Svoboda ili smart

Svoboda ili smart (Bulgarian: Свобода или смърт, 'Freedom or Death'),[2] written in pre-1945 Bulgarian orthography: "Свобода или смърть"[3] and before 1899: "Свобода или смъртъ", was a revolutionary slogan used during the national-liberation struggles by the Bulgarian revolutionaries, called comitadjis.[4] The slogan was in use during the second half of the 19th and the first half of the 20th centuries.

.jpg.webp)

History

For the first time, the slogan appeared in Georgi Rakovski's poem "Горски пътник", written in 1854 and issued in 1857. The plot of this poem concerns a Bulgarian who recruits a rebel cheta to mutiny against the Turks. He most likely accepted and transliterated the slogan Eleftheria i thanatos from the Greek liberation struggles, which was a national motto of Greece. Rakovski summoned his fellow countrymen to go to the battle fields under the banners of the Bulgarian lion. The flag with the lion was provided in 1858, when he stipulated that the national flag will have on its front side a lion depicted and the inscription "Svoboda ili smart" and on its reverse side a Christian cross and the inscription "God with us, forward!".[5] It was used for the first time during the 1860s from the Bulgarian Legions in Serbia. Then Georgi Rakovski ordered a flag and a seal with the inscriptions "Свобода или смърть".[6] Bulgarian committees used the same slogan on their flags during the April uprising of 1876. Ivan Vazov wrote the poem "Свобода или смърть" in the same year. During the Kresna–Razlog uprising in 1878 there was a banner with such inscription, prepared by the Unity Committee.[7] During the Bulgarian unification of 1885, flags with this inscriptions were also waived by members of the Bulgarian Secret Central Revolutionary Committee.[8] The pro-Bulgarian Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization, established in 1893 in the Ottoman Empire, also accepted the same slogan.[9][10] The motto was also used by the Sofia based Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committee between 1894 and 1904. During the Balkan Wars the volunteers from the Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps in Bulgarian army, had several flags with this motto. In interwar Greece and Yugoslavia the motto was used by the pro-Bulgarian Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation and Internal Thracian Revolutionary Organisation. In interwar Romania, it was used by the pro-Bulgarian Internal Dobrujan Revolutionary Organisation in Southern Dobruja. During the Second World War this motto was utilized from the pro-Bulgarian Ohrana active in Northern Greece. The uniforms of the Ohranists were supplied by the Italians and were resplendent with shoulder patches bearing the inscription "Italo-Bulgarian Committee: Freedom or Death".[11] It was also utilized as title of several newspapers of these organizations.

Post-WWII references

After 1944 in Communist Yugoslavia a distinct Macedonian language was codified and separate Macedonian nation was recognized.[12] Macedonian became a “first” official language in the newly proclaimed SR Macedonia, where Serbo-Croatian was declared as “second” language, while Bulgarian was prohibited.[13] The Bulgarian spelling "Свобода или смърть" utilized by the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization,[14] was transformed into Macedonian as "Слобода или смрт", and became identical to the motto of the Serbian Chetniks.[15] All documents written by Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionaries in standard Bulgarian were translated into Macedonian, and presented as originals.[16][17] Thus, generations of students were taught in pseudo-history.[18] This story has continued in present-day North Macedonia where the motto "Свобода или смърть" is described as written originally in Macedonian. That caused protests from Bulgarian side.[19][20] Curiosily, today as part of the controversial nation-building project Skopje 2014,[21] street lamps are mounted in the center of the city, on which the Bulgarian inscription "Свобода или смърть" is readable.[22]

See also

Artifacts with the motto

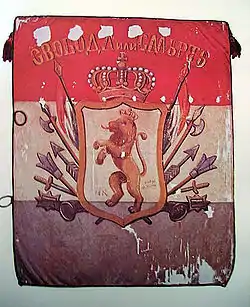

Flag of the Bulgarian legion from 1862.

Flag of the Bulgarian legion from 1862. Flag of Filip Totyu's cheta from 1867.

Flag of Filip Totyu's cheta from 1867. Flag of the Stara Zagora revolt from 1875.

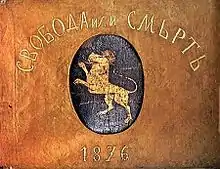

Flag of the Stara Zagora revolt from 1875. The flag of the April Uprising from 1876, sewn by Rayna Knyaginya.

The flag of the April Uprising from 1876, sewn by Rayna Knyaginya. Tarnovo cheta's Bulgarian Unification flag from 1885.

Tarnovo cheta's Bulgarian Unification flag from 1885. Gorna Dzhumaya rebellion flag from 1895.

Gorna Dzhumaya rebellion flag from 1895. The banner of the insurgents from Ohrid from 1903.

The banner of the insurgents from Ohrid from 1903. The banner of the insurgents from Smoljan from 1903.

The banner of the insurgents from Smoljan from 1903. The banner of the insurgents from Struga from 1903.

The banner of the insurgents from Struga from 1903. The banner of the insurgents from Kastoria from 1903.

The banner of the insurgents from Kastoria from 1903. IMRO merit badge from ca. 1925.

IMRO merit badge from ca. 1925. The stamp of Tane Nikolov, leader of ITRO

The stamp of Tane Nikolov, leader of ITRO The newspaper of IMRO "Liberty of Death", issue from 1930.

The newspaper of IMRO "Liberty of Death", issue from 1930. IDRO stamp from 1930s.

IDRO stamp from 1930s.

References

- Андрей Цветков, Георги Стойков Раковски: 1821-1871: биографичен очерк, Народна просвета, 1971, София, стр. 52-53.

- Karen-Margrethe Simonsen, Jakob Stougaard-Nielsen as ed., World Literature, World Culture, ISD LLC, 2008, ISBN 8779349900, p. 95.

- Ernest A. Scatton, Grammar of Modern Bulgarian, Slavica Pub, 1984, ISBN 0893571237, p. 121.

- The word komitadji is Turkish, meaning literally "committee man". It came to be used for the guerilla bands which, subsidized by the governments of the Christian Balkan states, especially of Bulgaria. "The Making of a New Europe: R.W. Seton-Watson and the Last Years of Austria-Hungary", Hugh Seton-Watson, Christopher Seton-Watson, Methuen, 1981, ISBN 0416747302, p. 71.

- Известия на държавните архиви, том 58, Наука и изкуство, София, 1989, стр. 57.

- Veselin Traĭkov, G. Mukherjee, Georgi Stoikov Rakovski, a Great Son of Bulgaria and a Great Friend of India, Northern Book Centre, ISBN 8185119287, p. 127.

- Дойно Дойнов, Кресненско-Разложкото въстание, 1878-1879, (Издателство на Българската Академия на науките. София, 1979) стр. 51.

- Исторически преглед, том 16, Българско историческо дружество, Институт за история (Българска академия на науките), 1960, стр. 16.

- The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization was inspired by Bulgarian freedom fighters, and adopted the "Liberty or Death" slogan beloved of earlier Bulgarian insurgents, IMRO revolutionaries clearly saw themselves as the inheritors of Bulgarian revolutionary traditions and identified as Bulgarians. Jonathan Bousfield, Dan Richardson, Bulgaria, Rough Guides, 2002, ISBN 1858288827, p. 450.

- IMRO group modeled itself after the revolutionary organizations of Vasil Levski and other noted Bulgarian revolutionaries like Hristo Botev and Georgi Benkovski, each of whom was a leader during the earlier Bulgarian revolutionary movement. Around this time ca. 1894, a seal was struck for use by the Organization leadership; it was inscribed with the phrase "Freedom or Death" (Svoboda ili smurt). Duncan M. Perry, The Politics of Terror: The Macedonian Liberation Movements, 1893-1903, Duke University Press, 1988, ISBN 0822308134, pp. 39-40.

- Даскалов, Г. Участта на българите в Егейска Македония 1936-1946. Македонски научен институт, София, 1999, стр. 432.

- Yugoslav Communists recognized the existence of a Macedonian nationality during WWII to quiet fears of the Macedonian population that a communist Yugoslavia would continue to follow the former Yugoslav policy of forced Serbianization. Hence, for them to recognize the inhabitants of Macedonia as Bulgarians would be tantamount to admitting that they should be part of the Bulgarian state. For that the Yugoslav Communists were most anxious to mold Macedonian history to fit their conception of Macedonian consciousness. The treatment of Macedonian history in Communist Yugoslavia had the same primary goal as the creation of the Macedonian language: to de-Bulgarize the Macedonian Slavs and to create a separate national consciousness that would inspire identification with Yugoslavia. For more see: Stephen E. Palmer, Robert R. King, Yugoslav communism and the Macedonian question, Archon Books, 1971, ISBN 0208008217, Chapter 9: The encouragement of Macedonian culture.

- The Macedonian partisans established a commission to create an “official” Macedonian literary language (1945), which became the Macedonian Slavs' legal “first” language (with Serbo-Croatian a recognized “second” and Bulgarian officially proscribed). D. Hupchick, The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism, Springer, 2002, ISBN 0312299133, p. 430.

- The "Adrianopolitan" part of the organization's name indicates that its agenda concerned not only Macedonia but also Thrace — a region whose Bulgarian population is by no means claimed by Macedonian nationalists today. In fact, as the organization's initial name ("Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees") shows, it had a Bulgarian national character: the revolutionary leaders were quite often teachers from the Bulgarian schools in Macedonia. This was the case of founders of the organization... Their organization was popularly seen in the local context as "the Bulgarian committee(s). Tchavdar Marinov, Famous Macedonia, the Land of Alexander: Macedonian identity at the crossroads of Greek, Bulgarian and Serbian nationalism in Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies with Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov as ed., BRILL, 2013, ISBN 900425076X, pp. 273-330.

- Today some historians and linguists in the Republic of Macedonia, have described the process of codifying the Macedonian language after WWII as 'Serbianization'. For more see: Tchavdar Marinov, Historiographical Revisionism and Re-Articulation of Memory in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Fonds d'analyse des sociétés politiques, May 2010, Issue 25, p. 7.

- The Macedonian Revolutionary Organization used the Bulgarian standard language in all its programmatic statements and its correspondence was solely in the Bulgarian language, nearly all of its leaders were Bulgarian teachers or Bulgarian officers, and received financial and military help from Bulgaria. After 1944 all the literature of Macedonian writers, memoirs of Macedonian leaders, and important documents had to be translated from Bulgarian into the newly invented Macedonian. For more see: Bernard A. Cook ed., Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia, Volume 2, Taylor & Francis, 2001, ISBN 0815340583, p. 808.

- "The obviously plagiarized historical argument of the Macedonian nationalists for a separate Macedonian ethnicity could be supported only by linguistic reality, and that worked against them until the 1940s. Until a modern Macedonian literary language was mandated by the communist-led partisan movement from Macedonia in 1944, most outside observers and linguists agreed with the Bulgarians in considering the vernacular spoken by the Macedonian Slavs as a western dialect of Bulgarian". Dennis P. Hupchick, Conflict and Chaos in Eastern Europe, Palgrave Macmillan, 1995, ISBN 0312121164, p. 143.

- In one respect, however, Macedonian nationalism threw up a problem which the Communist Party could not ignore: the question of the status of the Macedonian language. If, as Dr. Johnson remarked, languages are the pedigrees of nations, then the Slav inhabitants of Macedonia were by any reasonable linguistic criteria part of the Bulgarian nation... The construction and dissemination of a distinctive Macedonian language was the medium through which a sense of Macedonian identity was to be fixed... The past was systematically falsified to conceal the fact that many prominent ‘Macedonians’ had supposed themselves to be Bulgarians, and generations of students were taught the pseudo-history of the Macedonian nation. The mass media and education were the key to this process of national acculturation, speaking to people in a language that they came to regard as their Macedonian mothertongue, even if it was perfectly understood in Sofia. For more see: Michael L. Benson, Yugoslavia: A Concise History, Edition 2, Springer, 2003, ISBN 1403997209, p. 89.

- България се оттегля от изложбата "Идентичност и памет през XIX век" в Белград. 10.09.2013, БНР.

- Federico Sicurella, Balkan history: testing imagination. Osservatorio Balcani Caucaso Transeuropa, 23/09/2013, Belgrade.

- Janev, G. (2015). ‘Skopje 2014’: erasing memories, building history. In M. Couroucli, & T. Marinov (Eds.), Balkan heritages: Negotiating history and culture (pp. 111-130). Taylor & Francis, 2017, ISBN 1134800754.

- „Барокни“ канделабри со натпис „Слобода или смрт“ го красат плоштадот „ВМРО“. А1ON, 28 Јан 2016.