Progressive dispensationalism

In Evangelical Christian theology, progressive dispensationalism is a variation of traditional dispensationalism.[1] All dispensationalists view the dispensations as chronologically successive. Progressive dispensationalists, in addition to viewing the dispensations as chronologically successive, also view the dispensations as progressive stages in salvation history.[2] The term "progressive" comes from the concept of an interrelationship or progression between the dispensations. Progressive dispensationalism is not related to any social or political use of the term progressive, such as progressive Christianity.

Development

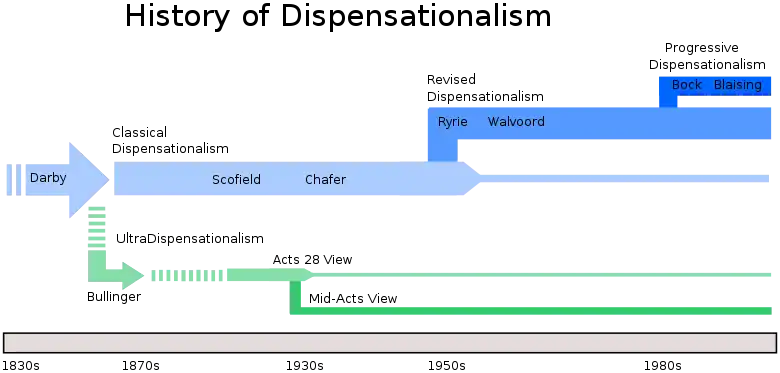

While elements of progressive dispensational views were present in earlier dispensational writers, including Scofield and Eric Sauer, the view itself coalesced around specific issues and questions raised in the 1980s. Numerous dispensational scholars came to a rough consensus and in the early 1990s produced three main books articulating progressive dispensationalist views.[3][4][5] Consequently, the editors and authors of the books - Craig A. Blaising, Darrell L. Bock, and Robert L. Saucy— are considered the primary spokespersons for progressive dispensationalism.

Comparison with traditional dispensationalism

Progressive and traditional dispensationalists hold to many common beliefs, including views that are uniquely dispensational. The vast majority of adherents in both schools hold to a distinction between Israel and the Church,[6] a future pre-tribulation rapture,[7] a seven-year tribulation, and a Millennial Kingdom [8] in which the rule of Jesus Christ will be centered in Jerusalem. Progressive dispensationalists tend to de-emphasize the pre-tribulation rapture doctrine, and some lean toward the post-tribulation rapture position.

The major difference between traditional and progressive dispensationalism is in how each views the relationship of the present dispensation to the past and future dispensations. Traditional dispensationalists perceive the present age of grace to be a "parenthesis" or "intercalation" God's plans.[9] In general, the concept means God's revealed plans concerning Israel from the previous dispensation has been "put on hold" until it resumes again after the rapture.

"Progressive" relationship between the covenants

Progressive dispensationalists perceive a closer relationship between the Old Covenant and the New Covenant than do most traditional dispensationalists. One of the covenants which highlight the differences between the two views is the New Covenant. In the past, dispensationalists have had a variety of views with regard to the new covenant. Some dispensationalists, including Charles Ryrie and John F. Walvoord in the 1950s, argued for two new covenants: one new covenant for the Church and another new covenant for Israel. Other dispensationalists, including John Nelson Darby and John Master, argued for one new covenant applied only to Israel. And still other dispensationalists, including Cyrus I. Scofield and John McGahey in the 1950s, have argued for one new covenant for a believing Israel today and an ongoing partial fulfillment, and another new covenant for a future believing Israel when Jesus returns for a complete fulfillment.

Progressive dispensationalists, like Blaising and Bock, argue for one new covenant with an ongoing partial fulfillment and a future complete fulfillment for Israel. Progressives hold that the new covenant was inaugurated by Christ at the Last Supper. Progressives hold that while there are aspects of the new covenant currently being fulfilled, there is yet to be a final and complete fulfillment of the new covenant in the future. This concept is sometimes referred to as an "already-but-not-yet" fulfillment.

Hermeneutics

Both traditional and progressive dispensationalists share the same historical-grammatical method. As with all dispensationalists, progressive revelation is emphasized so that the dispensationalist interprets the Old Testament in such a way as to retain the original meaning and audience. Thus progressives and traditionalists alike place great emphasis on the original meaning and audience of the text. The primary differences in hermeneutics between traditionalists and progressives are that progressives are more apt to see partial or ongoing fulfillment, and progressives are more apt to utilize complementary hermeneutics.

These differences between traditionalists and progressives show up in how one views the Old Testament texts and promises in the New Testament and how they are handled by the New Testament writers. For traditionalists, who perceive the present dispensation as a parenthesis, the standard approach has been to view Old Testament quotations in the New Testament as applications rather than fulfillment. If an Old Testament quotation is said to have a fulfillment role in the New Testament (outside of the gospels), then that may imply that the present dispensation is no longer a parenthesis, but has a relationship or connection with the prior dispensation. In contrast, progressives, instead of approaching all Old Testament quotations in the New Testament as application, attempt to take into account the context and grammatical-historical features of both Old Testament and New Testament texts. An Old Testament quote in the New Testament might turn out to be an application, but it also might be a partial fulfillment or a complete fulfillment or even something else.

As a framework for biblical interpretation, covenant theology stands in contrast to dispensationalism in regard to the relationship between the Old Covenant with national Israel and the New Covenant in Christ's blood.

Complementary hermeneutics

Complementary hermeneutics means that previous revelation (such as the Old Testament) has an added or expanded meaning alongside the original meaning. For example, in Jeremiah 31:31–34, the original recipients of the new covenant were Jews—i.e., "the house of Israel and the house of Judah." Progressives hold that in Acts 2, believing Jews first participated in the new covenant based on Jer 31:31–34. Gentiles were not named as original participants. However, additional revelation came in Acts 9–10 concerning believing Gentiles where God (through Peter and Cornelius) formally accepted believing Gentiles as co-heirs with the Jews. In other words, God used additional New Testament revelation to further expand the participants of the new covenant to include believing Gentiles. God did not replace the original recipients or change the original meaning of the new covenant, He simply expanded it. This expansion of meaning while keeping the original intact is what is called complementary hermeneutics.

Charles Ryrie

Charles Ryrie had also laid less stress on the parenthetical nature of the age of the Church. The restatement of the "parenthesis" comes from the nature of the Church as the mystery, previously not known and now revealed, that Jews and Gentiles are united in one body (Eph. 3:1-7). Although Ryrie opposed some of the tenets of progressive dispensationalism, he also advanced in the late 1970s, many years prior to the progressive movement, something very similar to complementary hermeneutics, particularly in his interpretation of the new covenant which he held was one new covenant that had successive (complementary?) applications to different groups of believers. In other parts of the world, outside of the United States, dispensationalists had also laid a strong emphasis on the present aspect of the Kingdom of God (cp. Other revisionist, like Emilio Antonio Núñez, in Guatemala, who was also a theological heir of Ryrie).

Recommended book list

- Bateman, Herbert W (1999). Three Central Issues in Contemporary Dispensationalism: A Comparison of Traditional and Progressive Views. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications. ISBN 0-8254-2062-8.

- Bigalke Jr., Ron J., "Progressive Dispensationalism." University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-7618-3298-X

- Blaising, Craig A.; Darrell L. Bock (1992). Dispensationalism, Israel and the Church: The Search for Definition. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Pub. House. ISBN 0-310-34611-8.

- Blaising, Craig A.; Darrell L. Bock (1993). Progressive Dispensationalism. Wheaton, IL: BridgePoint. ISBN 1-56476-138-X.

- Campbell, Donald K.; Jeffrey L. Townsend (1992). A Case for Premillennialism: A New Consensus. Chicago: Moody. ISBN 0-8024-0899-0.

- Dyer, Charles H.; Roy B Zuck; Donald K Campbell (1994). Integrity of Heart and Skillfulness of Hands: Biblical and Leadership Studies in Honor of Donald K. Campbell. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books.

- Feinberg, John S. (1988). Continuity and Discontinuity: Perspectives on the Relationship Between the Old and New Testaments; Essays in Honor of S. Lewis Johnson, Jr. Westchester, Ill.: Crossway Books. ISBN 0-89107-468-6.

- Henzel, Ronald M. (2003). Darby, Dualism, and the Decline of Dispensationalism: Reassessing the Nineteenth-century Roots of a Twentieth-century Prophetic Movement for the Twenty-first Century. Tucson, Ariz.: Fenestra Books. ISBN 1-58736-133-7.

- Hoch, Carl B (1995). All Things New: The Significance of Newness for Biblical Theology. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books. ISBN 0-8010-2048-4.

- Mangum, R. Todd (2002). The Falling Out Between Dispensationalism and Covenant Theology: A Historical and Theological Analysis of Controversies Between Dispensationalists and Covenant Theologians from 1936 to 1944. 2002.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Ryrie, Charles Caldwell, "Dispensationalism Today". Moody Press, 1965. ISBN 0-8024-2256-X

- Saucy, Robert L (1993). The Case for Progressive Dispensationalism: The Interface Between Dispensational & Non-Dispensational Theology. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan. ISBN 0-310-30441-5.

- Stauffer, Douglas D (1989). One Book Rightly Divided: The Key to Understanding the Bible. Millbrook, Alabama.: McCowen Mills Publishers. ISBN 0-9677016-1-9.

See also

- Christian eschatology

- Christian Zionism

- Covenant theology (opposing hermeneutical framework)

- Dispensationalism

- Historical-grammatical method of interpretation

- New Covenant Theology (attempted synthesis of classical covenantalism and dispensationalism)

References

- Bateman, Herbert W (1999). Three Central Issues in Contemporary Dispensationalism: A Comparison of Traditional and Progressive Views. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications. p. 309. ISBN 0-8254-2062-8.

- Blaising, Craig A.; Darrell L. Bock (1993). Progressive Dispensationalism. Wheaton, IL: BridgePoint. p. 127. ISBN 1-56476-138-X.

- Blaising, Craig A.; Darrell L. Bock (1992). Dispensationalism, Israel and the Church: The Search for Definition. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Pub. House. ISBN 0-310-34611-8.

- Blaising, Craig A.; Darrell L. Bock (1993). Progressive Dispensationalism. Wheaton, IL: BridgePoint. ISBN 1-56476-138-X.

- Saucy, Robert L (1993). The Case for Progressive Dispensationalism: The Interface Between Dispensational & Non-Dispensational Theology. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan. ISBN 0-310-30441-5.

- Blaising, Craig A.; Darrell L. Bock (1993). Progressive Dispensationalism. Wheaton, IL: BridgePoint. pp. 49–51. ISBN 1-56476-138-X.

- Blaising, Craig A.; Darrell L. Bock (1993). Progressive Dispensationalism. Wheaton, IL: BridgePoint. p. 317. ISBN 1-56476-138-X.

- Blaising, Craig A.; Darrell L. Bock (1993). Progressive Dispensationalism. Wheaton, IL: BridgePoint. pp. 54–56. ISBN 1-56476-138-X.

- Blaising, Craig A.; Bock, Darrell L. (1993). Bateman, Herbert W. IV (ed.). Progressive Dispensationalism. Wheaton, IL: BridgePoint. p. 33. ISBN 1-56476-138-X. Retrieved January 29, 2021.