Sudeley Castle

Sudeley Castle is a Grade I listed[1] Castle located in the Cotswolds, near to the medieval market town of Winchcombe, Gloucestershire. The castle has 10 notable gardens covering some 15 acres within a 1,200 acre estate nestled within the Cotswold hills.

| Sudeley Castle | |

|---|---|

| Winchcombe, Gloucestershire in England | |

Aerial view of Sudeley Castle | |

| Coordinates | 51°56′50″N 1°57′22″W |

| Type | Visitor Attraction, Wedding Venue and Private Residence |

| Area | 1,200 acres |

| Site information | |

| Owner |

|

| Open to the public | Seasonally |

| Status | Intact |

| Website | www |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1443 on the site of a previous fortified manor house |

| Built by |

|

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Sudeley Castle |

| Designated | 4 July 1960 |

| Reference no. | 1154791 |

| Official name | Sudeley Castle |

| Designated | 28 February 1986 |

| Reference no. | 1000784 |

| Battles/wars |

|

Building of the castle began in 1443 for Ralph Boteler; the Lord High Treasurer of England, on the site of a previous 12th century fortified manor house. It was later seized by the crown and became the property of King Edward IV and King Richard III, who built its famous banqueting hall.[2]

King Henry VIII and his then wife Anne Boleyn visited the castle in 1535;[3][4] and it later became the home and final resting place of his sixth wife, Katherine Parr, who is buried in the castle’s church, making Sudeley the only privately owned castle in England to have a Queen of England buried in its grounds.[4] Sudeley soon became the home of the Chandos Family,[3] and the castle was visited on three occasions by Queen Elizabeth I, who held a three-day party there to celebrate the defeat of the Spanish Armada.[3]

During the First English Civil War the castle was used as a military base, by King Charles I and Prince Rupert, and it was later laid to siege and slated by parliament, remaining largely in ruins for the following few centuries until its purchase in 1837 by the Dent family, who restored it to its former glory.[5]

History

11th century

Although the origins of Sudeley are lost to time, its name, a corruption of its Anglo-Saxon name Sudeleagh, meaning ‘south lying pasture or clearing in forest’[3] gives us an idea of what it was like. Sudeley can most likely thank its early rise as a royal estate to its close proximity to Winchcombe, which was during the reign of King Offa, the capital of the Kingdom of Mercia.[3] Under royal patronage, Winchcombe prospered, becoming a walled town with its own monastery, where a king and a saint are now buried.

By the turn of the 11th century, Sudeley had grown into a manor house set in a Royal deer park, given as an extravagant gift from King Ethelred the Unready to his daughter Princess Goda of England on her wedding day.[4]

Despite King William the Conqueror’s policy of depriving Saxon nobles of their estates after the Norman Conquest of 1066, the family managed to retain Sudeley, and Princess Goda’s decedents would hold Sudeley for another four centuries.[2]

12th century

During The Anarchy, John de Sudeley supported the Empress Matilda in her fight against her cousin, Stephan of Blois. His strong support of Matilda is generally accepted to have been due to his wife, Grace de Tracy being Matilda’s niece.[2]

It is believed that the first castle at Sudeley was built during this time, otherwise known as an adulterine castle. Nothing is known as to what this castle looked like; it may well have simply been the fortification of the existing manor house, or an altogether new structure.[6]

However, after the sacking of Worcester in 1139 by the forces of the Empress Matilda, under her brother Robert of Gloucester, Waleran de Beaumont, 1st Earl of Worcester retaliated, attacking and capturing both Sudeley and Tewkesbury.[2]

Although little is known of what happened to Sudeley during this attack, it seems likely that its fortifications were pulled down by the vengeful Earl of Worcester, as soon after Roger, Earl of Hereford built a replacement motte and bailey castle in Winchcombe.[7]

A few decades after the Anarchy, the Sudeley family were to step once more onto the world stage with John’s younger son, William de Tracy, participating in the murder of Thomas Beckett, Archbishop of Canterbury.[8] William was subsequently excommunicated by Pope Alexander III. He went on pilgrimage to Rome in 1171 and gained an audience with the pope, who exiled him and his fellow conspirators to Jerusalem.[2][9][8]

Construction of the current castle

By the start of the 15th century, the Sudeley name was believed to have gone extinct and the Boteler family had inherited the castle through the marriage of Joan, the sister of the last de Sudeley.[2]

Ralph Boteler is believed to have started the construction of the castle in 1443, around the same time he became Lord High Treasurer of England. Ralph rose to prominence during the Hundred Years’ War; serving in France under John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford in 1419, and was later appointed to the Regency Council of King Henry VI in 1423.[10]

Sudeley was not Ralph’s first great project, having extensively renovated the Manor on the More, the house he used when attending court, and was later described by a French Ambassador, Jean du Bellay, as more magnificent then Hampton Court.[11] Unfortunately, Ralph failed to gain royal permission to crenellate the castle, and had to seek King Henry VI's pardon.[12]

Ralph built Sudeley Castle on a double courtyard plan; with the outer courtyard being used by servants and by men-at-arms, and the inner court and its buildings reserved for the use of Ralph and his family.[10]

In 1449, Ralph’s son, Thomas Boteler, married Lady Eleanor Talbot, famed as England’s Secret Queen for her relationship with King Edward IV after the death of her husband. It was this relationship that King Richard III used to illegitimize his brother’s children and heirs, clearing the way for himself to take the crown.

Richard III

Ralph, now out of favour as a supporter of the Lancastrian cause, was in 1469 compelled to sell Sudeley and six other manors to the crown. King Edward IV bestowed Sudeley upon his brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who used it as a military base before the Battle of Tewkesbury in 1471.[2][10]

In 1478, Richard swapped Sudeley for Richmond Castle, before re-inheriting it when he acceded to the throne in 1483, when he seems to have visited both Sudeley and Kenilworth Castle on a Royal Progress.[2]

Richard is credited with having built the large banqueting hall at Sudeley.[10] This "Great Hall" was built in the latest fashions of its time, with a ground floor hall being used for meeting guests and feasting, and the upper great hall being kept specially for the king and his special guest’s use, with his own bedchambers being connected to this room.[13] When approached from the outside, the edges of the halls oriel windows are decorated with what is presumed to be the White Rose of York.

The banqueting hall now lies in partial ruins, and has been redesigned as a garden, with roses and ivy climbing the walls.

After the death of Richard at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, Sudeley, as property of the crown, transferred to King Henry VII, who in turn gifted it to his uncle Jasper Tudor.

Katherine Parr

During his reign, King Henry VIII only stayed at Sudeley once, on his 1535 Royal Progress with Queen Anne Boleyn. In the months leading up to Henry’s visit to Sudeley, he started to enact the Dissolution of the Monasteries, executing Bishop John Fisher and Sir Thomas More. Moreover, it was while he was at Sudeley that Pope Paul III and Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I started discussing his excommunication and removal.[14]

The death of Henry and the accession of King Edward VI led way for the rise of the Edward and Thomas Seymour. Henry’s will had an “unfulfilled gifts” clause that allowed for his executors to gift themselves new lands and titles, which led to Edward being declared Lord Protector of the Realm, and making his brother Baron Seymour of Sudeley.[15]

A few months after this, Thomas secretly married Henry’s widow and final wife, Queen Catherine Parr without the permission of the king, causing a small scandal.[3]

In 1548, Catherine, now pregnant, moved with her husband to Sudeley Castle, taking a considerable retinue: 120 Yeomen of the Guard and Gentlemen of the Household, plus her ladies-in-waiting and Thomas’ ward, the Lady Jane Grey.[3]

The castle was specially prepared for this move, and descriptions still exist of what Catherine’s bedchamber looked like.[16] Catherine died at Sudeley on 5th September 1548 from what was described as “childbed fever”, five days after the birth of her daughter Mary Seymour. Catherine was buried two days later at St. Mary’s Church, within the grounds of Sudeley, in what was the first Protestant funeral in English. Today, her tomb with its life-sized effigy lying under a canopy of ornately carved marble,[17] is today considered a place of pilgrimage.[3]

After Catherine’s death, her husband Thomas inherited Sudeley; he held it until he was executed for treason six months later. Catherine’s brother William Parr, 1st Marquess of Northampton, then inherited the castle, he in turn held Sudeley until 1553, when he was also accused of treason, and Sudeley was seized by the crown.[4]

Late 16th century

On 8th April 1554, John Brydges was elevated to Baron Chandos of Sudeley by Queen Mary. He had previously been Lieutenant of the Tower of London, befriending Lady Jane Grey, who he led to the scaffold, and then Princess Elizabeth, when they were in his care.[18]

His elevation almost certainly came from his assistance in the suppression of the Wyatt Rebellion.

His son Edmund Brydges heavily remodelled the castle in the 1560s and 1570s, almost completely rebuilding the outer courtyard, the part of the castle that the current family occupy, into what we see now.

Queen Elizabeth I stayed at Sudeley on three occasions during her reign, first visiting her old friend, the recently widowed Dorothy Bray, Baroness Chandos at Sudeley in 1574. Staying again during the Royal Progress of 1575, that saw Robert Dudley throw a lavish party at Kenilworth Castle in a final attempt to convince her to marry him.

Elizabeth’s most famous stay at Sudeley was in 1592, when Giles Brydges, 3rd Baron Chandos threw a three-day party for her. Giles extensively landscaped the grounds surrounding the castle in preparation for the visit, and held banquettes, plays, dances and gave extravagant gifts during her stay, even presenting his daughter, Elizabeth Brydges to the queen in the guise of Daphne.[19] The visit reputedly almost bankrupting the Brydges family.

The yearly excavations by archaeologists DigVentures since 2018 have been set on discovering more about this party, uncovering extensive Elizabethan Gardens and a possible Banqueting House.

English Civil War

Under the Chandos family, Sudeley continued to prosper and thrive, with Grey Brydges, 5th Baron Chandos gaining the title “King of the Cotswolds” for his magnificent manner and great generosity. Records show that he had been buying in expensive tapestries from abroad through William Trumbull, envoy to the Archdukes of Austria, to decorate Sudeley. Grey was an influential courtier and an avid traveller, extensively travelling Europe and taking part in the War of the Jülich Succession. He married Lady Ann Stanley, descendant of King Henry VIII’s younger sister Princess Mary Tudor, and possible heir to the throne of England.

Sudeley’s final royal occupant was to be King Charles I during the English Civil War, a war that was fought between the king and parliament.[2]

George Brydges, 6th Baron Chandos supported the royalist cause, and it was while he was supporting Prince Rupert in the siege of Cirencester in January 1643 that Sir Edward Massey, with some five hundred soldiers and two cannons attacked the castle. The small garrison soon fell and the castle was plundered; soon to be abandoned after the news that the royalist army had taken Cirencester and was turning its attention to the castle.[2]

Later that year, after Royalist army failed in the Siege of Gloucester, King Charles set up camp at Sudeley, using it as his base of operations in Gloucestershire; and then set about trying to force Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex into an open pitch battle.

The castle was to switch hands several times during the war, most famously holding out against cannon bombardment by Sir William Waller, until it was betrayed by one of its officers who let the attackers in.[2]

In 1649, after the end of the civil war, parliament ordered the slighting of the castle, a project that took some five months to complete, largely dismantling the inner courtyard and royal apartment rooms, but strangely leaving much of the outer courtyard intact. [2]

Buried in debt, George was unable to rebuild Sudeley, and he died in 1655 after years of being imprisoned in the Tower of London. On his death, the semi derelict castle was inherited by his widow, Lady Jane Savage, separating from the title Baron Chandos for the first time in over a century.

Victorian renaissance

For almost two centuries, the castle was largely left in ruins, but seemingly never becoming full abandoned.

Sudeley was owned by the Pitt Family, descendants of Lady Jane Savage’s second marriage, who were elevated to a peerage in 1776 as Baron Rivers.

During the 18th century, they rented Sudeley out to tenants, most notably the Lucas family, members of the local gentry. Joseph Lucas entertained King George III on his visit to the castle in 1788, with Mrs Cox the housekeeper saving the king’s life, catching him after he fell down the Octagon Tower.[2] The Lucas family were also involved in the rediscovery of Queen Catherine Parr’s tomb in 1782, her corpse was found to be “entire and uncorrupted”.[2]

In 1837 Sudeley Castle was purchased by brothers John and William Dent of Worcester, wealthy glove manufacturers, whose father had founded Dents Gloves in 1777.[15]

By this time, the castle was in bad shape: one of the previous tenants, John Attwood, had turned the castle into a public house “The Castle Arms”, and treated it as a quarry, breaking it up and selling off the stone, timber and lead.[2]

The Dent’s restoration of the castle was quite sensitive, deciding to not entirely rebuild the castle, rather leaving part of it as picturesque ruins, giving the castle much of its character still seen today. By 1840, the castle was habitable again, and the brothers set about filling the castle with art and antiques, buying up a considerable part of Horace Walpole’s collection during the Strawberry Hill House Sale of 1842, an auction that lasted 32 days.[5]

In 1855 the castle was inherited by the Dent Brother’s nephew, John Croucher Dent, and his wife, Emma, of the wealthy silk manufacturer family, the Brocklehursts of Macclesfield, who set about improving the castle and adding to its collections.[5]

Emma entertained on a vast scale, throwing costume balls and soirees, often hosting more than 2,000 guests a year; she was also a voracious letter writer, a number of which survive in the castle collection, including ones from Florence Nightingale.[20]

World War II

By the start of the Second World War, Sudeley was in straightened circumstances, having suffered from the huge death duties that were levied on it upon the death of Henry Dent-Brocklehurst in 1932, forcing the family to sell off much of the land the castle relied upon for its upkeep.[4]

During the war the castle was used as storage by the Tate Gallery as they moved their art out of London in an attempt to keep it safe during the Blitz.[3]

Camp 37 was located where the visitor’s car park is today, a prisoner of war camp for captured Italian and German Soldiers. The PoWs worked on local farms throughout the duration of the war until it was closed down on 20th January 1948.

Willy Reuter, who had been a German PoW at Sudeley Castle recounted:

- “While we were in this camp we had to work on several farms. On a Sunday bike tour I met Beryl Meese in Broadway. She lived in Redditch, Worcestershire (52 Sillins Avenue). We were good friends until my release. On a visit to England in 1998 with my wife, son and daughter-in-law, I was able to obtain Beryl’s brother’s telephone number from people who were living in Beryl’s parents’ old house. He told me that Beryl was on holiday in Canada — what a pity we missed her.” [21]

Sudeley today & current ownership

Sudeley today is the home of Elizabeth, Lady Ashcombe, her children, Henry and Molly Dent-Brocklehurst,[15] and grandchildren. Lady Ashcombe first came to Sudeley after her marriage to Mark Dent-Brocklehurst in 1962, and in the subsequent years set about preparing to open the castle up to the public, which they did to great celebration in May 1970. Ian Russell, 13th Duke of Bedford, who had been the first Duke to open his family seat, Woburn Abbey up to the public in 1955, attended the celebrations.[22][4]

Mark died in 1972, leaving Elizabeth, Lady Ashcombe to manage Sudeley on her own, and the castle had to survive its third round of heavy death duties in under fifty years.[4]

Elizabeth, Lady Ashcombe married Henry Cubitt, 4th Baron Ashcombe and uncle of Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall in 1979. They decided to keep Sudeley open to the public as a historic attraction and set about a major restoration of castle.[23]

BBC Four featured an investigation into the castle on 27 June 2007 titled Crisis At The Castle.[24] This detailed the turmoil associated with managing the castle within three sets of owners and their families.[25] Closing the castle to the general public on some weekdays meant that visitors were disheartened when embarking on their day trips, and resulted in a dramatic fall in visitor numbers in the three years leading up to the creation of the programme.

In the present, the castle is still very much a family home, opening seasonally to the public, who are given access to much of its gardens, the exhibitions, St Mary’s Church with access to Queen Katherine Parr’s tomb, and some of the private family rooms when the family are not in residence.[26]

The castle exhibitions were redesigned and relaunched in 2018 as “Royal Sudeley 1,000: Trials, Triumphs and Treasures”, and is set in the 15th Century Service Wing, covering three floors. It takes visitors through the thousand years of Sudeley’s history, highlighting important aspects of the castle’s past, and showing off the historical artefacts and pieces of artwork in the collection.[27]

The castle holds several events each year during its open season, from jousting, to excavations to circuses, light shows and festivals.

Sudeley is also used as a wedding venue. Over the years several celebrity weddings have taken place at the castle, from Elizabeth Hurley’s wedding in 2007, to Felicity Jones and Charles Guard in 2018.

Gardens and parkland

Sudeley Castle sits at the heart of a 1,200-acre estate that lies nestled among the Cotswold valleys.

The estate itself is made up of a mix of open pasture fields and woodland, and is crisscrossed by a number of public footpaths, most notably, The Cotswold Way, a 102-mile (164-km) long-distance footpath. These footpaths have connected Sudeley with other historic towns and monuments, such as Hailes Abbey, Broadway, Belas Knap and Stanway House.

The castle gardens cover some 15-acres and are available for the public to visit during the castle’s open season.

The garden is split into ten separate gardens, the centrepiece being the Queens’ Garden. The Queens’ Garden is the Victorian replanting of an original Elizabethan parterre garden that had been discovered in the same location, the large yew hedges surrounding it date back to 1860.[5]

Celebrated rosarian Jane Fearnley-Whittingstall is responsible for the current rose display in the Queens’ Garden, which is now home to over eighty different varieties of rose.[28]

Another garden at Sudeley is The Knot Garden, made up of more than 1,200 box hedges, its intricate design drew inspiration from the pattern of the dress worn by Queen Elizabeth I in “The Allegory of the Tudor Succession”, a painting that hangs in the castle.[28]

St Mary's Church, in which Katherine Parr is buried, is bordered by the White Garden, rich with peonies, clematis, roses and tulips, where Katherine and her companion, Lady Jane Grey would have entered the church for daily prayers.[29][30]

Sudeley is also home to one of the largest public collections of endangered pheasants in the world, and works closely with the World Pheasant Association. The pheasantry which has been operating at the castle for over thirsty years is part of a wider breeding program which has been set up in the hope of increasing the numbers of critically endangered birds before hopefully reintroducing them into their natural habitats.[31] [32]

Tourist attractions

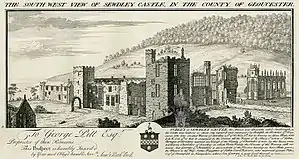

Sudeley Castle has been a tourist attraction since the early 18th century, drawing antiquarians, print makers and artists from across Britain. Some of the earliest of these being Samuel and Nathaniel Buck who visited and drew the castle in 1732 for their book Buck’s Antiquities. The castle, as a romantic ruin, welcomed King George III who visited in 1788 whilst taking the waters at Cheltenham Spa.[2]

Today, Sudeley is one of the few remaining castles left in England that is still a private residence. The Dent-Brocklehurst family remain dedicated to making the castle and gardens as accessible as possible to the general public, opening it seasonally to visitors, albeit, with the private family quarters remaining largely closed.[3][33]

Art collection

The bedrock of Sudeley’s art collection was built upon the Strawberry Hill House Sale of 1842. It was one of the most impressive auctions of its day, lasting some 32 days, selling off the art collection of Horace Walpole, son of Robert Walpole, who is generally considered the first Prime Minister of Great Britain. The collection was added to throughout the Victorian age, and then again on the inheritance part of the art collection of Victorian businessman James Morrison of Basildon Park.[5]

Not everything in the castle’s collection neatly falls into the art category, with artefacts such as a prayer book and love letter belonging to Queen Catherine Parr, weaponry, and the Bohun Book of Hours, one of only six of its kind to survive to the modern day.[34]

Not all the art collection is on display to the public, with a selection of it in the exhibitions; the rest is kept in the family private rooms. The castle does hold specialist art tours that takes small groups of visitors around the private quarters to view the art, however, these need to be booked in advance to ensure availability.[35]

This is a selection of some of the art highlighted at the castle.

- “An Allegory of Tudor Succession” Commissioned by Queen Elizabeth I for her spymaster Sir Frances Walsingham and attributed to Lucas de Heere.

- “Rise of the River Stour at Stourhead” by J. M. W. Turner. Dated to 1817 and exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1825; the Tate holds the preparatory sketches for this painting.[36]

- “A Portrait of Peter Paul Rubens” by Anthony Van Dyck.[33]

- “Flora” by Bernardino Luini, painted circ. 1515

- "Miniature of King Henry VIII" attributed to Lucus Horenbout

- "Miniature of Queen Catherine Parr" by Hans Holbein the Younger

Textile collection

Sudeley Castle’s textile collection was assembled by Emma Dent in the 19th century, it is considered one of the finest collections in the country, and was for a time, on loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Due to how delicate some of the pieces are, a select part of it is on display at the castle in the exhibitions, while the rest is kept in protective storage.

This is a selection of some of the textile highlighted at the castle.

- Louis XV Aubusson bed hangings, believed to have belonged to Queen Marie Antoinette

- The Sudeley Stumpwork Box, dating to about 1660

- A Waistcoat believed to have belonged to King Charles I

- A 16th century lace canopy, said to have been made by Queen Anne Boleyn for the christening of Queen Elizabeth I

- A fragment of cloth said to have come from the dress of Queen Catherine Parr after the rediscovery and opening of her tomb in 1782

- Early 17th century Sheldon Tapestry,[37][38][39] woven in wool, silk and metal thread, with floral designs and biblical scenes. Parallels have been drawn between it and the Filioli Tapestry that was bought by J. P. Morgan in 1911 from Knole House.[40]

Cultural references

- Sudeley is regarded by many as the model for Blandings Castle in the novels by P. G. Wodehouse.[41][15] The adaptation for BBC television of Wodehouse's Heavy Weather (1995) was filmed there.

- Scenes in series 1, episode 5 of the BBC series Father Brown were filmed at Sudeley.

- Sudeley represented Matching Priory, home of Plantagenet Palliser and his wife Lady Glencora, in the 1974 BBC classic serial The Pallisers, based on six novels by Anthony Trollope.

- The castle featured in the 1976 movie Beauty and the Beast.[42]

- The castle featured in the 1994 film Martin Chuzzlewit.[43]

- The castle featured in the 2008 mini-series Tess of the D’Urbervilles.

- The castle featured in the 2017 film adaption The White Princess, a novel by Philippa Gregory.[44]

- Sudeley provided the location for BBC Two show The Great Chelsea Garden Challenge in May 2015.

- The castle featured on BBC One show Antiques Road Trip in September 2015.

- The castle was featured on the Smithsonian Channel's show An American Aristocrat's Guide to Great Estates in June 2020.[45]

- The castle was featured in Season Two of the The Spanish Princess in 2020.

Gallery

.jpg.webp) The Queens' Garden

The Queens' Garden.jpg.webp) St. Mary's Church, Sudeley Castle

St. Mary's Church, Sudeley Castle Knot Garden

Knot Garden.jpg.webp) Catherine Parr antechamber

Catherine Parr antechamber Catherine Parr's tomb

Catherine Parr's tomb.jpg.webp) Sudeley Pheasantry

Sudeley Pheasantry.jpg.webp) Tithe Barn

Tithe Barn.jpg.webp) Northern Wing

Northern Wing

References

- "Sudeley Castle". Historic England. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- Dent, Emma (1877). Annals of WInchcombe and Sudeley. London: J. Murray. p. 318.

- Bray, Jean (2003). Sudeley Castle: A Thousand Years of English History. Sudeley Castle. p. 33.

- Hurt, Nicholas (1994). Sudeley Castle & Gardens. Wimborne, Dorset: Dovecote Press Ltd. p. 35.

- Bray, Jean (2004). The Lady of Sudeley. Stoud: Sutton Publishing Ltd. p. 66. ISBN 9780750937207.

- "Historic England research record: 327820". Heritage Gateway. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- "Historic England research record: 327810". Heritage Gateway.

- Vincent, Nicholas (2004). Becket's Murderers. Canterbury: The Friends of Canterbury Cathedral and the Trustees of the William Urry Memorial Fund. p. 20. ISBN 0951347624.

- "Thomas Becket and Henry II". BBC. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- Goodall, John (4 October 2020). "Sudeley Castle: The tumultuous tale of one of the finest castles in the Cotswolds". Country Life. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- Pollard, Albert Frederick (1978). Wolsey. Greenwood Press. p. 325. ISBN 0837179971.

- John Ashdown-Hill, "Eleanor The Secret Queen", Page 51 The History Press, 2009 ISBN 978-0-7524-5669-0

- Jones, Michael and Gwyn Meirion-Jones (1991). Les Châteaux de Bretagne. Rennes: Editions Quest-France. pp. 40–41.

- "Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 8, January-July 1535: 21-25". British History Online. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- Musson, Jeremy (2018). Secret Houses of the Cotswolds. Frances Lincoln. pp. 116–122. ISBN 978-0711239241.

- Davey, Richard (2020). The Nine Day's Queen. Frankfurt, Germany: Outlook Verlag GmbH. p. 121. ISBN 978-3-75240-094-6.

- "Sudeley Castle, Church of St. Mary". Historic England. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- "BRYDGES, Sir John (1492-1557), of Coberley, Glos". History of Parliament. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- Elizabeth Zeman Kolkovich, The Elizabethan Country House Entertainment (Cambridge, 2016), pp. 73-8.

- Dent, Emma (2011). Emma Dent's Diary. Cheltenham: Reardon Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 1873877285.

- "German PoW pal who found me 50 years later". BBC. 28 December 2005. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- Emma Kennedy (June 1, 2012). "Emma's Eccentric Britain: afternoon tea with Lady Ashcombe". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- King, Lucy. "Trials, triumphs and treasures of Sudeley Castle". Cotswold Life. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "BBC iPlayer - BBC Four". bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2019-12-14. Retrieved 2019-12-14.

- "Blogposts". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 2008-04-24. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- Sudeley History Timeline Archived October 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "Treasures from Sudeley Castle". Gloucestershire Heritage Hub. 2018. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- "Visit the Castle Gardens". Sudeley Castle & Gardens. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- "Sudeley Castle: The remarkable life, and shocking death of Katherine Parr". Tudor Travel Guide. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "Sudeley Castle". Lady Jane Grey Reference Guide. Archived from the original on 6 September 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "Critically-endangered Edwards's pheasants reared at Sudeley Castle". Sudeley Castle & Gardens. 1 November 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- "Pheasantry". Sudeley Castle & Gardens. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- "Inside the Castle". Sudeley Castle. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- "Exhibitions". Sudeley Castle & Gardens. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- "Sudeley Castle guided tours". Visit Cheltenham. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- Brown, David Blayney (2008). "The Lake and Temples at Stourhead". Tate. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- "Treasures from Sudeley Castle". Gloucestershire Heritage Hub. Archived from the original on 6 September 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "Needlework in Sudeley Castle". Cotswodl Life. Archived from the original on 6 September 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "Exhibitions". Sudeley Castle. Archived from the original on 6 September 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Turner, H. L (2011). "Transplanted: A floral tapestry-woven table carpet once at Knole, Kent". Kent Archaeology. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- N. T. P. Murphy (1981) In Search of Blandings

- "Beauty and the Beast (1976)". IMDb. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- "Martin Chuzzlewit". IMDb. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- "The White Princess". IMDb. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2020-05-27. Retrieved 2020-06-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sudeley Castle. |