Rhys Caparn

Rhys Caparn (1909–1997) was an American sculptor known for her animal, landscape, and architectural subjects. Her works were mostly abstract but based on natural forms. In many of them she employed free lines and used a restrained style that nonetheless conveyed what critics saw as an emotional charge.[1][2] In the animal sculptures for which she became best known, she achieved what a critic called "a graceful curvilinear balance."[3] Another critic put this aspect of her style in terms of the arch of a cat's back in one of her pieces: "A cat's arched back is a pleasingly rounded shape and well balanced on the foundation of paws. But it is still a cat's back, embodying a cat's peculiar physical response to fear or affection."[2] Her foundational influences included an ancient Greek statue and the abstract works of Constantin Brancusi. From her most prominent instructor, Alexander Archipenko, she said she learned to seek out the underlying ideal in a natural form, the point at which "form and idea become one."[4] Her works were mostly small and almost all made by modeling.

Rhys Caparn | |

|---|---|

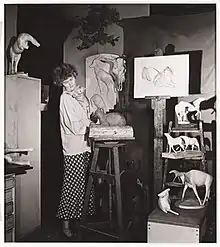

Rhys Caparn, in studio, 1948 | |

| Born | July 28, 1909 Onteora, New York |

| Died | April 29, 1997 (aged 87) |

| Known for | Artist |

She received her training in Paris and New York. With the support of her parents and two wealthy widows, she was able to devote her time to study and creative work and her sculptures made an immediate impact when first shown in the early 1930s. Throughout the rest of her long career, she exhibited frequently in commercial galleries, museums, and the shows of the nonprofit associations of which she was a member. She helped to form the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors in 1940 and thereafter served as one of its leaders. In the 1940s and 1950s, she taught sculpture classes two days a week at the Dalton School in Manhattan. She won a prestigious and controversial award from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1951. She died of Alzheimer's disease in 1997.

Early life and education

Caparn was born in 1909 in a resort town north of New York City. Her father was a noted landscape architect and her mother a successful voice teacher.[4] In 1926, during her senior year in a local private school, her mother brought her to France for a visit with her sister Anne who was studying in Paris. During a visit to the Louvre, Caparn encountered an ancient sculpture, a kore of a young female acolyte from the Heraion of Samos. The sculpture is a standing figure missing its head wearing traditional garments with almost no body parts exposed. The piece has been described as a subtle handling of the layered fabrics' lines and folds.[5] Caparn later said it became a major influence in shaping her approach to art.[6]

After graduating from high school, she spent two years as a student in Bryn Mawr College where an art history course in ancient Greek sculpture captured her attention.[6] Her realization that a four-year liberal arts education was not for her coincided with a minor crisis in the life of her older sister, Anne.[6][note 1] Despite the stock market crash of 1929, their mother found money enough for the two sisters to spend a year in Paris.[6] Once there, Caparn began studies under an animal sculptor, Édouard Navellier, at the École Artistique des Animaux.[8][note 2] She later recalled that the school maintained a menagerie including a wild boar. The boar, she said, was tame in comparison with a savage goose that was also present.[11] Returning home at the end of 1930 she took a further two and a half years of instruction from the avant-garde sculptor Alexander Archipenko in his school in Manhattan.[6][12][note 3] She sculpted human torsos during this period but soon realized that she preferred animal forms. She began going to the Bronx Zoo and for the next two years made many drawings of animals.[6]

Caparn later credited two women with the guidance and financial aid she needed to complete her studies and embark on a career as a professional sculptor. The first was Elizabeth Alexander, widow of the painter John White Alexander. Elizabeth Alexander helped make Caparn's time in Paris "the most wonderful year in the world" by giving her and her sister a place to live, by finding studio space for her to work in, by arranging for her to study with Navellier, and, later, by encouraging her to attend classes with Archipenko.[6][note 4] The second woman was Lee Wood Haggin (1856–1934). Like Alexander, Lee Wood Haggin was a wealthy widow whose philanthropy contributed to New York culture in general and to artists in particular. Both women were connected to the MacDowell Club. Haggin was its founder and leading financial supporter and Alexander was active in its affairs.[16] They were both residents of Onteora, the private community where Caparn was born.[17][18] Caparn later said of Haggin, "Mrs. Haggin helped me a great deal, simply because of the kind of person she was."[6][note 5]

Career in art

Caparn's first exhibition took place in 1932 a few days before her twenty-third birthday. It was held in conjunction with a concert by baritone Willard Fry held at the Southampton studio of his uncle the artist, Marshal Fry. She showed human and animal figures in marble, clay, and terracotta and the New York Times covered the event in its Society pages.[19] The following year she was given an exhibition with two other artists at a commercial New York gallery called Delphic Studios.[note 6] Reviewing the show in the New York Sun, critic Henry McBride said she used "the freest lines for forms" to make emotionally charged works to which "the old-fashioned ideas of sculpture do not apply."[1] Archipenko contributed an introduction to the Delphic Studios catalog for the exhibition. In it he wrote, "The idealism of Rhys Caparn and her love for the spiritual permit her to create a new form of sculpture, without her losing the ability to sculpt in a naturalistic form when she so desires."[23] Also in 1933, she made the animal forms that encircled an armillary sphere made by her father as part of his landscape design at the Brooklyn Botanical Garden.[24][25]

In 1935 Delphic Studios gave Caparn a solo exhibition in which she showed realist portrait heads as well as animal abstractions.[3] In this period her sculpture was not universally admired. When she participated in a group show sponsored by Salons of America in 1936, Anita Brenner of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle called attention to her "monstrous sculpture inspired by rubber tubes."[26][note 7] Late in the decade she received an invitation to join an outspoken group of extreme abstractionists called American Abstract Artists. She joined and remained a member but later said she was not particularly committed to the organization. She said it was not as collegial as the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors which she helped found in 1940.[6]

In 1939, Caparn contributed drawings to the annual black-and-white exhibition at Grant Studios.[28][note 8] This was the first time she showed her works on paper. She showed them frequently in later years, often in conjunction with her sculpture. In a 1967 interview she said, "I've drawn all my life. You draw for a vocabulary; it feeds your eye" and when, in 1983, an interviewer commented on her freedom of line, she said she drew spontaneously and very quickly.[6][31]

Later in 1939, Caparn participated in a group exhibition at the Passedoit Gallery.[28][32][note 9] In reviewing the show Howard Devree said, "Rhys Caparn's 'Bird' has about it more than a little of antique Chinese abstraction of treatment and her 'Stalking Cat' compasses sinister stealth."[32] In 1942 Caparn exhibited sculptures of animals from countries then at war at an exhibition held at the Bronx Zoo, made posters supporting the war effort, and participated in a fund-raising event called "Women Can Take It."[33][34][35][note 10]

In 1944 Caparn was elected president of the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors (the organization she had helped to found four years earlier). In that role she wrote the Museum of Modern Art to take issue with what she called its "increasingly reactionary policies" toward the work of American artists.[4] In February of that year the Wildenstein Gallery gave a one-person show of her animal sculptures and drawings. Reviewing the show, a critic for the New York Times said, "The true spirit of all these animals has been caught."[37] At the same time Naomi Jolles of the New York Post interviewed Caparn regarding her life and work. In the interview she said she saw her work was an extension of her life and added her regret that people tended to see art as something separate from the daily lives they led.[11]

Caparn began part-time work as an art instructor in 1946. Over the next 25 years, she taught classes two days a week at the Dalton School, a private school in Manhattan. She later said she was surprised how much she enjoyed the work and surprised as well that she was good at it.[31] In 1947 she served on a jury of the National Association of Women Artists to select works for an exhibition at the National Academy of Design. When the president of the association removed a sculpture called "The Lovers," Caparn resigned. She resumed her membership after the piece was re-installed following an apology from the president for what she said was a misunderstanding.[38] Later that year she showed animal subjects in a solo exhibition at Wildenstein Galleries, including a group called "White Stallions" and a single piece called "Doe" that Devree said were among the best things she had done.[39]

The year after that she accompanied her husband on a trip to countries behind what was then being called the Iron Curtain and after her return began, for the first time, to sculpt landscape forms.[40] A few years later she was one of eleven sculptors to represent the United States in a competition held in London on the subject, "The Unknown Political Prisoner." The piece she presented, an abstract standing figure, did not win the award, but was nonetheless pictured in a New York Times article on the event.[41] In 1956 she was given the first of several solo and group exhibitions at the Meltzer Gallery.[42][note 11] Calling her work "semi-abstract," a critic said, "her feeling is exclusively sculptural and has nothing to do with illustration or literary values."[42] A retrospective solo exhibition at Meltzer three years later drew from Stuart Preston of the New York Times a summation of her approach. He said the sculpture was formal but also expressive and abstract but with "acute individual characterization." He said she discarded the "trivia of realism in order to concentrate on her subject's ultimate shapes."[2] When in 1958 she showed with two other sculptors at the American Museum of Natural History Preston wrote that "Rhys Caparn's carvings catch [her subjects] at fugitive moments, birds flying, gazelles leaping or horses rearing. Quick observation and a feeling for grace of movement are at work here."[44] Similarly, when she showed landforms at a solo show of recent bronzes at Meltzer in 1960, Preston noted that the pieces stood "proxy for observed landscape."[45] Later that year her sculpture was included in a group show entitled "Aspect de al Sculpture Americaine" at the Galerie Claude Bernard, Paris. The following year she was given a retrospective solo exhibition at the Riverside Museum.[46][note 12]

During the 1950s and 1960s, Caparn continued to participate in group exhibitions held by the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors and the National Association of Women Artists. She moved home and studio to Connecticut in the middle of the 1960s and thereafter favored local commercial galleries for exhibitions. A gallery in Bethel, Connecticut, gave her a 47-year retrospective in 1977. Reviewing the show a critic for a local paper described architectural pieces that had not previously been noted, pointing to her use of "the sparsest elements—a single while wall and lintel of its portal, a couple of arches, a village square, a fragmented empty chapel."[40] Regarding a retrospective show in 1981 a critic for the New York Times wrote of landscape plaster reliefs that began to appear following her postwar trip to Eastern Europe and mentioned house shapes that had become a more recent preoccupation. This critic also mentioned a "gentle but firm touch" evident in her work and suggested, "it may be that she lacks that touch of megalomania so necessary for the effective statement in three dimensions."[49]

Prizes

Caparn received awards from the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors (later National Association of Women Artists), including its Medal of Honor for Sculpture.[46][50][51] In a national competition called "American Sculpture, 1951" at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Caparn's "Animal Form I" was awarded $2,500 as second prize. The National Sculpture Society complained that the jurors unjustly favored a modernist style over the classically realist style that it advocated. A letter from the society called the award-winning pieces "work not only of extreme modernistic and negative tendencies but mediocre left-wing work at that." The museum stood by its decisions and issued a statement defending the neutrality of its award policies.[40][52][note 13]

Artistic style

Caparn's earliest influences came from her encounter with the sculptures of ancient Greece.[6] As an art student she learned a realist technique from her Parisian art instructor, Édouard Navellier, and her early animal and figure pieces were correspondingly realist in style.[19] On returning to New York she attended an exhibition of works by Brancusi that, as she later said, completely changed her approach to art.[6][55] She began to develop a style that, in 1935, Howard Devree, called a "graceful, curvilinear balance."[3] This style was not symmetrical and ornamental, but rather expressive, with the ability to create an emotional response in the viewer. Writing in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1936, Anita Brenner told readers that "charm and decorative value" could not yield first-rate works of art; to accomplish that feat required the power of emotion. "As between an academician and a Goya, equally skilled," she said, "what makes the difference is the power of emotion in the Goya."[26] When, in response to an interviewer's question that year, Caparn called her work "expression with form," she was agreeing with this principle. In 1933, Henry McBride, writing in the New York Sun had compared the emotional effect she achieved with the response listeners feel in a musical performance.[1] She agreed with this point as well, saying, in 1936, that she believed sculpture and music to offer analogous emotional experiences. "Modernism in sculpture," she said, "is like music in form."[56] She was passionate about form but was not seen as a formalist, her style was spare and reserved while remaining expressive. One critic put this aspect of her style in terms of the arch of a cat's back: "A cat's arched back is a pleasingly rounded shape and well balanced on the foundation of paws. But it is still a cat's back, embodying a cat's peculiar physical response to fear or affection."[2] Caparn's sculptures, "Stalking Cat" (at right) and "Standing Bird" (at left) show her ability to create the expressive forms that critics saw in her work.

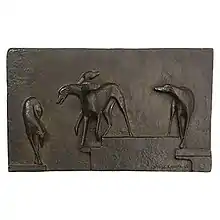

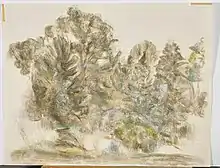

Caparn did not carve hard materials to make her sculptures. Rather than cutting away, she built up, modeling in soft materials such as clay, plasticine, plaster, variants of plaster (hydrocal and densite), and a material called "tattistone".[4][31][note 14] She made free-standing single subjects and subjects in groups as well as reliefs. Her works on paper were in black and white and pastel.[31] Almost all her pieces were small. Once, she said, she made a six-and-a-half-foot statue, adding, "It was fun, but too big. I couldn't move it out of the studio."[46] Caparn's sculpture, "The Bear," (shown at right) is larger than most of her work, but otherwise quite typical of her style. "Greyhounds" (shown at left) is an example of her work in relief. The drawing of foliage (shown at right) is an example of her work on paper. Its subject is reminiscent of her father's landscape photos and plans.

Personal life and family

Caparn was born on July 18, 1909, in a private resort called Onteora in New York's Catskill Mountains.[note 15] Caparn's father was Harold ap Rhys Caparn (1863–1945). A British immigrant, he was a successful landscape architect and author, known for his work in the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, the Bronx Zoo, the campus of Brooklyn College, and other public and private gardens.[61] Her mother was Clara Howard Jones (Royall) Caparn (1866–1970), a vocalist and successful voice teacher.[62] Clara Caparn began teaching soon after moving to Manhattan in the early 1900s and, using the professional name "Mrs. C. Howard Royall," succeeded in attracting students among the matrons of New York's social elite and their daughters. She also attracted talented, but less wealthy students and for their benefit frequently held performances to raise scholarship funds.[63] In 1939 she created "An Hour of Music," an organization that supported and encouraged young musicians by giving them opportunities to perform in public.[64] She taught until age 85 and died in 1970 at the age of 103.[8] Caparn's parents were married in Manhattan in 1906 after her mother had dissolved a marriage of 1889 to George Claiborne Royall (1860–1943), a merchant of Goldsboro, North Carolina.[65][66]

Caparn had an older sister, Anne Howard Caparn (1907–1971), with whom she was close.[6][8] She had two step-brothers from her mother's first marriage, Kenneth Claiborne Royall (1894–1971) and George Claiborne Royall, Jr. (1896–1967).[66] Both were raised by their father in Goldsboro, both attended the University of North Carolina, and both served as officers in the U.S. Army. The elder was a lawyer and general in the U.S. Army. Appointed Secretary of the Army in 1947, he oversaw the racial integration of the Army and Air Force. Having returned to private practice he was, in 1963, appointed co-leader of a commission to investigate white-supremicist violence in Birmingham, Alabama.[67] The younger saw service in France during World War I and retired as a Major. He was an investment banker in the 1920s and subsequently held positions in the federal government in Washington, D.C.[68][69]

As a child, Caparn enjoyed outdoor life on her family's rustic estate called Fernie Farm in Briarcliff Manor, New York. She later said her childhood ambition was to collect animals, adding that neighbors learned to call her parents when their pets disappeared.[11] A biographer of Caparn's said that in watching her father implement the landscape designs for the property, Caparn "became aware of her father's enthusiasm for designed space--the positive shape of a tree, the negative shape of the sky, the precise angle of a slope."[8] Although the family stayed at Fernie Farm only on weekends and during vacations, Caparn's parents were contributing members of the community. Giving the Briarcliff address as her residence, her mother was founder and president of the Art Alliance of Westchester County.[70] Her father was a member of the Briarcliff municipal board and designer of the village park.[17][71]

Caparn attended the Brearley School between 1918 and 1927. In 1925 and 1926 she took dance classes from Adeline King Robinson in preparation for her 1927 début in New York society.[72][73][note 16] Complying with social practices of the time, Caparn's mother hosted a series of luncheons in her honor at the Cosmopolitan Club.[73]

After graduating from Brearley, Caparn received a prize for academic excellence as a first-year Bryn Mawr student.[75] When, in 1929, the engagement of Caparn's sister Anne was broken off, and when, at the same time, Caparn decided that she did not wish to pursue her education at Bryn Mawr, their mother provided funds for the two women to spend a year in Paris.[6] It was then, as noted above, that she studied under Edouard Navellier.

In the early 1930s, after she had established herself as a professional sculptor, Caparn met her future husband, Johannes Steel (1908–1988). He had come to her studio to examine the sculpted head she had made of a mutual friend.[11] Although her mother would have liked to give the couple a society wedding, their marriage date was put forward after Steel received an unexpected foreign assignment and the couple departed for London very soon after the ceremony.[76] German-born, Steel came to the United States in 1934 and was naturalized in 1938. An outspoken critic of the Nazi regime, he earned his living as an author, journalist, lecturer, and radio commentator. After World War II, he was investigated and condemned for his Soviet sympathies. Late in life, he wrote news columns on the stock market. In the 1960s he served a year in prison for violating securities laws.[77][note 17] Through all the ups and downs of Steel's career, Caparn remained deeply attached to him, and he to her.[17] Steel died in 1988 at 80 years old. His obituary in the New York Times called him "a newspaperman and radio commentator whose career was marked by controversy over his outspoken left-wing views and his often sensational political and economic predictions."[77] In the mid-1960s, when Steel began writing for the News-Times of Danbury, Connecticut, he and Caparn moved first to the nearby community of Newtown and later lived in Danbury.[8] While living in Newtown and Danbury she would write occasional art comments for the same paper.[31]

She died in Danbury on April 29, 1997 of Alzheimer's disease.[8]

Notes

- In 1926 Anne Caparn spent a year studying in Paris. In 1927 she was active in New York society. In 1928 she became engaged to Theodore Lee Gaillard, a journalist working on the society pages of the New York Times. The minor crisis in Anne's life was Anne's termination of this engagement at some point during 1929.[6][7]

- Édouard Félicien Eugene Navellier (1865–1944) taught animal sculpture at the École Artistique des Animaux in Paris during the 1920s and 1930s. He exhibited widely and was well-known in Europe for his precise, realistic work.[9][10]

- Alexander Archipenko (1887–1964) opened an art school in Manhattan soon after his arrival from Berlin in 1923. He had previously directed art schools in Paris (1913) and Berlin (1921).[13] Called simply the Archipenko School, it gave instruction in sculpture, painting, and drawing.[14]

- Left wealthy at her husband's death in 1915, Elizabeth Alexander (whose maiden and married surnames were both Alexander) engaged a long and productive career as philanthropist in New York and cultural leader. A founder of the Arden Galleries, she was particularly noted for her ability to identify and assist young artists by providing direct financial support and by arranging benefit concerts and exhibitions to raise funds for their benefit.[15]

- Caparn's father, Harold ap Rhys Caparn, designed a cloister garden for Haggin's property at Onteora.[17]

- Journalist and art patron Alma Reed founded Delphic Studios in 1929. Mainly known for its emphasis on Mexican art, the gallery also showed photographers, such as Edward Weston and Ansel Adams as well as contemporary American artists, such as Thomas Hart Benton, and sculptors such as Gwen Lux.[20][21] In 1931 Reed had mounted an exhibition of Edward Weston's photographs at the Brooklyn Botanical Garden. The images were said to illustrate the use of plants as source material for design.[22]

- In 1922 Hamilton Easter Field founded Salons of America to give artists an alternative to the Society of Independent Artists whose financial and publicity methods he found objectionable. A reporter said he aimed "to give equal opportunity to every member, whether he or she be a conservative or a post-Dadaist."[27]

- Marion Louise MacDonald Grant (1895-1984) was a Canadian-born American citizen. She was the wife of financier Seaward Grant and a leader in Brooklyn society. In 1931 she established a commercial gallery called Grant Studios in Brooklyn Heights. The gallery showed contemporary American painters and sculptors, including many women. It was said to specialize in helping ignite the careers of struggling artists.[29] In addition to selling art, Grant made space available for social events and fund-raising events.[30]

- The Passedoit Gallery was founded by Georgette Passedoit. Born in Paris in 1875, she came to New York in 1892 and established a career as an actress. A goddaughter of the French commander, Joseph Joffre, she returned to France during World War I to care for wounded soldiers. After returning to New York and making a name for herself on the Broadway stage, she opened the Passedoit Gallery in 1932.

- "Women Can Take It" was the name of a benefit performance put on by New York artists and celebrities to raise funds for the Citizens Committee for the Army and Navy. That group put on stage shows at military installations. Caparn participated (under her married name) in a part of the show called "cavalcade of women of history."[35] "Women Can Take It" was also the name of a radio program that the Citizens Committee sponsored.[36]

- Doris Meltzer (1908–1977) opened the gallery that bore her name in 1955. A former director of the National Serigraph Society, she had previously operated the Serigraph Gallery at the same location. The Meltzer Gallery showed painters, printmakers, and sculptors, including many women artists.[43]

- Established in 1938 and closed in 1971, the Riverside Museum held exhibitions of modern art, particularly contemporary works by women artists and artists from Asia and Latin America.[47][48]

- The letter from the National Sculpture Society had been circulated widely across the United States asking recipients to endorse the protest. When submitted, it contained the signatures of 273 artists along with professionals in other fields. Its tone was distinctly political, purporting to speak "in the name of the sound, normal American people," it accused the museum of participating in a left-wing conspiracy and maintained that "American democracy" was being "attacked from every angle by a philosophy of totalitarianism" of which "modernistic art proved an effective vanguard."[52] The College Art Association, American Federation of Arts, American Institute of Architects, and other national organizations defended the Metropolitan Museum and criticized the sculpture society for conflating modern art and radical politics.[53][54]

- Like plaster, hydrocal and densite are derived from gypsum rock. They are both stronger than plaster, having greater density and being more crystalline. Densite is the stronger of the two.[57] Tattistone was an aggregate of marble dust, color, stone chips, and hardening agents that was made by the conservator, Alexander Tatti, for sculptor Louise Nevelson in the 1940s.[58]

- Onteora still exists with its original name and it remains a private seasonal community organized as a club. It was founded in 1887 by Candace Wheeler with her sister-in-law, Jeannette Thurber, and their husbands. Wheeler was an interior designer, author, and founder of the New York Society of Decorative Arts. Thurber was a patron of classical music and founder of the National Conservatory of Music of America. Consisting of rustic cottages and an equally rustic inn, called the Bear and Fox, the club required new members to be nominated and elected by current ones. In its early years, its members were mainly people in arts and letters, particularly single women within New York literary circles.[59] One visitor described Onteora as a "cottage colony for city dwellers in comfortable circumstances with a desire to retreat to the woods to meditate on art, nature and society."[60] Calvert Vaux, a landscape architect and associate of Caparn's father in the plans for the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens, was a director of Onteora. Jeannette Thurber, head of a music academy in Manhattan and likely acquaintance of Caparn's mother, was one of Onteora's founders.[60]

- Like many prospective debutantes, Caparn took classes from Robinson to learn how dance and perform her other duties gracefully during the events of the debutante season. Robinson also organized dances, known as Robinson alumnae dances, at places like the St. Regis, Ritz-Carlton and Plaza hotels for young women who had completed her classes.[74]

- Steel's birth name was Herbert Johannes Stahl. He was born and raised in Germany, became a minor official in a German economic ministry, and escaped the country after an arrest for publishing an article critical of the Nazi party. Thereafter, he used Johannes Steel as a pseudonym when writing anti-Nazi publications first in Great Britain, then in the United States. When he became a naturalized citizen some four years after his arrival in New York, he changed his surname to Steel. His legal name was then Herbert Johannes Steel and he used Johannes Steel as his professional name. (The German word "stahl" means "steel" in English.)[78] Throughout the 1930s he continued to write articles attacking the Nazi regime. In them, he frequently made predictions and became well known for the few that proved to be accurate. During these years and throughout the war years, Steel was a popular radio commentator, giving support to the New Deal policies of the Roosevelt government, its preparations for war, and the American contributions to the defeat of the Axis powers. He also voiced support for Soviet Communism and the Soviet military actions in Europe. During the early years of the Cold War, his warm regard for a regime that had now come to be seen as America's main enemy caused him to be investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee. At this time he also lost his job as radio commentator and transformed himself into a syndicated newspaper columnist on the New York stock markets. During the 1960s he served a year in federal prison after being convicted for selling unregistered stock in a company he controlled.[78]

References

- Henry McBride (1933-11-18). "Agreeable but Not Profound". New York Sun. New York, New York. p. 15.

In the Delphic Galleries three artists are exhibiting, Rhys Caparn. William Cooper and Ansel Adams. Rhys Caparn is a pupil of Archipenko, and like that explorer is willing to sail the uncharted seas. She uses the freest lines and forms, forms so free that the old-fashioned ideas of sculpture do not apply to them, and instead one is obliged to take them emotionally, like music. Mr. Archipenko says his pupil has a kinship to Chopin. At any rate she is free and unexpected in her effects.

- Stuart Preston (1959-11-01). "Of Past and Present". New York Times. New York, New York. p. X21.

In Rhys Caparn's animal bronzes dating from 1935, at the Meltzer Gallery, the artist's main effort is directed toward resolving natural forms into their basic elements. In this process she discards the trivia of realism in order to concentrate on her subject's ultimate shapes. However, this streamlining is as expressive as it is formal. A cat's arched back is a pleasingly rounded shape and well balanced on the foundation of paws. But it is still a cat's back, embodying a cat's peculiar physical response to fear or affection. The play between abstraction and acute individual characterization is the distinguishing feature of Miss Caparn's work.

- Howard Devree (1935-11-06). "A Reviewer's Week". New York Times. New York, New York. p. X8.

Rhys Caparn, whose work Mrs. Reed has exhibited before, has a maturing talent in decorative sculpture which depends considerably on graceful curvilinear balance: but it is doubtful if such titles as "Stratosphere" or "Parenthesis" contribute much. The portrait head of Miss Margaret Bayne is a characterful bit, effective if in more conventional vein.

- Jules Heller; Nancy G. Heller (19 December 2013). North American Women Artists of the Twentieth Century: A Biographical Dictionary. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0741480576.

- "Kore from the Cheramyes group". Louvre Museum, Paris. Retrieved 2020-07-05.

- "Oral history interview with Rhys Caparn, 1983 November 23". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- "Marriage Announcement". New York Times. New York, New York. 1928-04-08. p. N6.

- "Rhys Caparn — Artist Biography". Oliver Chamberlain on AskArt. December 2005. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

Materials assembled from the Caparn Family Collection of Oliver Chamberlain, Jr., cousin of Rhys Caparn.

- "Edouard Navellier". William Secord Gallery, inc. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- Naomi Jolles (1944-02-17). "Rhys Caparn Makes Even Stone Articulate". The New York Post. New York, New York.

- "Notes of Social Activities in New York and Elsewhere". New York Times. New York, New York. 1930-12-09. p. 35.

- "Biographical Note | A Finding Aid to the Alexander Archipenko papers, 1904-1986, bulk, 1930-1964". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- "Display Ad: Archipenko School". New York Times. New York, New York. 1930-06-01. p. E9.

- Sanka Knox (1947-01-16). "Mrs. J. Alexander, Arts Patron, Dead". New York Times. New York, New York. p. 25.

- John Sloan (12 July 2017). New York Scene: 1906-1913 John Sloan. Taylor & Francis. p. 592. ISBN 978-1-351-50304-4.

- Oliver Chamberlain (2013). Landscapes and Writings of Harold Caparn. Infinity Publishing. ISBN 978-1-135-63889-4.

- "A Finding Aid to the John White Alexander papers, 1775-1968, bulk 1870-1915 | Digitized Collection". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2020-06-24.

- "Fry Gives Recital in Southampton". New York Times. New York, New York. 1932-07-22. p. 12.

- "Artists Biographies A-C - WPA Meets IUP : A Glimpse Into America's Artistic Past". LibGuides at Indiana University of PA. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- "Who's that Lady? | Alma Reed". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2020-06-09.

- "The Eight". Whitney Museum of American Art News. Brooklyn, New York: Brooklyn Botanic Garden. 21: 4–6. 1932. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- James Thomas Flexner (March 1998). Maverick's Progress: An Autobiography. Fordham Univ Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-8232-1661-1.

- "Signs of Zodiac - Armillary sphere, Brooklyn Botanic Garden - New York". Signs of Zodiac on Waymarking.com. Retrieved 2020-06-09.

- "Harold ap Rhys Caparn". The Cultural Landscape Foundation. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- Anita Brenner (1936-05-10). "The Spring Art Season Draws to a Close". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. p. C12.

DEPRESSING note for the end of the season, to neutralize the chirping birds and the nodding daffodils, the Salons of America show. It is a kind of Independents, without the excitement. The boys and girls of the art press made its rounds unanimously unhappy. There are eight or ten things, out of over 200, that do not set your teeth on edge. Names, Walter Sarff, Anne Eisner, Wood Gaylor, Dorothea Greenbaum, and we may have unjustly forgotten three or four others. On the other hand, who, faced with Rhys Caparn's monstrous sculpture inspired in rubber tubes, can remember not to forget, unfairly, anything? Ah! These are the conscientious experiences that leave your critics, at the end of the season, suffering from shock, It is like a hangover, and the treatment is the same.

- "Salons of America a New Art Society". The New York Times. 1922-07-03. p. 12.

- Howard Devree (1939-01-15). "A Reviewer's Notebook". New York Times. New York, New York. p. X10.

... drawings by Rhys Caparn which reveal the sculptor's spatial sense.

- Elizabeth C. Tazelaar (1932-04-03). "Brooklyn Art Center Fills Esthetic Need; Grant Studios Haven for Artists, Esthetes, and Just Lay Public". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. p. 78.

- "Mrs. Seaward Grant to Open Studio Here". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. 1931-03-22. p. 11.

Mrs. Seaward Grant of 334 E. 17th St. is the latest society woman to go into business. Mrs. Grant has taken the old Whitney house at 114 Remsen St. and will convert it into the Marion Grant Studios, where Brooklyn and Manhattan artists and art societies may exhibit their works. At the same time May Grant will open the lower floors of the house for private teas, receptions, card parties and contract bridge classes. In establishing the studios she is expanding a program begun in her Flatbush home last November when an artist friend brought to her attention the difficulties artists have in getting suitable galleries and at the same time a "public."

- Linette Burton (1967-08-23). "Animal Sculptor Rhys Caparn to Have Show, Sale, August 27". Bulletin. Wilton, Connecticut. p. 5.

- Howard Devree (1939-12-31). "A Reviewer's Notebook". New York Times. New York, New York. p. 94.

Rhys Caparn's "Bird" has about it more than a little of antique Chinese abstraction of treatment and her "Stalking Cat" compasses sinister stealth.

- "Zoo to Open Art Exhibit". New York Times. New York, New York. 1942-01-15. p. 17.

- "Artists Aiding in War Effort". New York Times. New York, New York. 1942-02-22. p. X9.

- "Show to Depict Women in War". New York Times. New York, New York. 1942-11-22. p. D2.

- "Mrs. G. Blakeslee, Aided Service Men". New York Times. New York, New York. 1953-12-25. p. 17.

In 1942 Mrs. Blakeslee, who then was married to David Bundler, an attorney, conceived the idea of a radio program devoted to the activities and needs of women in war-time jobs. The program, named "Women Can Take It," was produced for several years over station WMCA. The following year Mrs. Blakeslee transferred the program to the Rivoli Theatre, where it was produced as a revue for as one-night benefit performance.

- Edward Alden Jewell (1944-02-09). "French Art Show at Wildenstein's". New York Times. New York, New York. p. 17.

Most of her subjects are animals and birds. There is the splendid "Stalking Cat." There is a "Wild Ox," powerfully and vividly fashioned . There s the "Antelope" standing, its head stretched down to the ground. Three "Wild Cattle" form a well-designed group. The true spirit of all these animals has been caught. The several birds are strange and the sculptor has injected a strong element of fantasy. Portraits include admirable heads of Johannes Steel, done in 1935, and of Jimmie Savo (1943; lent by Mrs. Robert M. Moore Jr)

- Sanka Knox (1947-04-26). ""Lovers," Prize Winning Sculpture, Barred From Academy Art Show". New York Times. New York, New York. p. 1.

- Howard Devree (1947-10-12). "By Groups and Singly". New York Times. New York, New York. p. X9.

- Martha B. Scott (1977-06-12). "Rhys Caparn's Environments: Captivating in Their Simplicity". Bridgeport Post. Bridgeport, Connecticut. p. 75.

If in the end her art is not too memorable, it may be that she lacks that touch of megalomania so necessary for the effective statement in three dimensions.

- Aline B. Louchheim (1953-01-28). "11 Sculptors Will Represent U. S. At International Contest in London: Models of Their Entries Being Placed on Exhibition at Modern Art Museum". New York Times. New York, New York. p. 29.

One of the more realistic models is a single, highly simplified standing figure by Rhys Caparn.

- "About Art and Artists: Rhys Caparn's Sculpture at Meltzer's Confirms Her Naturalist Creed". New York Times. New York, New York. 1956-01-21. p. 19.

She is a naturalist, very conscious of the bone beneath the skin and adapting its suggestions to her own spare and reserved style. Her inventiveness lies in the way in which she combines these forms into elaborate constructions of interweaving planes, as in a giant and grotesque seashell. Even in some of the over-elaborate pieces, which tend to be heavy and glum, we are conscious that her feeling is exclusively sculptural and has nothing to do with illustration or literary values. Her smaller animal studies, though still projections of her own manner, contain. none the less, many hints of characteristic animal spirits.

- "1955 Serigraph Gallery became the Doris Meltzer Gallery on 57th St". Nashville Banner. Nashville, Tennessee. 1955-04-29. p. 31.

- Stuart Preston (1958-04-06). "Birds, Beasts and Fish". New York Times. New York, New York. p. X10.

- Stuart Preston (1960-11-05). "Art: Eternally Beautiful: Four Oil Studies of Lady Hamilton by Romney on View". New York Times. New York, New York. p. X17.

Mountains, gorges, upland and lowland, are translated into curiously evocative flat or upright shapes, which, though no geographical phenomena are specifically duplicated, manage to give the lie or rise of the land.

- Robert McDonald (1961-04-30). "Puts Visible World Into Her Sculptures". New York Daily News. New York, New York. p. 148.

- Sanka Knox (1971-06-17). "Brandeis Merger Is Set for Riverside Museum". New York Times. New York, New York. p. 27.

- Christopher Gray (1995-01-29). "Streetscapes: The Master Apartments; A Restoration for the Home of a Russian Philosopher". New York Times. New York, New York. p. R7.

- Vivian Raynor (1981-10-18). "Stamford Museum & Nature Center Three Connecticut Abstractionists". New York Times. New York, New York. p. A16.

- Edward Alden Jewell (1944-04-12). "52d Show Opened by Women Artists". New York Times. New York, New York. p. 17.

- "19 Prizes Awarded to Women Artists". New York Times. New York, New York. 1945-04-21. p. 18.

- Aline B. Louchheim (1952-02-10). "2 Museums Champion Modern Art As Sculptors Assail Metropolitan; Museums Defend Modernism in Art". New York Times. New York, New York. p. 1.

New coals were heaped yesterday on the smoldering fires of dissension that have been burning for some time in the art world because of the disagreement between the modernist and classical points of view. The Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, both members of the modernist camp, issued statements defending the integrity of their institutions and the broad cross-sectional point of view adopted by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in its contemporary exhibition of sculpture.

- "4 Art Groups Join "Modernism" Fray". New York Times. New York, New York. 1952-04-26. p. 18.

- "American Sculpture 1951". College Art Journal. College Art Association. 11 (4): 280–289. 1952. doi:10.2307/773463. JSTOR 773463.

- "In New York Galleries; Constantin Brancusi's Sculpture". New York Times. New York, New York. 1926-11-21. p. X10.

- "Wife Is Forum Leader Steel's Best Listener; She Did Portrait of Editor in Modernist Style, Then Became His Bride". Des Moines Tribune. Des Moines, Iowa. 1936-03-03. p. 7.

'Modernism in sculpture,' she said, 'should be experienced in the same way as music. Because the piece of sculpture does not look to you as grandfather always looked with his pipe does not mean that such a work of sculpture has no meaning. A song, a work of music, creates a different impression on everyone who hears it. Modernism in sculpture is like music in form.'

- Ronald L. Sakaguchi; John M. Powers (16 July 2012). Craig's Restorative Dental Materials. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-323-08251-8.

- Laurie Wilson (16 December 2016). Louise Nevelson: Light and Shadow. Thames & Hudson. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-500-77374-1.

- "Catskills Colonies: Onteora Club's Artistic Beginnings". Brownstoner. Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- "An Artists' Retreat" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- "H.A. Caparn Dead; Landscape Architect". New York Times. New York, New York. 1945-09-25. p. 22.

- "Deaths: Caparn, Clara (Royall)". New York Times. New York, New York. 1970-07-20. p. 27.

- "Fine Work in New Studio". The Musical Leader. Musical Leader Publishing Co., Chicago. 36 (22): 520. 1918-11-28.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- "Recital to Assist "An Hour of Music": Karin Branzell Will be Heard". New York Times. New York, New York. 1944-03-05. p. 33.

- "Marriage Announcement". New York Times. New York, New York. 1906-10-19. p. 9.

- "George Claiborne Royall (1860–1943)". Find A Grave. Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- "Gen. Royall, Ex-Secretary of Army, Dies". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. 1971-05-27. p. 53.

- University of North Carolina (1793-1962); University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (1924). Alumni History of the University of North Carolina. Christian & King printing Company. p. 538.

- "Neighborhood Notes". Chapel Hill Weekly. Chapel Hill, North Carolina. 1946-03-29. p. 5.

- Allisa Frane (1915-08-08). "Westchester County Vows Not to Be Dull". The New York Tribune. New York, New York. p. 4.

There are in the county of Westchester during the summer months almost more actors, dramatists, musicians, authors and painters than in any other district of America. These would as gladly give of their gifts as the hundreds and hundreds would be to receive is the discovery of Mrs. Harold ap Rhys Caparn, the well known singer and teacher, whose professional name is Mrs. C. Howard Royall, founder of the Art Alliance of Westchester County.

- Arthur Hastings Grant; Harold Sinley Buttenheim (1923). The American City. Buttenheim Publishing Corporation. p. 607.

- "Social Notes". New York Times. New York, New York. 1926-03-23. p. 22.

- "Many to See the Premiere". New York Times. New York, New York. 1927-10-30. p. X13.

Two of the debutantes, the Misses Anne and Rhys Caparn, daughters of Mr. and Mrs. ap Rhys Caparn, who will be included in the list during the season, have an interesting lineage. They are directly descended from the Stuarts of the one-time reigning House of England and they have a long line of Colonial ancestry from those who made history in North Carolina and Virginia. Miss Anne Caparn was formally introduced to society last year in France, where she was at school. A luncheon will be given for her at the Colony Club on Nov. 12. Mrs. Caparn will give a series of luncheons at the Cosmopolitan Club for Miss Rhys yarn during December and January.

- The Saga Of American Society A Record Of Social Aspiration 1607-1937. Charles Scribner's Sons. 1937. p. 230.

- "Four Win Bryn Mawr Entrance Prizes". Bridgeport Telegram. Bridgeport, Connecticut. 1927-08-03. p. 5.

- "Miss Caparn's Wedding Was Not Elopement". The New York Post. New York, New York. 1935-11-05. p. 8.

- "Johannes Steel, 80, Commentator [Obituary]". New York Times. New York, New York. 1981-12-03. p. 33.

- John M. Spalek; Konrad Feilchenfeldt; Sandra H. Hawrylchak (15 August 2020). USA. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-908255-18-5.