Richard Watts

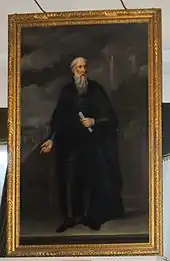

Richard Watts (1529–1579) was a successful businessman and MP for Rochester, South East England, in the 1570s. He supplied rations for the English Navy as deputy victualler and supervised the construction of Upnor Castle. After Queen Elizabeth I pronounced his house was "satis" (Latin for enough) after a visit in 1573, the house was thereafter known as Satis House.[1] Famed locally for his philanthropy, he died on 10 September 1579, leaving money in his will to establish the Richard Watts Charity and Six Poor Travellers House in Rochester High Street. He is buried, in accordance with his will, in Rochester Cathedral.

Richard Watts | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1529 |

| Died | September 10, 1579 |

| Resting place | Rochester Cathedral 51.388962°N 0.503293°E |

| Citizenship | English |

| Occupation | Businessman, MP |

| Years active | 1536–1571 |

| Known for | Philanthropy |

Notable work | Richard Watts Charity |

| Board member of | Rochester Bridge Trust |

Biography

The precise date and place of Richard's birth is uncertain. A Richard Watts born in West Peckham in 1529 is believed to be Richard Watts of Rochester.[2] However, there is evidence of an older Richard Watts living on Boley Hill, at a date during the supposed childhood of the Richard Watts born in West Peckham.[3] Little is known of the early life of Richard Watts. He may have spent his youth in Rochester gaining employment with Bishop (later Saint) John Fisher.[4][lower-alpha 1] Following the arrest and execution of Fisher, Watts returned to Rochester in a state of poverty.

By 1550, Richard Watts was established as a merchant. Payments were made to him for victualling the army and navy in 1550 and 1551.[1] In either 1552 (Lane & Singh) or 1554 (Hinkley) he was appointed deputy victualler of the navy. The earlier date fits in with the grant of a coat of arms in 1553. In 1559, he was reappointed to the post. Subsequently, Queen Elizabeth I appointed him as paymaster and surveyor of works when building of Upnor Castle started in 1560.[1][5][lower-alpha 2][6] A further royal appointment, that of surveyor of ordnance, followed in 1562. In 1560, as well as his appointment to the castle, he became paymaster to the Wardens of Rochester Bridge. In 1563, he was elected as MP for Rochester which seat he held until 1571.[7]

Richard died on 10 September 1579 at home. His will starts with "First I bequeath my Soule unto the Holy Trinity as is aforesaid[lower-alpha 3] and my Body to be buried in The Cathedrall Church of Rochester aforesaid neare unto the Steeple and Staires going up into the Quire on the South side of the same Staires". His will goes on to describe a procession from his house to the cathedral complete with curate and the "singing children" from the cathedral all "in their Surplices". After a service and sermon, he was to be buried. Various disbursements are made to those taking part, including to the sextons for digging the grave and ringing his knell "with all the bells". Even the congregation was remembered for unto every "poore Body" attending the burial he left "One penney in bread and One penny in money". He earmarked five pounds for this so was assuming an attendance of some 600 poor mourners.[lower-alpha 4]

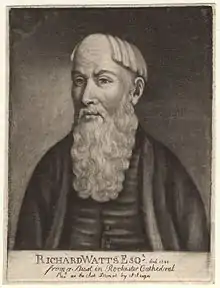

His grave, with coat of arms and simple inscription, is close to the south side of the pulpitum steps, just where he wanted it. In 1730, just over 150 years after his death, the city council resolved to erect a monument to his memory. A Mr. Charles Easton was tasked with the same for a sum of £50 (equivalent to £318 in 2019[lower-alpha 5]).[8] The memorial in the south transept of the cathedral incorporates the bust mentioned above. The bust appears to have been given by Josiah Brooke the current owner of Satis house, for below the bust and above the inscription[lower-alpha 6] a bold statement testifies: "Archetypum hunc dedit IOS. BROOKE de SATIS Arm".

The will

Watts' instructions for his funeral take up the first quarter of his will.[9] The next part of the will leaves money and income to his wife and details what should happen if she remarried, which she in due course did. A few other family bequests follow, then the main charitable section starts. The old almshouse beside the market cross was to be extended and refurbished with provision for casual travellers. There was provision for raw materials to be given to the poor to enable them to earn a living.[lower-alpha 7] Later the Mayor, principal citizens and commonalty of Rochester are enjoined to "preserve and maintain the stocke" so that the "yearely gaine and proffitts thereof riseing shall imploy to the uses and purposes aforesaid ... principally to the reliefe and comfort of the said poore Travellers". He laid upon his heirs the duty to supervise the Mayor and appointed the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Rochester as having the final say in any disposals.

The will was proved on 25 September 1579 "in common form" and before witnesses on 25 November the following year.[10] City accounts for 1579 show that this was not without cost: a gallon of wine to the Bishop's chancellor for the proving (2s), a trip to London (13s 4d), a copy of the will (5s) and others "aboute the probate" (20s 10d).[10] £2-1-2 in those days is equivalent to £635 in 2019[lower-alpha 5].

The will was not without its problems. Some of the properties disposed of were jointly owned with his wife, who therefore became the sole owner on his death. Some of the lands he had bequeathed had reverted (either on death or previously) to former owners, including a set of tenements which the Bishop took back.[11] Marian did remarry and according to the will should have lost the house. However she and her new husband, a lawyer named Thomas Pagitt, wished to keep the house.[1]

In 1593, a document was drawn up between the four parties interested in the will: Thomas & Marian, Mayor & citizens, Dean & Chapter, and the Bridge Wardens. The document was called the "Indenture Quadripartite".[12] In brief (the indenture is over 14 pages long when set in modern print) Marian was allowed to keep the house in return for giving up all other claims and returning the 100 marks left to her in the original will. The bulk of the document establishes the form and government of the charity which now bears Richard Watts' name.

Richard Watts Charities

Richard Watts' will when proved in 1579 provided for an almshouse in Rochester High Street. now known as the Six Poor Travellers House, to be expanded and maintained. The "Indenture Quadripartite" of 1593 established the form and government of Richard Watts Charity which over time built other almshouses and expanded to incorporate several local charities, such as St Catherine's Hospital founded under the charity of Symond Potyn in 1315. Richard Watts Charities, as of 2013, provides 66 self-contained flats in Rochester which includes almshouses in Maidstone Road built in 1857.[13]

1853 onwards

The Charitable Trusts Act of 1853 brought a large number of independent trusts and charities under the supervision of the newly created Charity Commissioners. Watts' Charity was no exception. A new scheme was devised for the running of the charity. The charity was run buy Municipal Trustees who appointed a Clerk and Receiver. They also appointed a Master and Matron to manage the poor travellers house. £4,000 was used to build a new set of almshouses for 20 people in Maidstone Road. £100 was set aside to provide an apprenticeship premium for children who had distinguished themselves at school. £2,000 was spent on the building of the Watts Public Baths with £200 per annum for maintenance. In 1935, they passed into the hands of the Corporation of Rochester though the annual grant towards costs continued for a further 20 years.

£4,000 was granted to the Trustees of St. Bartholomew's Hospital, Rochester to enable them to build a "Hospital and Dispensary for the relief of the Sick poor".[14] The charity was also to pay £1,000 (later raised to £1,500) per annum to the hospital and gained the right to nominate as patients up to 20 people at any one time.[14] These donations were maintained until 1948 until the hospital came under the control of the National Health Service.

In 1886, there was a further scheme extending the work of the charity. 11 outpensions of 7/- (35p) per week were established and two exhibitions of £100 made available annually, one each to Sir Joseph Williamson's Mathematical School and Rochester Grammar School for Girls. There were five exhibitions for pupil teachers, each of £6/5/0 annually for three years. The Watts Nursing Service was established with two full-time nurses (one midwife, one district) and six occasional nurses.[15]

The 1934 supplementary scheme increased certain payments and handed the baths over to the council.

Post war

The 1942 Beveridge Report led to the establishment of the modern British Welfare State. The previous, limited, National Insurance Act 1911 was extended to most workers by the National Insurance Act 1946. The National Health Service Act 1946 introduced universal health care and the National Assistance Act provided a safety net replacing the old Poor Laws. The upshot was that by 1950 much of the charity's former purpose had been taken over by the state.

A review of operations led to the scheme of 1954. Some money was available to help travellers in need of financial assistance and some for "amenities or samaritan funds" at hospitals within the city.[16] Some money was available for apprenticeships, for books, tools, fees and examinations. Power was obtained for discretionary grants to relieve hardship or distress, either directly or via other institutions.[16]

By 1976, sufficient funds were available to extend the almshouses. In 1977, yet another scheme came into operation. Several charities, some of which were already administered by the Trustees of Richard Watts Charity were amalgamated under the title: "Richard Watts and the City of Rochester Almshouse Charities":

- Richard Watts General

- Hayward's Almshouses

- The Chatham Intra Charity of Richard Watts

- St. Catherine's Hospital Charities

Watts' Nursing Service

The scheme of 1855 set up a nursing service to provide maternity care and to care for the afflicted poor of the parish. Any of the inmates of the Almshouses were able to call on their services in time of sickness. Care was free. A Head Nurse supervised the service, relying on nurses to provide the actual care. The Head Nurse periodically attended on all those in the care of nurses to check on the standard of work. She also had to visit all inmates of the almshouses once a week, ensure adequate fire precautions and prepare the boardroom for meetings.[17]

Things did not always go smoothly. Thomas Aveling complained in January 1871 about "the reported inefficiency of the Nurses ... more than twelve months since", which is interesting because as mayor 1869–70 he had a level of supervision of the charity.[18][19] On 2 June 1871 he was appointed to be a trustee at around the same time he left the council.

During the 1930s home-helps were employed by the charity to assist new mothers for up to 21 days after the birth. They were expected to attend from 8 am to 8 pm and to cook, supervise older children (getting them to school and afterwards to bed) and wash the children's clothes. Washing the patient and making the bed were, however, the prerogative of the nurse.[20] Although the scheme seemed to work well, it was too expensive for the charity and the home-helps were discontinued after 1938.

The scheme was not without problems. In 1941 the Royal College of Nursing exprtessed concern to the trustees for "advertising for a SRN [State Registered Nurse] for district work at a salary of £130 p.a."[21] Eventually an increase of £50 p.a. was agreed for each nurse. In 1945 the Nurses' Salaries Commission reported and the Ministry of Health established norms for the profession. Thereafter the rates agreed by the Whitley Council were paid.

The coming of the National Health Service (NHS) in 1946 brought a dramatic change to the charity. The county council had the task of organising a free home nursing service for all persons who needed it. Local organisations could participate, they would need to fund 25% of the cost, the county providing the remaining 75%.[22] The charity's nursing service was incorporated on this basis into the NHS with the county funding £2,000 and the charity £1,500. The Charity Commissioners were not happy with a charity becoming permanently involved in the NHS and only permitted the arrangement to run until December 1950.[23] The nursing service continued to provide a reduced independent service until all patients were transferred to the NHS on 31 March 1958. The Nursing Branch of the charity then ceased to exist.[24]

Watts Public Baths

The 1855 scheme empowered the trustees to erect public baths and washhouses. There was a site by the river which had been occupied by the baths of the Castle Club. The trustees duly obtained it and built new baths, opening in 1880. Both private baths and swimming baths were provided. The swimming baths were used by schools. Between 1882 and 1925, some three and a half thousand children had learnt to swim there. The baths were never run profitably, a yearly grant of £200 from the charity being required. Finally in 1935, the baths were handed over to Rochester Corporation, though the annual grant remained for a further 15 years.[25]

Satis House

Queen Elizabeth I was the guest of Richard Watts during her royal progress of 1573.[1] When he asked her if his house was to her liking, she replied 'Satis' (Latin for 'enough'). The house was thereafter known as 'Satis House'.[1]

Archbishop Longley was born in Satis house in 1794.[26]

The house has been rebuilt and is now the administration building for The King's School, Rochester. A bust of Watts has been set on top of the building's portico. Although Charles Dickens in his novel Great Expectations used the name Satis House for Miss Havisham's house, his biographer, John Forster, felt that some aspects of the fictitious Satis House were modelled on nearby Restoration House.[27]

References

- Footnotes

- Hinkley notes that Bell does not give his sources.

- "August 15 [1562]: 12. Account of the monthly charges of the new block-house at Upnor; conveyance of materials, &c.; by Ric. Watts, paymaster."

- The preamble to the will starts with a creed and prayer.

- There were 240 pennies to the pound.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Sacred to the Memory of RICHARD WATTS Eʃq; a principal Benefactor to this City, who departed this life Sept.10.1579.at his Mansion house on Bully-hill, call'd SATIS,(so named by Q.ELIZABETH of glorious memory,) and lies interr'd near this place, as by his Will doth plainly appear.By which Will,dated Aug.22.and proved Sep 25.1579 he founded an Almshouse for the relief of poor people,and for the reception of six poor Travelers every night, and for imploying the poor of this City. The Mayor & Citizens of this City, in teʃtimony of their Gratitude & his Merit, have erected this Monument.A.D.1736. RICHARD WATTS Eʃq: then Mayor.

- "Hempe Flaxe Yarne wool and other necessarie Stuffe to sett the poore of the said Citty [Rochester] a worke"

- Citations

- Seccombe 1899.

- Hinkley 1979, p. 7.

- Lane & Singh 2014a.

- Bell 1938: quoted by Hinkley 1979, p. 7

- Colvin 1982, pp. 478–479.

- Lemon 1856, p. 204.

- Hinkley 1979, p. 8.

- Hinkley 1979, p. 16.

- Hinkley 1979, Appendix 1, for the full text of the will.

- Hinkley 1979, p. 12.

- Hinkley 1979, p. 13.

- Hinkley 1979, Appendix 2, for the full text of the indenture.

- Lane & Singh 2014b.

- Hinkley 1979, p. 20.

- Hinkley 1979, p. 22.

- Hinkley 1979, p. 25.

- Hinkley 1979, pp. 63–65.

- Hinkley 1979, p. 64.

- Brown 2004.

- Hinkley 1979, p. 65.

- Hinkley 1979, p. 68.

- Hinkley 1979, p. 69.

- Hinkley 1979, p. 70.

- Hinkley 1979, p. 71.

- Hinkley 1979, chapter 8.

- Hughes 1892, p. 157.

- Forster 1872.

- Bibliography

- Bell, R.J. (December 1938), The Dental Magazine and Oral Topics Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Brown, Jonathan (2004), "Aveling, Thomas (1824–1882)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 26 July 2012

- Colvin, Howard, ed. (1982), The History of the King's Works, vol 4 part 2, HMSO

- Forster, John (1872), "The Life of Charles Dickens", www.lang.nagoya-u.ac.jp, Cecil Palmer, retrieved 9 November 2013

- Hinkley, E.J.F. (1979), A History of the Richard Watts Charity, Rochester: Richard Watts and the City of Rochester Almshouse Charities, ISBN 0-905418-76-X Note: limited edition of 200 copies, a copy is available from Medway libraries.

- Hughes, William R. (1892), A Week's Tramp in Dickens-Land (Project Gutenberg eBook), Chapman & Hall, pp. 142–160, retrieved 18 January 2015

- Lane, Kieran; Singh, Karun (19 September 2014a), "Richard Watts", Richard Watts Charities, retrieved 18 January 2015

- Lane, Kieran; Singh, Karun (19 September 2014b), "Watts Almshouses, Maidstone Road", Richard Watts Charities, retrieved 18 January 2015

- Lemon, Robert, ed. (1856), Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the Reigns of Edward VI., Mary, Elizabeth, 1547-1580, preserved in the state paper department of Her Majesty's Public Record Office, London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans & Roberts, retrieved 18 January 2015

- Lucy, Henry William (1892), "Chapter 9. Christmas Eve at Watts's", Faces and Places (Project Gutenberg eBook), Henry and Co, pp. 86–99, retrieved 28 June 2012

- Phippen, James (1862), Descriptive Sketches of Rochester, Chatham and their Vicinities Quoted by Hinkley.

- Seccombe, Thomas (1899). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 60. London: Smith, Elder & Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)