Shimenawa

Shimenawa (標縄/注連縄/七五三縄, lit., 'enclosing rope') are lengths of laid rice straw or hemp[1] rope used for ritual purification in the Shinto religion.

| Shimenawa | |

|---|---|

| しめ縄 | |

| |

| Material | Hemp fiber/Straw |

| Present location | Japan |

| Culture | Shinto |

Shimenawa vary in diameter from a few centimetres to several metres, and are often seen festooned with shide—traditional paper streamers. A space bound by shimenawa typically indicates a sacred or ritually pure space, such as that of a Shinto shrine.[2] Shimenawa are believed to act as a ward against evil spirits, and are often set up at a ground-breaking ceremony before construction begins on a new building. They are often found at Shinto shrines, torii gates, and sacred landmarks.

Shimenawa are also placed on yorishiro, objects considered to attract spirits or be inhabited by them. These notably include being placed on certain trees, the spirits considered to inhabit them being known as kodama; cutting down these trees is thought to bring misfortune. In the case of stones considered to inhabit spirits, the stones are known as iwakura (磐座/岩座).[3]

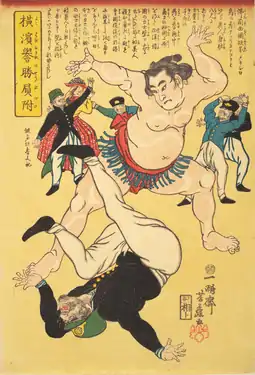

A variation of the shimenawa are worn in sumo wrestling by yokozuna (grand champions), during the entrance ceremony to debut as grand champion rank. In this instance, shimenawa are used as yokozuna are seen as being living yorishiro (a vessel capable of housing a spirit, known as shintai when inhabited by a spirit), and are therefore visually distinguished as "sacred".

Shimenawa and Shinto

The Shinto mythology firstly introduces the existence of shimenawa. It is a hallowed sacrifice related to the Japanese god called Kami, used in various Shinto ceremonies. Aboriginal people in Japan respect and admire shimenawa since ancient times.

Mythical origin of shimenawa

The prototype of shimenawa in Shinto is a rope of Amaterasu, Japan’s “Heaven-shining great kami”.[4] According to “A popular dictionary of Shinto”, Amaterasu hid in a cave called Amano-Iwato as she was in an argument with her brother Susanoo.[4] Therefore, the entire universe had lost lusters.[5] Other deities tried plenty of ways to attract Amaterasu to come out of the cave.[5] At the moment that Amaterasu left the cave, kami Futo-tama used a magical rope that drew a line of demarcation between her and the cave to avoid her back to the cave again.[4] That rope was shimenawa. Because of shimenawa, the universe resumed lighting.[5]

Shimenawa and Shinto shrine

Shimenawa and nature delimited the Shinto Shrines in early times. The Shrine in Shinto is the place for kami.[6] Local people held rituals in shrines. Early shrines were not composed of classical buildings.[6] Rocks, plants and shimenawa delimited this area.[6] This related to Japanese respect for nature. In Shintoism, all the sacred objects and nature were personified.[6] Even a sword from a deceased Japanese warrior could be seen as the god because of its internal spirit and sense of awe.[7] In modern-day society, there are still some sites that use shimenawa to demarcate such as Nachi Waterfalls in Kumano.[6] A rock in Ise Bay was still connected by shimenawa as well.[6]

Different kinds of shimenawa

Shimenawa usually in a shape similar to a twisted narrow rope with various decorations on it.[4] Zig-zag paper and colorful streamers called shide are the common partners in the decoration of shimenawa.[4] The size of shimenawa differs from simple to complicated. In shrines, it usually appears tapered and thick with a diameter of 6 feet.[4]

Decorations on shimenawa

Shimenawa appears with different kinds of decorations on it. Each ornament has its blessings and meanings.

- Daidai: a kind of bitter orange which is a decoration on shinmenawa. This combination could bring good fortune and prosperity for people.[8]

- Gohei or Shide: folded white paper which stands for lightning, a symbol of fertility.[9]

- Pine twigs: pine twigs with shimenawa has a meaning of healthy growth of next generation as well as longevity of the elderly.[8]

Biggest shimenawa in Japan

The biggest shimenawa is located at Izumo Taisha Grand Shrine,[8] which occupies over 27,000 square meters of land in Japan. The shimenawa is 13.5 m in length and 8 m in width and was made by more than 800 indigenous people in Japan.[8]

Use of shimenawa

Shimenawa in Mountain Opening Ceremony

Shimenawa is used in Japan’s Mountain Opening Ceremony which held every May 1.[5] There are over 100 Shinto believers who participate in this ceremony.[5] It is a 2-hour journey that they climb from Akakura Mountain Shrine to Fudō Waterfall.[5] The overall purpose is to carry the rope called shimenawa and fix it between two towering trees securely.[5] When the ceremony is finished, people will get together and drink a lot.[5]

Shimenawa in New Year's Celebration

In Japan’s new year celebration, ornaments such as shimenawa decorate every household. During this time period, local residents usually hang it on the door in order to drive away evils.

Shimenawa and Hadaka Matsuri

Hadaka Matsuri, Japan's Naked Festivals.[4] This festival is held during the New Year period for more than 500 years of history.[4] According to a book called “Immortal wishes”, the young generation naked their upper body as well as wear clothing called mawashi in cold weather in order to show their strength and manliness.[4] It also includes various activities such as ‘jostling, climbing fighting with a wooden ball’ as well as being sprayed with water.[4] Sometimes these festivals will hold in Shinto Shrines.[4] Those people in mawashi will put shimenawa on the roof to wish them good luck for the upcoming year.[4] Shimenawa will be served for kami as a sacrifice in the shrine on New Year’s day.[4]

Based on the recent news in The Week, the 2020's Hadaka Matsuri Festival is held in February at Saidaiji Kannonin Temple which takes the distance of thirty minutes away from Okayama City.[10] Approximately 10,000 men participate in the activity, competing for a priest's branch which thrown into these groups of men from a window which is 12 feet above them.[10] All the men try their best to get as close as to the branch in thirty minutes for the purpose of wishing them a lucky year.[10]

Shimenawa in sumo

Sumo is Japan’s traditional national sport.[4] It still involves some elements of Shintoism.[4] Sumo is held in Shinto Shrines.[4] The whole arena is composed of shimenawa.[4] Moreover, the champion of the sumo has to wear shimenawa around his waist in order to attend a victorious ceremony called dohyo-iri.[11]

How to make a shimenawa

Material and Preparation process

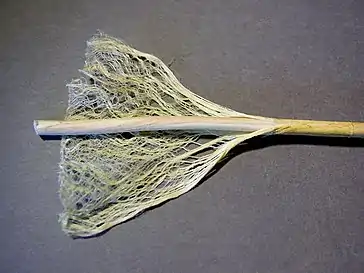

Hemp fiber with a historical origin from prehistoric times is the basic material of making a shimenawa.[11] Japanese use hemp to make clothes and paper even eat the seeds of hemp to make grease since the Edo period.[11] In Shintoism, people regarded hemp as a sacred food with a meaning of purity and fertility.[11] It also could be used in rituals and making shimenawa.[11] After Cannabis Control Act published in 1948, people are not allowed to plant hemp seeds.[11] They begin to use straw instead as the raw material of shimenawa.[12] In order to make practical and effective use of straws, people use stems to make shimenawa.[12] During the process of production, the stems have to be cut between 70 to 80 days to keep the stems maintain its nutrition because the plants will give all the fibers to the grains.[12] Farmers could get benefits if they have shorter period to get harvest as it could raise the overall production.[12] Although the time is shorter, the selling price of the shimenawa in the color of green is same of the rice which is mature.[12] After the shimenawa straw is collected by the machineries, it will be heated for more than 10 hours in the factory.[12] According to the worker in the factory, the theory behind this is to avoid the stems being dried by the sun.[12] The last step is to select the good stem which did by hand in order to create shimenawa which could vary in sizes.[12]

Objects related to shimenawa

Heihaku

Heihaku (also called mitegura or heimotsu), a vertical shape wooden stick with zigzag stripes paper, cloth or mental called gohei on it usually in white or red which owned by priests.[4] People put heihaku in front of honden doors or they could take it by themselves.[4] In a procession called shinkō-shiki, heihaku is seen as a sacrifice for the god or a symbol of existence of god.[4] In the ancient times, people offers cloth to the Shinto shrines which is quite similar to today’s procession.[4] Heihaku sometimes is also used in the way which shide did.[4] The stripes can also hang on the shimenawa.[4]

Himorogi

The basis form of Shinto shrine, including the pure space which delimited by shimenawa is himorogi.[4] Sometimes there is a sakura tree surrounded by green plants appears in this area, symbolizing God’s position or seat.[4]

Kazari

Like shimenawa, kazari is also a New year’s decoration in Japan.[4] It is full of distinct colors.[4] Objects which is related to rice like rice-cake and rice-straw often appear with kazari.[4] The purpose of that is to bring good fortune to people.[4]

Kamidana

Kamidana is a reduced version of shimenawa which is used in daily life.[4] It takes control of rice, salt, and water which could bring people good luck.[4] Therefore, it always appears in the business area such as restaurants as well as conventional industries.[4] Places like the police stations and board ships will also familiar with kamidana.[4]

Raijin

Raijin is a kami that controls thunder, solving the problem of drought for human-beings.[4] According to A popular dictionary of Shinto, there is a custom in Japan which talks about shimenawa and Raijin.[4] Local residents in Japan’s Kantō area will put a shimenawa between the green bamboos after a bolt of lightning appears on the planted rice field.[4] That action illustrates people’s gratitude to the Raijin.[4]

Shinboku

Holy tree which located in Shinto shrine that could be indicated by shimenawa.[4] It also be seen as god’s shintai.[4] These trees surrounding the shrine are seen as the part of Shinto shrine.[4]

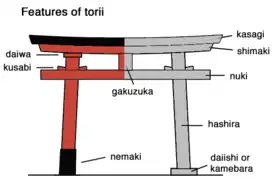

Torii

Torii is an archway which composed of two round posts and an upper cross-beamrope in two layers.[4] The ends of the cross-beamrope typically has curve shape which is a symbol of a style called myōjin.[4] There is a under-cross-beam just below the top individually.[4]

Torii first appears in Japan at the time Chinese culture and Buddhism are introduced.[4] In today's society, there is no evidence to show the origination of torii's shape and name.[4] Local researchers predict the name of torii comes from Sanskrit.[4]

With the exception of the cross-beamrope, local residents also use shimenawa to decorate the archway.[4] It could also be seen as a kind of torii called shimenawa torii which consists of only two posts and a shimenawa, using for a temporary torii instead of a permanent one.[4]

In Japan, there are more than 20 different kinds of torii various from simple wooden to concrete portals which popular in Shinto shrines.[4] The style of torii is not strictly based on the style of shrines as there could be different styles of torii in one shrine.[4]

Similar to shimenawa, torii also has meaning in Shintoism. It represents a place that could open to the world, people, or any relationships in Shinto.[7] When people lost their ways, it could save them and help them back to the right trajectory of their lives.[7] The purpose of torii and shimenawa is the same for bringing the lost people to the kami-filled world.[7]

Shimenawa in arts

During the 2017 Yokohama Triennale, Indonesian artist Joko Avianto’s work of art called The border between good and evil is terribly frizzy is displayed in the center of the hall in Yokohama Museum.[13] The name comes from the quote “The border between good and evil is terribly fuzzy” of Czech novelist Milan Kundera.[13] Avianto changes the final word to “frizzy” because of the twisted shape of his artwork.[13] The overall shape is inspired by shimenawa. Shimenawa often hangs across the torii which is the gate of the Shinto shrine.[13] In Shintoism, shimenawa has a meaning of a tool which separate ‘the sacred and the profane’, or ‘the ideal and the secular’.[13] Avianto also has his own understanding of shimenawa.[13] He believes that shimenawa is similar to the clouds which surround the Mount Sameru, symbolizing the boundary between ‘the earth and heaven’.[13] Therefore, Avianto follows his original intention which is to set a gate which similar to shimenawa above the visitors, attracting them to enter the border.[13] As the visitors move around just like they are traveling to the two opposite world which reflects the meaning of the artwork’s name.[13] The architecture is made of more than 1,600 pieces of weaved shoots Indonesian bamboo.[13] There is a group of artists bring those bamboos to that museum, building this sculpture layer by layer from the foundation.[13] The reason why Avianto choose to use bamboo instead of high-level stones as the sculpture material because he wants to integrate daily life and art.[13]

Taiwan and Japan transactions of shimenawa

Taiwan’s Miaoli County began to produce shimenawa and exported it to the markets in Japan since 1998.[12] In that era, Japanese manufacturers visited this place and found the high quality of straw as well as the relatively low cost of producing straws.[12] However, there are no local residents who know the way to make a shimenawa.[12] Therefore, the Japanese started to provide free classes for them to study the skills for producing shimenawa.[12] Since then, the shimenawa industry developed rapidly.[12] The craftsmen in Taiwan harvest straws to make shimenawa while Japanese manufacturers provide samples or finished products to the customers according to their orders.[12] This mutually beneficial relationship benefits both Japanese and residents in Miaoli County as the Japanese found cheap sources of shimenawa and reduce the basic cost of production and help the local residents to find a job for a living.[12]

Based on Taiwan Today’s interview of the local residents, the 1990s was a period of industrial disruption.[12] Many large shimenawa factories appeared at that time but the good times didn’t last long.[12] Most factories were forced to shut down in a few years later and only one factory left to continue developing in Miaoli County.[12] Other remaining factories chose to hand over the work to Southeast Asian, especially for Vietnam for a lower cost production.[12] After Vietnamese workers finished the orders from Japan, they need to ship back the shimenawa in batches and put a tag called “Made In Taiwan” on each shimenawa.[12]

Later in 2005, a large number of shimenawa orders were transferred back to Taiwan because buyers in Japan found that the quality of shimenawa produced in Vietnam was poor compared to Taiwan.[12] The Japanese are unwilling to allow other countries to control the quality of shimenawa.[12] This shows the full trust of Japanese buyers to the Taiwan's craftsmanship.[12]

Image gallery

See also

![]() Media related to Shimenawa at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Shimenawa at Wikimedia Commons

- Kamidana, household Shinto shrines

- Kanjo Nawa – a custom utilizing shimenawa

- Kumihimo, traditional Japanese braided cord

- Saekki

References

- https://www.japantoday.com/smartphone/view/national/mie-govt-rejects-cannabis-cultivation-request-for-shinto-rituals

- Cf. Kasulis (2004:17-23).

- "Shimenawa & Rock", More glimpses of unfamiliar Japan, Thursday, March 18, 2010

- Bocking, Brian (1995). A Popular Dictionary of Shinto. Richmond, Surrey, U.K.: Curzon Press.

- Swanson, Paul L (2004-05-01). "Review of: Ellen Schattschneider, Immortal Wishes: Labor and Transcendence on a Japanese Sacred Mountain". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. doi:10.18874/jjrs.31.1.2004.232-233. ISSN 0304-1042.

- Evans, Marcus (2014-05-01). "Shinto: An Experience of Being at Home in the World With Nature and With Others". Masters Theses & Specialist Projects.

- Kasulis, Thomas P. (2004-08-31). Shinto. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-6430-9.

- Forlano, Laura; Steenson, Molly Wright; Ananny, Mike, eds. (2019). Bauhaus Futures. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-35492-9.

- Jiao, Yupeng (2020-11-17). "Rural Wandering Martial Arts Networks and Invulnerability Rituals in Modern China". Martial Arts Studies. 0 (10): 40. doi:10.18573/mas.109. ISSN 2057-5696.

- "Hadaka Matsuri: inside Japan's naked festival". The Week UK. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- Price, Stephanie (2020-09-11). "Cannabis, hemp, CBD: the Japanese cannabis landscape". Health Europa. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- China (Taiwan), Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of (2009-02-01). "Hanging in There". Taiwan Today. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- "Joko Avianto at the Yokohama Triennale 2017. Nafas Art Magazine". universes.art. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

Further reading

- Kasulis, Thomas P. (2004). Shinto: The Way Home. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2794-5.