Special education in China

Special education in China provides education for all disabled students.

Demographics

According to the 2006 census, 82.96 million disabled people live in China, an estimated 6.34% of the overall population. This statistic had a 1.44% increase from the year 1987. Men outnumber women in China’s 1.35 billion population making it no surprise that more than half of the people with disabilities are male. The number of disabled people living in the rural areas of China is 75% of the disabled population, compared to the urban which held 25% of the disabled population. Specifically relating to school-aged population, disabled children at the age between 6-14 reached to 2.46 million, 2.96% of the total disabled population. Less than 3% of China’s disabled population is in the school-aged demographic. Although this statistic is shockingly low, the one child policy contributes to much of the population decreases seen in recent history especially among school-aged children.[1] China categorizes disabilities differently than in other nations, for example China identified 5% of their school-aged population to be in need of special education whereas The United States identified 10% of their school-aged population; this comparison is a result of China not recognizing learning disabilities or disorders such as ADHD to be in need of special services whereas many other nations do.[2] Educational opportunities for disabled Chinese are lacking, causing elevated poverty and poor living conditions .

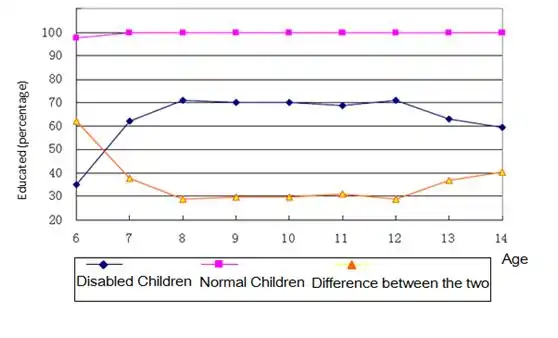

As the chart indicates approximately 60%-70% of disabled children are educated, contrasted with close to 100% for the able-bodied. Only 25% of disabled children enroll in high schools or higher educational institutions.[3]

Historical background

Due to the views held regarding Confucianism, people with disabilities have been respected and considered part of society throughout Chinese history. Throughout Chinese history citizens with disabilities did not have high social status due to their physical or mental characteristics which limited their abilities to climb socially. Instead of viewing the minorities as equals, the Chinese people sympathized and pitied those with disabilities. Although there were many who wished to help disabled people, “institutions for educating individuals with disabilities were not established during the feudal dynasties that lasted more than 2,000 years”(Deng, Meng, McBrayer, & Farnsworth 289).

In the recent history of China, the most prominent influence in the beginning of special education was Mao Zedong. Improvement in the education system for children with disabilities was close to nothing until the twentieth century during Mao’s time of power. “Under the Maoist philosophy, people with disabilities had been treated as equal members of society who could make contributions to the Socialist country. This promoted social awareness and acceptance of disability” (Deng, Meng, Mcbrayer, & Farnsworth 290). The most paramount change seen in this time period was in 1951, when the Chinese Political Council established The Decision to Reform the Education System, “which explicitly required governments at all levels to establish schools for individuals with visual and hearing impairments and to provide education for children, adolescents, and adults with physical disabilities. This document, for the first time in Chinese education history, included special education in the formal public education system and advocated the legislation for special teacher education (Wang, Yan, and Mu 350). Results of this reformation led to “the number of schools and enrolled students with disabilities increas[ing] to 57 and 5,312, respectively, in 1955, and to 479 and 26,701, respectively, by 1960” (Deng, Meng, Mcbrayer, & Farnworth 290). However, these increases did not last long and were strongly affected by the Cultural Revolution in 1966. This occurrence had a negative effect on special education growth based on political and economic insufficiencies of that time. The newly formed special education schools under Mao’s rule suffered greatly “with many schools closing and the number of students falling from 1,176 before 1966 to 600 by 1976” (Deng, Meng, Mcbrayer, & Farnworth 291). Mao can be placed responsible for the increase of special education and ultimately the halt on special education practices in China.

Services

Few educational institutions serve special needs students. As of 2018, around 1710 institutions specifically serve disabled people, with forty-six thousand teaching staff spread across those institutions. In China, students with disabilities are usually separated from typical classrooms and placed in schools dedicated to special education. The first school dedicated to students with disabilities in China was established in 1987 in the city of Beijing. Currently this school has 60 staff members who teach more than 200 children in 17 classrooms. The school provides professional development and resource centers and an intensive diagnostic and training center for 3- and 4-year-olds with autism, as well as special education classes for school-age children". The school is described as being very academic however the students are involved in active activities and plenty of one on one time with their instructors. The school also recruits students from all around China due to the scarcity of special education schools across the country.[4] Segregation in education is what is typically seen within special education in China, however China has begun to adopt the idea of classroom inclusion which has proven to be beneficial in other nations who have adopted the method. Although this strategy is fairly new in China it has already shown positive results “Between 1987 and 1996, the school entrance rate of students with disabilities rose from 6% to 60%, and a large majority of these students were in general education classrooms.” Meaning students with special needs are being placed in typical classrooms with specialized instruction being given to students who have varying needs.[5]

Special teacher education has seen a large increase in the last decade “Conversations with teacher educators or trainers at Beijing Normal University and East China Normal University indicated that programs to prepare special education teachers are developing rapidly. Several teachers mentioned that rigorous examinations still are the most important determining criteria for accepting teacher candidates to teacher training programs” (Ellsworth and Zhang 63). However, there is still a large gap between the number of students in need and the qualified teachers to provide services. There has also been issues with the universities in China not providing special education programs in their schools, only limited schools in the urban areas provide this line of study, making the qualification for special educators hard to come by.[6]

Employment

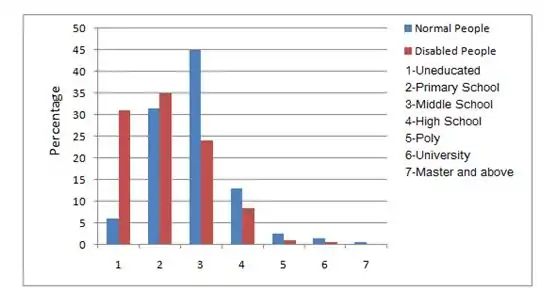

An issue directly related to education is the employment rate. Some researchers report that more than 10% of the disabled people in China lack adequate food and clothing, about 40% have very little income and only 25% work on a full-time basis. Among those who are employed, 96.6% are manual workers. Employment status has a direct correlation with income. Families without a disabled person have an average 23.26% higher family income than families with at least one disabled person

References

- "Facts on People with Disabilities in China." (2006): 1+. International Labor Organization. The United Nations. Web.

- Deng, Meng, Kim Fong Poon-Mcburger, and Elizabeth B. Farnsworth (2001). The Development of Special Education in China: A Social Cultural Review. Page 288-298. Sage Journals. Web. Remedial and Special Education. Print.

- 海洁, 尹. "残疾人的受教育状况:公平缺失与水平滑坡" (PDF). Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- Ellsworth, Nancy J., and Zhang Chung. "Progress And Challenges In China's Special Education Development: Observations, Reflections, And Recommendations." Remedial & Special Education 28.1 (2007): 58-64. Academic Search Complete. Web. 13 Nov. 2016

- Chen Zhang, Kaili. "Which Agenda? Inclusion Movement And Its Impact On Early Childhood Education In Hong Kong." Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 38.2 (2013): 111-121. Academic Search Complete. Web. 13 Nov. 2016.

- Wang, Yan, and Guanglun Michael Mu. "Revisiting The Trajectories Of Special Teacher Education In China Through Policy And Practice." International Journal of Disability, Development & Education 61.4 (2014): 346-361. Academic Search Complete. Web.