St Giles' Church, Cambridge

The Church of St Giles is a Grade II*-listed church in Cambridge, England.[1] It is a Church of England parish church in the Parish of the Ascension of the Diocese of Ely, located on the junction of Castle Street and Chesterton Road. It was completed and consecrated by the Bishop of Ely in 1875, to replace an earlier church founded in 1092. The church, which added "with St Peter" to its appellation when the neighbouring St Peter's Church became redundant, is home to both an Anglican and a Romanian Orthodox congregation[2] and is used as a venue for concerts and other events.[3] It also serves as a main location of the Cambridge Churches Homeless Project.

| St Giles' Church | |

|---|---|

| The Church of St Giles with St Peter | |

The Church of St Giles, Cambridge | |

| |

| Location | Castle Street, Cambridge CB3 0AQ |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Website | www |

| History | |

| Consecrated | 1092 |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Grade II* listed |

| Style | Victorian Gothic |

| Years built | 1875 |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Ely |

| Clergy | |

| Rector | The Rev'd Canon Philipa King |

The war memorial in the churchyard, designed by Bodley and Hare and unveiled in 1920, is Grade II-listed.[4]

History

Foundation

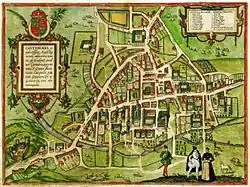

St Giles' Church was founded in 1092 by an endowment from Hugolina de Gernon, the wife of Picot of Cambridge, baron of Bourn and county sheriff.[5] According to the 12th-century writings of Alfred of Beverley, Hugolina, who had been suffering from a long illness which the king's physician and other doctors had been unable to treat, had prayed to Saint Giles on her death bed promising to build a church in his honour if she were to recover, which she duly did. Picot reportedly constituted the church, after consulting with the Archbishop of Canterbury, Anselm, and the Bishop of Lincoln, Remigius de Fécamp, under the supervision of the Canon of Huntingdon and his own patronage against the curtain walls of his home at Cambridge Castle.[6][7] Former county archaeologist Alison Taylor, however, speculates that, rather than founding a new priory, Picot placed an existing minster serving the area in control of the Norman Canons Regular, and that this was done for purely economic reasons.[7][8]

The church was initially served by a group of six Augustinian canons, who remained at St Giles' for twenty years until after the death of Picot, when they were granted land in Chesterton by Pain Peverel upon which they established Barnwell Priory. The small St Giles' Church continued to operate over the following centuries but failed to develop due to its impoverished location outside the town walls in a densely inhabited area that was badly affected by the Black Death.[5]

Under Queen Elizabeth I, the rectory and advowson were granted to the Bishop of Ely in 1562. The church's register of baptisms begins in 1596, those of marriages and burials in 1607, and the churchwardens' accounts in 1620.[9]

The land within the parish boundary of St Giles (about 1,370 acres) remained largely unenclosed until the beginning of the 19th century. Under the enclosure act of 1802, thirty-three acres went to the Vicar of St Giles, in compensation for the loss of small tithes, and 165 acres to the Bishop of Ely, as an "appropriator of the Rectory of St Giles", in compensation for great tithes. More than half the enclosed land went to the colleges, and remained largely as pasture until the 1870s.[10]

Reconstruction

The original structure of the medieval church became almost entirely obscured or pulled down by a large post-Reformation extension and the addition of box pews. Early in the 19th century the vicar, William Farish (third Jacksonian Professor of Natural Philosophy) enlarged the accommodation from 100 to 600 seats.[9]

According to former county archaeologist Alison Taylor, the church was serving the impoverished and fast-growing community of the upper town,[11] in the neighbourhood of the castle mound, and its shire hall (assize court) (1842) and prison, when a new building was planned, incorporating elements from the previous church.[7][12] The new Victorian building, standing a little north of the one it replaced, was erected to the design of T. H. and F. Healey, architects, of Bradford. In the new church, the early 12th-century chancel arch of the older church was reset between the south aisle and the south chapel, and a late 12th-century doorway was reset between the north aisle and the vestry.[1] The stone Carr Monument (early 17c.), commemorating Nicholas Carr, appointed the University's second Regius Professor of Geek in 1547, was reset in the south wall of the south chapel (the Lady Chapel).[7][13]

Revival

The church is constructed of brick with Doulton stone dressings and a Westmorland slate roof. Inside, at the High Altar, the original reredos can be glimpsed behind the current triptych. It shows the resurrection appearance of Christ to the apostles on the shores of the Sea of Galilee. The triptych was installed at the turn of the century (19th to 20th).[14]

Historic England, recording St Giles' Grade II*-listed status, describes it as being "of outstanding quality by virtue of its collection of medieval and C18 survivals, together with C19 fittings by many of England's leading church decorators".[1] The interior was decorated in the style favoured by the Oxford Revival,[15] with Sir Charles Kempe and Sir Ninian Comper commissioned to provide much of the design work,[16] and the church still houses works after Michelangelo and a copy of Chatsworth House version of the Adoration of the Magi by Paolo Veronese. Much of the wood carvings were supplied in the late 19th century by Bavarian wood-carvers from Oberammergau. The altar rails came from the English Church in Rotterdam.

The eighteen stained glass windows of the nave by Robert Turnhill of Heaton, Butler and Bayne, arranged in chronological sequence, begin with Saint Clement of Rome and eight others, which were installed in 1888 on the south side, and end with Samuel Seabury, installed with eight others on the north side later.[17]

Team ministry

The church is now part of a team ministry benefice,[18] for St Giles with St Peter; St Luke the Evangelist (Victoria Road) and St Augustine's (Richmond Road).[19]

References

- Historic England. "Church of St Giles (1331828)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2015-11-10.

- "St John the Evangelist Romanian Orthodox Parish in Cambridge, UK". Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- "St Giles w St Peter, Cambridge". A Church Near You. Retrieved 2015-09-03.

- Historic England. "St Giles War Memorial (1428626)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- "St Giles Church: A Brief History" (PDF). Church at Castle. Retrieved 2015-09-03.

- Codd, Daniel (2010), "Signs & Wonders: A Prayer to St. Giles", Mysterious Cambridgeshire, JMD Media, ISBN 9781859838082

- Taylor, Alison (1999), "Medieval Religious Houses in the Town", Cambridge: The Hidden History, Tempus, ISBN 9780752414362

- Taylor, Alison (1999), "Cemeteries and Re-Growth: The Anglo-Saxon Period", Cambridge: The Hidden History, Tempus, ISBN 9780752414362

- BHO The city of Cambridge: Churches

- Philomena Guillebaud, The Enclosure of Cambridge St Giles: Cambridge University and the Parliamentary Act of 1802.

- Taylor, Alison (1999), "The Later Town", Cambridge: The Hidden History, Tempus, ISBN 9780752414362

- 'The New Saint Giles', in A Brief History

- St Giles' Church A Brief History

- Saint Giles' Church, "The Chancel"

- "History - Friends of St Giles' Church, Cambridge". www.fosgc.org. Retrieved 2015-11-10.

- "Art & Architecture - Friends of St Giles' Church, Cambridge". www.fosgc.org. Retrieved 2015-11-10.

- Sylvia Pick, The Nave Windows of St Giles, Cambridge, 2014

- "Diocese of Ely". Archived from the original on 1 June 2016.

- "Our Churches". Churchatcastle.org. Retrieved 8 October 2019.