Sefer Bey Zanuqo

Sefer Bey Zanuqo[1] (Adyghe: Занэкъо Сэфэрбий, romanized: Zanəqo Səfərbiy; Ottoman Turkish: ظنزادە صفر بك, romanized: Žanzade Sefer Bek) (? – 1 January 1860) was a Circassian nobleman,[2] military commander, diplomat[3] and independence activist.[3] He took part in the various stages of the Russo-Circassian War both in a military and a political capacity. Advocating for the cause of Circassian independence in the west and acting as an emissary of the Ottoman Empire in the region. By the end of his life Zanuqo had emerged as the leader of the Circassian independence movement.

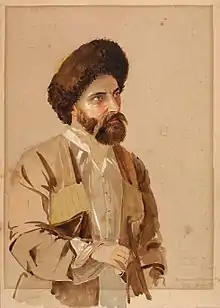

Sefer Bey Zanuqo | |

|---|---|

Sefer Bey Zanuko in 1845 | |

| Native name | Занэкъо Сэфэрбий |

| Born | ? Bığurqal, Circassia |

| Died | 1 January 1860 Shapsugh, Circassia |

| Allegiance | |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | Russo-Circassian War Muhammad Ali's seizure of power Russo-Turkish War (1828–1829) Crimean War |

| Children | Karabater Zanuqo |

Early life

Sefer Bey Zanuqo was born near Anapa, the date of his birth is unknown. He descended from the Circassian noble family of Zan. His tribal affiliation is disputed, his ancestors are variously believed to be Khegayks or Natukhajs. His father Mehmed Giray Bey, one of the richest men in Circassia, died when he was young. In 1807, the fortress of Anapa was captured by Russian troops during the course of the Russo-Circassian War and Zanuqo was given as a hostage to the Russians by the local population.[4] He was then sent to Odessa, where he was educated in the Rishelevski Lyceum.[5] His service in the Russian army ended abruptly when he fled to the mountains after a personal conflict with his regiment's commander.[6] According to British adventurer James Stanislaus Bell he soon sailed to Egypt where he lived among the Circassian Mamluks until their fall from power. Whereupon he returned to his homeland and married a Nogai princess. At the time Anapa had been conquered by the Ottoman Empire, prompting Zanuqo to travel to Constantinople where he entered into Ottoman service. He became the deputy of Anapa governor Hajji Hassan Pasha, receiving the rank of colonel. During the Russo-Turkish War (1828–1829) Anapa was recaptured by the Russians and Zanuqo was taken prisoner. He remained in Odessa until the end of the war, once he was freed he returned to Circassia, taking the role of an ambassador.[7]

Ambassador in the Ottoman Empire

The Treaty of Adrianople (1829) marked the beginning of the Russian colonization of Circassia through the establishment of military outposts and stanitsas. An assembly of Circassian tribes declared Zanuqo as their representative, dispatching him to Constantinople at the head of 200 man delegation in the spring of 1831. The Ottoman agreed to secretly supply the Circassians with weapons and ammunition, while Muhammad Ali of Egypt refused to provide any assistance. Zanuqo settled in Samsun where he continued his advocacy.[8] There he met David Urquhart, one of the first people to espouse the Circassian cause in the west and major contributor to the rise of Rusophobic attitudes in British society. In the summer of 1834, Urquhart visited Circassia where he received a petition signed by 11 chiefs requesting the British king to intervene into the conflict. Two more petitions followed in 1835 and 1836 respectively, both were reluctantly rejected by the British ambassador in Constantinople John Ponsonby, 1st Viscount Ponsonby. Lord Palmerston had previously blocked Ponsonby's initiative to include Circassia in the Eastern Question, on account of the feeble state of the Circassian resistance movement. A series of diplomatic protests by the Russian ambassador led to Zanuqo's exile to Edirne. Encouraged by Urquhart a group of British adventurers unsuccessfully attempted to run the blockade of the Circassian coast, the Mission of the Vixen created a diplomatic scandal between Britain and Russia. Encouraged by Ponsonby, Zanuqo continued to submit appeals to the British albeit to no avail. [9] In the meantime, the militant Sufi Khalidiyya movement overtook the Adyghe Habze as the leading ideology behind the Circassian resistance. Envoys sent by Imam Shamil helped coordinate the activities of the insurgents across the Caucasus and established Sharia law.[10]

Crimean War

On 4 October 1853, the Ottomans declared war on Russia launching the Crimean War. The Ottomans recruited Zanuqo and other Circassians into their army in preparation for an offensive on the Caucasus front in spring of 1854. Zanuqo was appointed as the Ottoman governor of Circassia, receiving the honorary title of pasha. On 29 October, two messengers carrying orders for Mohammed Amin Imam Shamil's naib in Circassia were dispatched from Trabzon to recruit fighters in preparation for his arrival. On 27 March 1854, Russia withdrew from its Circassian forts with the exception of Anapa and Novorossiysk as defensive measure due to the intervention of Britain and France into the conflict. In May, an Ottoman fleet carrying 300 Circassians including Zanuqo, supplies and military advisors sailed to Sukhum Kale. Zanuqo soon clashed with Mohammed Amin, when the latter refused to supply the Ottomans with recruits for fear that they will be pressed to fight outside of their homeland. In July, Amin was also elevated to pasha, exacerbating the power struggle between the two men. In March 1855, troops loyal to Zanuqo clashed with Amin's supporters on the banks of the river Sebzh. Zanuqo remained in Sukhum Kale until 10 June when he relocated to Anapa which had been recently abandoned by the Russians. In order to bridge the divide in the Circassian society created by Zanuqo's rivalry with Amin, the Ottomans placed both under the command of their countryman Mustapha Pasha.[11]

The Treaty of Paris (1856) ended the conflict, frustrating at the same time any hopes of Circassian independence. The Circassians remained politically divided and when Mohammed Amin replaced Zanuqo as the new governor, the two sides fought a second battle this time on the Sup river. An intervention of tribal elders led to compromise, when the two leaders agreed to jointly travel to Constantinople and have the sultan settle the dispute. However Zanuqo broke his oath and remained in Circassia. Zanuqo was in fact following secret Ottoman orders as he was tasked with supervising the withdrawal of the Ottoman army from the region during the course of June. He then resettled to the Shapsykhua river, destroyed the port of Tuapse to prevent Amin's supporters from using it as a supply route and called for the latter's assassination. During the second half of the year Zanuqo attempted to negotiate a peace treaty with the Russians. In January 1857, a sanguine battle between Zanuqo's and Amin's forces took place in Tuapse, Zanuqo's son Karabatir emerged victorious. Russian intelligence was well aware of the British and Ottoman involvement in the affairs of the Caucasus. In May 1857, Amin was invited to Constantinople and immediately arrested, and exiled to Damascus, a move previously planned by the imperial Majlis in an effort to improve relations with Russia. At the same time shipments of arms and ammunition to the rebels were halted. Zanuqo died in Shapsugh on 1 January 1860, oblivious to the change in Ottoman policy. He was buried in the Vordobgach valley. Karabatir succeeded him as the leader of Circassian resistance. The Russo-Circassian War officially ended on 2 June 1864, the Circassian genocide was to follow.[12]

Notes

- Заноко – искаженное Зан-уко, в котором "уко" ("сын" по-адыгски): Фелицын Е.Д. Князь Сефер-бей Зан – политический деятель и поборник независимости черкесского народа // Кубанский сборник. Екатеринодар, 1904. С. 4-5.

- Хегайки – ныне исчезнувший адыгский субэтнос, обитавший в районе крепости Анапы. Хегайки пострадали от чумы 1812 года, военных действий на Кавказе, и постепенно потеряли самобытность и растворились среди натухайцев. В XVII-XIX веках хегайки известны у иностранных авторов под разными названиями "шегаки", "схегаке", "сагаке", "хетаги", "хеаки": Челеби Э. Книга путешествий: Земли Северного Кавказа, Поволжья и Подонья // Восточная литература, ч. 1-2; Главани К. Описание Черкессии // Восточная литература; Клапрот Г.-Ю. Путешествие по Кавказу и Грузии, предпринятое в 1807-1808 годах // Восточная литература.

- Фелицын Е.Д. Князь Сефер-бей Зан – политический деятель и поборник независимости черкесского народа…, С. 6-7.

- Точная дата этого события неизвестна. Х.Х.Хапсироков в статье о Сефер-бее считает, что это произошло после 1807 г., когда мальчику было 10-12 лет (Сефер-бей Зан // Хапсироков Х.Х. Жизнь и литература. Сб. статей. М., 2002. С. 236). В этом случае дата рождения Сефер-бея должна приходиться на 1795 или 1797 год, тогда как принятой датой его рождения считается 1789 год: Хаджебиекова Ф.М. Деятельность Мухаммеда-Амина и Сефер-бей Зана как военно-политических лидеров кубанских горцев в период Кавказской войны. Автореферат дисс. к.и.н. Краснодар, 2012. С. 19. ↑

- . Дневник пребывания в Черкесии в течение 1837-1839 годов. Нальчик, 2007. Т. 2. Гл. 27., С. 173.

- Фелицын Е.Д. Князь Сефер-бей Зан – политический деятель и поборник независимости черкесского народа…, С.9-11.

- Khoon 2015, pp. 69–76.

- Khoon 2015, pp. 76–77.

- Köremezli 2004, pp. 26–36.

- Khoon 2015, pp. 77–79.

- Khoon 2015, pp. 80–88.

- Khoon 2015, pp. 88–93.

References

- Köremezli, Ibrahim (2004). "The Place of the Ottoman Empire in the Russo-Circassian War (1830-1864)". Bilkent University Thesis. Bilkent University: 1–112. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Khoon, Yahya (2015). ""Prince of Circassia": Sefer Bey Zanuko and the Circassian Struggle for Independence" (PDF). Journal of Caucasian Studies. 1 (1): 69–92. Retrieved 8 December 2017.