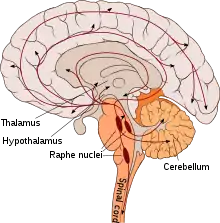

Serotonin pathway

A serotonin pathway identifies aggregate projections from neurons which synthesize and communicate the monoamine neurotransmitter serotonin. These pathways are relevant to different psychiatric and neurological disorders.[1][2][3]

Pathways

| Pathway Group | Origin[4] | Projections | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rostral Group | Caudal linear nucleus (cell group B8) |

Shares overlap with the dorsal raphe nuclei | |

| Dorsal raphe nucleus (cell groups B6, B7) |

|

The anterior dorsal raphe primarily projects to the cortex, neostriatum, amygdala and SN, while the caudal division of the dorsal raphe projects to the latter three. The highest density of cortical innervation is in layer 1. | |

| Median raphe nucleus (cell groups B5, B8) |

Projections into the hippocampus are the most dense in the subiculum, followed by Ammon's horn and the Dentate gyrus. Projections into the VTA modulate firing rate, increasing the rate with lower activity, and depressing it with higher activity. | ||

| Caudal Group | Nucleus raphe magnus (cell group B3) |

||

| Nucleus raphe obscurus (cell group B2) |

|

All three of the trigeminal motor nuclei receive dense innervations. | |

| Nucleus raphe pallidus (cell group B1) |

|

Some of the serotonergic spinal cord axons may originate in the spinal cord itself. | |

| Lateral medullary reticular formation |

Function

Given the wide area that the many serotonergic neurons innervate, these pathways are implicated in many functions, as listed above. The caudal serotonergic nuclei heavily innervate the spinal cord, medulla and cerebellum. In general, manipulation of the caudal nuclei(e.g. pharmacological, lesion, receptor knockout) that results in decreased activity decreases movement, while manipulations to increase activity cause an increase in motor activity. Serotonin is also implicated in sensory processing, as sensory stimulation causes an increase in extracellular serotonin in the neocortex. Serotonin pathways are thought to modulate eating, both the amount as well as the motor processes associated with eating. The serotonergic projections into the hypothalamus are thought to be particularly relevant, and an increase in serotonergic signaling is thought to generally decrease food consumption (evidenced by fenfluramine, however, receptor subtypes might make this more nuanced). Serotonin pathways projecting into the limbic forebrain are also involved in emotional processing, with decreased serotonergic activity resulting in decreased cognition and an emotional bias towards negative stimuli.[5] The function of serotonin in mood is more nuanced, with some evidence pointing towards increased levels leading to depression, fatigue and sickness behavior; and other evidence arguing the opposite.[6]

See also

References

- Juhl, J. H. (1 October 1998). "Fibromyalgia and the serotonin pathway". Alternative Medicine Review: A Journal of Clinical Therapeutic. 3 (5): 367–375. ISSN 1089-5159. PMID 9802912.

- Dayer, Alexandre (15 January 2017). "Serotonin-related pathways and developmental plasticity: relevance for psychiatric disorders". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 16 (1): 29–41. ISSN 1294-8322. PMC 3984889. PMID 24733969.

- Helton, Sarah G.; Lohoff, Falk W. (1 January 2015). "Serotonin pathway polymorphisms and the treatment of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders". Pharmacogenomics. 16 (5): 541–553. doi:10.2217/pgs.15.15. ISSN 1744-8042. PMID 25916524.

- Hornung JP (2009). "The Neuroanatomy of the Serotonergic System". In Jacobs B, Müller CP (eds.). Handbook of the Behavioral Neurobiology of Serotonin (1st ed.). London: Academic Press. pp. 51–55. ISBN 9780123746344.

- Jacobs, edited by Christian P. Müller, Barry (2009). Handbook of the behavioral neurobiology of serotonin (1st ed.). London: Academic. pp. 309–367. ISBN 9780123746344.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Andrews, Paul W.; Bharwani, Aadil; Lee, Kyuwon R.; Fox, Molly; Thomson Jr., J. Anderson (1 April 2015). "Is serotonin an upper or a downer? The evolution of the serotonergic system and its role in depression and the antidepressant response". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 51: 164–188. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.01.018. PMID 25625874. S2CID 23980182.