Sicilian Renaissance

The Sicilian Renaissance forms part of the wider currents of scholarly and artistic development known as the Renaissance in Italy and Europe as a whole. Spreading from that movement's main centres in Florence, Rome and Naples, when Renaissance Classicism reached the island of Sicily it fused with influences from local late medieval and International Gothic art and Flemish painting to form a distinctive hybrid. The 1460s is usually identified as the start of the development of this distinctive hybrid Renaissance on the island, marked by the presence of Antonello da Messina, Francesco Laurana and Domenico Gagini, all three of whom influenced each other, sometimes basing their studios in the same city at the same time.

The Flemish influence was particularly strong in Messina due to its trade links with the Hanseatic League and the resulting influx of Flemish artists to Sicily in both the Renaissance and Baroque eras.[1] In the 15th and 16th centuries the Kingdom of Sicily was initially part of the dynastic confederation headed by the Crown of Aragon and later became part of the Spanish Empire under Charles V and his successors, further linking it to artistic developments in the Low Countries, Germany and Spain.

Lost works

15th century

Early 15th century Sicilian art shows marked Franco-Provençal and Pisan-Sienese influences, peaking in the The Triumph of Death fresco now in the Palazzo Abatellis. Major artists of that period included Gaspare da Pesaro and his son Guglielmo Pesaro. Intense architectural activity maintained a late-Gothic form with strong influences from Iberia and especially Val di Noto and with shapes and decorative elements surviving from Norman Sicilian architecture.

That period saw the economy and population of the island's two main cities, Palermo and Messina, both grow thanks to their ports and large communities of Venetian, Pisan, Lombard and Genoese merchants. The cities' social structures were also modernised with the addition of a class of civil servants and businessmen who imitated noble families by building palaces and family chapels and commissioning expensive art. Along with the arrival of several artists from mainland Italy and the influence of the art-scene in Naples under Alfonso II, this combination of factors led to major changes in Sicily's artistic expression. By the end of the century, several lasting characteristics of Sicilian Renaissance culture had formed - clergy's preeminent role as commissioners, several artists from (and often artistically trained within) religious orders, the differences between Messina and Palermo and between Catania and Siracusa and local artists' journeys to mainland Italy to study.

Antonello and painting

Sicily's early Renaissance was dominated by Antonello da Messina, who trained in Naples, Venice, possibly Milan and indirectly in Flanders, showing the circulation of ideas which marked this era. His commissions from Sicily and his decision to return there in 1476 after his time in Venice made him the island's first Renaissance artist, as did his busy studio, later continued by his family, which fused local traditions with a new taste for the human form, portraiture and the artist as valued genius rather than simply an anonymous artisan.

Neither his family members (his son Iacobello and his nephews Antonio di Saliba, Pietro di Saliba and Salvo d'Antonio) nor any of his direct and indirect pupils and followers (Alessandro Padovano, Giovanni Maria Trevisano, Giovannello da Itala, Marco Costanzo, Antonino Giuffré, Alfonso Franco, Francesco Pagano, some of whom were also active in Venice[2] became major artists in their own right. However, their own works and their studio copies of Antonello's works spread throughout Sicily and Calabria, where several works by Antonello's school survive, although attribution can be difficult since main painters in his circle have been little-studied. The most evolved of them was Salvo d'Antonio, who added his own style and both Venetian and Ferrarese influences.

Painting developed less dramatically in Palermo in that period. Its two main artists were Tommaso De Vigilia, still clinging to Catalan motifs, and Riccardo Quartararo, trained in Naples and a major influence on several minor local artists.

Christ at the Column, follower of Antonello da Messina

Christ at the Column, follower of Antonello da Messina Madonna and Child, by Antonio di Saliba

Madonna and Child, by Antonio di Saliba Madonna and Child with Saints by Salvo d'Antonio

Madonna and Child with Saints by Salvo d'Antonio

Sculpture in Palermo

Renaissance sculpture also reached Sicily through the work of Francesco Laurana, who was active there for a number of years after 1466. He opened a studio in Palermo which proved influential on several artists such as Domenico Pellegrino, Pietro de Bonitate and Iacopo de Benedetto and began to spread the early Renaissance style across the island. The best example of this crucial moment for Sicilian art is San Francesco d'Assisi in Palermo, particularly its fully Renaissance Mastrantonio chapel (designed and sculpted by Laurana and Pietro da Bonitate) and Antonello Speciale's tomb monument (attributed by some to Laurana but more probably sculpted by Domenico Gagini). Gagini and Laurana both came from Naples, where they had worked on the triumphal arch at the Castel Nuovo - the studio working on that arch produced several important artists and was key to the course of Renaissance art in southern Italy.

Filarete's Trattato states that Gagini studied under Filippo Brunelleschi. In 1463 he moved to Sicily, staying there until his death and founding a studio and a dynasty of sculptors which played a long and major part in Sicilian sculpture. He brought to the island the many cultural influences which had marked his training, including the use of Carrara marble. His first works on Sicily were linked to San Francesco, a key site for the Renaissance's introduction onto the island - Laurana was also active there, whilst Gagini produced the St George and the Dragon altarpiece for the church.

Other marble sculptors from Tuscany and Lombardy also opened studios on Sicily, mainly in Palermo and Messina - these included the Lombard Gabriele di Battista who had worked in Naples like Gagini.[3] Palermo's marble sculptors, mainly from Carrara, even formed a corporation or guild in 1487. They produced altarpieces, doorways, window-frames and columns which bit by bit added decorative language to native Sicilian architecture according to their commissioners' more and more pressing requests, melding Late Gothic architecture with Renaissance architectural sculpture.[4]

Sculpture in Messina

_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall'Orto%252C_4-July-2008.jpg.webp)

The most notable artists of this period active in Messina were Giorgio da Milano, Andrea Mancino, Bernardino Nobile and especially Giovan Battista Mazzolo from Carrara, head of an important studio which included Messina-born Antonio Freri. Domenico Gagini's son Antonello was also in Messina between 1498 and 1507.[5]

As in Palermo, Toscano and Lombard artists brought the classicising sculptural elements to the city and its surrounding areas as well as Calabria. Earlier historians have argued that these elements were imposed on Messina before the end of the 15th century, before they reached the rest of Sicily,[6] but the consensus is now that sculpture in Messina remained in its Late Gothic mode throughout the 15th century, despite the presence of some Renaissance decorative elements, although many examples from this period have been destroyed by earthquakes, making a full investigation of it difficult.[5] This dialogue between architecture and sculpture can be seen in the late 15th century Renaissance doorways of the church of Santa Lucia del Mela, attributed to Gabriele di Battista, and the 1494 side door to the church of Mistretta, attributed to Giorgio da Milano.[5]

Architecture

Renaissance influence did not spread through all Sicilian architecture straight away. The main 15th century Sicilian architect, Matteo Carnilivari, used a personal style still marked by Gothic and Catalan influences, such as his design for Santa Maria della Catena. His prestige as an architect blocked most Renaissance influence on Sicilian architecture during that century besides decorative sculptural elements. Other than the few surviving works by Laurana from this period, only minor examples of Renaissance architectural style from the late 15th century can be found on Sicily, such as the Ventimiglia chapel in San Francesco church in Castelbuono.

Early 16th century

Architecture

_vincitore_di_lepanto%252C_02.JPG.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Little by little Renaissance classical elements were absorbed into Sicilian architecture, mainly coalescing episodically as in Syracuse Cathedral's sacristy or in small buildings such as the chapels added to churches.[7] Those chapels included the Naselli chapel at San Francesco in Comiso, the Confrati chapel at Santa Maria di Betlem in Modica, the 'Dormito Virginis' chapel at Santa Maria delle Scale in Ragusa, the Marinai chapel at Annunziata church in Trapani (designed by Gabriele di Battista[8]).

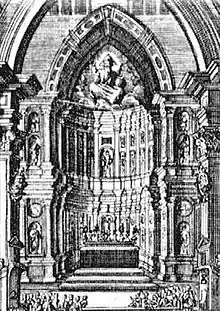

The Renaissance style was also used for a new facade of Syracuse Cathedral (destroyed in the 1693 earthquake) and Antonello Gagini's grandiose marble 'tribuna' in Palermo Cathedral (destroyed at the end of the 18th century).[9] The latter was probably the most significant piece of Sicilian Renaissance sculpture and architecture, built between 1510 and 1574 and completed after Antonello's 1537 death by his sons Antonino, Giacomo and Vincenzo. Santa Maria di Porto Salvo was probably also designed by Antonello, combining local pointed arches with a fully Renaissance use of space.

Painting

In 1517 Raphael's Christ Falling on the Way to Calvary arrived in Palermo, where it influenced several painters and sculptors. Two years later Vincenzo da Pavia became active in the same city. Both events introduced the modern "manner" into the city, although its overall atmosphere still remained wedded to that of the previous century.

Several artists arrived in Sicily from Naples early in the century, such as Mario da Laurito, whilst during the same era many Sicilian artists were active elsewhere, such as Giacomo Santoro in Rome and Spoleto and Tommaso Laureti in Rome and Bologna. Other Mannerist painters from mainland Italy such as Orazio Alfani were active in Palermo. Another Sicilian artist was Vincenzo degli Azani from the first half of the century.

Between 1500 and 1520 Cesare da Sesto spent two stays in Messina, bringing a style halfway between Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci which influenced the city's native artists, especially Girolamo Alibrandi, well known in his own era but few of whose works survive and about whom few documents remain.

Two years after the 1527 Sack of Rome, Polidoro da Caravaggio settled in Messina, remaining there until his death. He brought Raphael's figurative style from Rome to Sicily, though his own style was also influenced by Sicilian religiosity, with more and more pathos-inducing figures. Polidoro collaborated on the temporary installations for Charles V's entry into Messina in 1535, an important moment for the island's art. Polidoro's most important pupil was Deodato Guinaccia, long active in Messina. A large group of Sicilian Mannerist painters such as Stefano Giordano also worked in Naples, just as Mannerists from Naples were also active on Sicily.

Sculpture

16th century sculpture on Sicily played a key role in the island's decisive move from the International Gothic to Renaissance style. This evolution occurred differently in Messina compared to the rest of the island. In Palermo, for example, the Gagini workshop was active throughout the century and beyond, alternating between repetitive studio works and prestigious commissions which also included typically Sicilian forms such as marble tabernacles flanked by angels. Its most important artist was Antonello Gagini, son of Domenico, 'console' of Palermo's marble-workers. Antonello's artistic training was a complex one, taking him to Rome where he worked alongside Michelangelo, and he also worked in Messina. That up-to-date training allowed him to override the stylistic features he had learned from Laurana and his own father Domenico, which by then had become fashionable.[10] As well as members of the Gagini family, that studio also included Giuliano Mancino, Antonio and Bartolomeo Berrettaro, Vincenzo Carrara and Fedele Da Corona.

By contrast, an influx of several important Tuscan sculptors to Messina long dominated the city's sculpture, spreading Mannerism not only throughout Sicily but also to Calabria.[11] After a long period of wandering, Michelangelo's pupil Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli settled in Messina from 1547 to 1557, producing the city's Fontana del Nettuno and Fontana di Orione and leaving behind several followers such as Giuseppe Bottone on his departure. Martino Montanini also arrived in Messina in 1547, staying until 1561 and becoming Montorsoli's collaborator and successor as architect to the city's cathedral, sculpting several now-lost sculptures for it.[12] Bartolomeo Ammannati's pupil Andrea Calamech also settled in the city in 1563, heading an important studio which included his son Francesco, his nephew Lorenzo Calamech and his son-in-law Rinaldo Bonanno.

Michelangelo Naccherino and Camillo Camilliani were two other Mannerist sculptors present on Sicily at this era. Alongside marble sculpture, the island's traditional stucco and woodcarving styles continued, leading to most surprising results in the 17th century.

Later 16th century

However much or little Sicily adhered to Renaissance forms, however more or less late compared to the rest of Italy and however more or less conditioned by pre-existing Sicilian artistic traditions, in the second half of the 16th century Sicily fully caught up with artistic developments in the rest of Italy and Rome in particular, taking on the complex mix of late Mannerism, classicism and Counter Reformation themes among others.

Artists and architects from the main cultural centres in the rest of Italy continued to emigrate to Sicily in this era, bringing new developments to Sicily. That trend ended after this period and the main artists active in Sicily in the 17th century were Sicilians, often trained in Rome, a trend which had already begun in the second half of the 16th century.

Mannerist architecture

City councils on Sicily not only used Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli and particularly Andrea Calamech as sculptors but also as architects,[13] introducing Mannerist classicist to Messina with now-lost works such as the Palazzo Reale and Calamech's Ospedale Maggiore.

One further Sicilian interpreters of Mannerist architecture was Natale Masuccio (designer of buildings such as Messina's Monte di Pietà, whose typical rusticated-order doorway survives). Another was Michelangelo's pupil Jacopo Del Duca, initially active in Rome where he completed some of his master's projects, before returning to his native Sicily in 1588. There he was active for ten years in Messina, where he succeeded Calamech as city architect and designed several buildings, almost all now destroyed by earthquakes but important for subsequent developments in Sicilian architecture.[14]

Move towards the Baroque

Sicilian painting in the second half of the 16th century was updated to all the various trends of the Italian figurative art but did not produce any major painters. Its most important proponents were Antonio Catalano, Giuseppe Spatafora, Antonio Ferraro and Giuseppe d'Alvino.

During those fifty years artists of several different styles arrived in Sicily, including the Spaniard Juan de Matta (also active in the first half of the century), the Flemish painter Simone de Wobreck (active on Sicily from 1557 to 1587),[15] and Orazio Borgianni from Rome (active in Sicily in the 1590s before moving to Spain).

References

- Cornelius Walford, An Outline History of the Hanseatic League, More Particularly in Its Bearings upon English Commerce (PDF), p. 98.

- (in Italian) Francesco Abbate, Storia dell'arte nell'Italia meridionale, Volume 3, Donzelli Editore, 2001, pag.21, ISBN 88-6036-413-2

- (in Italian) Boscarino, S., L'architettura dei marmorari immigrati in Sicilia tra il Quattrocento e il Cinquecento, in Storia Architettura, 1-2, 1986, pp. 11-40

- (in Italian) Fulvia Scaduto, Fra Tardogotico e Rinascimento: Messina tra Sicilia e il continente, in "Artigrama", n. 23, 2008, pagg.301-326

- (in Italian) Fulvia Scaduto, op. cit., 2008

- (in Italian) Maria Accascina, Indagini sul primo Rinascimento a Messina e provincia, in «Scritti in onore di Salvatore Caronia», a cura della Facoltà di Architettura dell'Università di Palermo, Palermo 1966, pp.9-24.

- (in Italian) Giuffrè, M., Architettura in Sicilia nei secoli XV e XVI: le cappelle a cupola su nicchie fra tradizione e innovazione in "Storia architettura, n.2, Roma, 1996, pp. 33-48

- (in Italian) Gabriele di Battista Archived 2012-11-04 at the Wayback Machine scheda dell'Archivio biografico del Comune di Palermo. URL accessed 2 March 2011.

- (in Italian) Modello ricostruttivo della Tribuna di Antonello Gagini Archived 20 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Italian) André Chastel, I centri del Rinascimento, Milano, 1965, pag, 305-307.

- (in Italian) Giuseppina De Marco, Dal primo rinascimento all'ultima maniera. Marmi del Cinquecento nella provincia di Reggio Calabria, 2010, ISBN 9788890524400

- (in Italian) Elvira Natoli, Martino Montanini e la committenza francescana a Messina, in "Francescanesimo e Cultura nella provincia di Messina, 2009, pag.208. ISBN 88-88615-91-1

- Francesco Abbate, op. cit., 2001

- Anthony Blunt, Sicilian Baroque, 1968

- (in Italian) AA.VV.Fiamminghi e altri maestri, 2008, pag.86. ISBN 88-8265-510-5