Selig Polyscope Company

The Selig Polyscope Company was an American motion picture company that was founded in 1896 by William Selig in Chicago. The company produced hundreds of early, widely distributed commercial moving pictures, including the first films starring Tom Mix, Harold Lloyd, Colleen Moore, and Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle. Selig Polyscope also established Southern California's first permanent movie studio, in the historic Edendale district of Los Angeles. Ending film production in 1918, the business, based on its film production animals, became an animal and prop supplier to other studios and a zoo and amusement park attraction in East Los Angeles until the Great Depression in the 1930s.[1]

| |

| Industry | Entertainment |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1896 |

| Headquarters | , United States |

| Products | Motion pictures |

| Owner | William Selig |

History

Selig had worked as a magician and minstrel show operator on the west coast of California. Later on, in Chicago he entered the film business using his own photographic equipment, free from patent restrictions imposed through companies controlled by Thomas Edison. In 1896, with help from Union Metal Works and Andrew Schustek, he shot his first film, Tramp and the Dog. He went on to successfully produce local actualities, slapstick comedies, early travelogues and industrial films (a major client was Armour and Company). In 1908 Selig Polyscope was involved in the production of The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays, a touring "multimedia" attempt to bring L. Frank Baum's Oz books to a wider public (which played to full houses but was nonetheless a financial disaster for Baum). By 1909 Selig had studios making short features in Chicago and the Edendale district of Los Angeles. The company also distributed stock film footage and titles from other studios. That year, Roscoe Arbuckle's first movie was a Selig comedy short. The company's early existence was fraught with legal turmoil over disputes with lawyers representing Thomas Edison's interests. In 1909 Selig and several other studio heads settled with Edison by creating an alliance with the inventor. Effectively a cartel, Motion Picture Patents Company dominated the industry for a few years until the Supreme Court (in 1913 and 1915) ruled the firm was an illegal monopoly. In 1910 Selig Polyscope produced a wholly new filmed version of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. The company produced the first commercial two-reel film, Damon and Pythias, successfully distributed its pictures in Great Britain and maintained an office in London for several years before World War I. Although Selig Polyscope produced a wide variety of moving pictures, the company was most widely known for its wild animal shorts, historical subjects and early westerns.

Edendale

Attracted by Southern California's mild, dry climate, varied geography for location shooting and isolation from Edison's legal representatives on the east coast, Selig set up his studio in Edendale in 1909 with director Francis Boggs, who began the facility in a rented bungalow and quickly expanded, designing the studio's front entrance after Mission San Gabriel.

An early production there was The Count of Monte Cristo. Edendale soon became Selig Polyscope's headquarters, but in 1911 Boggs was murdered by a Japanese gardener who also wounded Selig. The company produced hundreds of short features at Edendale, including many early westerns featuring Tom Mix (which were also shot at Las Vegas, New Mexico). Selig Polyscope made dozens of highly successful short movies involving wild animals in exotic settings, including a popular re-creation of an African safari hunt by Teddy Roosevelt. In 1914 Selig made 14 short experimental "talking pictures" with Scottish actor Harry Lauder.[2]

The "cliffhanger"

In 1913, through a collaborative partnership with the Chicago Tribune, Selig produced The Adventures of Kathlyn, introducing a dramatic serial plot device which came to be known as the cliffhanger. Each chapter's story was simultaneously published in the newspaper. A combination of wild animals, clever dramatic action and Kathlyn Williams' screen presence resulted in significant success. The Tribune’s circulation reportedly increased by 10% and both dance and cocktail were named after Williams, whose likeness was reportedly sold on over 50,000 postcards.

V-L-S-E, Incorporated

In 1915, Selig entered into an agreement with Vitagraph Studios, Lubin Manufacturing Company, and Essanay Studios to form a film distribution partnership known as V-L-S-E, Incorporated.[3]

Selig zoo

.jpg.webp)

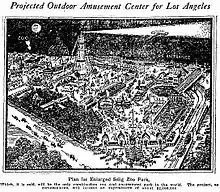

By 1913 Selig had gathered a large collection of animals for his films and spent substantial funds acquiring and developing 32 acres (130,000 m2) of land in Lincoln Heights northeast of downtown Los Angeles, where he opened a large public zoo. In 1917 Selig sold the Edendale facility to producer William Fox and moved his movie studio to the zoo in East Los Angeles. Meanwhile, World War I cut severely into the substantial revenues Selig Polyscope had been garnering in Europe and the company shunned profitable movie industry trends, which had shifted towards dramatic (and more costly) full length feature films. Selig Polyscope became insolvent and ceased operations in 1918. Mix signed with Fox back at Edendale and went on to even greater success as a matinée cowboy star. Movie studios rented animals and staged many shoots at the Selig zoo (sometimes later claiming they had been filmed in Africa). The First Tarzan movie (1918) was filmed there. In 1920 Louis B. Mayer rented his first studio space for Mayer Pictures at the site. Selig planned to develop it into a major tourist attraction, amusement park and popular resort named Selig Zoo Park with a Ferris wheel, carousels, mechanical rides, an enormous swimming pool with a sandy beach and a wave making machine, hotel, theatre, cinema, restaurants and thousands of daily visitors (more than 30 years before Disneyland). Only a single carousel was built. Selig Polyscope's extensive collection of props and furnishings were auctioned off at the zoo in 1923.

Selig finally sold the zoo following a flood during the Great Depression. Some of the animals were donated to Los Angeles County, forming a substantial addition to Griffith Park Zoo. The property was used as a jalopy racetrack during the 1940s and early 1950s. In 1955 the site was described as "an inactive amusement park."[4]

Throughout its history, names appearing on the zoo gate included:

- Selig Zoo and Studio

- Selig Zoo

- Selig Jungle Zoo

- Luna Park Zoo

- California Zoological Gardens

- Zoopark

- Lincoln Amusement Park

The carousel survived on the site until 1976 when it was destroyed by fire. The former Selig zoo's arched front gate with its lavish animal sculptures was a crumbling landmark in Lincoln Heights for many decades. By 2003 the sculptures were reportedly being restored for installation at the Los Angeles Zoo and in 2007 tennis courts were on the site.[5]

Legacy

Academy library

In the late 1940s, Selig made a large donation of business records to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Library. The William Selig papers, together with the donation, include Selig's correspondence, scripts, scrapbooks, production files and six feet of photographs that include production stills from over 500 films that are otherwise lost (only about 225 of the over 3,500 films released by Selig between 1896 and 1938 have survived into the present day). This collection still requires further study.[6]

Lost films

The potential of movies as long term sources of revenue was unknown to early movie industry executives. Films were made quickly, sent into distribution channels and mostly forgotten soon after their first runs. Surviving prints were typically stored haphazardly, if at all. Nitrate film stock, in common use until the mid-20th Century, was chemically volatile and many prints were lost in fires or decomposed in storage. Some were recycled for their silver content or simply thrown away to save space. Out of Selig Polyscope's hundreds of films, only a few copies and scattered photographic elements are known to survive.

Partial filmography

.jpg.webp)

- The Tramp and the Dog (1896)

- Soldiers at Play (1898)

- Something Good – Negro Kiss (1898)

- Chicago Police Parade (1901)

- Dewey Parade (1901)

- Gans-McGovern Fight (1901)

- Fun at the Glenwood Springs Pool (1902)

- A Hot Time on a Bathing Beach (1903)

- Business Rivalry (1903)

- Chicago Fire Run (1903)

- Chicago Firecats on Parade (1903)

- The Girl in Blue (1903)

- Trip Around The Union Loop (1903)

- View of State Street (1903)

- Tracked by Bloodhounds; or, A Lynching at Cripple Creek (1904) (survives)

- Humpty Dumptry (1904)

- The Tramp Dog (1904)

- The Hold-Up of the Leadville Stage (1904)

- The Grafter (1907)

- The Count of Monte Cristo (1908)

- Damon and Pythias (1908)

- The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays (1908)

- Briton and Boer (1909)

- Hunting Big Game in Africa (1909)

- The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1910) (survives)

- The Sergeant (1910) (survives)

- The Way of the Eskimo (1911)

- Lost in the Arctic (1911)

- Life on the Border (1911) (partial section survives)

- The Coming of Columbus (1911)

- Brotherhood of Man (1912)

- Kings of the Forest (1912)

- War Time Romance (1912)

- The Adventures of Kathlyn (1913)

- Arabia, the Equine Detective (1913)

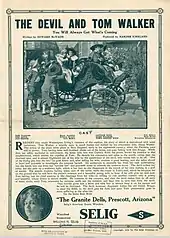

- The Devil and Tom Walker (1913)

- The Sheriff of Yavapai County (1913)

- Wamba A Child of the Jungle (1913)

- The Spoilers (1914) (survives)

- A Black Sheep (1915)

- House of a Thousand Candles (1915)

- The Man from Texas (1915)

- The Crisis (1916)

- The Garden of Allah (1916)

- The City of Purple Dreams (1918)

- Little Orphant Annie (1918)

References

- "Lincolnheightsla.com". lincolnheightsla.com. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- "Silent Era : Progressive Silent Film List". www.silentera.com. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- Wagenknecht, Edward (13 October 2014). The Movies in the Age of Innocence, 3d ed. McFarland. ISBN 9780786494620. Retrieved 9 September 2018 – via Google Books.

- "Los Angeles Times: Lionesses on archway of entrance to the Selig Zoo". UCLA Digital Library. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Hall, Carla (May 14, 2009). "Zoo to display lion statues from early L.A. menagerie". LA Times. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Erish, Andrew A. (2012). Col. William N. Selig: The Man Who Invented Hollywood. University of Texas Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0292728707. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Selig Polyscope Company. |

- Lincoln Heights page with pictures of recovered statues

- The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (one of Selig Polyscope Company's few surviving films) download at Internet Archive