Streptococcus equinus

Streptococcus equinus is a Gram-positive, nonhemolytic, nonpathogenic, lactic acid bacterium of the genus Streptococcus.[5] It is the principal Streptococcus found in the alimentary canal of a horse,[6] and makes up the majority of the bacterial flora in horse feces.[7] S. equinus is seldom found in humans.[8] Equivalence with Streptococcus bovis has been contested.[4]

| Streptococcus equinus | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Firmicutes |

| Class: | Bacilli |

| Order: | Lactobacillales |

| Family: | Streptococcaceae |

| Genus: | Streptococcus |

| Species: | S. equinus |

| Binomial name | |

| Streptococcus equinus Andrewes FW, Horder TJ 1906 | |

| Synonyms[1][2][3][4] | |

| |

History

S. equinus, which is always abundant in the feces of horses, was first isolated from the air in 1906 by Andrewes and Horder due to the presence of dried horse manure, common in most cities at the time.[9]

In 1910, Winslow and Palmer verified the findings of Andrewes and Horder and reported further findings in both cattle and human feces.[10]

Phylogeny

After the bacterium was discovered in 1906, the term Streptococcus equinus became a convenient “wastebasket” into which nonhemolytic streptococci that do not ferment lactose and mannitol were categorized.[10] The classification of all streptococci that fail to ferment lactose into one large category has made the classification of S. equinus very difficult.

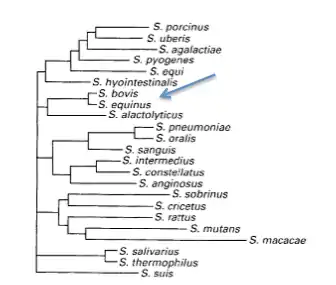

However, as shown to the left, it is known that S. equinus, a nonenterococcal, group D streptococcus, is most closely related to the species S. bovis.[7] In 2003, S. bovis and S. equinus were found to have a 99% 16S rRNA sequence similarity.[4] While particularly similar in phylogeny they differ in biochemical reactions and physiological characteristics.[4]

The taxonomy of the organisms designated as S. bovis and S. equinus has a very complex history. S. equinus and S. bovis were reported to be synonyms by Farrow et al. in 1984, but were listed as separate species in Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology in 1986.[12] Recently, the situation has become more complex by the description of two novel species for strains originally identified as S. bovis as actually S. caprinus, and S. gallolyticus.[12] The taxonomy of S. equinus has yet to be fully resolved.[13]

Characteristics

A prominent characteristic of S. equinus is its inability to ferment lactose and mannitol.[9] Moreover, it is nonhemolytic and not known to be pathogenic for animals.

Morphology

Generally, it appears as short chains of spherical or ovoid cells. These chains are somewhat longer in broth cultures than milk. Some cultures form extremely long chains in broth.[10]

Temperature of growth

S. equinus has a high minimum temperature of growth, evidenced by little or no growth in gelatin cultures at temperatures lower than 21 °C.[9][10] No growth occurs at 10 or 15 °C, and growth is very slow at 21 °C.[10] The maximum temperature of growth takes place at 45 °C, and 47 °C where growth seldom occurs.[10] No growth occurs at 48 °C.[10]

Growth medium

It does not grow well in nor can it coagulate milk.[9][10] However, it has a high fermentative power in glucose broth.[10] The organism grows with vigor in glucose-peptone-litmus milk.[10]

Thermal resistance

It has a higher resistance to temperature than that possessed by pathogenic streptococci, but substantially lower than that of thermoduric streptococci.

Most of the other properties of S. equinus have not yet been determined.

Clinical significance

S. equinus is one of the rare Gram-positive bacteria that may cause bacteremia and endocarditis in humans, but infection with this organism is very rare in humans.[14]

Rare incidences

Among the rare published cases of S. equinus reported are: infective endocarditis,[15] and peritonitis.[16]

In 1993, a case was reported of a farmer with documented aortic valve disease who developed bacterial endocarditis due to S. equinus.[15] The case report also noted that S. equinus is a rare pathogen in man and its acquisition may be related to the subject’s occupation.[15]

In 1998, a case of S. equinus peritonitis in a patient on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) was reported.[16] This case reported that S. equinus is a rare but easily treatable cause of peritonitis in CAPD patients.[16]

In 2000, a woman with no underlying cardiac abnormalities developed S. equinus endocarditis.[17] However, the patient also had pulmonary histiocytosis X.[17] While this may have been a coincidence, such patients have many abnormalities of the immune system including imbalance of the immunoregulatory cell system and a decreased production of natural antibodies.[17] Such abnormalities can predispose the patients with histiocytosis X to the development of bacterial infections, and a similar mechanism may have taken place in this patient.[17]

Overall, while this organism has been isolated from the human intestine, currently it has not been reported to cause endocarditis in patients without history of cardiac disease or another underlying condition.[8]

Future studies

To obtain a definitive discrimination between S. equinus and S. bovis, extensive further studies are required. Additional DNA-DNA hybridization studies or genomic and proteomic comparison experiments of the two species could lead to more definitive results.[18] Also, further studies using new techniques such as MALDI-TOF may also be effective.[18]

References

- POYART (C.), QUESNE (G.) and TRIEU-CUOT (P.): Taxonomic dissection of the Streptococcus bovis group by analysis of manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase gene (sodA) sequences: reclassification of 'Streptococcus infantarius subsp. coli' as Streptococcus lutetiensis sp. nov. and of Streptococcus bovis biotype II.2 as Streptococcus pasteurianus sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., 2002, 52, 1247-1255.

- FARROW (J.A.E.), KRUZE (J.), PHILLIPS (B.A.), BRAMLEY (A.J.) and COLLINS (M.D.): Taxonomic studies on Streptococcus bovis and Streptococcus equinus: description of Streptococcus alactolyticus sp. nov. and Streptococcus saccharolyticus sp. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol., 1984, 5, 467-482.

- WHILEY (R.A.) and KILIAN (M.): International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes Subcommittee on the taxonomy of staphylococci and streptococci. Minutes of the closed meeting, 31 July 2002, Paris, France. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., 2003, 53, 915-917. Minutes of the closed meeting, 31 July 2002, Paris, France in IJSEM Online

- Schlegel, L.; Grimont, F; Ageron, E; Grimont, PA; Bouvet, A (2003). "Reappraisal of the taxonomy of the Streptococcus bovis/Streptococcus equinus complex and related species: Description of Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. Gallolyticus subsp. Nov., S. Gallolyticus subsp. Macedonicus subsp. Nov. And S. Gallolyticus subsp. Pasteurianus subsp. Nov". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 53 (3): 631–45. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02361-0. PMID 12807180.

- Wood JB, Holzapfel WHN (1995). The Genera of Lactic Acid Bacteria. pp. 431–4. ISBN 978-0-7514-0215-5.

- Fuller R, Newland LG (July 1963). "The serological grouping of three strains of Streptococcus equinus". J. Gen. Microbiol. 31 (3): 431–4. doi:10.1099/00221287-31-3-431. PMID 13960231.

- Boone R, Garrity G, Castenholz R, Brenner D, Krieg N, Staley J (1991). Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Williams & Wilkins. p. 678. ISBN 978-0-387-68489-5.

- Noble CJ. (1978). "Carriage of group D streptococci in the human bowel". J Clin Pathol. 31 (12): 1182–1186. doi:10.1136/jcp.31.12.1182. PMC 1145528. PMID 107199.

- Hagan WA (1988). Hagan and Bruner's Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of Domestic Animals. p. 195.

- Hodge HM, Sherman JM (March 1937). "Streptococcus equinus". J Bacteriol. 33 (3): 283–289. doi:10.1128/JB.33.3.283-289.1937. PMC 545391. PMID 16559995.

- Logan, N (July 2009). Bacterial Systematics. p. 194. ISBN 9781444313932.

- Devriese L, Vandamme P, Pot B, Vanrobaeys M, Kersters K, Haesebrouck F (Dec 1998). "Differentiation between Streptococcus gallolyticus Strains of Human Clinical and Veterinary Origins and Streptococcus bovis Strains from the Intestinal Tracts of Ruminants". J. Clin. Microbiol. 36 (12): 3520–3. doi:10.1128/JCM.36.12.3520-3523.1998. PMC 105232. PMID 9817865.

- Deibel RH (Sep 1964). "The Group D Streptococci". Bacteriol Rev. 28 (3): 330–366. doi:10.1128/MMBR.28.3.330-366.1964. PMC 441228. PMID 14220658.

- Wallace S (September 2005). "Group D non-enteroccal streptococcus". Johns Hopkins.

- Elliott PM, Williams H, Brooks IAB (1993). "A case of infective endocarditis in a farmer caused by Streptococcus equinus". European Heart Journal. 14 (9): 1292–1293. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/14.9.1292. PMID 8223744.

- Tuncer, M; Ozcan, S; Vural, T; Sarikaya, M; Süleymanlar, G; Yakupoglu, G; Ersoy, FF (1998). "Streptococcus equinus peritonitis in a CAPD patient". Peritoneal Dialysis International. 18 (6): 654. doi:10.1177/089686089801800617. PMID 9932668.

- Sechi LA, Ciani R (1999). "Streptococcus equinus endocarditis in a patient with pulmonary histiocytosis X". Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 31 (6): 598–600. doi:10.1080/00365549950164526. PMID 10680994.

- Hinse T, Vollmer M, Erhard M, Welker ERB, Moore K, Kleesiek J (Jan 2011). "Differentiation of species of the Streptococcus bovis/equinus-complex by MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry in comparison to sodA sequence analyses". Dreier Syst Appl Microbiol. 34 (1): 52–57. doi:10.1016/j.syapm.2010.11.010. PMID 21247715.