these monuments date back to the Byzantine and Ottoman periods.[81]

Starting in 1945, the Yugoslav authorities began constructing a modern Pristina with the idea of "destroy the old, build the new".[82] This modernization led to major changes in the structure of the buildings, their function and their surrounding environment.[83]

However, numerous types of monuments have been preserved, including four mosques, a restored orthodox church, an Ottoman bath, a public fountain, a clock tower, several traditional houses as well as European-influenced architecture buildings such as Kosovo Museum.[84] These symbolize the historical and cultural character of Pristina as it was developed throughout centuries in the spirit of conquering empires (Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian).[81]

The Hivzi Sylejmani library was founded 70 years ago and it is one of the largest libraries regarding the number of books in its inventory which is nearly 100.000. All of those books are in service for the library's registered readers.[85]

The Mbretëresha e Dardanisë (Queen of Dardania) or Hyjnesha ne Fron (The Goddess on the Throne) is an artifact that was found during some excavations in 1955[86] in the area of Ulpiana,[87] a suburb of Pristina. It dates back to 3500 BC in the Neolithic Era and it is made of clay.[88] In Pristina there is also "Hamami i Qytetit"(The City Bath) and the house of Emin Gjika which has been transformed to the Ethnographic Museum. Pristina also has its municipal archive which was established in the 1950s and holds all the records of the city, municipality and the region.[85]

Music

Albanian music is considered to be very rich in genres and their development. But before talking about genre development, a key point that has to be mentioned is without doubt the rich folklore of Kosovo most of which unfortunately has not been digitalized and saved in archives. The importance of folklore is reflected in two main keys, it is considered a treasure" of cultural heritage of our country and it helps to enlighten the Albanian history of that time, and the importance of that is of a high level especially when mentioning the circumstances of our territory in that time.[89][90] Folklore has also served as inspiration and influence in many fields including music composition in the next generations[91] One of the most notable and very first composers, Rexho Mulliqi in whose work, folklore inspiration and influence is very present.[92]

When highlighting the music creativity and its starts in Kosovo and the relation between it and the music creativity in Albania even though they have had their development in different circumstances, it is proved that they share some characteristics in a very natural way. This fact shows that they belong to one "Cultural Tree".

Some of few international music artists of Albanian heritage are born and raised in the city including Rita Ora, Dua Lipa and Era Istrefi.

Theater

The city of Pristina hosts only three active theatres such as the National Theater, Oda and Dodona Theatre placed in center of Pristina. They offers live performances every week. The National Theatre is placed in the middle downtown of the city, near the main government building and was founded in 1946.[93] ODA Theatre is situated in the Youth Centre Building and Dodona Theatre is placed in Vellusha district, which is near Ibrahim Rugova Square.

The National Theater of Kosovo is the highest ranked theater institution in the country which has the largest number of productions. The theater is the only public theater in Kosovo and therefore it is financed by Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sport. This theater has produced more than 400 premieres which have been watched by more than 3 million spectators.[94]

Festivals

Festivals and events are one of some things that people in Pristina enjoy properly, without rushing to get it over with. Despite having quite a small territorial space, Pristina has a pleasant number of festivals and events. The diversity of festivals makes it possible for people of different tastes to find themselves in a city this small.

The Prishtina International Film Festival screens prominent international cinema productions in the Balkan region and beyond, and draws attention to the Kosovar film industry. It was created after the 2008 Kosovo declaration of independence. After its independence in 2008, Kosovo looked for ways to promote its cultural and artistic image.

One of major festivals include the Chopin Piano Fest Pristina that was established for the first time on the occasion of the 200th birth anniversary of Frédéric Chopin in 2010 by the Kosovo Chopin Association.[95] The festival is becoming a traditional piano festival held in spring every year. It is considered to be a national treasure.[96] In its 5 years of formation it has offered interpretations by both world-famous pianists such as Peter Donohoe, Janina Fialkowska, Kosovo-Albanian musicians of international renown like Ardita Statovci, Alberta Troni and local talents.[97][96] The Festival strives to promote the art of interpretation, the proper value of music and the technicalities that accompany it.[96] The Festival has served as inspiration for the formation of other music festivals like Remusica and Kamerfest.[97]

The DAM Festival Pristina is one of the most prominent cultural events taking place in the capital. It is an annual music festival which gathers young and talented national and international musicians from all over the world. This festival works on enriching the Kosovar cultural scene with the collision of the traditional and the contemporary. The festival was founded by back then art student, now well known TV producer, musician, journalist and manager of the Kosovo's Philharmonic Orchestra, Dardan Selimaj.[98]

Pristina had always a development in trading due to its position of the Balkan trade routes. Fairs started since the medieval period, at the time when it was famous for its annual trade fairs and its goat hide and goat hair articles. Despite that fact Pristina, or Kosovo in general is not known for occurrence of fairs. With the development of culture and especially after the last war in 1999, Pristina had a progress on holding these kinds of events. Every year various types of trade fairs take place in the capital city. The essence of these fairs is usually temporary; some last only an afternoon while others may last around 3 days, a week or even longer. They have grown in size and importance over the years. These fairs are organized annually and are open to trade visitors and public. The number of exhibitors and visitors is usually very high.

Sports

Pristina is the center of sport in Kosovo, where activity is organized across amateur and professional levels, sport organizations and clubs, regulated by the Kosovo Olympic Committee and the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sport.[99] Sport is organized in units called Municipal Leagues. There are seven Municipal Leagues in Pristina. The Football Municipal consists of 18 clubs, the Basketball Municipal 5 clubs, the Handball Municipal 2 clubs, Table Tennis and Chess 6 clubs each, the Karate Municipal 15 and the Tennis Municipal 2 clubs.[100]

Football is the most popular sport in the city. It is represented by FC Prishtina, which plays their home games in the Fadil Vokrri Stadium. Basketball has been also one of the most popular sports in Pristina and is represented by KB Prishtina. It is the most successful basketball club in Kosovo and is part of the Balkan League.[101] Joining it in the Superleague is another team from Pristina, RTV 21.[102]

Streetball is a traditionally organised sport and cultural event at the Germia Park since 2000. Apart from indoor basketball success, Che Bar team has been crowned the champion of the national championship in 2013. This victory coincided with Streetball Kosovo's acceptance in FIBA.[103] Handball is also very popular. Pristina's representatives are recognised internationally and play international matches.

See also

Notes

- Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008. Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the 2013 Brussels Agreement. Kosovo is currently recognized as an independent state by 98 out of the 193 United Nations member states. In total, 113 UN member states recognized Kosovo at some point, of which 15 later withdrew their recognition.

References

- "Define – Pristina". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- "Pristina". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- "Pristina". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- "Pristina". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- Prishtina Development Plan Document: http://prishtinaonline.com/uploads/prishtina_pzhk_2012-2022_shqip%20(1).pdf

- Official gov't census: http://esk.rks-gov.net/rekos2011/repository/docs/REKOS%20LEAFLET%20ALB%20FINAL.pdf Archived 2011-11-12 at the Wayback Machine

- , The Cambridge ancient history: The fourth century B.C. Volume 6 of The Cambridge ancient history, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards, ISBN 0-521-85073-8, ISBN 978-0-521-85073-5, Authors: D. M. Lewis, John Boardman, Editors: D. M. Lewis, John Boardman, Edition 2, Publisher: Cambridge University Press, 1994 ISBN 0-521-23348-8, ISBN 978-0-521-23348-4.

- Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). James P. Mallory (ed.). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- Wilson, Nigel Guy (2006). Encyclopedia Of Ancient Greece. Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-0-415-97334-2.

- Zadruga, Srpska Književna (1913). Izdanja. p. 265.

- Warrander, Gail; Verena Knaus (2010). Kosovo. Bradt Travel Guides Ltd, UK. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-84162-331-3.

- Warrander, Gail; Verena Knaus (2010). Kosovo. Bradt Travel Guides Ltd, UK. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-84162-331-3.

- Loma, Aleksandar (2013), "Топонимија Бањске хрисовуље" [Toponymy of the Banjska Chrysobull], Onomatološki Prilozi (in Serbian), Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts: 181, ISSN 0351-9171

- SNOJ, Marko. 2007. Origjina e emrit të vendit Prishtinë. In: BOKSHI, Besim (ed.). Studime filologjike shqiptare: konferencë shkencore, 21–22 nëntor 2007. Prishtinë: Akademia e Shkencave dhe e Arteve e Kosovës, 2008, pp. 277–281.

- This etymology is mentioned in ROOM, Adrian: Placenames of the World, Second Edition, McFarland, 2006, page 304. ISBN 0-7864-2248-3

- "Winter Drought Threatens Kosovo Capital's Water". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT OF WATER SERVICE PROVIDERS IN KOSOVO,IN 2012" (PDF). Water and Waste Regulatory Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Zogjani, Nektar (2014-01-08). "Uji Për Prishtinën Në Dorë Të Zotit". Gazeta Jeta në Kosovë. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "Pristina: Monthly and annual means, maximum and minimum values of meteorological elements for the period 1961–1990". Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Ajdini, Sh.; Bytyqi, Q.; Bycinca, H.; Dema, I.; et al. (1975), Ferizaj dhe rrethina, Beograd, pp. 43–45

- Warrander, Gail (2007). Kosovo: The Bradt Travel Guide. Bradt Travel Guides Ltd., 23 high street, chalfont st peter, bucks SL9 9QE, England: The Globe Pequot Press Inc. pp. 85–88. ISBN 978-1-84162-199-9. Retrieved 2013-05-18.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Chapman 2000, p. 239

- Hauptstädte in Südosteuropa: Geschichte, Funktion, nationale Symbolkraft by Harald Heppner, p. 134

- Archaeological Guide of Kosovo Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sport, Archaeological Institute of Kosovo, Pristina 2012

- Lekić, Đorđe (1995). Kosovo i metohija tokom vekova: Zublja. p. 22.

- Panić-Surep, Milorad (1965). Yugoslavia: Cultural Monuments of Serbia. p. 167.

- Vlahović, Petar (2004). Serbia: The country, people, life, customs. p. 392. ISBN 9788678910319.

- Bogdanović, Dimitrije (November 2000) [1984]. "Albanski pokreti 1908–1912.". In Antonije Isaković (ed.). Knjiga o Kosovu (in Serbian). 2. Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

... ustanici su uspeli da ... ovladaju celim kosovskim vilajetom do polovine avgusta 1912, što znači da su tada imali u svojim rukama Prištinu, Novi Pazar, Sjenicu pa čak i Skoplje ... U srednjoj i južnoj Albaniji ustanici su držali Permet, Leskoviku, Konicu, Elbasan, a u Makedoniji Debar ...

- Josef Redlich, Baron d'Estournelles, M. Justin Godart, Walter Shucking, Francis W. Hirst, H. N. Brailsford, Paul Milioukov, Samuel T. Dutton (1914). "Report of the International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and the Conduct of the Balkan Wars". Washington D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Piece. p. 47. Retrieved January 10, 2011.

This demonstration of Turkish weakness encouraged new allies, the more so that the promises of Albanian autonomy, covering the four vilayets of Macedonia and Old Servia, directly threatened the Christian nationalities with extermination.

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Kosovo. estover road plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom: Scarecrow Press, Inc. pp. xxxiv. ISBN 978-0-8108-7231-8. Retrieved 2013-05-18.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Murray 1999, p. 15.

- Sabrina P. Ramet The three Yugoslavias: state-building and legitimation, 1918–2005

- Fischer, Bernd Jürgen (1999). Albania at War, 1939–1945. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue Research Foundation. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-55753-141-4.

- Mojzes, Paul (2011). Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the 20th Century. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-1-4422-0665-6.

- "Kosovo Albanians 'driven into history'". BBC. April 1, 1999. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- "Indictment against Milosevic and others". Americanradioworks.publicradio.org. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- "Krigere og diplomater". norli.no. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- "Tittel". norli.no. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- "Serbs shot in mob attack". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "The Violence: Ethnic Albanian Attacks on Serbs and Roma". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "EuroNews Serbs in Kosovo vote in Gracanica and Mitrovica published February 3, 2008 accessed February 3, 2008". Euronews.net. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-05. Retrieved 2014-03-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Front Page - Gazeta Tribuna". Gazeta Tribuna. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "Gazeta Tema - Gazeta më e lexuar Shqiptare". www.gazetatema.net. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-01-09. Retrieved 2015-01-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.zeri.info/artikulli/25226/halimi-kryesues-i-asamblese-komunale-te-Prishtinës%5B%5D

- "Miratohet shitja e makinës Audi Q7". Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "Division of Kosovo". pop-stat.mashke.org.

- "Estimation of Kosovo population 2011" (PDF). Pristina: Agjencia e Statistikave të Kosovës (ASK). February 2013. p. 30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- "Ethnic composition of Kosovo 2011". pop-stat.mashke.org.

- "Density of Population". Agency of State Archives of Kosovo (in Albanian). 3 August 2012. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- Riza Qavolli ,"Gjeografia Regjionale e Kosoves page.157"

- Statistic data for the municipality of Priština – grad

- "Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo" (PDF). kryeministri-ks.net. p. 17.

- "KOSOVO 2017 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT" (PDF). state.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-05-29.

- "Religious composition of Kosovo 2011". pop-stat.mashke.org (in Albanian).

- "Bizneset dhe rrethina e biznesit". kk-arkiva.rks-gov.net (in Albanian).

- +Jugoslav Spasevski. "Kosovo". Tourist Destinations. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- "Hotel Statistics in Q3 2013 (Alb. Statistikat e hotelierisë TM3 2013)" (PDF). Kosovo Agency of Statistics. 2013. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-02. Retrieved 2014-03-06.

- "Kosovo Agency of Statistics, 'Hotel Statistics in Q3 2013'" (PDF). Kosovo Agency of Statistics. 2013. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-02. Retrieved 2014-03-06.

- "Kosovo Agency of Statistics, 'Statistikat e hotelierisë TM3 2013'" (PDF). Kosovo Agency of Statistics. 2013. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-02. Retrieved 2014-03-06.

- "12 thousand foreign tourists visited Kosovo (alb. 12 mijë turistë të huaj e vizituan Kosovën)". 2013. Archived from the original on 2018-12-03. Retrieved 2014-03-06.

- "Kosovo Virtual Jewish History Tour". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "Kosovo's Jewish Cemetery Restored By University Students (PHOTOS)". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- Material Culture and the history of the city of Prishtina (Alb. Kultura materiale dhe historia e qytetit të Prishtinës),

- Komuna e Prishtinës: Investime të mëdha në infrastrukturë Archived 2010-07-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- "ROUTE 6: HIGHWAY PRISHTINA - SKOPJE" (PDF). kfos.org. 2015. pp. 29–35.

- "ROUTE 6: HIGHWAY PRISHTINA - SKOPJE" (PDF). kfos.org. 2015. pp. 13–28.

- "Statistics on passengers and flights at PIA Adem Jashari 2016" (PDF). caa-ks.org. Civil Aviation Authority of Kosovo. 2 January 2019. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2017.

- "Trains - Arrival & Transport in Pristina - In Your Pocket city guide - essential travel guides to cities in Kosovo". inyourpocket.com. Archived from the original on 2014-03-02. Retrieved 2014-03-02.

- "The History, Culture and Identity of Albanians in Kosovo", Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, The History, Culture and Identity of Albanians in Kosovo, 1 May 1997,accessed 23 February 2014.

- Kosovo Media Institute Major media organizations in Kosovo and their addresses.

- "OSCE". Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- "Fakulteti i Filologjisë - Ballina". Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- "Alliance Française de Prishtina". Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "British Council - Kosovo". kosovo.britishcouncil.org. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "Sprachlernzentrum in Prishtina". www.slzprishtina.org. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "Welcome, Office Prishtina, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung e.V. - Home". www.fes-prishtina.org. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "Home". Council of Europe Office in Pristina. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "Një e ardhme për të kaluarën e Pishtinës" (PDF) (in Albanian). Kosova Stability Initiative, European Stability Initiative. p. 9. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- Limani, Jeta. "Kulla of Mazrekaj family in Dranoc" (PDF). p. 2.

- Warrander, Gail; Verena Knaus (2010). Kosovo. Bradt Travel Guides Ltd., UK. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-84162-331-3.

- "CONSERVATION BASIS FOR THE "HISTORIC CENTRE" OF PRISHTINË" (PDF) (in English, Albanian, and Serbian). December 2012. p. 3.

- "Conservation Basis for the "historic Centre" of Prishtinë" (PDF) (in English, Albanian, and Serbian). December 2012. p. 16.

- Letërnjoftim i shkurtër për kulturën e kryeqytetit Archived 2015-04-05 at the Wayback Machine Short notice of capital culture. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- 'Tjerrtorja' Archaeological Site (listed since 1955). Retrieved 1 March 2014

- Goldsworthy, Adrian Keith; Haynes, Ian; Adams, Colin E. P. (1997). The Roman army as a community. Journal of Roman Archaeology. p. 100. ISBN 1887829342. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Idhulli i Dardanisë apo Hyjnesha në fron Dardanian idol or Goddess on the Throne. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- Rudi, Rafet (2002). Sprova Estetike - Muzika e shekullit XX (Esthetical Challenges" - Music of the 20th Century). Dukagjini. p. 135.

- "Portali Shqiperia".

- "Gazeta Jeta në Kosovë - Kosovë - Gazeta Jeta në Kosovë". Gazeta Jeta në Kosovë.

- "Zeri.info - Rexho Mulliqi- Nismëtar i muzikës artistike në Kosovë". zeri.info. Archived from the original on 2014-03-02.

- "The National theatre of Kosovo".

- "Profili". Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- Luzha, Besa. "Chopin Piano Fest Prishtina". WordPress. Archived from the original on 2014-01-10. Retrieved 2014-02-23.

- Selmani, Arber. "'Chopin Fest' eshte pasuri shteterore". Archived from the original on 2014-03-02. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- ""Chopin Piano Fest", në kujtim të Verdit". Koha Net. Archived from the original on 2014-03-02. Retrieved 2014-02-23.

- "DAM Festival-KadMusArts". Archived from the original on 2014-03-02. Retrieved 2014-03-06.

- "Departamenti i Sportit:Profili". Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- "Sport". Archived from the original on 28 November 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "Sigal Prishtina hap etapën e re në basketboll". Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- "ETC SUPERLIGA". Archived from the original on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- "Che Bar kampione e Kosovës në Streetball". Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- "Kardeş Kentleri Listesi ve 5 Mayıs Avrupa Günü Kutlaması [via WaybackMachine.com]" (in Turkish). Ankara Büyükşehir Belediyesi - Tüm Hakları Saklıdır. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- "Twinning Cities: International Relations" (PDF). Municipality of Tirana. www.tirana.gov.al. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-10. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- Twinning Cities: International Relations. Municipality of Tirana. www.tirana.gov.al. Retrieved on 2008-01-25.

- "Kardeş Şehirler". bursa.bel.tr (in Turkish). Bursa. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- "Des Moines to Become Sister Cities with Pristina, Kosovo". dsmpartnership.com. Greater Des Moines Partnership. 2018-11-09. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- "Relations Internationales". namurinternational.be (in French). Namur. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- "Statistical Yearbook of the City of Zagreb 2018" (PDF). zagreb.hr. Zagreb. p. 33. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

External links

- Municipality of Pristina – Official Website

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 361.

.jpg.webp)