St Stephen's Chapel

St Stephen's Chapel, sometimes called the Royal Chapel of St Stephen, was a chapel in the old Palace of Westminster which served as the chamber of the House of Commons of England and that of Great Britain from 1547 to 1834. It was largely destroyed in the fire of 1834, but the Chapel of St Mary Undercroft in the crypt survived.

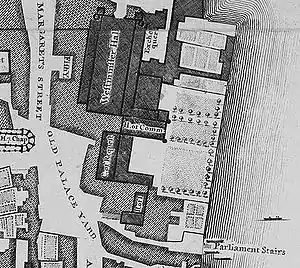

The present-day St Stephen's Hall and its porch, which are within the new Palace of Westminster built in the 19th century, stand on exactly the same site and are today accessed through the St Stephen's Entrance, the public entrance of the House of Commons.

History

As a Royal Chapel

According to Cooke (1987), King Henry III witnessed the consecration of the Sainte Chapelle in Paris in 1248, and wished to construct a chapel in his principal palace at Westminster to rival it. Work continued for many years under Henry's successors, to be completed around 1297.[1] In the resulting two-storey chapel, the Upper Chapel was used by the Royal Family, and the Lower Chapel, by the Royal Household and courtiers.

Historical events

Two royal weddings are recorded as having been solemnised in St Stephen's Chapel. On 20 January 1382, King Richard II was married to Anne of Bohemia. The bridegroom was fifteen, the bride sixteen.[2] The other marriage occurred on 15 January 1478, between the younger of the two Princes in the Tower, Richard, Duke of York, and Anne Mowbray.[3] Being four years old, she was a year younger than Richard. At the age of eight, Anne died. Her coffin was discovered in a vault in Stepney in 1964, and her remains reinterred in Westminster Abbey.[3] The body of Richard's father, King Edward IV, who died at the Palace of Westminster on 9 April 1483, was conveyed to St Stephen's Chapel the next day, and lay in state there for eight days before his interment at St George's Chapel, Windsor.[4]

Thomas Cranmer was consecrated in St Stephen's Chapel as Archbishop of Canterbury on 30 March, 1533.[5] After the death of King Henry VIII the Palace of Westminster ceased to be a royal residence. Henry's son, King Edward VI, instituted the Abolition of Chantries Act 1547 and St Stephen's Chapel thus became available for use as the debating chamber of the House of Commons.[6] Oliver Cromwell had the crypt whitewashed and used it to stable his horses.[7]

On the night before the 1911 census, women's suffragist Emily Davison spent the night in a broom cupboard in the back of the crypt in order to be able to give her address as the House of Commons, despite not being allowed to stand for Parliament or vote.[8] A plaque was unofficially placed in the cupboard to commemorate this in around 1991 by the late Tony Benn MP. He put the plaque in place with his own hands and proudly showed it to visitors. He later installed a second plaque for a purpose which is now lost but the Palace authorities required him to remove it. The screw holes are still visible.

As the House of Commons chamber

The former chapel's layout and functionality influenced the positioning of furniture and the seating of Members of Parliament in the Commons. The Speaker's chair was placed on the altar steps – arguably the origin of the tradition of members bowing to the Speaker, as they would formerly have done to the altar. Where the lectern had once been, the Table of the House was installed. The members sat facing one another in the medieval choir stalls, creating the adversarial seating plan that persists in the chamber of the Commons to this day. The old choir screen, with its two side-by-side entrances, was also retained and formed the basis of the modern voting system for parliamentarians, with "aye" voters passing through the right-hand door and "no" voters passing through the left-hand one.[10]

In order to suit the needs of the House of Commons, various changes to the chapel's original Gothic form were made by various architects between 1547 and 1834. Initial changes during the late 16th Century were relatively minor; the original chapel furnishings were replaced, the interior whitewashed and the stained-glass windows replaced with plain glass. More drastic alterations were undertaken by Christopher Wren in the 1690s. During that work the building was significantly reduced in height with the removal of the clerestory and vaulted ceiling while the great medieval windows were walled up, with smaller windows cut into the new stonework. Inside, the walls were reduced in thickness to accommodate extra seating and the addition of upper-level male-only public galleries along both sides of the chamber, and the remains of the medieval interior were concealed behind wainscoting and oak panelling. A false ceiling was installed in the chamber to help to improve its acoustics, the quality of which was important in an age without artificial amplification. The newly created attic space above the ceiling housed a ventilation lantern and was used as the ladies' gallery, although the view down into the chamber beneath through the lantern was severely restricted. More seating was later added for the extra members brought in by the Acts of Union with Scotland (1707) and Ireland (1800). By the 19th century, the chapel's interior had a very bland and modest look in contrast to its former medieval magnificence.[11] Further alterations were made to the exterior by James Wyatt at the end of the 18th Century.

Fire and reconstruction

The fire of 1834 totally destroyed the main body of the chapel, with the crypt below, and the adjoining cloisters, barely surviving. Amongst the few furnishings rescued from the flames was the Table of the House, which is now kept in the Speaker's apartments at the palace. Although it was demolished shortly after the fire, the surviving stone shell of the chapel, with all its later additions burned away, attracted many visitors and antiquaries who came to view the original medieval decorations which had become visible once again. The historical importance of the chapel was realised in the design of the new palace in the form of St Stephen's Hall, the lavishly decorated main public entrance hall built on the same floor plan as the old chapel, with the position of the Speaker's chair marked out on the floor.[12]

The crypt below St Stephen's Hall, the Chapel of St Mary Undercroft, which had fallen into disuse some time before the fire and had seen a number of uses, was restored, and returned to its original use as a place of worship. It is still used for this purpose today. Children of peers, who possess the style of "The Honourable", have the privilege of being able to use it as a wedding venue. Members of Parliament and peers have the right to use the chapel as a place of christening.[13]

The body of Margaret Thatcher was kept in St Mary Undercroft on the night before her funeral on 17 April 2013.[14]

Further reading

- Maurice Hastings, St Stephen's Chapel and its Place in the Development of Perpendicular Style in England (1955)

- Sir Robert Cooke, The Palace of Westminster (London: Burton Skira, 1987)

References

- John Steane, The Archaeology of Medieval England and Wales (1985, ISBN 0709923856), p. 7

- Anne of Bohemia Archived 2011-09-20 at the Wayback Machine, Reformation Society website. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- Anne Mowbray, Duchess of York from Westminster Abbey website. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- "1483-The Year of Three Kings". Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- Stephen Taylor, From Cranmer to Davidson: A Church of England Miscellany (1999, ISBN 0851157424), p. 3

- Kenneth R. Mackenzie, Parliament (1962), p. 29

- The gentleman's magazine and historical chronicle, vol. 80, Part 1 (1810), p. 4

- William Kent, An Encyclopaedia of London (1951), p. 639

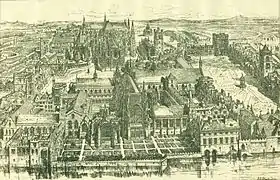

- The bird's-eye view by H. J. Brewer was published in The Builder in 1884, according to www.parliament.uk.

- Kim Dovey, Framing Places: Mediting Power in Built Form (1999), p. 87

- Anthony Emery, Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500, vol. 3 (2006), p. 256

- J. N. Spellen, The Inner Life of the House of Commons (1854), p. 6

- Emma Crewe, Lords of Parliament: Manners, Rituals and Politics (2005, ISBN 0719072077), p. 97

- BBC News 16-4-13

External links

- explore-parliament.net – shows various views of the chapel, notably this image.

- https://www.virtualststephens.org.uk/ - including a section on 'Visualizing St Stephens' throughout its history