Schaerbeek

Schaerbeek (obsolete Dutch spelling, retained in French, pronounced [skaʁbek] (![]() listen)) or Schaarbeek (Dutch, pronounced [ˈsxaːrbeːk] (

listen)) or Schaarbeek (Dutch, pronounced [ˈsxaːrbeːk] (![]() listen)) is one of the 19 municipalities of the Brussels-Capital Region (Belgium). Located in the north-eastern part of the region, it is bordered by the City of Brussels, Etterbeek, Evere and Saint-Josse-ten-Noode. In common with all of Brussels' municipalities, it is legally bilingual (French–Dutch).

listen)) is one of the 19 municipalities of the Brussels-Capital Region (Belgium). Located in the north-eastern part of the region, it is bordered by the City of Brussels, Etterbeek, Evere and Saint-Josse-ten-Noode. In common with all of Brussels' municipalities, it is legally bilingual (French–Dutch).

Schaerbeek

| |

|---|---|

_-_2264-0007-0.jpg.webp) Schaerbeek Town Hall | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

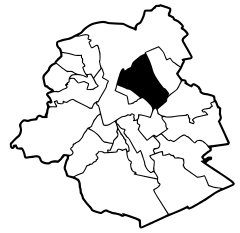

Schaerbeek Location in Belgium

Schaerbeek municipality in the Brussels-Capital Region  | |

| Coordinates: 50°52′N 04°23′E | |

| Country | Belgium |

| Community | Flemish Community French Community |

| Region | Brussels |

| Arrondissement | Brussels |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Bernard Clerfayt (FDF) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8.14 km2 (3.14 sq mi) |

| Population (2018-01-01)[1] | |

| • Total | 133,010 |

| • Density | 16,000/km2 (42,000/sq mi) |

| Postal codes | 1030 |

| Area codes | 02 |

| Website | www.schaerbeek.be |

As of 1 December 2019, Schaerbeek had a total population of 132,861 inhabitants, 66,010 men and 66,851 women, for an area of 8.14 km2 (3.14 sq mi), which gives a population density of 16,322/km2 (42,270/sq mi).

The eastern part of Schaerbeek (the area that includes Vergote Square, Boulevard Lambermont/Lambermontlaan, the Fleurs Quarter, Jamblinne de Meux Square, the Diamant Quarter and Josaphat Park) is a affluent area noted for its architecture and its convenient location (close to the EU institutions and the financial heart of the city, as well as NATO's headquarters in the neighbouring municipality of Evere).

The western part of Schaerbeek (the area near the Brussels-North railway station, Chaussée de Haecht/Haachtsesteenweg and the Van Praet bridge) is home to Brussels' large Belgian Turkish community. The area around St. Mary's Royal Church is dubbed "Little Anatolia" because of all the Turkish restaurants and shops on Chaussée de Haecht.[2] The area is also home to a significant Belgian Moroccan population and other immigrant communities such as Spanish, Congolese, and Asian immigrants. However, the district offers a social blend because of the numerous schools like the Hogeschool Sint-Lukas Brussel, the municipal administrations and the proximity of Rue Royale/Koningsstraat.[3]

The Schaerbeek Cemetery, despite its name, is actually located in Evere.

Toponymy

Etymology

The first mention of Schaerbeek's name was Scarenbecca, recorded in a document from the Bishop of Cambrai in 1120.[4] The origin of the name may come from the Franconian (Old Dutch) words schaer ("notch", "score") and beek ("creek").[5]

Schaerbeek is nicknamed "the city of donkeys" (French: la cité des ânes, Dutch: de ezelsgemeente). This name is reminiscent of times when people of Schaerbeek, who were cultivators of sour cherries primarily for Kriek production, would arrive at the Brussels marketplace with donkeys laden with sour cherries. Donkeys are still kept in Josaphat Park, and sour cherry trees line the streets of the Diamant Quarter of Schaerbeek (Avenue Milcamps/Milcampslaan, Avenue Émile Max/Émile Maxlaan, and Avenue Opale/Opaallaan). The Square des Griottiers/Morelleboomsquare is named after these trees.

History

Antiquity and Middle Ages

The period at which human activity started in Schaerbeek can be inferred from the Stone Age flint tools that were recovered in the Josaphat valley. Tombs and coins dating from the reign of Roman Emperor Hadrian (2nd century) were also found near the old Roman roads that crossed Schaerbeek's territory.

The first mention of the town's name appears in a legal document dated 1120, whereby the Bishop of Cambrai granted the administration of the churches of Scarenbecca and Everna (today's neighbouring Evere) to the canons of Soignies. Politically, the town was part of the Duchy of Brabant. In 1301, John II, Duke of Brabant, had the town administered by the schepen (aldermen) of Brussels. A new church to Saint Servatius was built around that same time, at the same location as the old church.

At the end of the 14th century, the Schaerbeek lands that belonged to the Lords of Kraainem were sold and reconverted into a hunting ground. The official entry of the visiting Dukes of Burgundy into Brussels, their second capital, was also through Schaerbeek, where they had to swear to uphold the city's privileges. The game reservation and the rural character of the village lasted until the end of the 18th century. The areas not covered by woods were used to cultivate vegetables and grow vines. In 1540, Schaerbeek counted 112 houses and 600 inhabitants.

16th–19th centuries

Up until the 16th century, the village had lived in relative peace. This would change in the middle of the 16th century as the Reformation set in. Schaerbeek suffered through ravages and destruction about a dozen times over the following two centuries, starting in the 1570s with William the Silent's mercenary troops fighting the Catholic Duke of Alba. Spanish, French, British, and Bavarian troops all came through Schaerbeek, with the usual exactions and requisitions inflicted on the population.

After the French Revolution, it was decreed that Schaerbeek would be taken away from Brussels and proclaimed an independent commune, with its own mayor, schepen, and municipal assembly.

On 27 September 1830, during the Belgian Revolution, some fighting occurred in the Josaphat valley between the revolutionary troops and the retreating Dutch troops.

In 1879, a more modern St. Servatius Church was built near the old one, which was eventually demolished in 1905.[6] The Town Hall and Schaerbeek railway station were built in 1887 and 1902, respectively. In 1889, the shooting range known as the Tir national was established.

At the end of the 19th and in the early 20th centuries, Schaerbeek became home to the gentry. Avenue Louis Bertrand/Louis Bertrandlaan was laid out to herald a new, tree-filled residential district for the city's burgeoning middle classes, many of whom employed the period's best architects to design their new homes. Gustave Strauven, Franz Hemelsoet and Henri Jacobs were just three of the architects who reinvented family houses, apartment buildings and educational buildings in the Art Nouveau style.

20th and 21st centuries

In 1904, the newly landscaped Josaphat Park was inaugurated.[6] One year later, the old St. Servatius Church, the last witness to Schaerbeek's medieval past, was demolished.[6]

In 1915, the British nurse Edith Cavell was executed by an occupying German Army firing squad at the Tir national.

Dwight D. Eisenhower came to visit the municipality at the close of World War II. Five years later, the population of Schaerbeek peaked at 125,000 inhabitants.[6]

Nowadays, the city is governed by a liberal-ecologist majority, after a disputed run between Bernard Clerfayt (FDF) and Laurette Onkelinx (PS).

2003 election incident

In the federal election of 18 May 2003, one candidate received 4,096 unexplained extra votes. After an inquiry, the anomaly was attributed to a single event upset in an electronic voting machine, presumably caused by an ionising particle.[7][8]

2016 terrorist attacks

On the morning of 22 March 2016, three coordinated bombings occurred in Belgium in which the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) claimed responsibility. In these attacks, at least 31 victims and two suicide bombers were killed, and 300 other people were injured.[9] Hours after the attacks, police were pointed to a home in Schaerbeek by the taxi driver who drove the suspects to Brussels Airport.[10] They raided the home and found a nail bomb, 15 kg (33 lb) of acetone peroxide, hydrogen peroxide, and an ISIL flag.[11] Inside a waste container near the house, they also found a computer belonging to Ibrahim El Bakraoui who is believed to have carried out suicide bombings during the attacks along with his brother.[12]

Nearly seven months later, on 5 October, three police officers were attacked by a man with a camping knife in Schaerbeek. Two of them suffered stab wounds, while the third was physically assaulted but otherwise uninjured. The assailant was then shot in the leg, subdued, and taken to hospital for medical treatment.[13] He was charged with attempted terrorism-related murder but the court did not see these charges proven. He was convicted to a nine-year prison sentence for assault and battery.[14]

Demographics

Schaerbeek has a large concentration of immigrants from other countries, and their children, including many of Turkish ancestry, a significant part of which originates from Afyon or Emirdağ, Turkey.

As of 2016, the largest share of Muslims in Schaerbeek are of Moroccan origin, but there are also Albanians and Turks. There are as non-Muslim foreign populations such as Congolese, Bulgarians, Polish, and Romanians. Mayor of Schaerbeek Bernard Clerfayt argued that the diversity in the foreign population means there is a lack of a ghetto effect, and Molenbeek mayor Françoise Schepmans stated that the foreigner population in Schaerbeek was more diverse than that of Molenbeek.[3]

As of 2016, 22% of young people in Schaerbeek are unemployed. The municipality is in an area of Brussels called the "poor croissant".[3]

Education

Public communal French-language secondary schools include:[15]

- Athénée Fernand Blum, a traditional gateway to the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB)

- Institut communal d'enseignement technique Frans Fischer

- Lycée Emile Max

French-language subsidised religious secondary schools include:[16]

- Centre scolaire Sainte-Marie La Sagesse

- Collège Roi Baudouin

- Institut de la Saint-Famille d'Helmet

- Collège Roi Baudouin Enseignement technique et professionnel

- Institut Technique Cardinal Mercié-Notre-Dame du Sacré-Coeur

- Institut Saint-Dominique

- Institut de la Vierge Fidèle

Koninklijk Atheneum Emmanuel Hiel serves as the public Dutch-language secondary school in Schaerbeek, operated by the Flemish Community of Belgium.[17]

Sights

- Schaerbeek counts a number of Art Deco and Art Nouveau houses, including the Autrique House, the first house built by Victor Horta in the Brussels area.

- The impressive Town Hall was inaugurated by King Leopold II in 1887.

- Josaphat Park, also inaugurated by King Leopold II (in 1904), provides a haven of quiet in the heart of the city. It is bordered by the Brusilia Residence, the tallest residential building in Belgium.

- Schaerbeek railway station, where the new national railway museum of Belgium, Train World, opened in 2015.

- St. Mary's Royal Church, an eclectic Roman Catholic church built between 1845 and 1888, which has been listed as a protected monument since 1976.[18]

- The Clockarium is a clock museum. There is also a beer museum and a mechanical organ museum nearby.

Terdelt Garden City

Terdelt Garden City

Brusilia Residence

Brusilia Residence

Famous inhabitants

- Henry Le Bœuf, banker and patron of the arts (1874–1935)

- Jacques Brel, famous Belgian singer (1929–1978)

- Paul-Henri Spaak, politician and statesman (1899–1972)

- René Magritte, surrealist painter (1898–1967)

- Nicolas Colsaerts, European Tour professional golfer (b. 1982)

- Paul Deschanel, French statesman and President of France (1855–1922)

- Michel de Ghelderode, novelist (1898–1962), employed at the Townhall from 1923 to 1946

- Virginie Efira, cinema actress and television presenter (b. 1977)

- Georges Eekhoud, novelist (1854–1927)

- Camille Jenatzy, race car driver (1868–1913)

- Jan Ferguut, novelist (1835–1902)

- Gustave Strauven, Art Nouveau architect (1878–1919)

- Franz Hemelsoet, Art Nouveau architect (1875–1947)

- Henri Jacobs, Art Nouveau architect (1864–1935)

- Andrée de Jongh, member of the Resistance during World War II (1916–2007)

- Monique de Bissy, member of the Resistance during World War II (1923–2009)

- Todor Angelov, member of the Resistance during World War II (1900–1943)

- Roger Somville, painter (b. 1923)

- Jean Roba, comics author, creator of Boule et Bill (1930–2006)

- Rob Redding, American media proprietor and abstract artist (b. 1976)

- Roger Camille, cartoonist (1936–2006)

- Claude Coppens, pianist and composer (b. 1936)

- Alain Hutchinson, politician (b. 1949)

- Raymond van het Groenewoud, musician and singer (b. 1950)

- Daniel Ducarme, politician (b. 1954)

- Emilio Ferrera, football player and coach (b. 1967)

- Maurane, singer (b. 1960)

- François Schuiten (b. 1956), comics author

- Agustín Goovaerts, architect (b. 1885)

- Jan Cornelis Hofman, Post-Impressionist painter, died there in 1966

- Georges Grun, former football player (b. 1962)

- Anca Parghel, jazz singer, lived on Avenue Paul Deschanel/Paul Deschanellaan, occasionally giving private piano and canto lessons to aspiring young singers and musicians.

Twin cities

.svg.png.webp) Houffalize, Belgium – At the end of World War II, Schaerbeek collected funds to relieve Houffalize, suffering heavily from the last German counter-attack in the Ardennes. Since then, Houffalize yearly sends hundreds of Christmas trees to Schaerbeek.

Houffalize, Belgium – At the end of World War II, Schaerbeek collected funds to relieve Houffalize, suffering heavily from the last German counter-attack in the Ardennes. Since then, Houffalize yearly sends hundreds of Christmas trees to Schaerbeek. Al-Hoceima, Morocco

Al-Hoceima, Morocco Beyoğlu, Turkey

Beyoğlu, Turkey Prairie Village, Kansas, United States

Prairie Village, Kansas, United States Dardania, Kosovo

Dardania, Kosovo.svg.png.webp) Quebec City, Canada

Quebec City, Canada Vicovu de Sus, Romania

Vicovu de Sus, Romania Anyang, China

Anyang, China

References

- "Wettelijke Bevolking per gemeente op 1 januari 2018". Statbel. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- "Promenades découvertes de Schaerbeek : Parcours 1: les abords de la place de la Reine" (pdf) (in French). Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- Capadites, Christina (11 April 2016). "Molenbeek and Schaerbeek: A tale of two tragedies". CBS News. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "Enquete Communale – Final". Scribd.com. 31 August 2009. Archived from the original on 30 January 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- "Schaerbeek au fil du temps | Schaerbeek". Schaerbeek 1030 Schaarbeek (in French). Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "Rapport concernant les élections du 18 mai 2003" (5.3.7 L’incident de Schaerbeek) (in French). PourEVA. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Ferreira, Becky (17 February 2017). "How Space Weather Can Influence Elections on Earth". Motherboard.

- "Another bomb found in Brussels after attacks kill at least 34; Islamic State claims responsibility". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- David Lawler; Danny Boyle (22 March 2016). "Brussels attacks: 34 killed and hundreds wounded as Islamic State claims responsibility for airport and Metro bombings – live". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- "Eén verdachte wordt momenteel ondervraagd". Gazet van Antwerpen. 23 March 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- Alastair Jamieson; Annick M'Kele (23 March 2016). "Brussels Attacks: El Bakraoui Brothers Were Jailed for Carjackings, Shootout". NBC News. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- Samuel, Henry (5 October 2016). "Two policemen injured in Brussels stabbing in suspected terror attack". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- Aanval op twee agenten geen terreurdaad en geen moordpoging, maar dader veroordeeld tot 9 jaar cel”

- "Réseau communal." Schaerbeek. Retrieved on September 12, 2016.

- "Réseau Libre et communauté française." Schaerbeek. Retrieved on September 12, 2016.

- "Enseignement néerlandophone"/"Nederlandstalig onderwijs Archived 11 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine." Schaerbeek. Retrieved on September 12, 2016.

- "Schaerbeek - Église Sainte-Marie - Place de la Reine - VAN OVERSTRAETEN Henri Désiré Louis". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Schaerbeek. |

- Official site of Schaerbeek municipality (in French, Dutch and English)

- Site of Burgmester Bernard Clerfayt

- Committee of Federated Suburbs of Schaerbeek

- Social harmonisation of Schaerbeek – carte sociale

- Local libraries

- Police zone site – 5344 (Evere-Saint-Josse-Schaerbeek)

- CHU Brugmann – site Paul Brien