Strain gauge

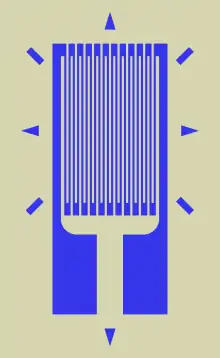

A strain gauge (also spelled strain gage) is a device used to measure strain on an object. Invented by Edward E. Simmons and Arthur C. Ruge in 1938, the most common type of strain gauge consists of an insulating flexible backing which supports a metallic foil pattern. The gauge is attached to the object by a suitable adhesive, such as cyanoacrylate.[1] As the object is deformed, the foil is deformed, causing its electrical resistance to change. This resistance change, usually measured using a Wheatstone bridge, is related to the strain by the quantity known as the gauge factor.

Physical operation

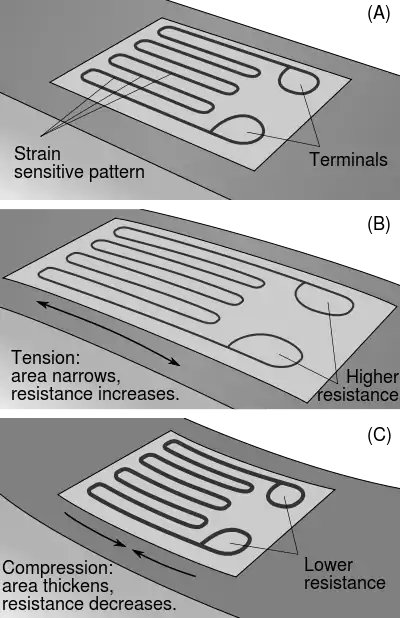

A strain gauge takes advantage of the physical property of electrical conductance and its dependence on the conductor's geometry. When an electrical conductor is stretched within the limits of its elasticity such that it does not break or permanently deform, it will become narrower and longer, which increases its electrical resistance end-to-end. Conversely, when a conductor is compressed such that it does not buckle, it will broaden and shorten, which decreases its electrical resistance end-to-end. From the measured electrical resistance of the strain gauge, the amount of induced stress may be inferred.

A typical strain gauge arranges a long, thin conductive strip in a zig-zag pattern of parallel lines. This does not increase the sensitivity, since the percentage change in resistance for a given strain for the entire zig-zag is the same as for any single trace. A single linear trace would have to be extremely thin, hence liable to overheating (which would change its resistance and cause it to expand), or would need to be operated at a much lower voltage, making it difficult to measure resistance changes accurately.

Gauge factor

The gauge factor is defined as:

where

- is the change in resistance caused by strain,

- is the resistance of the undeformed gauge, and

- is strain.

For common metallic foil gauges, the gauge factor is usually a little over 2.[2] For a single active gauge and three dummy resistors of the same resistance about the active gauge in a balanced Wheatstone bridge configuration, the output sensor voltage from the bridge is approximately:

where

- is the bridge excitation voltage.

Foil gauges typically have active areas of about 2–10 mm2 in size. With careful installation, the correct gauge, and the correct adhesive, strains up to at least 10% can be measured.

In practice

An excitation voltage is applied to input leads of the gauge network, and a voltage reading is taken from the output leads. Typical input voltages are 5 V or 12 V and typical output readings are in millivolts.

Foil strain gauges are used in many situations. Different applications place different requirements on the gauge. In most cases the orientation of the strain gauge is significant.

Gauges attached to a load cell would normally be expected to remain stable over a period of years, if not decades; while those used to measure response in a dynamic experiment may only need to remain attached to the object for a few days, be energized for less than an hour, and operate for less than a second.

Strain gauges are attached to the substrate with a special glue. The type of glue depends on the required lifetime of the measurement system. For short term measurements (up to some weeks) cyanoacrylate glue is appropriate, for long lasting installation epoxy glue is required. Usually epoxy glue requires high temperature curing (at about 80-100 °C). The preparation of the surface where the strain gauge is to be glued is of the utmost importance. The surface must be smoothed (e.g. with very fine sand paper), deoiled with solvents, the solvent traces must then be removed and the strain gauge must be glued immediately after this to avoid oxidation or pollution of the prepared area. If these steps are not followed the strain gauge binding to the surface may be unreliable and unpredictable measurement errors may be generated.

Strain gauge based technology is used commonly in the manufacture of pressure sensors. The gauges used in pressure sensors themselves are commonly made from silicon, polysilicon, metal film, thick film, and bonded foil.

Variations in temperature

Variations in temperature will cause a multitude of effects. The object will change in size by thermal expansion, which will be detected as a strain by the gauge. Resistance of the gauge will change, and resistance of the connecting wires will change.

Most strain gauges are made from a constantan alloy.[3] Various constantan alloys and Karma alloys have been designed so that the temperature effects on the resistance of the strain gauge itself largely cancel out the resistance change of the gauge due to the thermal expansion of the object under test. Because different materials have different amounts of thermal expansion, self-temperature compensation (STC) requires selecting a particular alloy matched to the material of the object under test.

Strain gauges that are not self-temperature-compensated (such as isoelastic alloy) can be temperature compensated by use of the dummy gauge technique. A dummy gauge (identical to the active strain gauge) is installed on an unstrained sample of the same material as the test specimen. The sample with the dummy gauge is placed in thermal contact with the test specimen, adjacent to the active gauge. The dummy gauge is wired into a Wheatstone bridge on an adjacent arm to the active gauge so that the temperature effects on the active and dummy gauges cancel each other.[4] (Murphy's law was originally coined in response to a set of gauges being incorrectly wired into a Wheatstone bridge.[5])

Every material reacts when it heats up or when it cools down. This will cause strain gauges to register a deformation in the material which will make it change signal. To prevent this from happening strain gauges are made so they will compensate this change due to temperature. Dependent on the material of the surface where the strain gauge is assembled on, a different expansion can be measured.

Temperature effects on the lead wires can be cancelled by using a "3-wire bridge" or a "4-wire ohm circuit"[6] (also called a "4-wire Kelvin connection").

In any case it is a good engineering practice to keep the Wheatstone bridge voltage drive low enough to avoid the self heating of the strain gauge. The self heating of the strain gauge depends on its mechanical characteristic (large strain gauges are less prone to self heating). Low voltage drive levels of the bridge reduce the sensitivity of the overall system.

Errors and compensations

- Zero Offset - If the impedance of the four gauge arms are not exactly the same after bonding the gauge to the force collector, there will be a zero offset which can be compensated by introducing a parallel resistor to one or more of the gauge arms.

- Temperature coefficient of gauge factor (TCGF) is the change of sensitivity of the device to strain with change in temperature. This is generally compensated for by the introduction of a fixed resistance in the input leg, whereby the effective supplied voltage will decrease with a temperature increase, compensating for the increase in sensitivity with the temperature increase. This is known as modulus compensation in transducer circuits. As the temperature rises the load cell element becomes more elastic and therefore under a constant load will deform more and lead to an increase in output; but the load is still the same. The clever bit in all this is that the resistor in the bridge supply must be a temperature sensitive resistor that is matched to both the material to which the gauge is bonded and also to the gauge element material. The value of that resistor is dependent on both of those values and can be calculated. In simple terms if the output increases then the resistor value also increase thereby reducing the net voltage to the transducer. Get the resistor value right and you will see no change.

- Zero shift with temperature - If the TCGF of each gauge is not the same, there will be a zero shift with temperature. This is also caused by anomalies in the force collector. This is usually compensated for with one or more resistors strategically placed in the compensation network.

- Linearity is an error whereby the sensitivity changes across the pressure range. This is commonly a function of the force collection thickness selection for the intended pressure and the quality of the bonding.

- Hysteresis is an error of return to zero after pressure excursion.

- Repeatability - This error is sometimes tied-in with hysteresis but is across the pressure range.

- EMI induced errors - As strain gauges output voltage is in the mV range, even μV if the Wheatstone bridge voltage drive is kept low to avoid self heating of the element, special care must be taken in output signal amplification to avoid amplifying also the superimposed noise. A solution which is frequently adopted is to use "carrier frequency" amplifiers which convert the voltage variation into a frequency variation (as in VCOs) and have a narrow bandwidth thus reducing out of band EMI.

- Overloading – If a strain gauge is loaded beyond its design limit (measured in microstrain) its performance degrades and can not be recovered. Normally good engineering practice suggests not to stress strain gauges beyond ±3000 microstrain.

- Humidity – If the wires connecting the strain gauge to the signal conditioner are not protected against humidity, such as bare wire, corrosion can occur, leading to parasitic resistance. This can allow currents to flow between the wires and the substrate to which the strain gauge is glued, or between the two wires directly, introducing an error which competes with the current flowing through the strain gauge. For this reason, high-current, low-resistance strain gauges (120 ohm) are less prone to this type of error. To avoid this error it is sufficient to protect the strain gauges wires with insulating enamel (e.g., epoxy or polyurethane type). Strain gauges with unprotected wires may be used only in a dry laboratory environment but not in an industrial one.

In some applications, strain gauges add mass and damping to the vibration profiles of the hardware they are intended to measure. In the turbomachinery industry, one used alternative to strain gauge technology in the measurement of vibrations on rotating hardware is the non-intrusive stress measurement system, which allows measurement of blade vibrations without any blade or disc-mounted hardware...

Geometries of strain gauges

The following different kind of strain gauges are available in the market:

- Linear strain gauges

- Membrane Rosette strain gauges

- Double linear strain gauges

- Full bridge strain gauges

- Shear strain gauges

- Half bridge strain gauges

- Column strain gauges

- 45°-Rosette (3 measuring directions)

- 90°-Rosette (2 measuring directions).

Other types

For measurements of small strain, semiconductor strain gauges, so called piezoresistors, are often preferred over foil gauges. A semiconductor gauge usually has a larger gauge factor than a foil gauge. Semiconductor gauges tend to be more expensive, more sensitive to temperature changes, and are more fragile than foil gauges.

Nanoparticle-based strain gauges emerge as a new promising technology. These resistive sensors whose active area is made by an assembly of conductive nanoparticles, such as gold or carbon, combine a high gauge factor, a large deformation range and a small electrical consumption due to their high impedance.

In biological measurements, especially blood flow and tissue swelling, a variant called mercury-in-rubber strain gauge is used. This kind of strain gauge consists of a small amount of liquid mercury enclosed in a small rubber tube, which is applied around e.g., a toe or leg. Swelling of the body part results in stretching of the tube, making it both longer and thinner, which increases electrical resistance.

Fiber optic sensing can be employed to measure strain along an optical fiber. Measurements can be distributed along the fiber, or taken at predetermined points on the fiber. The 2010 America's Cup boats Alinghi 5 and USA-17 both employ embedded sensors of this type.[7]

_from_LIMESS.gif)

Other optical measuring techniques can be used to measure strains like electronic speckle pattern interferometry or digital image correlation.

Microscale strain gauges are widely used in microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) to measure strains such as those induced by force, acceleration, pressure or sound.[8] As example, airbags in cars are often triggered with MEMS accelerometers. As alternative to piezo-resistant strain gauges, integrated optical ring resonators may be used to measure strain in microoptoelectromechanical systems (MOEMS).[9]

Capacitive strain gauges use a variable capacitor to indicate the level of mechanical deformation.

Vibrating wire strain gauges are used in geotechnical and civil engineering applications. The gauge consists of a vibrating, tensioned wire. The strain is calculated by measuring the resonant frequency of the wire (an increase in tension increases the resonant frequency).

Quartz crystal strain gauges are also used in geotechnical applications. A pressure sensor, a resonant quartz crystal strain gauge with a bourdon tube force collector is the critical sensor of DART.[10] DART detects tsunami waves from the bottom of the open ocean. It has a pressure resolution of approximately 1mm of water when measuring pressure at a depth of several kilometers.[11]

Non-contact strain measurements

Strain can also be measured using digital image correlation (DIC). With this technique one or two cameras are used in conjunction with a DIC software to track features on the surface of components to detect small motion. The full strain map of the tested sample can be calculated, providing similar display as a finite-element analysis. This technique is used in many industries to replace traditional strain gauges or other sensors like extensometers, string pots, LVDT, accelerometers.[12].. The accuracy of commercially available DIC software typically ranges around 1/100 to 1/30 of a pixels for displacements measurements which result in strain sensitivity between 20 and 100 μm/m.[13] The DIC technique allows to quickly measure shape, displacements and strain non-contact, avoiding some issues of traditional contacting methods, especially with impacts, high strain, high-temperature or high cycle fatigue testing.[14]

See also

References

- Strain Gage: Materials

- Strain Gage: Sensitivity

- Constantan Alloy: Strain Gauge Selection

- Shull, Larry C., "Basic Circuits", Hannah, R.L. and Reed, S.E. (Eds.) (1992).Strain Gage Users' Manual, p. 122. Society for Experimental Mechanics. ISBN 0-912053-36-4.

- Spark, N. (2006). A History of Murphy's Law. Periscope Film. ISBN 978-0-9786388-9-4

- The Strain Gage

- Fountain, Henry (2010-02-08). "America's Cup Rivals Race with the Wind at Their Wings". The New York Times.

- Bryzek, J.; Roundy, S.; Bircumshaw, B.; Chung, C.; Castellino, K.; Stetter, J.R.; Vestel, M. (10 April 2006). "Marvelous MEMS". IEEE Circuits and Devices Magazine. 22 (2): 8–28. doi:10.1109/MCD.2006.1615241.

- Westerveld, W.J.; Leinders, S.M.; Muilwijk, P.M.; Pozo, J.; van den Dool, T.C.; Verweij, M.D.; Yousefi, M.; Urbach, H.P. (10 January 2014). "Characterization of Integrated Optical Strain Sensors Based on Silicon Waveguides". IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics. 20 (4): 101–110. doi:10.1109/JSTQE.2013.2289992.

- Milburn, Hugh. "The NOAA DART II Description and Disclosure" (PDF). noaa.gov. NOAA, U.S. Government. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Eble, M. C.; Gonzalez, F. I. "Deep-Ocean Bottom Pressure Measurements in the Northeast Pacific" (PDF). noaa.gov. NOAA, U.S. Government. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Carr, Jennifer; Baqersad, Javad; Niezrecki, Christopher; Avitabile, Peter; Slattery, Micheal (2012), "Dynamic Stress–Strain on Turbine Blades Using Digital Image Correlation Techniques Part 2: Dynamic Measurements", Topics in Experimental Dynamics Substructuring and Wind Turbine Dynamics, Volume 2, Springer New York, pp. 221–226, doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-2422-2_21, ISBN 9781461424215

- Carr, Jennifer; Baqersad, Javad; Niezrecki, Christopher; Avitabile, Peter; Slattery, Micheal (2012), "Dynamic Stress–Strain on Turbine Blade Using Digital Image Correlation Techniques Part 1: Static Load and Calibration", Topics in Experimental Dynamics Substructuring and Wind Turbine Dynamics, Volume 2, Springer New York, pp. 215–220, doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-2422-2_20, ISBN 9781461424215

- Littell, Justin D. (2011), "Large Field Photogrammetry Techniques in Aircraft and Spacecraft Impact Testing", Dynamic Behavior of Materials, Volume 1, Conference Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Mechanics Series, Springer New York, pp. 55–67, doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-8228-5_9, hdl:2060/20100024230, ISBN 9781441982278