Stenberg brothers

Vladimir Stenberg (April 4 [O.S. March 23] 1899 – May 1, 1982) and Georgii Stenberg ( October 7 [O.S. October 20] 1900 – October 15, 1933) were Soviet artists and designers.

Biographies and works

The Stenberg brothers, whose father was a Swede and whose mother was a Latvian, were both born in Moscow, Russia but remained Swedish citizens until 1933. They first studied engineering, then attended the Stroganov School of Applied Art in Moscow, 1912–1917, and subsequently the Moscow Svomas (free studios), where they and other students designed decorations and posters for the first May Day celebration (1918). 1919, the Stenbergs and comrades founded the OBMOKhU (Society of Young Artists) and participated in its first group exhibition in Moscow in May 1919 and in the exhibitions of 1920, 1921 and 1923. The brothers and Konstantin Medunetskii staged their own "Constructivists" exhibition in January 1922 at the Poets Café Moscow, accompanied by a Constructivist manifesto. Also that year, Vladimir showed his work in the landmark Erste Russische Kunstausstellung (First Russian Art Exhibition) held in Berlin. 1920s–1930s, they were well established as members of the avant-garde in Moscow and of Moscow's INKhUK (INstitut KHUdozhestvennoy Kultury, or institute of artistic culture). Other INKhUK members included Alexander Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova, Lyubov Popova, Medunetskii, other artists, architects, theoreticians, and art historians. INKhUK was active only 1921–1924.

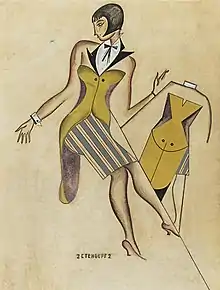

1922–1931, the Stenbergs designed sets and costumes for Alexander Tairov's Moscow Kamerny (Chamber) theatre and contributed to LEF (art journal of the left front) and to the 1925 "Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes" in Paris. 1929–32, they taught at the Architecture-Construction Institute, Moscow.

The Stenbergs practiced in a range of media, initially active as Constructivist sculptors, subsequently as theater designers, architects, and draftspeople. Their design work covered the gamut from clothing, including women's shoes, to rail carriages. Some examples of their sculpture were spidery and spindly structures, such as the reconstruction (1973–1974) of KPS 11: Construction of a spatial apparatus no. 11 (1919–1920) in steel, glass, paint and plaster on wood in the National Gallery of Australia Canberra. However, the arenas in which they excelled were theater, costume and graphic designs, particularly the graphic design of film posters, encouraged by the surging interest in movies in Russia and the government's sanctioning of graphic design and the cinema.

The brothers were at their prime during the revolutionary period of politics and artistic experimentation in Russia, centered in Moscow. There was a shift from the illustrator-as-creator to the constructor-as-creator or nonlinear-narrator-as-creator. In the visual language of the constructor or Constructivist, the Stenbergs and other graphic designers and artists assembled images, such as portions of photographs and preprinted paper, that had been created by others. Thus, the Stenbergs and others realized wholly new images (or compositions) which were no longer about realism. Hence, graphic design as a modern expression eschewing traditional fine art was born in the form of the printed reproductions of collage or assemblage. One of the causes of the avant-garde artists in the new Russia, who considered fine art to be useless, was served when the Stenbergs and others as constructors-as-creators produced posters that had a use, particularly to serve the state. (In fact, painter Nadezhda Udaltsova resigned from the UNKhUK in protest against the replacement of easel painting by use-intended industrial art.)

The serendipitous success of the Stenbergs' radical approach had been facilitated by a number of factors: their talent as graphic designers and their knowledge of film theory, Constructivism, Malevich's Suprematism, and the avant-garde theater. Even though commercial graphic design and advertising is propaganda, the dissemination of propaganda (пропаганды) was considered a desirable and honorable practice in Russia at the time. In fact, the Bolsheviks, who sought to reform the peasant class, considered film to be a potent propaganda tool for communicating with a widely illiterate population. Even though most films were imported, the Stenbergs designed posters for Sergei Eisenstein's movies and Dziga Vertov's documentaries.

The innovative visual aspects of Stenberg posters included a distortion of perspective, elements from Dada photomontage, an exaggerated scale, a sense of movement, and a dynamic use of color and typography—eventually all were to be imitated by others. The Stenberg artwork was frequently based on stills from the films. Radical even today, the posters by the brothers working together were realized within the nine-year period from 1924 to 1933, the year Georgii died at age 33. His motorcycle hit a truck, a few months after the brothers had become Russian citizens. Vladimir continued to work on film posters and organized the decorations of Moscow's Red Square for the May Day celebration of 1947.

Exhibition

Current exhibition 'KINO/FILM. SOVIET POSTERS OF THE SILENT SCREEN' 17-4a Little Portland Street London W1W 7JB Free admission.

- Traveling exhibition, "Stenberg Brothers: Constructing a Revolution in Soviet Design", organized by The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and shown there initially June 10–September 2, 1997

Auction record

On May 3, 2010 Swann Galleries sold the Stenberg Brothers' poster for a run of performances by the Theatre Karmeny de Moscou in Paris in 1923 for an auction record price of $9,600. The poster is the only one by the Stenbergs ever produced for use outside of the Soviet Union.

References

- Christopher Mount and Peter Kenez (1997). Stenberg Brothers: Constructing a Revolution in Soviet Design, New York: The Museum of Modern Art. | ISBN 0-87070-051-0

- Review of the New York exhibition and biographical information, Kimmelman, Michael (June 13, 1997). "Mementos of a Revolution Repressed", The New York Times