Ritonavir

Ritonavir (RTV), sold under the brand name Norvir, is an antiretroviral medication used along with other medications to treat HIV/AIDS.[2] This combination treatment is known as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).[2] Often a low dose is used with other protease inhibitors.[2] It may also be used in combination with other medications for hepatitis C.[3] It is taken by mouth.[2] The capsules of the medication do not work the same as the tablets.[2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Norvir |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a696029 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 98-99% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 3-5 hours |

| Excretion | mostly fecal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.125.710 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C37H48N6O5S2 |

| Molar mass | 720.95 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhea, and numbness of the hands and feet.[2] Serious side effects include liver problems, pancreatitis, allergic reactions, and arrythmias.[2] Serious interactions may occur with a number of other medications including amiodarone and simvastatin.[2] At low doses it is considered to be acceptable for use during pregnancy.[4] Ritonavir is of the protease inhibitor class.[2] Typically, however, it is used to inhibit the enzyme that metabolizes other protease inhibitors.[5] This inhibition allows lower doses of these latter medication to be used.[5]

Ritonavir was patented in 1989 and came into medical use in 1996.[6][7] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[8]

Medical uses

Ritonavir is indicated in combination with other antiretroviral agents for the treatment of HIV-1-infected patients (adults and children of two years of age and older).[1][2]

Side effects

When administered at the initially tested higher doses effective for anti-HIV therapy, the side effects of ritonavir are those shown below.[9]

- asthenia, malaise

- diarrhea

- nausea and vomiting

- abdominal pain

- dizziness

- insomnia

- sweating

- taste abnormality

- metabolic effects, including

- hypercholesterolemia

- hypertriglyceridemia

- elevated transaminases

- elevated creatine kinase

One of ritonavir's side effects is hyperglycemia, through inhibition of the GLUT4 insulin-regulated transporter, thus keeping glucose from entering fat and muscle cells. This can lead to insulin resistance and cause problems for people with type 2 diabetes.

Drug interactions

Ritonavir induces CYP 1A2 and inhibits the major P450 isoforms 3A4 and 2D6. Concomitant therapy of ritonavir with a variety of medications may result in serious and sometimes fatal drug interactions.[10] The list of clinically significant interactions of ritonavir includes the following drugs:

- amiodarone—decreased metabolism, possible toxicity;

- bosentan—decreased metabolism via CYP3A4;

- midazolam and triazolam—contraindicated;

- carbamazepine—decreased metabolism, possible toxicity;

- cisapride—decreased metabolism, possible prolongation of Q-T interval and life-threatening arrythmias;

- disulfiram (with ritonavir oral preparation)—decreased metabolism of ritonavir;

- eplerenone;

- etravirine;

- flecainide—decreased metabolism, possible toxicity;

- MDMA—decreased metabolism, can sometimes result in toxic outcomes such as serotonin syndrome, which can be life-threatening;[11][12]

- mescaline;

- meperidine (pethidine)—build-up of toxic concentrations of norpethidine possible;

- nilotinib;

- nisoldipine;

- oxycodone—greatly increased concentrations of oxycodone;[13]

- phenytoin—induction of phenytoin metabolism by CYP2C9;

- pimozide;

- quinidine;

- ranolazine;

- salmeterol;

- saquinavir—inhibition of its metabolism, but decrease bioavailability due to in vivo supersaturation;[14]

- St John's wort;

- statins—decreased metabolism, without dosage modification increased risk of rhabdomyolysis;

- thioridazine;

- topotecan;

- voriconazole—increased metabolism.

Mechanism of action

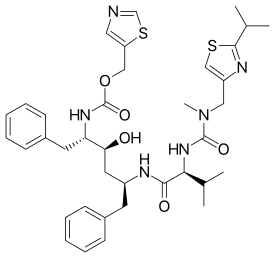

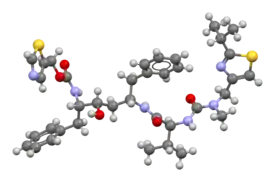

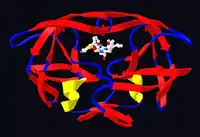

Ritonavir was originally developed as an inhibitor of HIV protease, one of a family of pseudo-C2-symmetric small molecule inhibitors.

Ritonavir is now rarely used for its own antiviral activity but remains widely used as a booster of other protease inhibitors. More specifically, ritonavir is used to inhibit a particular enzyme, in intestines, liver, and elsewhere, that normally metabolizes protease inhibitors, cytochrome P450-3A4 (CYP3A4).[15] The drug binds to and inhibits CYP3A4, so a low dose can be used to enhance other protease inhibitors. This discovery drastically reduced the adverse effects and improved the efficacy of protease inhibitors and HAART. However, because of the general role of CYP3A4 in xenobiotic metabolism, dosing with ritonavir also affects the efficacy of numerous other medications, adding to the challenge of prescribing drugs concurrently.[16]

Pharmocodymanics and pharmacokinetics

The capsules of the medication do not have the same bioavailability as the tablets.[2]

History

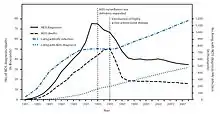

Ritonavir is manufactured as Norvir by AbbVie, Inc.. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved ritonavir on March 1, 1996,[18] making it the seventh U.S.-approved antiretroviral drug and the second U.S.-approved protease inhibitor (after saquinavir four months earlier). As a result of the introduction of new "highly active antiretroviral thearap[ies]"—of which the protease inhibitors ritonavir and saquinavir were critical—the annual U.S. HIV-associated death rate fell from over 50,000 to about 18,000 over a period of two years.[19][20]

In 2003, Abbott (now AbbVie, Inc.) raised the price of a Norvir course from US$1.71 per day to US$8.57 per day, leading to claims of price gouging by patients' groups and some members of Congress. Consumer group Essential Inventions petitioned the NIH to override the Norvir patent, but the NIH announced on August 4, 2004, that it lacked the legal right to allow generic production of Norvir.[21]

In 2014, the FDA approved a combination of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir for the treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 4,[3] where the presence of ritonavir again capitalizes on its inhibitory interaction with the human drug metabolic enzyme CYP3A4.

Polymorphism and temporary market withdrawal

Ritonavir was originally dispensed as an ordinary capsule that did not require refrigeration. This contained a crystal form of ritonavir that is now called form I.[22] However, like many drugs, crystalline ritonavir can exhibit polymorphism, i.e., the same molecule can crystallize into more than one crystal type, or polymorph, each of which contains the same repeating molecule but in different crystal packings/arrangements. The solubility and hence the bioavailability can vary in the different arrangements, and this was observed for forms I and II of ritonavir.[23]

During development—ritonavir was introduced in 1996—only the crystal form now called form I was found; however, in 1998, a lower free energy,[24] more stable polymorph, form II, was discovered. This more stable crystal form was less soluble, which resulted in significantly lower bioavailability. The compromised oral bioavailability of the drug led to temporary removal of the oral capsule formulation from the market.[23] As a consequence of the fact that even a trace amount of form II can result in the conversion of the more bioavailable form I into form II, the presence of form II threatened the ruin of existing supplies of the oral capsule formulation of ritonavir; and indeed, form II was found in production lines, effectively halting ritonavir production.[22] Abbott (now AbbVie) withdrew the capsules from the market, and prescribing physicians were encouraged to switch to a Norvir suspension.

The company's research and development teams ultimately solved the problem by replacing the capsule formulation with a refrigerated gelcap. In 2000, Abbott (now AbbVie) received FDA-approval for a tablet formulation of lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra) which contained a preparation of ritonavir that did not require refrigeration.[25]

Research

In 2020, the fixed-dose combination of lopinavir/ritonavir was found not to work in severe COVID-19.[26] In the trial the medication was started around thirteen days after the start of symptoms.[26] Virtual screening of the 1930 FDA-approved drugs followed by molecular dynamics analysis predicted ritonavir blocks the binding of the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein to the human angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (hACE2) receptor, which is critical for the virus entry into human cells.[27]

References

- "Norvir EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 20 August 2020. Text was copied from this source which is © European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- "Ritonavir". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-10-17. Retrieved Oct 23, 2015.

- "FDA approves Viekira Pak to treat hepatitis C". Food and Drug Administration. December 19, 2014. Archived from the original on October 31, 2015.

- "Ritonavir Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". drugs.com. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- British National Formulary 69 (69 ed.). Pharmaceutical Pr. March 31, 2015. p. 426. ISBN 9780857111562.

- Hacker, Miles (2009). Pharmacology principles and practice. Amsterdam: Academic Press/Elsevier. p. 550. ISBN 9780080919225.

- Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 509. ISBN 9783527607495.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "Norvir side effects (Ritonavir) and drug interactions - prescription drugs and medications at RxList". June 27, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-06-27.

- "Ritonavir: Drug Information Provided by Lexi-Comp: Merck Manual Professional". April 30, 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-04-30.

- Henry, J. A.; Hill, I. R. (1998). "Fatal interaction between ritonavir and MDMA". Lancet. 352 (9142): 1751–1752. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(05)79824-x. PMID 9848354. S2CID 45334940.

- Papaseit, E.; Vázquez, A.; Pérez-Mañá, C.; Pujadas, M.; De La Torre, R.; Farré, M.; Nolla, J. (2012). "Surviving life-threatening MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, ecstasy) toxicity caused by ritonavir (RTV)". Intensive Care Medicine. 38 (7): 1239–1240. doi:10.1007/s00134-012-2537-9. PMID 22460853. S2CID 19375709.

- Nieminen, Tuija H.; Hagelberg, Nora M.; Saari, Teijo I.; Neuvonen, Mikko; Neuvonen, Pertti J.; Laine, Kari; Olkkola, Klaus T. (2010). "Oxycodone concentrations are greatly increased by the concomitant use of ritonavir or lopinavir/ritonavir". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 66 (10): 977–985. doi:10.1007/s00228-010-0879-1. ISSN 0031-6970. PMID 20697700. S2CID 25770818.

- Hsieh, Yi-Ling; Ilevbare, Grace A.; Van Eerdenbrugh, Bernard; Box, Karl J.; Sanchez-Felix, Manuel Vincente; Taylor, Lynne S. (2012-05-12). "pH-Induced Precipitation Behavior of Weakly Basic Compounds: Determination of Extent and Duration of Supersaturation Using Potentiometric Titration and Correlation to Solid State Properties". Pharmaceutical Research. 29 (10): 2738–2753. doi:10.1007/s11095-012-0759-8. ISSN 0724-8741. PMID 22580905. S2CID 15502736.

- Zeldin RK, Petruschke RA (2004). "Pharmacological and therapeutic properties of ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor therapy in HIV-infected patients". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 53 (1): 4–9. doi:10.1093/jac/dkh029. PMID 14657084. Archived from the original on 2007-08-21.

- "Drug Development and Drug Interactions: Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). December 3, 2019.

- (PDF) https://web.archive.org/web/20150924044850/http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/wk/mm6021.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2020-02-17. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Ritonavir FDA approval package" (PDF). 1 March 1996.

- "HIV Surveillance—United States, 1981-2008". Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- The CDC, in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, ascribes this to "highly active antiretroviral therapy", without mention of either of these drugs, see the preceding citation. A further citation is needed to make this accurate connection between this drop and the introduction of the protease inhibitors.

- Ceci Connolly (2004-08-05). "NIH Declines to Enter AIDS Drug Price Battle". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2006-01-16.

- Bauer J; et al. (2001). "Ritonavir: An Extraordinary Example of Conformational Polymorphism". Pharmaceutical Research. 18 (6): 859–866. doi:10.1023/A:1011052932607. PMID 11474792. S2CID 20923508.

- S. L. Morissette; S. Soukasene; D. Levinson; M. J. Cima; O. Almarsson (2003). "Elucidation of crystal form diversity of the HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir by high-throughput crystallization". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100 (5): 2180–84. doi:10.1073/pnas.0437744100. PMC 151315. PMID 12604798.

- Lüttge, Andreas (February 1, 2006). "Crystal dissolution kinetics and Gibbs free energy". Journal of Electron Spectroscopy and Related Phenomena. 150 (2): 248–259. doi:10.1016/j.elspec.2005.06.007.

- "Kaletra FAQ". AbbVie's Kaletra product information. AbbVie. 2011. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- Cao, Bin; Wang, Yeming; Wen, Danning; Liu, Wen; Wang, Jingli; Fan, Guohui; et al. (18 March 2020). "A Trial of Lopinavir–Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe Covid-19". New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (19): 1787–1799. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. PMC 7121492. PMID 32187464.

- Bagheri, Milad; Niavarani, Ahmadreza (2020-10-08). "Molecular dynamics analysis predicts ritonavir and naloxegol strongly block the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-hACE2 binding". Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics. 0: 1–10. doi:10.1080/07391102.2020.1830854. ISSN 0739-1102. PMID 33030105. S2CID 222217607.

Further reading

- Chemburkar, Sanjay R.; Bauer, John; Deming, Kris; Spiwek, Harry; Patel, Ketan; Morris, John; Henry, Rodger; Spanton, Stephen; et al. (2000). "Dealing with the Impact of Ritonavir Polymorphs on the Late Stages of Bulk Drug Process Development". Organic Process Research & Development. 4 (5): 413–417. doi:10.1021/op000023y.