Rollin White

Rollin White (June 6, 1817 – March 22, 1892) was an American gunsmith who invented a single shot bored-through revolver cylinder that allowed paper cartridges to be loaded from the rear of a revolver's cylinder. Because the open breeches were unprotected from lateral fire, all charges would instantly explode in a chain fire. Only one gun would be built to White's specifications, and that for use in a trial to show the impracticality of the gun. The gun could not fire metallic cartridges.

Rollin White | |

|---|---|

| Born | Rollin White June 6, 1817 Williamstown, Vermont, United States |

| Died | March 22, 1892 (aged 74) |

| Occupation | Inventor, gunsmith |

Early life

White was born in Williamstown, Vermont in 1818. He learned gunsmithing from his older brother, J. D. White in 1837 and would later claim that the idea for a "rear-loading" Pepper-box revolver came to him while working in his brother's shop in 1839. In 1849 he went to work for his brothers who had a contract at Colt's Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company for turning and finishing revolver barrels. During this time he appropriated two "junk" or scrapped revolver cylinders from Colt and placed them in his barrel lathe, cutting the front off one and the rear off the other. He assembled these parts into a single bored-through cylinder that would fit in a Colt revolver.[1]

Rollin White patent

Up until that time, revolvers were black-powder percussion arms. The shooter had to pour powder into each of the six cylinder mouths, push a bullet into the chamber, and affix a percussion cap on the rear of the cylinder, making the reloading process cumbersome.

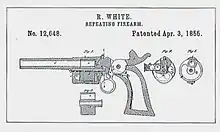

While the cartridge revolver was known in Europe, Rollin White's famous patent combined a cylinder and a box magazine. It was a completely unworkable design which never went into production (only one sample was built which malfunctioned dramatically),[2] yet it was the first US patent to include a cylinder bored through so that a revolver could be loaded from the breech. White's original solution for the misfires that plagued early revolvers was to plug the rear of the chambers with pieces of leather, but to admit cap fire the plugs were pierced, making them useless. The patent drawings imply that a percussion cap would have had to be applied to the single nipple for each shot, so it would have been far slower than the existing cap-&-ball revolvers.[3]

White left Colt's in December 1854. Within three months he had five patents, including Patent 12648 which was for an "Improvement in Repeating Fire-arms".[4][5] The next year, White signed an agreement granting Smith & Wesson the exclusive use of his patent for boring through the chambers, but not the rest of the patent. White retained a royalty rate of 25 cents for every revolver.[6]

Smith & Wesson parlayed the bored-through claim into a monopoly on the breech-loading revolver. After the Smith & Wesson Model 1 revolver came on the market, White began production of a revolver of his own in 1861 in a factory in Lowell, Massachusetts called "Rollin White Arms Company". Approximately 4300 revolvers were made under Rollin White Arms, most of which were sold to Smith & Wesson to keep up with demand. White liquidated the company in 1864 and the assets were bought by Lowell Arms Company, which began manufacturing revolvers directly infringing on White's patent. White sued them, but not until after they had made 7500 revolvers.[7]

White and S&W brought infringement cases against Manhattan Firearms Company, Allen & Wheelock, Merwin & Bray, National Arms Company and others. The courts mostly sided with White, but allowed these manufacturers to continue production runs, with a royalty paid to White. In some cases, Smith & Wesson bought the guns back to remark and sell; such guns are marked "APRIL 3 1855" as a patent date.[8] Eventually, the matter was litigated as White, et al. v. Allen in the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Massachusetts; Allen acknowledged his gun infringed on the patent, but challenged the patent itself. The court sided with White, though not without controversy. In addition to White's design not actually being functional, prior art existed of revolvers with bored-through cylinders predating his patent. Casimir Lefaucheux and his son Eugène had invented a bored-through cylinder revolver for pinfire cartridges and patented it on April 15, 1854 (almost exactly one year before White's patent was granted), which should have invalidated the applicability of White's patent to the concept of a bored-through cylinder. The vote in the Supreme Court to affirm White's patent was tied with four for it and four against.[9][10]

In 1863, White had another of his patents, US Patent 12649, which was for a front-loaded gun, reissued with a breech-loading feature. This gave White two patents of the same date for the same invention. White made life for Smith & Wesson miserable with constant threats of suits, for now with each gun they made under Patent 12648, they infringed Patent 12649. In 1867 White and Smith & Wesson offered to sell the patent to Colt's for $1 million. Colt's, anxious to begin the manufacture of breech-loading guns, dealt with White for some time. That stopped when they learned of the second patent which Colt's declined.

Rollin White Relief Act

After being denied a patent extension, White lobbied Congress for relief in 1870, urging Congress to consider that he had not been fairly compensated for his invention; he made only $71,000, while Smith & Wesson earned over $1 million for his idea. Furthermore, White pointed out that the bulk of his earnings was spent on litigation as others infringed on his idea.[11] This was untrue, as White avoided his obligation to pay for legal costs by assigning the royalty to his wife. He paid $17,000 in legal costs, but after that Smith & Wesson never saw another penny from White.

Congress passed a bill granting White a rehearing, styled: An act for the relief of Rollin White (S.273), but the bill was vetoed by President Ulysses S. Grant, citing objections from Chief of Ordnance Alexander Brydie Dyer.[12] Dyer claimed that White's patent litigation during the American Civil War served as "an inconvenience and embarrassment" to Union forces for the "inability of manufacturers to use this patent". Dyer went on to write that "its further extension will operate prejudicially to its interests by compelling it to pay to parties already well paid a large royalty for altering its revolvers to use metallic cartridges."[12] No further votes were held and the bill died. Rollin White continued his efforts with Congress, and by 1877 he finally gave up any possibility of extension.

Other works

White invented the knife-edge breech block and self-cocking device for the "box-lock" Model 1851 Sharps rifle. These rifles were built by White, Christian Sharps, and Richard Lawrence at Robbins & Laurence in Windsor, Vermont. White later designed a self-cocking mechanism for the 1855 pattern Sharps and built 50 of these rifles for a potential US Navy contract, but the Navy only purchased 12 of them.[13]

Rollin White died in Lowell, Massachusetts on March 22, 1892.[14]

References

- Allen, Ethan (1863). "Deposition of Rollin White". Circuit court of the United States,Massachusetts district: In equity. For complainants: E. W. Stoughton, C. M. Keller, E. F. Hodges. For respondents: B. R. Curtis, Caustin Browne. pp. 187–193.

- Winant, Lewis (1959). Early Percussion Firearms. Great Britain: Herbert Jenkins Ltd. pp. 145–146. ISBN 0-600-33015-X.

- Boorman, Dean K. (2004). Guns of the Old West: An Illustrated History. Lyons Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-59228-638-6.

- US patent 12648, Rollin White, "Improvement in repeating fire-arms", published 1855-04-03

- Ware, Donald L. (2007). Remington army and navy revolvers, 1861–1888. UNM Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-8263-4280-5.

- Jinks, Roy G.; Sandra C. Krein (2006). Smith & Wesson Images of America. Arcadia Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7385-4510-3.

- Flayderman, Norm (2001). Flayderman's Guide to Antique American Firearms ... and their values. Iola, WI: Krause Publications. p. 213. ISBN 0-87349-313-3.

- Walter (2006)p.108

- "WHITE ET AL. V. ALLEN" (PDF). 1863.

- https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=9jRHAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA81&lpg=PA81&dq=Rollin+White+Patent&source=bl&ots=2-0cmT1QK4&sig=ACfU3U04n6csKIYOGVKRNa6Cf3ewjeFpNA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi-pbyHu6zoAhUvQEEAHbGgABI4FBDoATAAegQICRAB#v=onepage&q=Rollin%20White%20Patent&f=false

- Satterlee (1940) p. 151

- Grant, US (1897). James Daniel Richardson (ed.). A compilation of the messages and papers of the presidents, prepared under the Joint Committee on Printing of the House and Senate, pursuant to an act of the Fifty-second Congress of the United States (with additions and encyclopedic index by private enterprise). A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, Prepared Under the Joint Committee on Printing of the House and Senate, Pursuant to an Act of the Fifty-second Congress of the United States. 9. Bureau of National Literature. pp. 4034–4035.

- Walter, John (2007). Rifles of the World (3 ed.). Krause Publications. pp. 437–438. ISBN 978-0-89689-241-5.

- Satterlee, Leroy De Forest; Arcadi Gluckman (1940). American gun makers. O. Ulbrich. p. 95.

External links

- U.S. Patent 00,012,648, April 3, 1855 patent covering the bored-through cylinder in a revolver

- U.S. Patent 00,093,653, August 10, 1869 patent covering an automatic extractor for break-open revolvers