Socioeconomic status and memory

Memory is one of the brain's most critical functions. It has the infinite ability to store information about events and experiences that occur constantly.[1] Experiences shape the way memories form, so major stressors on socioeconomic status can impact memory development. Socioeconomic status (SES) is a measurement of social standing based on income, education, and other factors.[2] Socioeconomic status can differ cross-culturally, but is also commonly seen within cultures themselves. It influences all spectrums of a child's life, including cognitive development, which is in a crucial and malleable state during early stages of childhood. In Canada, most children grow up in agreeable circumstances, however an unfortunate 8.1% are raised in households that fall into the category of low socioeconomic status. These children are at risk for many disadvantages in life, including deficits in memory processing, as well as problems in language development.[2]

Working Memory

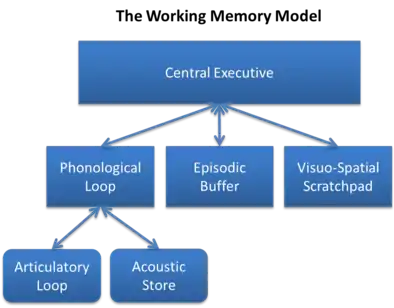

Working memory is a temporary storage system that is essential for the successful performance of the task at hand.[3]

Hippocampus

When creating new memories, the hippocampus and related structures of the brain play a key role in consolidation. Memory consolidation is the transformation of short-term memories to long-term memories,[3] which is crucial in the acquisition of new ideas. Until they can be stored more permanently, these memories are temporarily kept in the hippocampus in a process known as Standard Consolidation Theory. From childhood the hippocampus is developing, and it continues to mature beyond adolescents. A major barrier when it comes to studying working memory development in childhood is that much of the data come from adults who recall on past events of their childhood, and not from the children themselves.[4] This creates a problem in memory recall of those events that occurred when the hippocampus was still developing, and the working memory wasn't completely consolidated at the time. As people recall a former memory, the door to memory reconsolidation is opened. Reconsolidation refers to the retrieval of a memory from long-term storage to short-term working memory, where it is unstable and vulnerable to alteration.[3] As reported by Staff et al. (2012), socioeconomic status measured early in childhood reared a significant difference in hippocampal size in adulthood, suggesting that there is in fact an impact on brain and cognitive development.[5] Another study found that children from families with higher family income had larger anterior hippocampal volumes than children from families with lower family income, and this difference accounted for worse memory and language performance among children from families with lower family incomes.[6] Spatial memory is another specialized function of the brain, and more specifically, the hippocampus. Spatial memory refers to experiences that are recognized by their surrounding environment. Many of hippocampal neurons are in fact place cells. Place cells are neurons that are activated by certain locations or environments.[3] If a child is constantly in a maladaptive environment, their hippocampal neurons may be performing poorly, and memory development may be sacrificed.

Amygdala

The amygdala is another structure of the brain that is involved memory development. The amygdala's role in memory formation is to extract the emotional significance of experiences,[3] which may be positive or negative emotions. Children who grow up in positive households, develop to convey more positive emotions, than children who group up in negative households.[2] Lower socioeconomic status generally increases tension and negative emotions within a household, which may impact the emotional memory development of the children via the amygdala. A lack of positive emotional development may impact memory development as well as continual cognitive development in other areas, such as sociability and depression.

Child development and socioeconomic status (SES) are positively correlated, especially with regards to the child's working memory.[7] Low socioeconomic status environments with a high stress factor can increase the memory processing for a particular unpleasant event.[4] However, just because memory processes are firing, it doesn't mean that the information stored is valid or accurate. Stressful environments impair a child's memories and increase the probability for reconsolidation and contamination of false information. False memories are recollections of events that did not truly occur. Older children are most likely to confabulate these false memories and illusions, than younger children.[4] This may be because their memory and learning processes are more developed than younger children's’, which allows them to reconstruct memories based on real events as well as imaginary ones.

Parental Influence

Learning and memory go hand-in-hand, as one cannot occur without the other. Learning involves experiences and how they alter the brain, while memory focuses on how those changes in the brain are stored and recalled.[3] Lower socioeconomic status environments yield lower cognitive and intellectual development in children.[2] Since children cannot choose the environments that they are raised in, parental influence can greatly aid or inhibit a child's cognitive development. Low socioeconomic status due to poverty is a leading cause in hindered cognitive development in growing children. A constant inadequate diet throughout early childhood deprives the brain of the nourishment it requires to develop and function successfully.[2] Also affecting cognitive development is access to health care. Families with a low socioeconomic status cannot always afford necessary or beneficial health care for their children, which can hinder brain development, especially in later years when the brain is less likely to self-correct potential risk factors.[3] A lack of intellectual stimulation can also decrease cognitive development in children, which can occur in households with a low income, that cannot afford supplementary activities or programs for their children's developing minds. One of the most dynamic inhibitors of cognitive development by parental influence however, is parental violence and negativity. Children who live in high-risk environments of parental abuse express fluctuations in their ability of attentional skills due to constant fear or safety concerns.[8] Disturbance in attention can decrease both working memory and retrieval of long-term memories. If concentration is disturbed during recall, the memories that surface may be susceptible to reconsolidation, and the false memories that are created, due to lack of concentration, may solidify into inaccurate long-term memories. In a research model that looked at children living in environments of domestic violence and their relationship with memory, researchers found that children exposed to familial trauma displayed a poorer performance of working memory.[8]

Education

Low working memory is becoming more of an issue today with children in the public school system. The education system plays a substantial part in developing the children's mind for working memory. However, families who are in the low socio-economic status can't always afford private school to provide the children with the highest quality of teachers and learning. A disadvantage to having children in public school system is that educators don't have time, the right tools or proper techniques to train the children to develop better working memory. Public schools are at a disadvantage when it comes to receiving the best education for working memory.[9] Children who live in a low SES homes have difficulty learning how to develop and train the working memory. Working memory has slowly decreased over the growing years. Therefore, students become less motivated and have learning difficulties later on. Low working memory results in frustration, anger, being disruptive and failure to complete tasks.[10] Some effects to students having a low working memory is they can be very easily distracted, low attention span, as well as forgetfulness. Children that grow up in a higher SES, can afford to have a better education.

Language Development

Working memory gives the ability to keep languages, vocabulary and apt symbols readily available for communication with others and organization of thoughts. All of human kind utilizes language, and thus it has been widely recognized that children from areas of socioeconomic disadvantage are at high risk of delayed language development.[11] Parents from higher SES tend to be of higher education and therefore understand more about child development and the necessities for proper growth. For this reason, parents from high SES homes are more likely to see themselves as teacher figures and their children as students ready to learn.[12]

Children

Socioeconomic disadvantages have created unequal differences among educational attainments for children and families from various socioeconomic backgrounds. Differences between parent to child dialogue differs in homes of Low to High SES families. In homes of low SES children, there tends to be less direct conversation with the child, fewer opportunities of book reading and much less time shared between child and parent about the same subject or event.[13] This lack of dialogue slows the understanding of Syntax as children receive less opportunities to learn and understand the arrangement of their language.[14] In homes of high SES children, mothers tend to speak more freely with their children about emotions and feelings,[13] as well as attempt to directly follow up with what their children are saying. This proper and consistent verbal stimulation may add to a stronger verbal development than children from low SES families.

Considering language development is key for children to begin to convey themselves, grow and eventually detach from parents, it is important to display the differences among different socio-economic standings. In environments where children are spoken to and pushed practice words, first words tend to develop between 10–15 months.[2] North American Children are some of the most typically studied families, they come from middle-class families with mothers who influence language development. Mothers from these families often use object-labelling for their infants. This allows children to use phonological reference by giving meaning and association to the words spoken by their mothers.[2]

Children from low SES families who have had the unfair disadvantage of starting behind in language development do not tend to catch up, the delays may stay stable or increase in strength with age.[14] In adolescence these delays are still present in children from Low SES families. Studies with 13-14 year olds from High and Low SES areas have indeed suggested that delayed language development is still very apparent in children from low SES families.[6] Studies also found that children in areas of low SES were more likely than High SES children to have undetected language difficulties.[11] Considering children from low SES families may never catch up to children in High SES families it is important to detect language difficulties much earlier than adolescents. In adolescents language growth has slowed and dramatic language accomplishments are less likely to occur.[2]

Bilingualism

Bilingualism refers to the ability to use and understand two simultaneous languages. A bilingual person can for instance speak and understand both French and English. In 2011, Canadians recorded having 17% of the population being bilingual with 20% of them speaking a language other than French or English prior to learning French or English.[15] In relation to working memory and cognitive control, bilingual children have been found to achieve much higher scores than those of monolingual children.[16] Monolingual children have however outperformed bilinguals in standard vocabulary assessments.[17] Past research with High SES children suggests that both languages are constantly present in bilinguals and that this may account for the reduced efficiency in either language abilities.[17][18] Similar to monolinguals, Low SES bilingual children are at risk of under performing at one or both languages,[13][19] however there are exceptions, few outliers of Low SES children tend to achieve high proficiency scores in both languages.[19] Low SES children show preferential strength towards ethnic languages spoken at home.[19] Language development is largely dependent on parental interaction,[13] therefore children with monolingual parents struggle learning the second language due to a home environment which is restricted to their ethnic language.[19] However, if the parents are bilingual in the same languages, children are likely to out perform all bilingual children regardless of SES. Middle to High SES bilingual children have also been found to underachieve linguistically compared to Monolingual children of the same SES.[16] Middle to High SES children however show consistent higher proficiency than Low SES children at either language.[19]

Autism

The main diagnoses for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have issues with communication skills, social interactions and patterns of activity.[20] Children with high-functioning autism as well as low-functioning autism have impairments to their working memory, both verbal and non-verbal domains as well as language development.[21] Families with a child with ASD, and that are also in a higher socio-economic status (SES) often can provide more funding for the child to receive the proper treatment to help the child develop.[22] Families with a higher SES have access to better health care and behavior intervention programs to help the child develop normally. One of the treatments would include a program to help improve short-term, long-term and also, working memory. When children with ASD are at the early stages of development, working memory impairments is not always recognizable, consequently they do not get the appropriate training right away. Parents of children with ASD and are in the low SES group, they generally don't have the education or the resources to help the child with working memory impairment and language deficits.[22] Result of children with ASD had difficulties with short-term working memory, spatial working memory and also complex verbal memory.[21]

Durkin et al

Dr. Maureen Durkin, who is involved in the health sciences department at the University of Wisconsin, did a cross-sectional study to see if there was any correlation between children who are born with autism and socioeconomic status. This study was designed to see if socioeconomic status has any association with children who are born with autism spectrum disorder. Durkin and associates discovered that children born in low SES family and the births of autistic children are increasing. Although, there were some limitations to this study; ADDM Network surveillance system. Durkin et al. based their research on this system, it's a system where children with disabilities have access to diagnostic services. Therefore, autistic children in low SES, may not have access to the same. Another limitation this study has is that this study took part in children that were eight years old rather than when they were first diagnosed. This would have an effect on the outcome as some families who might be in a high SES, may use all the funds to help the child towards intervention programs and may leave the family in a low SES in the long run. Families that are in high SES, are well educated, and have the financial resources to pay for the highest quality of education for their child. Durkin et al. also found that good or low SES had to do with race and ethnicity.[23]

Working Memory Measures

Psychometrics

Scores on working memory measures have determined a strong association between working memory and language learning disabilities.[24] These measures are very useful in measuring a child's working memory and or learning disabilities. Research shows studies of working memory can predict a child's scholastic abilities for up to three years later.[25] Considering low SES is largely related to learning and language disabilities it is important to validate whether measures for such topics are free of socioeconomic influences.

The phonological loop is used by working memory to acquire and associate new vocabulary with existing vocabulary knowledge. Use of non-word repetition to measure the phonological loop has proven a strong predictor of learning disabilities in children learning language. These standardized language tests may pose more problems for children coming from Low SES families than children from Normal to High SES. Parent interaction, or the role of a caregiver in the home are of utmost important when developing vocabulary knowledge and strengthening the phonological loop.[2] Typically, in low SES homes parent interaction, extracurriculars and social environment are limited, this slows the child's development of vocabulary compared to children of normal to high SES. Working memory involves the memory system, which actively attends to gathering and organizing new information. It is a constant running memory system that aids memory storage and association.[2] Learning languages makes use of the working memory, however the strength of the working memory does not determine one's ability for vocabulary knowledge.[26] To distinguish children's scores between assessments, which study vocabulary, and those that study working memory, studies have had cohorts from both low SES and high SES families complete a battery of working memory measures.[26] Indeed, measurements of children's vocabulary knowledge reinforced past research on the impact a child's environment can have on their language learning. Measurements for non-word repetition and digit recall however showed no difference among scores between children of either High or Low SES. These findings dictate that measurements purely involved in working memory and not associated with vocabulary are free of socioeconomic influence. Working memory is unaffected by SES, however learning disabilities are still largely associated with Low SES.[26] Researchers can assume that working memory measurements are not biased to SES and can properly assess language development and other learning problems. The applicability of this knowledge proves especially useful in determining needs for early intervention in children's learning environments.

References

- Pinel, J.P.J., & Edwards, M. (2008). A colorful introduction to the anatomy of the human brain: A brain and psychology coloring book (2nd ed.). USA: Pearson.2

- Siegler, R., Eisenberg, N., DeLoache, J., Saffran, J., & Graham, S. (2014). How Children Develop (4th ed. New York: Worth.

- Pinel, J.P.J (2014). Biopsychology (9th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

- Howe, Mark L.; Cicchetti, Dante; Toth, Sheree L.; Cerrito, Beth M. (September 2004). "True and False Memories in Maltreated Children". Child Development. 75 (5): 1402–1417. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00748.x.

- Staff, Roger T.; Murray, Alison D.; Ahearn, Trevor S.; Mustafa, Nazahan; Fox, Helen C.; Whalley, Lawrence J. (May 2012). "Childhood socioeconomic status and adult brain size: Childhood socioeconomic status influences adult hippocampal size". Annals of Neurology. 71 (5): 653–660. doi:10.1002/ana.22631.

- Decker, Alexandra L.; Duncan, Katherine; Finn, Amy S.; Mabbott, Donald J. (August 12, 2020). "Children's family income is associated with cognitive function and volume of anterior not posterior hippocampus". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 4040. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17854-6. ISSN 2041-1723.

- Hackman, Daniel A.; Betancourt, Laura M.; Gallop, Robert; Romer, Daniel; Brodsky, Nancy L.; Hurt, Hallam; Farah, Martha J. (July 2014). "Mapping the Trajectory of Socioeconomic Disparity in Working Memory: Parental and Neighborhood Factors". Child Development. 85 (4): 1433–1445. doi:10.1111/cdev.12242. PMC 4107185.

- Gustafsson, Hanna C.; Coffman, Jennifer L.; Harris, Latonya S.; Langley, Hillary A.; Ornstein, Peter A.; Cox, Martha J. (2013). "Intimate partner violence and children's memory". Journal of Family Psychology. 27 (6): 937–944. doi:10.1037/a0034592. PMC 4041628.

- Engel de Abreu, P. J., Nikaedo, C., Abreu, N., Tourinho, C. J., Miranda, M. C., Bueno, O. A., & Martin, R. (2014). Working Memory Screening, School Context, and Socioeconomic Status: An Analysis of the Effectiveness of the Working Memory Rating Scale in Brazil. Journal of Attention Disorders, 18(4), 346.

- Davis, Nash; Sheldon, Linda; Colmar, Susan (September 27, 2013). "Memory Mates: A Classroom-Based Intervention to Improve Attention and Working Memory". Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling. 24 (1): 111–120. doi:10.1017/jgc.2013.23.

- Spencer, Sarah; Clegg, Judy; Stackhouse, Joy (May 2012). "Language and disadvantage: a comparison of the language abilities of adolescents from two different socioeconomic areas". International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 47 (3): 274–284. doi:10.1111/j.1460-6984.2011.00104.x.

- Johsnon, J., & Marting, C. (1985). Parents’ beliefs and home learning environments: Effects on cognitive development. In I.E. Single (Ed.), Parental belief systems: The psychological consequences for children (pp. 25-49). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum

- Garrett-Peters, Patricia; Mills-Koonce, Roger; Adkins, Daniel; Vernon-Feagans, Lynne; Cox, Martha (May 7, 2008). "Early Environmental Correlates of Maternal Emotion Talk". Parenting. 8 (2): 117–152. doi:10.1080/15295190802058900. PMC 2783602.

- Hoff, Erika (October 2003). "The Specificity of Environmental Influence: Socioeconomic Status Affects Early Vocabulary Development Via Maternal Speech". Child Development. 74 (5): 1368–1378. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00612.

- Statistics Canada. (2012a). 2011 census of population: Linguistic Characteristics of Canadians. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/121024/dq121024a-eng.htm

- Morton, J. Bruce; Harper, Sarah N. (November 2007). "What did Simon say? Revisiting the bilingual advantage". Developmental Science. 10 (6): 719–726. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00623.x.

- Engel de Abreu, Pascale M. J. (July 2011). "Working memory in multilingual children: Is there a bilingual effect?". Memory. 19 (5): 529–537. doi:10.1080/09658211.2011.590504.

- Costa, A., Roelstraete, B., & Hartsuiker, R. (2006). The lexical bas effect in bilingual speech production: Evidence for feedback between lexical and sub lexical levels across languages. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 13, 612-617.

- Dixon, L. Quentin; Wu, Shuang; Daraghmeh, Ahlam (December 6, 2011). "Profiles in Bilingualism: Factors Influencing Kindergartners' Language Proficiency". Early Childhood Education Journal. 40 (1): 25–34. doi:10.1007/s10643-011-0491-8.

- Gabig, C. (2008). Verbal working memory and story retelling in school-age children with autism. Language, Speech & Hearing Services In Schools, 39(4), 498-511.

- Schuh, Jillian M.; Eigsti, Inge-Marie (November 2, 2012). "Working Memory, Language Skills, and Autism Symptomatology". Behavioral Sciences. 2 (4): 207–218. doi:10.3390/bs2040207.

- Thomas, P., Zahorodny, W., Peng, B., Kim, S., Jani, N., Halperin, W., & Brimacombe, M. (2012). The Association of Autism Diagnosis with Socioeconomic Status. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 16(2), 201-213.

- Durkin, Maureen S.; Maenner, Matthew J.; Meaney, F. John; Levy, Susan E.; DiGuiseppi, Carolyn; Nicholas, Joyce S.; Kirby, Russell S.; Pinto-Martin, Jennifer A.; Schieve, Laura A.; Myer, Landon (July 12, 2010). "Socioeconomic Inequality in the Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Evidence from a U.S. Cross-Sectional Study". PLoS ONE. 5 (7): e11551. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011551.

- Archibald, L. M.D., & Gathercole, S.E. (2006). Nonword repetition: a comparison of tests. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 87, 85-106.

- Gathercole, S. E., Brown, L., & Pickering, S. J. (2003). Working memory assessments at school entry as longitudinal predictors of National Curriculum attainment levels. Educational and Child Psychology, 20, 109-122

- Engel, Pascale Marguerite Josiane; Santos, Flávia Heloísa; Gathercole, Susan Elizabeth (December 2008). "Are Working Memory Measures Free of Socioeconomic Influence?". Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 51 (6): 1580–1587. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0210).