Saltmarsh sparrow

The saltmarsh sparrow (Ammospiza caudacuta) is a small New World sparrow found in salt marshes along the Atlantic coast of the United States. At one time, this bird and the Nelson's sparrow were thought to be a single species, the sharp-tailed sparrow. Because of this, the species was briefly known as the "saltmarsh sharp-tailed sparrow."

| Saltmarsh sparrow | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Passerellidae |

| Genus: | Ammospiza |

| Species: | A. caudacuta |

| Binomial name | |

| Ammospiza caudacuta (Gmelin, 1788) | |

| |

This bird's numbers are declining due to habitat loss largely attributed to human activity.

Description

The saltmarsh sparrow measures 11–14 cm (4.3–5.5 in) in length, has a wingspan of 17.8–21 cm (7.0–8.3 in), and weighs 14–23.1 g (0.49–0.81 oz).[2][3] Adults have brownish upperparts with a gray nape, white throat and belly, and pale orange breast and sides with brown streaking. The face is orange with gray cheeks, a gray median crown stripe, brown lateral crown stripes, and a brown eyeline. The tail feathers are short and sharply pointed.[4]

Distinguishing this species from closely related sparrows such as the Nelson's sparrow can be difficult. The inland subspecies of the Nelson's sparrow can be differentiated by its fainter streaking and brighter orange breast and sides, while the coastal subspecies of the Nelson's sparrow can be differentiated by its paler, less-contrasting plumage. The saltmarsh sparrow also has a slightly longer beak than the Nelson's sparrow.[4]

Taxonomy

The species name caudacuta is Latin for "sharp-tailed." [5] Its closest relatives are the Nelson's sparrow (Ammospiza nelsoni) and the Seaside sparrow (Ammospiza maritima).[6][7]

The saltmarsh sparrow and the Nelson's sparrow were once thought to be a single species, called the sharp-tailed sparrow. Mitochondrial DNA evidence suggests that the two species diverged about 600,000 years ago.[8] A Pleistocene glaciation is thought to have separated the ancestral sharp-tailed sparrow into inland and coastal populations. The inland Nelson's sparrow became a specialist of non-tidal freshwater wetlands while the coastal saltmarsh sparrow became a specialist of tidal salt marshes.[9] Recently, the Nelson's sparrow has expanded its range to include coastal salt marshes, and interbreeding occurs where the two species overlap.[10][11]

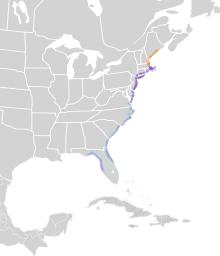

The saltmarsh sparrow is divided into two subspecies. The northern subspecies, A. caudacutus caudacutus, breeds from Maine to New Jersey, while the southern subspecies, A. caudacutus diversus, breeds in Maryland and Virginia. A. c. diversus has more contrasting striping on its back and a darker crown than A. c. caudacutus.[12]

Habitat and Distribution

The saltmarsh sparrow is only found in tidal salt marshes along the Atlantic coast of the United States. It breeds along the northern coast, from Maine to the Chesapeake Bay, and winters along the southern coast, from North Carolina to Florida.[13] The saltmarsh sparrow prefers high marsh habitat, dominated by saltmeadow cordgrass (Spartina patens) and saltmarsh rush (Juncus gerardii), which does not flood as frequently as low marsh.[14]

Behavior

Vocalizations

Only males sing.[13] The song is a complex series of raspy, barely audible buzzes, trills, and gurgles. It is distinguishable from that of the Nelson's sparrow, which is a louder, hissing buzz followed by a buzzy chip. The high-pitched contact calls of both species are indistinguishable.[4]

Diet

The saltmarsh sparrow forages on the ground along tidal channels or in marsh vegetation, sometimes probing in the mud at low tide. Over 80% of its diet consists of flies, amphipods, grasshoppers, and moths, especially larval, pupal, and adult soldier flies.[15] During the winter, it also eats seeds.[13] The saltmarsh sparrow is an opportunistic feeder and food is rarely limiting.[15]

Reproduction

.jpg.webp)

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Saltmarsh sparrows are non-territorial and have large overlapping home ranges. Male home ranges are twice as large as those of females and may span 50 ha (124 ac).[16]

Saltmarsh sparrows are promiscuous, and the majority of broods exhibit mixed parentage.[17] During the nesting season, males roam long distances chasing and mounting females regardless of receptivity. Only females exhibit parental care, building the nest, incubating the eggs, and providing food to the young.[9] The nest is an open cup constructed of grass, usually attached to saltmeadow cordgrass (Spartina patens) or saltmarsh rush (Juncus gerardii) at a height of 6–15 cm (2.4–5.9 in). Clutch size is 3 to 5. Incubation begins after the last egg is laid and takes 11–12 days. Young fledge 8–11 days after hatching but remain dependent on the mother for an additional 15–20 days.[13]

The primary cause of nest mortality is flooding due to storm surges and periodic, exceptionally high spring tides which occur every 28 days during the new moon. The saltmarsh sparrow exhibits several adaptations to flooding, including nest repair, egg retrieval, rapid re-nesting, and synchronization of breeding with the lunar cycle.[18][19] Nesting begins immediately following a spring tide, allowing young to fledge before the next spring tide.[19] Two broods are typically raised per breeding season.[13]

Conservation status

The saltmarsh sparrow is of high conservation concern due to habitat loss resulting in small fragmented populations.[13][20] Salt marshes are one of the most threatened habitats worldwide due to their limited natural extent, long history of human modification, and anticipated sea level rise.[21] The spread of the invasive reed Phragmites has also contributed to habitat loss.[22] The saltmarsh sparrow is very sensitive to sea level rise because of the role of flooding in nest mortality.[23] In addition, the saltmarsh sparrow is particularly susceptible to mercury bioaccumulation, but the effects of this on survival are unclear.[24][25][26]

Saltmarsh sparrow populations declined between 5% and 9% per year between the 1990s and 2010s, resulting in a total decline of over 75%.[13][27] Without management intervention, the saltmarsh sparrow is projected to become extinct by 2050.[13] The saltmarsh sparrow was listed on the 2016 State of North America's Birds Watch List with a concern score of 19 out of 20,[28] and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is currently undertaking a status review to determine whether the species should be listed under the Endangered Species Act.[29] Its total population was estimated to be 53,000 in 2016.[30]

References

- BirdLife International. 2018. Ammospiza caudacuta. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22721129A131887480. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22721129A131887480.en. Downloaded on 31 December 2018.

- "Saltmarsh Sparrow, Life History, All About Birds - Cornell Lab of Ornithology". Allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (1992), ISBN 978-0849342585.

- 1961-, Sibley, David (2003). The Sibley field guide to birds of eastern North America (1st ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780679451204. OCLC 52075784.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Beedy, Edward C.; Pandolfino, Edward R. (2013-06-17). Birds of the Sierra Nevada: Their Natural History, Status, and Distribution. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520274938.

- Robins, Jerome D.; Schnell, Gary D. (1971). "Skeletal Analysis of the Ammodramus-ammospiza Grassland Sparrow Complex: A Numerical Taxonomic Study". The Auk. 88 (3): 567–590. JSTOR 4083751.

- Zink, Robert M.; Avise, John C. (1990-06-01). "Patterns of Mitochondrial DNA and Allozyme Evolution in the Avian Genus Ammodramus". Systematic Zoology. 39 (2): 148–161. doi:10.2307/2992452. ISSN 1063-5157. JSTOR 2992452.

- Rising, James D.; Avise, John C. (1993). "Application of Genealogical-Concordance Principles to the Taxonomy and Evolutionary History of the Sharp-Tailed Sparrow (Ammodramus caudacutus)". The Auk. 110 (4): 844–856. doi:10.2307/4088638. JSTOR 4088638.

- Greenlaw, Jon S. (1993). "Behavioral and Morphological Diversification in Sharp-Tailed Sparrows (Ammodramus caudacutus) of the Atlantic Coast". The Auk. 110 (2): 286–303. JSTOR 4088557.

- Shriver, W. Gregory; Gibbs, James P.; Vickery, Peter D.; Gibbs, H. Lisle; Hodgman, Thomas P.; Jones, Peter T.; Jacques, Christopher N.; Fleischer, R. C. (2005-01-01). "Concordance between morphological and molecular markers in assessing hybridization between sharp-tailed sparrows in new england". The Auk. 122 (1): 94–107. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2005)122[0094:CBMAMM]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0004-8038.

- Walsh, Jennifer; Kovach, Adrienne I.; Lane, Oksana P.; O'Brien, Kathleen M.; Babbitt, Kimberly J. (2011-05-19). "Genetic Barcode RFLP Analysis of the Nelson's and Saltmarsh Sparrow Hybrid Zone". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 123 (2): 316–322. doi:10.1676/10-134.1. ISSN 1559-4491.

- Smith, Fletcher M. (2011). "Photo Essay: Subspecies of Saltmarsh Sparrow and Nelson's Sparrow" (PDF). North American Birds. 65 (2): 368–377.

- GREENLAW, JON S.; RISING, JAMES D. (1994). "Saltmarsh Sharp-tailed Sparrow (Ammodramus caudacutus)". The Birds of North America Online. doi:10.2173/bna.112.

- Greenlaw, Jon S.; Woolfenden, Glen E. (2007-09-01). "Wintering distributions and migration of saltmarsh and nelson's sharp-tailed sparrows". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 119 (3): 361–377. doi:10.1676/05-152.1. ISSN 1559-4491.

- Post, William; Greenlaw, Jon S. (2006-10-01). "Nestling diets of coexisting salt marsh sparrows: Opportunism in a food-rich environment". Estuaries and Coasts. 29 (5): 765–775. doi:10.1007/BF02786527. ISSN 1559-2723.

- Shriver, W. Gregory; Hodgman, Thomas P.; Gibbs, James P.; Vickery, Peter D. (2010-05-12). "Home Range Sizes and Habitat Use of Nelson's and Saltmarsh Sparrows". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 122 (2): 340–345. doi:10.1676/09-149.1. ISSN 1559-4491.

- Hill, Christopher E.; Gjerdrum, Carina; Elphick, Chris S. (2010-04-01). "Extreme Levels of Multiple Mating Characterize the Mating System of the Saltmarsh Sparrow (Ammodramus caudacutus)". The Auk. 127 (2): 300–307. doi:10.1525/auk.2009.09055. ISSN 0004-8038.

- Gjerdrum, Carina; Elphick, Chris S.; Rubega, Margaret (2005-11-01). "Nest site selection and nesting success in saltmarsh breeding sparrows: the importance of nest habitat, timing, and study site differences". The Condor. 107 (4): 849–862. doi:10.1650/7723.1. ISSN 0010-5422.

- Shriver, W. Gregory; Vickery, Peter D.; Hodgman, Thomas P.; Gibbs, James P.; Sandercock, B. K. (2007-04-01). "Flood tides affect breeding ecology of two sympatric sharp-tailed sparrows". The Auk. 124 (2): 552–560. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2007)124[552:FTABEO]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0004-8038.

- DiQuinzio, Deborah A.; Paton, Peter W. C.; Eddleman, William R.; Brawn, J. (2001-10-01). "Site fidelity, philopatry, and survival of promiscuous saltmarsh sharp-tailed sparrows in rhode island". The Auk. 118 (4): 888–899. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2001)118[0888:SFPASO]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0004-8038.

- Gedan, K. Bromberg; Silliman, B. R.; Bertness, M. D. (2009). "Centuries of Human-Driven Change in Salt Marsh Ecosystems". Annual Review of Marine Science. 1 (1): 117–141. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.319.6842. doi:10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163930. PMID 21141032.

- Benoit, Lori K.; Askins, Robert A. (1999-03-01). "Impact of the spread ofPhragmites on the distribution of birds in Connecticut tidal marshes". Wetlands. 19 (1): 194–208. doi:10.1007/BF03161749. ISSN 0277-5212.

- Bayard, Trina S.; Elphick, Chris S. (2011-04-01). "Planning for Sea-Level Rise: Quantifying Patterns of Saltmarsh Sparrow (Ammodramus Caudacutus) Nest Flooding Under Current Sea-Level Conditions". The Auk. 128 (2): 393–403. doi:10.1525/auk.2011.10178. ISSN 0004-8038.

- Lane, Oksana P.; O’Brien, Kathleen M.; Evers, David C.; Hodgman, Thomas P.; Major, Andrew; Pau, Nancy; Ducey, Mark J.; Taylor, Robert; Perry, Deborah (2011-11-01). "Mercury in breeding saltmarsh sparrows (Ammodramus caudacutus caudacutus)". Ecotoxicology. 20 (8): 1984–91. doi:10.1007/s10646-011-0740-z. ISSN 0963-9292. PMID 21792662.

- Cristol, Daniel A.; Smith, Fletcher M.; Varian-Ramos, Claire W.; Watts, Bryan D. (2011-11-01). "Mercury levels of Nelson's and saltmarsh sparrows at wintering grounds in Virginia, USA". Ecotoxicology. 20 (8): 1773–1779. doi:10.1007/s10646-011-0710-5. ISSN 0963-9292. PMID 21698442.

- Winder, Virginia L. (2012-09-04). "Characterization of Mercury and Its Risk in Nelson's, Saltmarsh, and Seaside Sparrows". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e44446. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044446. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3433451. PMID 22962614.

- Shriver, W. Gregory; O’Brien, Kathleen M.; Ducey, Mark J.; Hodgman, Thomas P. (2016-01-01). "Population abundance and trends of Saltmarsh (Ammodramus caudacutus) and Nelson's (A. nelsoni) Sparrows: influence of sea levels and precipitation". Journal of Ornithology. 157 (1): 189–200. doi:10.1007/s10336-015-1266-6. ISSN 2193-7192.

- "Species Assessment Summary and Watch List". State of North America's Birds 2016. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2017). "Sharp Tailed Saltmarsh Sparrow Peer Review Plan" (PDF).

- Wiest, Whitney A.; Correll, Maureen D.; Olsen, Brian J.; Elphick, Chris S.; Hodgman, Thomas P.; Curson, David R.; Shriver, W. Gregory (2016-03-16). "Population estimates for tidal marsh birds of high conservation concern in the northeastern USA from a design-based survey". The Condor. 118 (2): 274–288. doi:10.1650/CONDOR-15-30.1. ISSN 0010-5422.

Further reading

Book

- Greenlaw, J. S. and J. D. Rising. 1994. Sharp-tailed Sparrow (Ammodramus caudacutus). In The Birds of North America, No. 112 (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds.). Philadelphia: The Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, D.C.: The American Ornithologists’ Union.

Articles

- Benoit LK & Askins RA. (2002). Relationship between habitat area and the distribution of tidal marsh birds. Wilson Bulletin. vol 114, no 3. p. 314-323.

- Chan YL, Hill CE, Maldonado JE & Fleischer RC. (2006). Evolution and conservation of tidal-marsh vertebrates: Molecular approaches. Studies in Avian Biology. vol 32, p. 54-75.

- Conway CJ & Droege S. (2006). A unified strategy for monitoring changes in abundance of birds associated with North American tidal marshes. Studies in Avian Biology. vol 32, p. 282-297.

- DiQuinzio DA, Paton PWC & Eddleman WR. (2002). Nesting ecology of saltmarsh sharp-tailed sparrows in a tidally restricted salt marsh. Wetlands. vol 22, no 1. p. 179-185.

- Erwin RM, Cahoon DR, Prosser DJ, Sanders GM & Hensel P. (2006). Surface elevation dynamics in vegetated Spartina marshes versus unvegetated tidal ponds along the mid-Atlantic coast, USA, with implications to waterbirds. Estuaries & Coasts. vol 29, no 1. p. 96-106.

- Erwin RM, Sanders GM & Prosser DJ. (2004). Changes in lagoonal marsh morphology at selected northeastern Atlantic coast sites of significance to migratory waterbirds. Wetlands. vol 24, no 4. p. 891-903.

- Erwin RM, Sanders GM, Prosser DJ & Cahoon DR. (2006). High tides and rising seas: Potential effects on estuarine waterbirds. Studies in Avian Biology. vol 32, p. 214-228.

- Fry AJ. (1999). Mildly deleterious mutations in avian mitochondrial DNA: Evidence from neutrality tests. Evolution. vol 53, no 5. p. 1617-1620.

- Grenier JL & Greenberg R. (2006). Trophic adaptations in sparrows and other vertebrates of tidal marshes. Studies in Avian Biology. vol 32, p. 130-139.

- Hanowski JM & Niemi GJ. (1990). "An Approach for Quantifying Habitat Characteristics for Rare Wetland Birds". In Mitchell, R S, C J Sheviak and D J Leopold (Ed) New York State Museum Bulletin, No 471 Ecosystem Management: Rare Species and Significant Habitats; 15th Annual Natural Areas Conference and 10th Annual Meeting of the Natural Areas Association, Syracuse, New York, USA, June 6–9, 1988 Ix+314p New York State Museum: Albany, New York, USA Illus Maps Paper 51–56, 1990.

- Hodgman TP, Shriver WG & Vickery PD. (2002). Redefining range overlap between the Sharp-tailed Sparrows of coastal New England. Wilson Bulletin. vol 114, no 1. p. 38-43.

- Patten MA & Radamaker K. (1991). A Fall Record of the Sharp-Tailed Sparrow for Interior California USA. Western Birds. vol 22, no 1. p. 37-38.

- Post W. (1998). The status of Nelson's and saltmarsh sharp-tailed sparrows on Waccasassa Bay, Levy County, Florida. Florida Field Naturalist. vol 26, no 1. p. 1-6.