Pyramid of the Moon

The Pyramid of the Moon is the second largest pyramid in modern-day San Juan Teotihuacán, Mexico, after the Pyramid of the Sun. It is located in the western part of the ancient city of Teotihuacan and mimics the contours of the mountain Cerro Gordo, just north of the site. Cerro Gordo may have been called Tenan, which in Nahuatl, means "mother or protective stone." The Pyramid of the Moon covers a structure older than the Pyramid of the Sun which existed prior to 200 AD.

Pyramid of the Moon | |

| Location | Mexico State |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesoamerica |

| Type | Pyramid, Temple |

| Part of | Teotihuacan |

| History | |

| Periods | Mesoamerican classic |

| Cultures | Teotihuacan |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Protected by UNESCO |

| Ownership | Cultural heritage |

| Management | World Heritage Committee |

| Public access | Yes |

The Pyramid's construction between 100 and 450 AD completed the bilateral symmetry of the temple complex.[1] The pyramid is located at the end of the Avenue of the Dead, connected by a staircase, and was used as a stage for performing ritual sacrifices of animals and humans upon. It was also a burial ground for sacrificial victims. These burials were done in order to legitimize the addition of another pyramid layer over the existing one. The passing of several rulers, and rapid changes in ideologies, led to the Pyramid of the Moon's exponential expansion between 250 and 400 AD. A platform atop the pyramid was used to conduct ceremonies in honor of the Great Goddess of Teotihuacan, the goddess of water, fertility, the earth, and even creation itself. This platform and the sculpture found at the pyramid's bottom are thus dedicated to The Great Goddess.

Opposite the Great Goddess's altar is the Plaza of the Moon. The Plaza contains a central altar and an original construction with internal divisions, consisting of four rectangular and diagonal bodies that formed what is known as the "Teotihuacan Cross."

Background and history

Between 150 BC and 500 AD, a Mesoamerican culture built a flourishing metropolis on a plateau about 22 km2 (8.5 sq mi). The ethnicity of the inhabitants of Teotihuacan is a subject of debate, therefore "Teotihuacan" is the name used to refer to both the civilization and the capital city of these people.[2] Teotihuacan was a highly influential civilization in Mesoamerica. The city was home to a religious complex which was the religious center of all of Mesoamerica. The people who lived there constructed a city conducive to religious life and worship by incorporating cosmology into every aspect of the urban plan.

During the initial phase of Teotihuacan, called Tzacualli (0–150 AD), ingenious building systems were developed to erect the monumental bases of the Pyramids of the Moon and the Sun. The Teotihuacan metropolis has a planified urbanization with main axis, and a huge palace surrounded by 15 monumental pyramids. It was said by the Aztecs to have been surmounted by a huge stone figure related to the moon. This figure was uncovered (weighing 22 metric tons and was somehow lifted to the top of the pyramid) and it represents the Great Goddess as a water deity.[3] Scholars have suggested that the water that flows through her hands is living water and represents a life-giving force and fertility.

Beginning in 1998, archaeologists excavated beneath the Pyramid of the Moon. Tunnels dug into the structure have revealed that the pyramid underwent at least six renovations; each new addition was larger and covered the previous structure.

As the archaeologists burrowed through the layers of the pyramid, they discovered artifacts that provide the beginning of a timeline to the history of Teotihuacan. In 1999, a team led by Saburo Sugiyama, associate professor at Aichi Prefectural University in Japan and adjunct faculty at Arizona State University,[4] and Ruben Cabrera of Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History, found a tomb apparently made to dedicate the fifth phase of construction. It contains four human skeletons, animal bones, jewelry, obsidian blades, and a wide variety of other offerings. Archeologists estimated that the burial occurred between 100 and 200 AD.

Another tomb dedicated to The Great Goddess was discovered in 1998. It is dated to the fourth stage of construction. It contained a single human male sacrificial victim as well as a wolf, jaguar, puma, serpent, bird skeletons, and more than 400 other relics which include a large greenston and obsidian figurines, ceremonial knives, and spear points.

Architecture

Basic structure

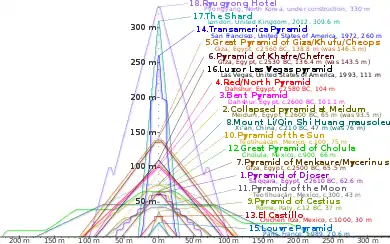

The pyramid is shaped like many of the other pyramids of Mesoamerica. The outer layer of the pyramid, which is currently visible features a talud-tablero shape.[2] It has 7 layers of buildings built on top of each other. It is 43 meters tall. Its base is 147 meters in the West to East direction by about 130 meters in the North to South direction. Given the name and contents of the pyramid, it is hypothesized that there the symbolism of the moon may have been associated with water, the rainy season, femininity, fertility, and even earth.

Placement

Among Mesoamerican cultures it is common to use the urban planning of their city to echo their cosmological and mythological beliefs regarding the order of the universe. The positioning of this pyramid plays into the narrative of Teotihuacan.[5]

The Pyramid of the Moon was deliberately placed at the end of the Avenue of the Dead and at the foot of Cerro Gordo.[5] This central position makes the processional nature of the Walk of the Dead rather clear. This mimicking of natural structures in human temples has been seen throughout Mesoamerican culture. The relation between the mountain, pyramid, and road has been theorized to resemble a connection between the road and the watery underworld, whereas the mountain serves as a sort of anchor to the earth. Also significant in the larger plan of the city is the orientation of all of the buildings. The north–south axis of the city emphasizes the cosmological and astrological ideologies of the city, since there was a connection between this orientation and the ritual 260-day calendar. The east–west was the worldly structure of the city used for the sake of symmetry. Connecting the Pyramid to the Avenue of the Dead is a public plaza, located at the base of the pyramid.[6] This plaza was viewed as the ritual/sacred site, while the pyramid was seen as a structure built on top of it.

Building layers

This pyramid has 7 different layers of buildings which were constructed on top of each other in order to update the building's religious power over time. Building 1 is the oldest monument in Teotihuacan, from approximately 100 CE. The structure was a square pyramidal platform with talud side facades that were about 23.5 meters long. Building 2 was a minor enlargement that covered the entire previous structure, while correcting its orientation, which was slightly unaligned from the true east–west axis of the Pyramid of the Moon Complex. Building 2 was also in talud style whose east–west walls were about 29.3 meters long. Building 3 covered the construction before it, but didn't expand much. Building 4: was a substantial enlargement which rendered the building's east–west width is 89.2 meters and its north–south length is 88.9 meters. This building was completed in approximately 250 CE. Building 5 was somewhat expanded, the architectural style of the building was the main shift. The east–west size didn't change, but the north–south wall grew to 104 meters. The style used was talud-tablero on both the main body and an additional adosada platform. This design still used the pyramid as a stage for ritual, rather than a house for a temple. Building 6 grew to be east–west 144 meters while north–south remained the same. This building was constructed to contain Burials 5 and 4 in approximately 350 CE. Building 7 is the final structure, which is still visible today, but was built in about 400 CE. A distinct shift in architectural style between the first three buildings may be indicative of an ideological shift.[6]

Function

Ritual sacrifice

This pyramid had several religious functions. The main function of the pyramid was public ritual sacrifice. Archaeologists have found a great number of sacrificed remains in the foundations of the pyramid.[5] Among the sacrificial victims were felines, birds of prey, snakes, humans, and more. These sacrifices can be carefully cataloged and examined when looking at the different burials within the different layers of buildings. Thus far, archaeologists have found a total of 5 rectangular burial offering complexes within the 7 layers of the pyramid. Sacrificial and inanimate offerings were carefully selected to represent large ideas of Teotihuacan cosmology (such as authority, militarism, human and animal sacrifice, femininity) rather than the worship of a single ruler or deity.[6]

Burials

Within the seven layers that make up the Pyramid of the Moon, there are five burial complexes labeled two through six. They were found to have contained sacrificial victims and other remains such as figurines, obsidian objects, as well as nonhuman animal remains. While the pyramid structures are labeled from the earliest to the oldest (one through seven), the burial structures are numbered in the order in which they were found (two through six). For example, burial two and six are associated with the time of the fourth structure, three with the fifth structure, and four and five with the sixth structure.[7] It is important to note that there have been no associated burials within structures one through three. The burials begin in conjunction with structure four. Due to this, Siguyama suggests a large-scale change politically and militaristically within Teotihuacan during the period of which structure four was built. This is because of the substantial increase in size of structure four, as well as the addition of ritualistic burials that correlate to the addition of new structures to the Pyramid of the Moon.[8]

Burial two was built during the construction of Building four and was believed to be built around 250 AD. It contained a single-seated corpse of a man facing west who was probably around 40–50 years of age. The structure also contained part of a different person's occipital bone. The first individual had offerings associated with him such as ear flares, beads, and a pendant. This would suggest that he was of relatively high status. Also, within the pit, their other offerings. First, there were several assortments of figurines depicting a human, blades of obsidian, and shells. The offerings were displayed so that the figurines had the obsidian blades pointing towards their heads. There were also storm god vessels that were placed near each corner of the burial pit. Finally, there was another figure of greenstone, probably depicting a female instead of a male. This is significant because many of the figurines were either not depicted as a clear gender, or were male. Scholars have suggested that this female figure may represent the goddess to which the ritual was being made.[9] Adding to this, there were nonhuman sacrifices as well such as pumas, eagles, falcons, crows, owls, rattlesnakes, and mollusks. The individual found, and his positioning suggests that he was probably bound before he was thrown into the grave hole. Studies on oxygen-isotope and strontium-isotope ratios within tooth enamel and bone were done by White and his team in order to determine possible locations of origin. Their work has revealed that the full skeleton was probably not originally from Teotihuacan, which could suggest that he was a sacrificial victim of war.[8]

Burial three is associated with structure five, and dates to approximately 300 A.D. In this chamber, there are a total of four people, who are all male. The first individual was thought to be about 20–24 years old, the second 18–20, the third 40–44, the fourth 13–15, all of whom were probably foreign to Teotihuacan. There are signs that the individuals had been tied and bound within the pit, suggesting again that they were possible captives. Associated with burial three there were other fibers found that may indicate that there was once a mat. Mats have been discovered to signify political authority in many Mesoamerican societies during the time. Adding to this, there were figures of greenstone, beads, shells, and blades. There were also ear flares and beads that suggested that at least three of the individuals were of high status. There were also a total of 18 decapitated heads of wolves, pumas, a jaguar, and a hawk.[8]

Burial four was made in conjunction with structure six and dates to around 350 – 400 A.D. The pit contained seventeen human heads that, from what could be identified, were middle aged males. Adding to this, burial four contained no offerings or material remains, other than the fibers from the material that was used to gag the victims. White has suggested that the placement of the skulls may have something to do with where they were originally from.[9] Due to the violent nature in which the victims where sacrificed, as well as the lack of burial offerings, it has been suggested that the individuals were of relatively low status.[8]

Burial five occurred at a similar time to burial four datings to around 350 – 400A.D and was also linked to the construction of building six. In it were three skeletons who were displayed in a position common in painted representations of Maya elites. This is interesting because it is an uncommon mode of burial at Teotihuacan. Adding to this, their hands were not bound but instead laying out in front of them resting on their legs. The first person was probably 50–75 years of age, the second 40–50, and the third 40–45. Adding to this, two individuals were wearing rectangular pectorals, which is often linked to high-ranking Mayas. Their burial suggests that these individuals were of extremely high status. The corpses were also accompanied by animals that may have represented their animal spirit, two pumas and a golden eagle.[8]

Lastly, burial six occurred within a similar time frame to burial three which coincided with the building of structure five around 300 A.D. There was a total of twelve skeletons found within this chamber and they all had their hands bound, once again suggesting that they were sacrificial victims. Two skeletons stood out as possibly being higher up in status, while the other ten were decapitated and seemed to be thrown about at random. Adding to this there were fragments of about 43 animals.[8]

Given the contents of these burials, Archaeologists, Leonardo Lopez Lujan and Saburo Sugiyama have theorized that they are possible cosmograms, representations of the heavens which were carefully laid out by priests according to predetermined patterns. Archaeologists also have concluded that human sacrifice to sanctify buildings was common throughout Mesoamerican time and geography[8]. In Teotihuacan, the preferred victims were sub-adult and adult males who were not from Teotihuacan, which differs from other structures at Teotihuacan. This could suggest that many of the sacrificial victims found at the Pyramid of the Moon were war captives. The animals used in the burials were all carefully selected, they included felines, canids, birds of prey, and rattlesnakes, all of which are carnivorous and can be associated with warfare[8]. Adding to this Siguyama has suggested heavily that sacrifice and large-scale construction correlate directly to the growth of state and military power.[10]

Other functions

The pyramid was also used for rituals other than sacrifices. Mesoamerican cities used plazas as the core of social life; in the case of the Pyramid of the Moon, the public plaza was also used for astronomical observation and calendar-related activities.[11] The complex contained small pyramidal structures, rooms, porticoes, patios, corridors, and low platforms. Moon plaza served as a supra-regional ceremonial, political and socioeconomic center.

Archeologists have examined the different layers of the pyramid and found a great number of these contained artifacts and remains which can be examined, and even presented to the public. Some of the artifacts found by archaeologists were made of greenstone, obsidian, and ceramic, all of which were carefully crafted in Teotihuacan. These artifacts included figurines and serpent knives.[6]

See also

- List of megalithic sites

- List of Mesoamerican pyramids

- Great Goddess of Teotihuacan

- Pyramid of the Sun

References

- Apromeci, Post Author (October 3, 2018). "Apromeci | Tzacualli Metztli (Pirámide de la Luna), Teotihuacan". Apromeci.

- Miller, Mary Ellen. 2012. Art of Mesoamerica: From Olmec to Aztec. London, UK: Thames & Hudson Australia P/l.

- Walker, Charles, 1980 Wonders of the Ancient World, pp. 150–3

- "Discoveries At Teotihuacan's Pyramid Of The Moon Help Unlock Mysteries Of Western Hemisphere's First Major Metropolis". ScienceDaily. Arizona State University, College Of Liberal Arts & Sciences. September 21, 1999.

- Cowgill, George L. (2016). Ancient Teotihuacan : early urbanism in Central Mexico. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521870337. OCLC 965908977.

- Robb, Matthew H. (ed.). Teotihuacan : city of water, city of fire. ISBN 9780520296558. OCLC 981118156.

- Spence, Michael; Periera, Grégory (2007). "The Human Skeletal Remains of the Moon Pyramid, Teotihuacan". Ancient Mesoamerica. 18 (1): 147–157. JSTOR 26309327.

- Sugiyama, Saburo; Leonardo, Luján (2007). "Dedicatory Burial/Offering Complexes at the Moon Pyramid, Teotihuacan: A Preliminary Report of 1998-2004 Explorations". Ancient Mesoamerica. 18 (1): 127–146. JSTOR 26309326.

- White, Christine (2007). "Residential Histories of the Human Sacrifices at the Moon Pyramid, Teotihuacan: Evidence from Oxygen and Strontium Isotopes". Ancient Mesoamerica. 18 (1): 159–172. JSTOR 26309328.

- Sugiyama, Saburo; Rubén, Castro (2007). "The Moon Pyramid Project and the Teotihuacan State Polity: A Brief Summary of the 1990-2004 Excavations". Ancient Mesoamerica. 18 (1): 109–125. JSTOR 26309325.

- Uriarte, Maria Teresa, ed. (2010). Pre-Columbian architecture in Mesoamerica. New York: Abbeville Press Publishers. ISBN 9780789210456.

External links

Media related to Pirámide de la Luna at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pirámide de la Luna at Wikimedia Commons