San Francisco housing shortage

Starting in the 1990s, the city of San Francisco, and the surrounding San Francisco Bay Area have faced a serious affordable housing shortage, such that by October 2015, San Francisco had the highest rents of any major US city.[2] The nearby city of San Jose, had the fourth highest rents, and adjacent Oakland, had the sixth highest.[2] Over the period April 2012 to December 2017, the median house price in most counties in the Bay Area nearly doubled.[3] Late San Francisco mayor Ed Lee has called the shortage a "housing crisis",[4] and news reports stated that addressing the shortage was the mayor's "top priority".[5]

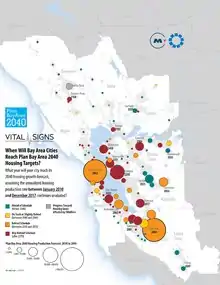

"Every single county is over-performing its job forecast, some by massive amounts, and every single county is under-performing its housing forecast, almost all by a wide margin," MTC director Steve Heminger said in his report to the Association of Bay Area Governments executive board last month.[1]

Causes

Since the 1960s, San Francisco and the surrounding Bay Area have enacted strict zoning regulations.[6] Among other restrictions, San Francisco does not allow buildings over 40 feet tall in most of the city, and has passed laws making it easier for neighbors to block developments.[7] Partly as a result of these codes, from 2007 to 2014, the Bay Area issued building permits for only half the number of needed houses, based on the area's population growth.[8] At the same time, there has been rapid economic growth of the high tech industry in San Francisco and nearby Silicon Valley, which has created hundreds of thousands of new jobs. The resultant high demand for housing, combined with the lack of supply, (caused by severe restrictions on the building of new housing units[9]) have caused dramatic increases in rents and extremely high housing prices.[10][11][12] For example, from 2012 to 2016, the San Francisco metropolitan area added 373,000 new jobs, but permitted only 58,000 new housing units.[13]

Effects

The city of San Francisco has strict rent control laws.[14] However, a California state law called the Ellis Act allows landlords to evict rent-controlled tenants by going out of business, and fully exiting the rental market. Hundreds of tenants have been evicted through the Ellis Act process.[15]

Due to the advances of the city's economy from the increase of tourism, the boom of innovative tech companies, and insufficient new housing production, the rent increased by more than 50 percent by the 1990s. [16][17]Many affluent tech workers migrated to San Francisco due job opportunities and lack of housing in the South Bay.[17] Until the end of the 1960s, San Francisco had affordable housing, which allowed people from many different backgrounds to settle down, but the economic shift impacted the city's demographics.[16] All of this resulted in constant gentrification of many neighborhoods. [18] Residents of areas such as the Tenderloin and The Mission District, which house many immigrants and low-income families, are faced with the possibility of eviction, in order to develop low-income housing to more luxurious housing, which caters to the advances of the economy. [18] For example, residents of the Mission District, constituting 5 percent of the city's population, experienced 14 percent of the citywide evictions in the year 2000. [19]

The effect of housing policies has been to discourage migration to California, especially San Francisco and other coastal areas, as the California Legislative Analyst's Office 2015 report "California's High Housing Costs - Causes and Consequences" details: [From 1980-2010]

"If California had added 210,000 new housing units each year over the past three decades (as opposed to 120,000), [enough to keep California's housing prices no more than 80% higher than the median for the U.S. as a whole--the price differential which existed in 1980] population would be much greater than it is today.

We estimate that around 7 million additional people would be living in California.

In some areas, particularly the Bay Area, population increases would be dramatic. For example,

San Francisco's population would be more than twice as large (1.7 million people versus around 800,000)."[20]

Responses

Housing has become a key political issue in Bay Area elections. In November 2015, San Francisco voters rejected two ballot propositions both of which were claimed by their supporters to reduce the crisis. The first, Proposition F, would have enacted a number of restrictions on Airbnb rentals within the city. The second, Proposition I or the "Mission Moratorium", would have blocked all housing development in San Francisco's Mission District for 18 months, except for developments in which every apartment was subsidized at a below-market rate.[21]

To address evictions, San Francisco City Supervisor David Campos (D9) passed two new city ordinances, each requiring landlords to pay tens of thousands of dollars to each tenant evicted under the Ellis Act. The first ordinance was struck down as unconstitutional under the Fifth Amendment,[22] while the second was rejected as contrary to California state law.[23]

Mayor Ed Lee responded to the shortage by calling for the construction of 30,000 new housing units by 2020, and proposing a $310 million city bond to fund below-market-rate housing units.[24] The goal of 30,000 new units was approved by San Francisco voters in 2014's Proposition K,[25] and the affordable housing bond was passed in 2015 as Proposition A.[26]

Then City Supervisor Scott Wiener (D8) has criticized the advocates of anti-development laws, writing an article titled "Yes, Supply & Demand Apply to Housing, Even in San Francisco" in response to Proposition I. Wiener called for greatly increasing the supply of all housing, including both subsidized housing and housing at market rate.[27]

References

- Ioannou, Filipa (2018-06-28). "It'll take this Bay Area city 966 years to meet its 22-year housing goal". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2018-07-06. Retrieved 2018-08-20.

- Elsen, Tracy (September 3, 2015). "San Francisco's Median Rent Hits Yet Another New High". SF Curbed. Archived from the original on 2016-02-26. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- "Bay Area homes deliver record-breaking returns". The Mercury News. 2018-02-28. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- Coté, John (January 17, 2014). "Sneak peek: Mayor Ed Lee has a housing solution". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2014-02-03. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Tyler, Carolyn (January 15, 2015). "San Francisco mayor focuses on housing crisis in State of City speech". ABC 7 News. Archived from the original on 2015-03-25. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Smith, Matt (August 18, 1999). "Welcome Home". SF Weekly. Archived from the original on October 1, 2000. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Russel, Kyle (April 8, 2014). "This One Intersection Explains Why Housing Is So Expensive In San Francisco". Business Insider. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Weinberg, Cory (Apr 13, 2015). "Did your city fail the Bay Area's housing supply test? Probably". San Francisco Business Times. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Torres, Blanca (2017-04-28). "Housing's tale of two cities: Seattle builds, S.F. lags". San Francisco Business Times. Archived from the original on 2017-05-02. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

So how can smaller Seattle make so much more housing happen than San Francisco? Developers active in both cities and officials who have worked in both point to structural differences that outweigh the demographic similarities. In San Francisco, development issues are routinely subject to consideration by neighborhood bodies, approval by the city planning commission and often ratification by its board of supervisors, with opportunities for decisions to be appealed. Seattle's approval process is much more streamlined ... The city's planning commission is strictly a policy entity. It does not approve or reject projects. The city council weighs in on projects only in rare cases. [In S.F.] ... he thinks that the California Environmental Quality Act, known as CEQA, makes it too easy for residents to sue projects, effectively holding them up for years or blocking them.

- Lee, Wendy (September 21, 2015). "Tech bus drivers forced to live in cars to make ends meet". SF Chronicle. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Cutler, Kim-Mai (Apr 14, 2014). "How Burrowing Owls Lead To Vomiting Anarchists (Or SF's Housing Crisis Explained)". TechCrunch. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Cutler, Kim-Mai (Nov 2, 2014). "So You Want To Fix The Housing Crisis". TechCrunch. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Clark, Patrick (2017-06-23). "Why Can't They Build More Homes Where the Jobs Are?". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2017-08-28. Retrieved 2017-12-01.

San Francisco's metropolitan area added 373,000 net new jobs in the last five years—but issued permits for only 58,000 units of new housing. The lack of new construction has exacerbated housing costs in the Bay Area, making the San Francisco metro among the cruelest markets in the U.S. Over the same period, Houston added 346,000 jobs and permitted 260,000 new dwellings, five times as many units per new job as San Francisco.

- Erwert, Anna Marie (August 25, 2015). "The best and worst of San Francisco's rent control". SF Chronicle. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Chuang, Stephanie (October 24, 2013). "Ellis Act Evictions Rising in San Francisco". NBC Bay Area. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Whittle, Henry J.; Palar, Kartika; Hufstedler, Lee Lemus; Seligman, Hilary K.; Frongillo, Edward A.; Weiser, Sheri D. (2015). "Food insecurity, chronic illness, and gentrification in the San Francisco Bay Area: An example of structural violence in United States public policy". Social Science & Medicine. 143: 154–161. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.027. PMID 26356827.

- Shaw, Randy (2018). "Who Gets to Live in the New Urban America". Generation Priced Out: Who Gets to Live in the New Urban America (1 ed.). University of California Press. doi:10.1525/j.ctv5cgbsh.5 (inactive 2021-01-10). ISBN 9780520299122. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctv5cgbsh.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- Robinson, Tony (1995). "SAGE Journals: Your gateway to world-class journal research". Urban Affairs Quarterly. 30 (4): 483–513. doi:10.1177/107808749503000401. S2CID 153614015.

- Pamuk, Ayse (2004-06-01). "Geography of immigrant clusters in global cities: a case study of San Francisco". International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 28 (2): 287–307. doi:10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00520.x. ISSN 1468-2427.

- Taylor, Mac (2015-03-17). California's High Housing Costs - Causes and Consequences (PDF) (Report). CA Legislative Analysts Office. pp. 20, 23. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-06. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

- Khan, Naureen (November 4, 2015). "After failed propositions, San Francisco housing crisis still festering". Al Jazeera America. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Egelko, Bob (October 22, 2014). "Judge tosses S.F. law meant to shield evicted tenants". SF Chronicle. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Egelko, Bob (October 7, 2015). "Judge strikes down San Francisco eviction law". SF Chronicle. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Johnson, Lizzie (October 2, 2015). "Is Mayor Lee's housing bond enough to crack this S.F. crisis?". SF Chronicle. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- "California Election Watch 2014: Bay Area Measures We're Following". KQED News. November 5, 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Brooks, John (November 4, 2015). "S.F. Election: Lee Re-elected, Peskin Wins, Airbnb Curbs Fail". KQED News. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Wiener, Scott (2015-02-20). "Yes, Supply & Demand Apply to Housing, Even in San Francisco". Medium. Retrieved 23 December 2015.