Solentiname Islands

The Solentiname Islands (Spanish pronunciation: [solentiˈname]) are an archipelago towards the southern end of Lake Nicaragua (also known as Lake Cocibolca) in the Nicaraguan department of Río San Juan.

Solentiname Islands | |

|---|---|

Municipality | |

The Solentiname Islands (in violet) | |

Solentiname Islands Location in Nicaragua | |

| Coordinates: 11°12′N 85°2′W | |

| Country | |

| Department | Río San Juan |

| Area | |

| • Total | 70 sq mi (190 km2) |

| • Land | 15 sq mi (38 km2) |

| Elevation | 843 ft (257 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,000 |

| • Density | 14/sq mi (5.3/km2) |

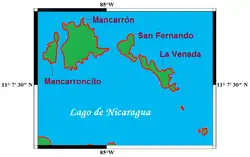

They are made up of four larger islands, each a few kilometres across, named, from west to east, Mancarroncito, Mancarrón, San Fernando and La Venada, along with some 32 smaller islands with rocky headlands which afford shelter to numerous aquatic birds. The islands’ origins are volcanic. The highest point in the islands is found on Mancarrón; it is 257 m (843 ft) above sea level. The Solentiname Islands are a National Monument. They constitute one of the 78 protected areas of Nicaragua.

History

There is some confusion over what the archipelago's name means. Some hold that it is from a Nahuatl word that means "covey of quail", and others say that it comes from the Nahuatl word Celentinametl, which means "place of many guests". The latter opinion is found in the majority of sources.

Geography

The Solentiname Islands are tropical in every sense. They are covered in tropical tree species, transitional between wet and dry tropical, and are home to various colourful bird species, including various kinds of parrot and toucans; there are 76 species in all. The waters about the islands contain plentiful fish. There are about 46 species, including tarpon, freshwater sharks, sawfish, and swordfish. The island of La Venada is known for its deer, and also named for them (La Venada is Spanish for "The Doe").

The yearly rainfall in the islands measures between 1,400 and 1,800 mm (55 and 71 in), with most of it falling between May and December. Solentiname's mean yearly temperature is 26 °C (79 °F).

The islands’ tranquility and colourfulness are likely what has attracted artists to their shores. Painters and woodcarvers share the islands with farmers and fishermen. The archipelago's population is less than 1000, and its land area is about 38 km2 (15 sq mi). Modern amenities, including electricity and running water, are quite rare in the islands.

Mancarrón is Solentiname's largest island. It is here that the priest and poet Ernesto Cardenal’s historical parish is to be found. Father Cardenal arrived in the islands in 1966 and is known for establishing a communal society for artists in the early 1970s which persists to this day. The community developed its own naïve art movement based on existing folk forms, and with some help from painter Róger Pérez de la Rocha. There is a small art gallery where the craftsmen and painters display their works: birds, mobiles featuring the local fauna carved out of balsawood, as well as much sought-after colourful primitivist Solentiname paintings, largely inspired by the islands’ rich wildlife and plant species.

Painters resident at the art colony included Asilia Guillén.[1]

Tourism and economy

For these very things, the Solentiname Islands have also been the object of ecotourism in recent years, although currently, they are still a somewhat obscure destination. However, there are now three hotels in the islands, two of which are quite new.

There are also important archaeological sites (including petroglyphs on San Fernando featuring images of parrots, monkeys, and people), the Los Guatuzos Wildlife Refuge, a 400 km2 (150 sq mi) marsh parallel to the lakeshore, home to both monkeys and alligators, and the Solentiname National Monument, which consists of the islands themselves and the lakeshores around them.

Solentiname's agricultural products include avocado, cotton, sesame, corn, coffee and cacao.

Parts of the story "Apocalipsis de Solentiname" by Julio Cortázar are set on the Solentiname Islands. The story features Ernesto Cardenal as a character, as well as the community's small art gallery.

References

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Solentiname Islands. |