Robert Dighton

Robert Dighton was born c.1752 in London and died there in 1814. An English portrait painter, printmaker and caricaturist, he was the founder of a dynasty of artists who followed in his footsteps.

Life and work

Robert Dighton was the son of the London printseller John Dighton [1].. In the 1770s he began acting and singing in plays at the Haymarket Theatre, Covent Garden and Sadler’s Wells while at the same time training and exhibiting at the Royal Academy - he entered the Royal Academy Schools in 1722.[2] He also exhibited at the Free Society of Artists between 1769–73. The first prints he designed were of actors for John Bell's edition of Shakespeare (1775–76).

As an artist, he was first offered consistent employment by the publisher Carington Bowles (fl.1752–93). This was the heyday of the so-called 'droll' mezzotint and Robert's output of designs, executed in watercolour and then engraved, was an integral part of his stock. Carington Bowles was among of the most active mapsellers of his day in London, which will explain Dighton’s caricature maps in his “Geography Bewitched” series, including Ireland, England and Wales[3] and Scotland.[4]

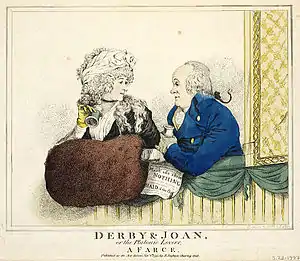

Much of Dighton's early work was issued anonymously, but by the early 1790s it became increasingly well known and he began etching and publishing under his own name. In awkward poses and with ruddy faces, Dighton's satirical caricatures included lawyers, military officers, actors and actresses who were seen about town, as well as down-at-heel types. In 1795 he brought out a Book of Heads and thenceforth devoted himself chiefly to caricature. His work is noted as being less savage than that of his contemporaries, James Gilray and George Cruickshank.

By the start of the century, his success allowed him to open a shop in Charing Cross, where he sold his own prints and those of others until it emerged in 1806 that part of his stock was stolen from the British Museum. An art dealer by the name of Samuel Woodburn had purchased a print, an impression of Rembrandt's Coach Landscape, from Dighton and, supposing it might be a copy, took the print to the British Museum to compare it with the impression there.[5] When it was discovered that their impression was missing, Dighton confessed that he had befriended a museum official by drawing portraits of him and his daughter during his visits and used this relationship to remove prints from the museum hidden in his portfolio.[6]

Because of his co-operation, Dighton escaped prosecution but was forced to lie low in Oxford until the scandal died down. While there he did an amusing series of portraits of academic types and country gentlemen, as well as in Bath and Cambridge.[7] Returning to London in 1810, he reopened his studio, where he worked with his sons until his death in 1814

The second and third generations

- Robert junior 1786-1865 etched military portraits between 1800–09 and then made a career in the military.[8]

- Denis 1792-1827 began in the military and then trained as an artist, specialising in military subjects.[9]

- Richard 1796?-1880. His father's apprentice, he continued his business from 1815 before moving to Cheltenham and Worcester.[10]

- Richard Dighton junior (1824–1891), Richard's elder son, later established himself as a photographer and had a studio in Cheltenham.

- Joshua Dighton (1831–1908), Richard's second son, was born in Worcester and well known for his portraits of jockeys. He was active in the London area as a portraitist and photographer.[11]

Notes

- "Robert Dighton (British Museum Biographical details)".

- Bryant, Mark; Henneage, Simon (1994). Dictionary of British Cartoonists and Caricaturists, 1730-1988. London, England: Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd. p. 61. ISBN 978-0859679763.

- Map Forum

- Wikimedia

- Van Camp, An (2013). Robert Dighton and his spurious collectors' marks on Rembrandt prints in the British Museum, London', in The Burlington Magazine 155. London, England: The Burlington Magazine. pp. 88–94.

- Griffiths, Anthony (1996). Landmarks in Print Collecting. London, England: British Museum. pp. 10, 49–50, 60, 276–831.

- Examples of his work from this period can be viewed here

- National Portrait Gallery

- National Portrait Gallery

- National Portrait Gallery

- National Portrait Gallery

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bryan, Michael (1886). "Dighton, Robert". In Graves, Robert Edmund (ed.). Bryan's Dictionary of Painters and Engravers (A–K). I (3rd ed.). London: George Bell & Sons.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bryan, Michael (1886). "Dighton, Robert". In Graves, Robert Edmund (ed.). Bryan's Dictionary of Painters and Engravers (A–K). I (3rd ed.). London: George Bell & Sons. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1888). "Dighton, Robert". Dictionary of National Biography. 15. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 74–5.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1888). "Dighton, Robert". Dictionary of National Biography. 15. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 74–5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert Dighton. |

- 270 works at the National Portrait Gallery

- Works in galleries and elsewhere online at Art Cyclopaedia