Tajikistan

Tajikistan (/tɑːˈdʒiːkɪstɑːn/ (![]() listen), /tə-, tæ-/; Tajik: Тоҷикистон, [tɔdʒikisˈtɔn], Russian: Таджикистан, romanized: Tadzhikistan), officially the Republic of Tajikistan (Tajik: Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон, romanized: Jumhurii Tojikiston), is a landlocked country in Central Asia with an area of 143,100 km2 (55,300 sq mi)[5][6][7] and an estimated population of 9,537,645 people.[14] It is bordered by Afghanistan to the south, Uzbekistan to the west, Kyrgyzstan to the north and China to the east. The traditional homelands of the Tajik people include present-day Tajikistan as well as parts of Afghanistan and Uzbekistan.

listen), /tə-, tæ-/; Tajik: Тоҷикистон, [tɔdʒikisˈtɔn], Russian: Таджикистан, romanized: Tadzhikistan), officially the Republic of Tajikistan (Tajik: Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон, romanized: Jumhurii Tojikiston), is a landlocked country in Central Asia with an area of 143,100 km2 (55,300 sq mi)[5][6][7] and an estimated population of 9,537,645 people.[14] It is bordered by Afghanistan to the south, Uzbekistan to the west, Kyrgyzstan to the north and China to the east. The traditional homelands of the Tajik people include present-day Tajikistan as well as parts of Afghanistan and Uzbekistan.

Republic of Tajikistan | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) Location of Tajikistan (green) | |

| Capital and largest city | Dushanbe 38°33′N 68°48′E |

| Official languages | Tajiki |

| Official language of inter-ethnic communication | Russian[1] |

| Other languages | Uzbek • Kyrgyz • Shughni • Rushani • Yaghnobi • Bartangi • Sanglechi-Ishkashimi • Parya • Bukhori |

| Ethnic groups (2010[2]) | |

| Religion | |

| Demonym(s) | Tajik[4] |

| Government | Unitary dominant-party presidential constitutional secular republic |

| Emomali Rahmon | |

| Kokhir Rasulzoda | |

• Chairman of the Majlisi Milli | Rustam Emomali |

| Legislature | Supreme Assembly |

| National Assembly | |

| Assembly of Representatives | |

| Independence from Russia | |

| 27 November 1917 | |

| 27 October 1924 | |

| 5 December 1929 | |

• From the USSR | 9 September 1991 |

| 21 December 1991 | |

• Recognized | 26 December 1991 |

| 2 March 1992 | |

| 6 November 1994 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 143,100 km2 (55,300 sq mi)[5][6][7] (94th) |

• Water (%) | 1.8 |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 9,537,645[8] (96th[9]) |

• Density | 48.6/km2 (125.9/sq mi) (155th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $30.547 billion[10] (132nd) |

• Per capita | $3,354[10] (155th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $7.350 billion[10] (147th) |

• Per capita | $807[10] (164th) |

| Gini (2015) | 34[11] medium |

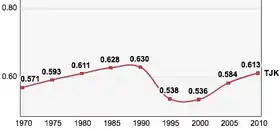

| HDI (2019) | medium · 125th |

| Currency | Somoni (TJS) |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (TJT) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +992 |

| ISO 3166 code | TJ |

| Internet TLD | .tj |

| |

The territory that now constitutes Tajikistan was previously home to several ancient cultures, including the city of Sarazm[15] of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age and was later home to kingdoms ruled by people of different faiths and cultures, including the Oxus Valley Civilisation, Andronovo Culture, Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity, Vedic religion, Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism and Islam. The area has been ruled by numerous empires and dynasties, including the Achaemenid Empire, Sasanian Empire, Hephthalite Empire, Samanid Empire and the Mongol Empire. After being ruled by the Timurid dynasty and the Khanate of Bukhara, the Timurid Renaissance flourished. The region was later conquered by the Russian Empire and subsequently by the Soviet Union. Within the Soviet Union, the country's modern borders were drawn when it was part of Uzbekistan as an autonomous republic before becoming a full-fledged Soviet republic in 1929.[16]

On 9 September 1991, Tajikistan became an independent sovereign nation when the Soviet Union disintegrated. A civil war was fought almost immediately after independence, lasting from 1992 to 1997. Since the end of the war, newly established political stability and foreign aid have allowed the country's economy to grow. The country, led by President Emomali Rahmon since 1994, has been criticised by a number of non-governmental organizations for authoritarian leadership, corruption and widespread violations of human rights, including torture, arbitrary imprisonment, lack of religious freedom and other civil liberties, and worsening political repression.[17]

Tajikistan is a presidential republic consisting of four provinces. Most of Tajikistan's population belongs to the Tajik ethnic group,[18] who speak Tajik (a dialect of Persian). Russian is used as the inter-ethnic language. While the state is constitutionally secular, Islam is practiced by 98% of the population. In the Gorno-Badakhshan oblast, despite its sparse population, there is large linguistic diversity where Rushani, Shughni, Ishkashimi, Wakhi and Tajik are some of the languages spoken. Mountains cover more than 90% of the country. It is a developing country with a transition economy that is highly dependent on remittances, aluminium and cotton production. Tajikistan is a member of the United Nations, CIS, OSCE, OIC, ECO, SCO and CSTO as well as an NATO PfP partner.

Etymology

Tajikistan means the "Land of the Tajiks". The suffix "-stan" is Persian for "place of"[19] or "country"[20] and Tajik is, most likely, the name of a pre-Islamic (before the seventh century A.D.) tribe.[21]

One of the most prominent Persian dictionary, the Amid Dictionary, gives the following explanations of the term, according to multiple sources:[22]

- Neither Arab nor Turk, he who speaks Persian, a Persian-speaking person.

- An Arab child who is bred in Persia, and thus speaks Persian.

An older dictionary, Qias Al-luqat, also defines Tajik as "one who is neither a Mongol nor a Turk".[23]

Tajikistan appeared as Tadjikistan or Tadzhikistan in English prior to 1991. This is due to a transliteration from the Russian: "Таджикистан". In Russian, there is no single letter j to represent the phoneme /ʤ/, and therefore дж, or dzh, is used. Tadzhikistan is the most common alternate spelling and is widely used in English literature derived from Russian sources.[24] "Tadjikistan" is the spelling in French and can occasionally be found in English language texts. The way of writing Tajikistan in the Perso-Arabic script is: تاجیکستان.

Even though the Library of Congress's 1997 Country Study of Tajikistan found it difficult to definitively state the origins of the word "Tajik" because the term is "embroiled in twentieth-century political disputes about whether Turkic or Iranian peoples were the original inhabitants of Central Asia."[21] most scholars concluded that contemporary Tajiks are the descendants of ancient Eastern Iranian inhabitants of Central Asia, in particular, the Sogdians and the Bactrians, and possibly other groups, with an admixture of Western Iranian Persians and non-Iranian peoples.[25][26] According to Richard Nelson Frye, a leading historian of Iranian and Central Asian history, the Persian migration to Central Asia may be considered the beginning of the modern Tajik nation, and ethnic Persians, along with some elements of East-Iranian Bactrians and Sogdians, as the main ancestors of modern Tajiks.[27] In later works, Frye expands on the complexity of the historical origins of the Tajiks. In a 1996 publication, Frye explains that many "factors must be taken into account in explaining the evolution of the peoples whose remnants are the Tajiks in Central Asia" and that "the peoples of Central Asia, whether Iranian or Turkic speaking, have one culture, one religion, one set of social values and traditions with only language separating them."[28]

Regarding Tajiks, the Encyclopædia Britannica states:

The Tajiks are the direct descendants of the Iranian peoples whose continuous presence in Central Asia and northern Afghanistan is attested from the middle of the 1st millennium BC. The ancestors of the Tajiks constituted the core of the ancient population of Khwārezm (Khorezm) and Bactria, which formed part of Transoxania (Sogdiana). Over the course of time, the eastern Iranian dialect that was used by the ancient Tajiks eventually gave way to Farsi, a western dialect spoken in Iran and Afghanistan.[29]

History

Early history

Cultures in the region have been dated back to at least the 4th millennium BCE, including the Bronze Age Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex, the Andronovo cultures and the pro-urban site of Sarazm, a UNESCO World Heritage site.[30]

The earliest recorded history of the region dates back to about 500BC when much, if not all, of modern Tajikistan was part of the Achaemenid Empire.[21] Some authors have also suggested that in the 7th and 6th century BC, parts of modern Tajikistan, including territories in the Zeravshan valley, formed part of Kambojas before it became part of the Achaemenid Empire.[31] After the region's conquest by Alexander the Great it became part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, a successor state of Alexander's empire. Northern Tajikistan (the cities of Khujand and Panjakent) was part of Sogdia, a collection of city-states which was overrun by Scythians and Yuezhi nomadic tribes around 150BC. The Silk Road passed through the region and following the expedition of Chinese explorer Zhang Qian during the reign of Wudi (141BC–87BC) commercial relations between Han China and Sogdiana flourished.[32][33] Sogdians played a major role in facilitating trade and also worked in other capacities, as farmers, carpetweavers, glassmakers, and woodcarvers.[34]

The Kushan Empire, a collection of Yuezhi tribes, took control of the region in the first century CE and ruled until the 4th century CE during which time Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and Manichaeism were all practised in the region.[35] Later the Hephthalite Empire, a collection of nomadic tribes, moved into the region and Arabs brought Islam in the early eighth century.[35] Central Asia continued in its role as a commercial crossroads, linking China, the steppes to the north, and the Islamic heartland.

It was temporarily under the control of the Tibetan empire and Chinese from 650 to 680 and then under the control of the Umayyads in 710. The Samanid Empire, 819 to 999, restored Persian control of the region and enlarged the cities of Samarkand and Bukhara (both cities are today part of Uzbekistan) which became the cultural centres of Iran and the region was known as Khorasan. The Kara-Khanid Khanate conquered Transoxania (which corresponds approximately with modern-day Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, southern Kyrgyzstan and southwest Kazakhstan) and ruled between 999 and 1211.[36][37] Their arrival in Transoxania signalled a definitive shift from Iranian to Turkic predominance in Central Asia,[38] but gradually the Kara-khanids became assimilated into the Perso-Arab Muslim culture of the region.[39]

During Genghis Khan's invasion of Khwarezmia in the early 13th century the Mongol Empire took control over nearly all of Central Asia.[40] In less than a century the Mongol Empire broke up and modern Tajikistan came under the rule of the Chagatai Khanate. Tamerlane created the Timurid dynasty and took control of the region in the 14th century.[41]

Modern Tajikistan fell under the rule of the Khanate of Bukhara during the 16th century and with the empire's collapse in the 18th century it came under the rule of both the Emirate of Bukhara and Khanate of Kokand. The Emirate of Bukhara remained intact until the 20th century but during the 19th century, for the second time in world history, a European power (the Russian Empire) began to conquer parts of the region.[42]

Russian Tajikistan

Russian Imperialism led to the Russian Empire's conquest of Central Asia during the late 19th century's Imperial Era. Between 1864 and 1885, Russia gradually took control of the entire territory of Russian Turkestan, the Tajikistan portion of which had been controlled by the Emirate of Bukhara and Khanate of Kokand. Russia was interested in gaining access to a supply of cotton and in the 1870s attempted to switch cultivation in the region from grain to cotton (a strategy later copied and expanded by the Soviets).[43] By 1885 Tajikistan's territory was either ruled by the Russian Empire or its vassal state, the Emirate of Bukhara, nevertheless Tajiks felt little Russian influence.

During the late 19th century the Jadidists established themselves as an Islamic social movement throughout the region. Although the Jadidists were pro-modernization and not necessarily anti-Russian, the Russians viewed the movement as a threat because the Russian Empire was predominately Christian.[44] Russian troops were required to restore order during uprisings against the Khanate of Kokand between 1910 and 1913. Further violence occurred in July 1916 when demonstrators attacked Russian soldiers in Khujand over the threat of forced conscription during World War I. Despite Russian troops quickly bringing Khujand back under control, clashes continued throughout the year in various locations in Tajikistan. [45]

Soviet Tajikistan

After the Russian Revolution of 1917 guerrillas throughout Central Asia, known as basmachi, waged a war against Bolshevik armies in a futile attempt to maintain independence.[40] The Bolsheviks prevailed after a four-year war, in which mosques and villages were burned down and the population heavily suppressed. Soviet authorities started a campaign of secularisation. Practising Islam, Judaism, and Christianity was discouraged and repressed, and many mosques, churches, and synagogues were closed.[46] As a consequence of the conflict and Soviet agriculture policies, Central Asia, Tajikistan included, suffered a famine that claimed many lives.[47]

In 1924, the Tajik Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was created as a part of Uzbekistan,[40] but in 1929 the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic (Tajik SSR) was made a separate constituent republic;[40] however, the predominantly ethnic Tajik cities of Samarkand and Bukhara remained in the Uzbek SSR. Between 1927 and 1934, collectivisation of agriculture and a rapid expansion of cotton production took place, especially in the southern region.[48] Soviet collectivisation policy brought violence against peasants and forced resettlement occurred throughout Tajikistan. Consequently, some peasants fought collectivisation and revived the Basmachi movement. Some small scale industrial development also occurred during this time along with the expansion of irrigation infrastructure.[48]

Two rounds of Stalin's purges (1927–1934 and 1937–1938) resulted in the expulsion of nearly 10,000 people, from all levels of the Communist Party of Tajikistan.[49] Ethnic Russians were sent in to replace those expelled and subsequently Russians dominated party positions at all levels, including the top position of first secretary.[49] Between 1926 and 1959 the proportion of Russians among Tajikistan's population grew from less than 1% to 13%.[50] Bobojon Ghafurov, First Secretary of the Communist Party of Tajikistan from 1946–1956, was the only Tajik politician of significance outside of the country during the Soviet Era.[51] He was followed in office by Tursun Uljabayev (1956–61), Jabbor Rasulov (1961–1982), and Rahmon Nabiyev (1982–1985, 1991–1992).

Tajiks began to be conscripted into the Soviet Army in 1939 and during World War II around 260,000 Tajik citizens fought against Germany, Finland and Japan. Between 60,000 (4%)[52] and 120,000 (8%)[53] of Tajikistan's 1,530,000 citizens were killed during World War II.[54] Following the war and Stalin's reign, attempts were made to further expand the agriculture and industry of Tajikistan.[51] During 1957–58 Nikita Khrushchev's Virgin Lands Campaign focused attention on Tajikistan, where living conditions, education and industry lagged behind the other Soviet Republics.[51] In the 1980s, Tajikistan had the lowest household saving rate in the USSR,[55] the lowest percentage of households in the two top per capita income groups,[56] and the lowest rate of university graduates per 1000 people.[57] By the late 1980s Tajik nationalists were calling for increased rights. Real disturbances did not occur within the republic until 1990. The following year, the Soviet Union collapsed, and Tajikistan declared its independence on 9 September 1991, a day which is now celebrated as the country's Independence Day.[58]

Gaining independence

In Soviet times, supporters of Tajikistan independence were harshly persecuted by the KGB, and most were shot and jailed for long years. After the beginning of the Perestroika era, declared by Mikhail Gorbachev throughout the USSR, supporters of the independence of the republics began to speak openly and freely. In Tajikistan SSR, the independence movement has been active since 1987. Supporters of independence were the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan, the Democratic Party of Tajikistan and the national democratic Rastokhez (Revival) Movement. On the eve of the collapse of the USSR, the population of Tajikistan SSR was divided into two camps. The first wanted independence for Tajikistan, the restoration of Tajik culture and language, the restoration of political and cultural relations with Iran and Afghanistan and other countries, and the second part of the population opposed independence, considering it the best option to remain part of the USSR. Opposed independence mainly Russian-speaking population of Tajikistan.

Since February 1990, there have been riots and strikes in Dushanbe (1990 Dushanbe riots)[40] and other cities of Tajikistan due to the difficult socio-economic situation, lack of housing, and youth unemployment. The nationalist and democratic opposition, and supporters of independence joined the strikes and began to demand the independence of the republic and democratic reforms. Islamists also began to hold strikes and demand respect for their rights and independence of the republic. The Soviet leadership introduced Internal Troops in Dushanbe to eliminate the unrest.[40]

Independence

The nation almost immediately fell into civil war that involved various factions fighting one another; these factions were often distinguished by clan loyalties.[59] More than 500,000 residents fled during this time because of persecution, increased poverty and better economic opportunities in the West or in other former Soviet republics.[60] Emomali Rahmon came to power in 1992,[40] defeating former prime minister Abdumalik Abdullajanov in a November presidential election with 58% of the vote.[61] The elections took place shortly after the end of the war, and Tajikistan was in a state of complete devastation. The estimated dead numbered over 100,000. Around 1.2 million people were refugees inside and outside of the country.[59] In 1997, a ceasefire was reached between Rahmon and opposition parties under the guidance of Gerd D. Merrem,[40] Special Representative to the Secretary General, a result widely praised as a successful United Nations peacekeeping initiative. The ceasefire guaranteed 30% of ministerial positions would go to the opposition.[62] Elections were held in 1999, though they were criticised by opposition parties and foreign observers as unfair and Rahmon was re-elected with 98% of the vote.[40] Elections in 2006 were again won by Rahmon (with 79% of the vote) and he began his third term in office. Several opposition parties boycotted the 2006 election and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) criticised it, although observers from the Commonwealth of Independent States claimed the elections were legal and transparent.[63][64] Rahmon's administration came under further criticism from the OSCE in October 2010 for its censorship and repression of the media. The OSCE claimed that the Tajik Government censored Tajik and foreign websites and instituted tax inspections on independent printing houses that led to the cessation of printing activities for a number of independent newspapers.[65]

Russian border troops were stationed along the Tajik–Afghan border until summer 2005. Since the September 11, 2001 attacks, French troops have been stationed at the Dushanbe Airport in support of air operations of NATO's International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan. United States Army and Marine Corps personnel periodically visit Tajikistan to conduct joint training missions of up to several weeks duration. The Government of India rebuilt the Ayni Air Base, a military airport located 15 km southwest of Dushanbe, at a cost of $70 million, completing the repairs in September 2010.[66] It is now the main base of the Tajikistan air force. There have been talks with Russia concerning use of the Ayni facility,[67] and Russia continues to maintain a large base on the outskirts of Dushanbe.[68]

In 2010, there were concerns among Tajik officials that Islamic militarism in the east of the country was on the rise following the escape of 25 militants from a Tajik prison in August, an ambush that killed 28 Tajik soldiers in the Rasht Valley in September,[69] and another ambush in the valley in October that killed 30 soldiers,[70] followed by fighting outside Gharm that left 3 militants dead. To date the country's Interior Ministry asserts that the central government maintains full control over the country's east, and the military operation in the Rasht Valley was concluded in November 2010.[71] However, fighting erupted again in July 2012.[72] In 2015, Russia sent more troops to Tajikistan.[73]

In May 2015, Tajikistan's national security suffered a serious setback when Colonel Gulmurod Khalimov, commander of the special-purpose police unit (OMON) of the Interior Ministry, defected to the Islamic State[40].[74]

Politics

Almost immediately after independence, Tajikistan was plunged into a civil war that saw various factions fighting one another. These factions were supported by foreign countries including Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, Uzbekistan and Russia. Russia and Iran focused on keeping peace in the warring nation to decrease the chances of U.S. or Turkish involvement. Most notably, Russia backed the pro-government faction and deployed troops from the Commonwealth of Independent States to guard the Tajikistan-Afghan border.[75] All but 25,000 of the more than 400,000 ethnic Russians, who were mostly employed in industry, fled to Russia. By 1997, the war had ended after a peace agreement between the government and the Islamist-led opposition, a central government began to take form, with peaceful elections in 1999.[76]

"Longtime observers of Tajikistan often characterize the country as profoundly averse to risk and skeptical of promises of reform, a political passivity they trace to the country’s ruinous civil war," Ilan Greenberg wrote in a news article in The New York Times just before the country's November 2006 presidential election.[77]

Tajikistan is officially a republic, and holds elections for the presidency and parliament, operating under a presidential system. It is, however, a dominant-party system, where the People's Democratic Party of Tajikistan routinely has a vast majority in Parliament. Emomali Rahmon has held the office of President of Tajikistan continuously since November 1994. The Prime Minister is Kokhir Rasulzoda, the First Deputy Prime Minister is Matlubkhon Davlatov and the two Deputy Prime Ministers are Murodali Alimardon and Ruqiya Qurbanova.

The parliamentary elections of 2005 aroused many accusations from opposition parties and international observers that President Emomali Rahmon corruptly manipulates the election process and unemployment. The most recent elections, in February 2010, saw the ruling PDPT lose four seats in Parliament, yet still maintain a comfortable majority. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe election observers said the 2010 polling "failed to meet many key OSCE commitments" and that "these elections failed on many basic democratic standards."[78][79] The government insisted that only minor violations had occurred, which would not affect the will of the Tajik people.[78][79]

_2.jpg.webp)

The presidential election held on 6 November 2006 was boycotted by "mainline" opposition parties, including the 23,000-member Islamic Renaissance Party. Four remaining opponents "all but endorsed the incumbent", Rahmon.[77] Tajikistan gave Iran its support in Iran's membership bid to join the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, after a meeting between the Tajik President and the Iranian foreign minister.[80]

Freedom of the press is ostensibly officially guaranteed by the government, but independent press outlets remain restricted, as does a substantial amount of web content.[81] According to the Institute for War & Peace Reporting, access is blocked to local and foreign websites including avesta.tj, Tjknews.com, ferghana.ru, centrasia.org and journalists are often obstructed from reporting on controversial events. In practice, no public criticism of the regime is tolerated and all direct protest is severely suppressed and does not receive coverage in the local media.[82]

In the Economist's democracy index report of 2020, Tajikistan is placed 160th, just after Saudi Arabia, as an "authoritarian regime".[83]

In July 2019, UN ambassadors of 37 countries, including Tajikistan, have signed a joint letter to the UNHRC defending China's treatment of Uyghurs in the Xinjiang region.[84]

Geography

Tajikistan is landlocked, and is the smallest nation in Central Asia by area. It lies mostly between latitudes 36° and 41° N, and longitudes 67° and 75° E. It is covered by mountains of the Pamir range, and most of the country is over 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) above sea level. The only major areas of lower land are in the north (part of the Fergana Valley), and in the southern Kofarnihon and Vakhsh river valleys, which form the Amu Darya. Dushanbe is located on the southern slopes above the Kofarnihon valley.

| Mountain | Height | Location | ||

| Ismoil Somoni Peak (highest) | 7,495 m | 24,590 ft | North-western edge of Gorno-Badakhshan (GBAO), south of the Kyrgyz border | |

| Ibn Sina Peak (Lenin Peak) | 7,134 m | 23,537 ft | Northern border in the Trans-Alay Range, north-east of Ismoil Somoni Peak | |

| Peak Korzhenevskaya | 7,105 m | 23,310 ft | North of Ismoil Somoni Peak, on the south bank of Muksu River | |

| Independence Peak (Revolution Peak) | 6,974 m | 22,881 ft | Central Gorno-Badakhshan, south-east of Ismoil Somoni Peak | |

| Academy of Sciences Range | 6,785 m | 22,260 ft | North-western Gorno-Badakhshan, stretches in the north-south direction | |

| Karl Marx Peak | 6,726 m | 22,067 ft | GBAO, near the border to Afghanistan in the northern ridge of the Karakoram Range | |

| Garmo Peak | 6,595 m | 21,637 ft | Northwestern Gorno-Badakhshan. | |

| Mayakovskiy Peak | 6,096 m | 20,000 ft | Extreme south-west of GBAO, near the border to Afghanistan. | |

| Concord Peak | 5,469 m | 17,943 ft | Southern border in the northern ridge of the Karakoram Range | |

| Kyzylart Pass | 4,280 m | 14,042 ft | Northern border in the Trans-Alay Range | |

The Amu Darya and Panj rivers mark the border with Afghanistan, and the glaciers in Tajikistan's mountains are the major source of runoff for the Aral Sea. There are over 900 rivers in Tajikistan longer than 10 kilometres.

Administrative divisions

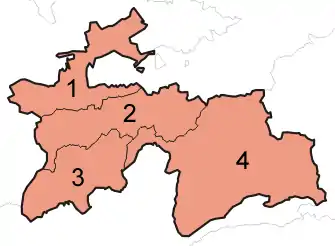

Tajikistan consists of 4 administrative divisions. These are the provinces (viloyat) of Sughd and Khatlon, the autonomous province of Gorno-Badakhshan (abbreviated as GBAO), and the Region of Republican Subordination (RRP – Raiony Respublikanskogo Podchineniya in transliteration from Russian or NTJ – Ноҳияҳои тобеи ҷумҳурӣ in Tajik; formerly known as Karotegin Province). Each region is divided into several districts (Tajik: Ноҳия, nohiya or raion), which in turn are subdivided into jamoats (village-level self-governing units) and then villages (qyshloqs). As of 2006, there were 58 districts and 367 jamoats in Tajikistan.[85]

| Division | ISO 3166-2 | Map No | Capital | Area (km2)[85] | Pop. (2019)[86] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sughd | TJ-SU | 1 | Khujand | 25,400 | 2,658,400 |

| Region of Republican Subordination | TJ-RR | 2 | Dushanbe | 28,600 | 2,122,000 |

| Khatlon | TJ-KT | 3 | Qurghonteppa | 24,800 | 3,274,900 |

| Gorno-Badakhshan | TJ-GB | 4 | Khorugh | 64,200 | 226,900 |

| Dushanbe | Dushanbe | 124.6 | 846,400 |

Lakes

About 2% of the country's area is covered by lakes, the best known of which are the following:

- Kayrakum (Qairoqqum) Reservoir (Sughd)

- Iskanderkul (Fann Mountains)

- Kulikalon (Kul-i Kalon) (Fann Mountains)

- Nurek Reservoir (Khatlon)

- Karakul (Kyrgyz: Кара-Көл; eastern Pamir)

- Sarez (Pamir)

- Shadau Lake (Pamir)

- Zorkul (Pamir)

Biodiversity

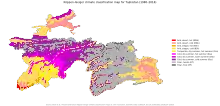

Tajikistan contains five terrestrial ecoregions: Alai-Western Tian Shan steppe, Gissaro-Alai open woodlands, Pamir alpine desert and tundra, Badghyz and Karabil semi-desert, and Paropamisus xeric woodlands.[87]

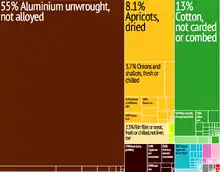

Economy

Nearly 47% of Tajikistan's GDP comes from immigrant remittances (mostly from Tajiks working in Russia).[88][89] The current economic situation remains fragile, largely owing to corruption, uneven economic reforms, and economic mismanagement. With foreign revenue precariously dependent upon remittances from migrant workers overseas and exports of aluminium and cotton, the economy is highly vulnerable to external shocks. In FY 2000, international assistance remained an essential source of support for rehabilitation programs that reintegrated former civil war combatants into the civilian economy, which helped keep the peace. International assistance also was necessary to address the second year of severe drought that resulted in a continued shortfall of food production. On 21 August 2001, the Red Cross announced that a famine was striking Tajikistan, and called for international aid for Tajikistan and Uzbekistan;[90] however, access to food remains a problem today. In January 2012, 680,152 of the people living in Tajikistan were living with food insecurity. Out of those, 676,852 were at risk of Phase 3 (Acute Food and Livelihoods Crisis) food insecurity and 3,300 were at risk of Phase 4 (Humanitarian Emergency). Those with the highest risk of food insecurity were living in the remote Murghob District of GBAO.[91]

Tajikistan's economy grew substantially after the war. The GDP of Tajikistan expanded at an average rate of 9.6% over the period of 2000–2007 according to the World Bank data. This improved Tajikistan's position among other Central Asian countries (namely Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan), which seem to have degraded economically ever since.[92] The primary sources of income in Tajikistan are aluminium production, cotton growing and remittances from migrant workers.[93] Cotton accounts for 60% of agricultural output, supporting 75% of the rural population, and using 45% of irrigated arable land.[94] The aluminium industry is represented by the state-owned Tajik Aluminum Company – the biggest aluminium plant in Central Asia and one of the biggest in the world.[95]

Tajikistan's rivers, such as the Vakhsh and the Panj, have great hydropower potential, and the government has focused on attracting investment for projects for internal use and electricity exports. Tajikistan is home to the Nurek Dam, the second highest dam in the world.[96] Lately, Russia's RAO UES energy giant has been working on the Sangtuda-1 hydroelectric power station (670 MW capacity) commenced operations on 18 January 2008.[97][98] Other projects at the development stage include Sangtuda-2 by Iran, Zerafshan by the Chinese company SinoHydro, and the Rogun power plant that, at a projected height of 335 metres (1,099 ft), would supersede the Nurek Dam as highest in the world if it is brought to completion.[99][100] A planned project, CASA-1000, will transmit 1000 MW of surplus electricity from Tajikistan to Pakistan with power transit through Afghanistan. The total length of transmission line is 750 km while the project is planned to be on Public-Private Partnership basis with the support of WB, IFC, ADB and IDB. The project cost is estimated to be around US$865 million.[101] Other energy resources include sizeable coal deposits and smaller, relatively unexplored reserves of natural gas and petroleum.[102]

In 2014 Tajikistan was the world's most remittance-dependent economy with remittances accounting for 49% of GDP and expected to fall by 40% in 2015 due to the economic crisis in the Russian Federation.[103] Tajik migrant workers abroad, mainly in the Russian Federation, have become by far the main source of income for millions of Tajikistan's people[104] and with the 2014–2015 downturn in the Russian economy the World Bank has predicted large numbers of young Tajik men will return home and face few economic prospects.[103]

According to some estimates about 20% of the population lives on less than US$1.25 per day.[105] Migration from Tajikistan and the consequent remittances have been unprecedented in their magnitude and economic impact. In 2010, remittances from Tajik labour migrants totalled an estimated $2.1 billion US dollars, an increase from 2009. Tajikistan has achieved transition from a planned to a market economy without substantial and protracted recourse to aid (of which it by now receives only negligible amounts), and by purely market-based means, simply by exporting its main commodity of comparative advantage — cheap labour.[106] The World Bank Tajikistan Policy Note 2006 concludes that remittances have played an important role as one of the drivers of Tajikistan's economic growth during the past several years, have increased incomes, and as a result helped significantly reduce poverty.[107]

Drug trafficking is the major illegal source of income in Tajikistan[108] as it is an important transit country for Afghan narcotics bound for Russian and, to a lesser extent, Western European markets; some opium poppy is also raised locally for the domestic market.[109] However, with the increasing assistance from international organisations, such as UNODC, and co-operation with the US, Russian, EU and Afghan authorities a level of progress on the fight against illegal drug-trafficking is being achieved.[110] Tajikistan holds third place in the world for heroin and raw opium confiscations (1216.3 kg of heroin and 267.8 kg of raw opium in the first half of 2006).[111][112] Drug money corrupts the country's government; according to some experts the well-known personalities that fought on both sides of the civil war and have held the positions in the government after the armistice was signed are now involved in the drug trade.[109] UNODC is working with Tajikistan to strengthen border crossings, provide training, and set up joint interdiction teams. It also helped to establish Tajikistani Drug Control Agency.[113] Tajikistan is also an active member of the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO).

Besides Russia, China is one of the major economic and trade partners of Dushanbe. Tajikistan belongs to the group of countries with a high debt trap risk associated with Chinese investment within the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) meaning that excessive reliance on Chinese loans may weaken country's ability to manage its external debt in a sustainable way.[114]

Transportation

In 2013 Tajikistan, like many of the other Central Asian countries, was experiencing major development in its transportation sector.

As a landlocked country Tajikistan has no ports and the majority of transportation is via roads, air, and rail. In recent years Tajikistan has pursued agreements with Iran and Pakistan to gain port access in those countries via Afghanistan. In 2009, an agreement was made between Tajikistan, Pakistan, and Afghanistan to improve and build a 1,300 km (810 mi) highway and rail system connecting the three countries to Pakistan's ports. The proposed route would go through the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Province in the eastern part of the country.[115] And in 2012, the presidents of Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Iran signed an agreement to construct roads and railways as well as oil, gas, and water pipelines to connect the three countries.[116]

Rail

The railroad system totals only 680 kilometres (420 mi) of track,[111] all of it 1,520 mm (4 ft 11 27⁄32 in) broad gauge. The principal segments are in the southern region and connect the capital with the industrial areas of the Hisor and Vakhsh valleys and with Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Russia.[117] Most international freight traffic is carried by train.[118] The recently constructed Qurghonteppa–Kulob railway connected the Kulob District with the central area of the country.[118]

Air

.jpg.webp)

In 2009 Tajikistan had 26 airports, 18 of which had paved runways, of which two had runways longer than 3,000 meters.[111] The country's main airport is Dushanbe International Airport, which as of April 2015 had regularly-scheduled flights to major cities in Russia, Central Asia, as well as Delhi, Dubai, Frankfurt, Istanbul, Kabul, Tehran, and Ürümqi, amongst others. There are also international flights, mainly to Russia, from Khujand Airport in the northern part of the country as well as limited international services from Kulob Airport, and Qurghonteppa International Airport. Khorog Airport is a domestic airport and also the only airport in the sparsely populated eastern half of the country.

Tajikistan has one major airline (Somon Air) and is also serviced by over a dozen foreign airlines.

Roads

The total length of roads in the country is 27,800 kilometres. Automobiles account for more than 90% of the total volume of passenger transportation and more than 80% of domestic freight transportation.[118]

In 2004 the Tajik–Afghan Friendship Bridge between Afghanistan and Tajikistan was built, improving the country's access to South Asia. The bridge was built by the United States.[119]

As of 2014 many highway and tunnel construction projects are underway or have recently been completed. Major projects include rehabilitation of the Dushanbe – Chanak (Uzbek border), Dushanbe – Kulma (Chinese border), and Kurgan-Tube – Nizhny Pyanj (Afghan border) highways, and construction of tunnels under the mountain passes of Anzob, Shakhristan, Shar-Shar[120] and Chormazak.[121] These were supported by international donor countries.[118][122]

Demographics

| Year | Million |

|---|---|

| 1950 | 1.5 |

| 2000 | 6.2 |

| 2018 | 9.1 |

Tajikistan has a population of 9,275,832 people, of which 70% are under the age of 30 and 35% are between the ages of 14 and 30.[89] Tajiks who speak Tajik (a dialect of Persian) are the main ethnic group, although there are sizeable minorities of Uzbeks and Russians, whose numbers are declining due to emigration.[125] The Pamiris of Badakhshan, a small population of Yaghnobi people, and a sizeable minority of Ismailis are all considered to belong to the larger group of Tajiks. All citizens of Tajikistan are called Tajikistanis.[111]

In 1989, ethnic Russians in Tajikistan made up 7.6% of the population, but they are now less than 0.5%, after the civil war spurred Russian emigration.[126] The ethnic German population of Tajikistan has also declined due to emigration: having topped at 38,853 in 1979, it has almost vanished since the collapse of the Soviet Union.[127]

Languages

The state and official language of the Republic of Tajikistan is Tajik, which is written in the Tajik Cyrillic alphabet. In fact, the Tajik language is a variant of the Persian language (or Farsi). This fact is also recognized by linguists. Therefore, Tajik speakers have no problems communicating with Persian speakers from Iran and Dari speakers from Afghanistan. Several million native Tajik speakers also live in neighboring Uzbekistan and Russia.[128]

Tajik became the official language of the Tajikistan Soviet Socialist Republic on July 22, 1989. Before that, since the creation of the Tajikistan SSR, the only official language of the republic was the Russian language, and the Tajik language had only the status of the “national language”. Russian lost its official status after Tajikistan's independence in late 1991. Despite this, according to article 2 of the Constitution of the Republic of Tajikistan, Russian language is recognized as the official language of inter-ethnic communication in the country. Approximately 90% of the population of Tajikistan speaks Russian at various levels. The highly educated part of the population of Tajikistan, as well as the Intelligentsia, prefer to speak Russian and Persian, the pronunciation of which in Tajikistan is called the “Iranian style”.[129][130][131]

Apart from Russian, Uzbek language is actually the second most widely spoken language in Tajikistan after Tajik. Native Uzbek speakers live in the north and west of Tajikistan. In the fourth place (after Tajik, Russian and Uzbek) by the number of native speakers are various Pamir languages whose native speakers live in Kuhistani Badakshshan Autonomus Region. The majority of Zoroastrian in Tajikistan speak it in the Pamir languages. Native speakers of the Kyrgyz language live in the north of Kuhistani Badakshshan Autonomus Region. Yagnobi language speakers live in the west of the country. The Parya language of local Romani people (Central Asian Gypsies) is also widely spoken in Tajikistan. Tajikistan also has small communities of native speakers of Persian, Arabic, Pashto, Eastern Armenian, Azerbaijani, Tatar, Turkmen, Kazakh, Chinese, Ukrainian.[132]

Among foreign languages, the most popular is English, which is taught in schools in Tajikistan as one of the foreign languages. Some young people, as well as those working in the tourism sector of Tajikistan, speak English at different levels. Of the European languages, there are also a sufficient number of native speakers of German and French. The Uzbek population is learning Turkish language.

Employment

In 2009 nearly one million Tajiks worked abroad (mainly in Russia).[133] More than 70% of the female population lives in traditional villages.[134]

Culture

The Tajik language is the mother tongue of around 80% of the citizens of Tajikistan. The main urban centres in today's Tajikistan include Dushanbe (the capital), Khujand, Kulob, Panjakent, Qurghonteppa, Khorugh and Istaravshan. There are also Uzbek, Kyrgyz and Russian minorities.[135]

The Pamiri people of Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Province in the southeast, bordering Afghanistan and China, though considered part of the Tajik ethnicity, nevertheless are distinct linguistically and culturally from most Tajiks. In contrast to the mostly Sunni Muslim residents of the rest of Tajikistan, the Pamiris overwhelmingly follow the Ismaili branch of Shia Islam, and speak a number of Eastern Iranian languages, including Shughni, Rushani, Khufi and Wakhi. Isolated in the highest parts of the Pamir Mountains, they have preserved many ancient cultural traditions and folk arts that have been largely lost elsewhere in the country.

The Yaghnobi people live in mountainous areas of northern Tajikistan. The estimated number of Yaghnobis is now about 25,000. Forced migrations in the 20th century decimated their numbers. They speak the Yaghnobi language, which is the only direct modern descendant of the ancient Sogdian language.[136]

Tajikistan artisans created the Dushanbe Tea House, which was presented in 1988 as a gift to the sister city of Boulder, Colorado.[137]

Religion

Sunni Islam of the Hanafi school has been officially recognised by the government since 2009.[140] Tajikistan considers itself a secular state with a Constitution providing for freedom of religion. The Government has declared two Islamic holidays, Eid ul-Fitr and Eid al-Adha, as state holidays. According to a US State Department release and Pew research group, the population of Tajikistan is 98% Muslim. Approximately 87%–95% of them are Sunni and roughly 3% are Shia and roughly 7% are non-denominational Muslims.[141][142] The remaining 2% of the population are followers of Russian Orthodoxy, Protestantism, Zoroastrianism and Buddhism. A great majority of Muslims fast during Ramadan, although only about one third in the countryside and 10% in the cities observe daily prayer and dietary restrictions.

Bukharan Jews had lived in Tajikistan since the 2nd century BCE, but today almost none are left. In the 1940s, the Jewish community of Tajikistan numbered nearly 30,000 people. Most were Persian-speaking Bukharan Jews who had lived in the region for millennia along with Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe who resettled there in the Soviet era. The Jewish population is now estimated at less than 500, about half of whom live in Dushanbe.[143]

Relationships between religious groups are generally amicable, although there is some concern among mainstream Muslim leaders that minority religious groups undermine national unity. There is a concern for religious institutions becoming active in the political sphere. The Islamic Renaissance Party (IRP), a major combatant in the 1992–1997 Civil War and then-proponent of the creation of an Islamic state in Tajikistan, constitutes no more than 30% of the government by statute. Membership in Hizb ut-Tahrir, a militant Islamic party which today aims for an overthrow of secular governments and the unification of Tajiks under one Islamic state, is illegal and members are subject to arrest and imprisonment.[144] Numbers of large mosques appropriate for Friday prayers are limited and some feel this is discriminatory.

By law, religious communities must register by the State Committee on Religious Affairs (SCRA) and with local authorities. Registration with the SCRA requires a charter, a list of 10 or more members, and evidence of local government approval prayer site location. Religious groups who do not have a physical structure are not allowed to gather publicly for prayer. Failure to register can result in large fines and closure of place of worship. There are reports that registration on the local level is sometimes difficult to obtain.[145] People under the age of 18 are also barred from public religious practice.[146]

As of January 2016, as part of an "anti-radicalisation campaign", police in the Khatlon region reportedly shaved the beards of 13,000 men and shut down 160 shops selling the hijab. Shaving beards and discouraging women from wearing hijab is part of a government campaign targeting trends that are deemed "alien and inconsistent with Tajik culture", and "to preserve secular traditions".[147]

Today, approximately 1.6% of the population in Tajikistan is Christian, mostly Orthodox Christians.[138][139]

The territory of Tajikistan is part of the Dushanbe and Tajikistan Diocese of the Central Asian Metropolitan District of the Russian Orthodox Moscow Patriarchate. The country is also home to communities of Catholics, Armenian Christians, Protestants, Lutherans, Jehovah's Witnesses, Baptists, Mormons, and Adventists.[148]

Health

Despite repeated efforts by the Tajik government to improve and expand health care, the system remains among the most underdeveloped and poor, with severe shortages of medical supplies. The state's Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare reported that 104,272 disabled people are registered in Tajikistan (2000). This group of people suffers most from poverty in Tajikistan. The government of Tajikistan and the World Bank considered activities to support this part of the population described in the World Bank's Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper.[149] Public expenditure on health was at 1% of the GDP in 2004.[150]

Life expectancy at birth was estimated to be 69 years in 2020.[151] The infant mortality rate was approximately 30.42 deaths per 1,000 children in 2018.[152] In 2014, there were 2.1 physicians per 1,000 people, higher than any other low-income country after North Korea.[153]

Tajikistan has experienced a sharp decrease in number of per capita hospital beds following the dissolution of the USSR (since 1992), even though the number still remains relatively at 4.8 beds per 1,000 people, well above the world average of 2.7 and one of the highest among other low-income countries.[154]

According to World Bank, 96% of births are attended by skilled health staff, a figure which has risen from 66.6% in 1999.[155]

In 2010 the country experienced an outbreak of polio that caused more than 457 cases of polio in both children and adults, and resulted in 29 deaths before being brought under control.[156]

Education

.jpg.webp)

Despite its poverty, Tajikistan has a high rate of literacy due to the old Soviet system of free education, with an estimated 99.8%[157] of the population having the ability to read and write.[111]

Public education in Tajikistan consists of 11 years of primary and secondary education but the government planned to implement a 12-year system in 2016.[158] There is a relatively large number of tertiary education institutions including Khujand State University which has 76 departments in 15 faculties,[158] Tajikistan State University of Law, Business, & Politics, Khorugh State University, Agricultural University of Tajikistan, Tajik National University, and several other institutions. Most, but not all, universities were established during the Soviet Era. As of 2008 tertiary education enrollment was 17%, significantly below the sub-regional average of 37%,[159] although higher than any other low-income country after Syria.[160] Many Tajiks left the education system due to low demand in the labour market for people with extensive educational training or professional skills.[159]

Public spending on education was relatively constant between 2005–2012 and fluctuated from 3.5% to 4.1% of GDP[161] significantly below the OECD average of 6%.[159] The United Nations reported that the level of spending was "severely inadequate to meet the requirements of the country’s high-needs education system."[159]

According to a UNICEF-supported survey, about 25 percent of girls in Tajikistan fail to complete compulsory primary education because of poverty and gender bias,[162] although literacy is generally high in Tajikistan.[150] Estimates of out of school children range from 4.6% to 19.4% with the vast majority being girls.[159]

In September 2017, the University of Central Asia will launch its second campus in Khorog, Tajikistan, offering majors in Earth & Environmental Sciences and Economics.[163]

Sport

The national sport of Tajikistan is gushtigiri, a form of traditional wrestling.[164][165]

Another popular sport is buzkashi, a game played on horseback, like polo. One plays it on one's own and in teams. The aim of the game is to grab a 50 kg dead goat, ride clear of the other players, get back to the starting point and drop it in a designated circle. It is also practised in Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. It is often played at Nowruz celebrations.[166]

.jpg.webp)

Tajikistan's mountains provide many opportunities for outdoor sports, such as hill climbing, mountain biking, rock climbing, skiing, snowboarding, hiking, and mountain climbing. The facilities are limited, however. Mountain climbing and hiking tours to the Fann and Pamir Mountains, including the 7,000 m peaks in the region, are seasonally organised by local and international alpine agencies.

Football is the most popular sport in Tajikistan. It is governed by the Tajikistan Football Federation. The Tajikistan national football team competes in FIFA and AFC competitions. The top clubs in Tajikistan compete in the Tajik League.[167][164]

The Tajikistan Cricket Federation was formed in 2012 as the governing body for the sport of cricket in Tajikistan. It was granted affiliate membership of the Asian Cricket Council in the same year.[168]

Rugby union in Tajikistan is a minor but growing sport.[167] In 2008, the sport was officially registered with the Ministry of Justice, and there are currently 3 men's clubs.[169]

Four Tajikistani athletes have won Olympic medals for their country since independence. They are: wrestler Yusup Abdusalomov (silver in Beijing 2008), judoka Rasul Boqiev (bronze in Beijing 2008), boxer Mavzuna Chorieva (bronze in London 2012) and hammer thrower Dilshod Nazarov (gold in Rio de Janeiro 2016).

Khorugh, capital of Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region, is the location of highest altitude where bandy has been played.[170]

Tajikistan has also one ski resort, called Safed Dara (formerly Takob), near the town of Varzob.[171]

See also

- Dushanbe

- Foreign relations of Tajikistan

- Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Province

- Index of Tajikistan-related articles

- Ittihodi Scouthoi Tojikiston

- Kingdom of Balhara

- List of cities in Tajikistan

- Mercy-Man

- Mount Imeon

- Outline of Tajikistan

- Russian Turkestan

- Telecommunications in Tajikistan

- Yaghnob Valley

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the CIA World Factbook website https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the CIA World Factbook website https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

- Constitution of Tajikistan

- Национальный состав, владение языками и гражданство населения Республики Таджикистан Том III. stat.tj

- "Central Intelligence Agency". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 7 February 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- M. A., Geography; B. A., Geography. "Ever Wonder What Residents of a Particular Country Are Called?". ThoughtCo.

- "General information". Embassy of the Republic of Tajikistan to France. 1 March 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

Territorу – 143.1 thsd. square kilometers

- "Demographic Yearbook – Table 3: Population by sex, rate of population increase, surface area and density" (PDF). United Nations Statistics Division. 2012: 6. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

Continent, country or area{...}Surface area Superficie (km²) 2012{...}Tajikistan – Tadjikistan{...}143 100

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Alex Sodiqov (24 January 2011). "Tajikistan cedes disputed land to China". Eurasia Daily Monitor. Jamestown Foundation. 8 (16). Retrieved 23 September 2018.

On January 12, the lower house of the Tajik parliament voted to ratify the 2002 border demarcation agreement, handing over 1,122 square kilometers (433 square miles) of mountainous land in the remote Pamir Mountains (www.asiaplus.tj, January 12). The ceded land represents about 0.8 percent of the country’s total area of 143,100 square kilometers (55,250 square miles).

- "Tajikistan Population (2020) - Worldometer". www.worldometers.info.

- "Population by Country (2020) - Worldometer". www.worldometers.info.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2018". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- "GINI index (World Bank estimate)". databank.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. pp. 343–346. ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- "КОНСТИТУЦИЯ РЕСПУБЛИКИ ТАДЖИКИСТАН". prokuratura.tj. Parliament of Tajikistan. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- "Tajikistan Population (2021) - Worldometer". www.worldometers.info.

- "Proto-urban Site of Sarazm". UNESCO.org. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 4 August 2014. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- Bergne, Paul (2007) The Birth of Tajikistan: National Identity and the Origins of the Republic, IB Taurus & Co Ltd, pg. 39–40

- "World Report 2019: Rights Trends in Tajikistan". Human Rights Watch. 15 January 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "Tajikistan Ethnic groups - Demographics". www.indexmundi.com.

- "What's the Story Behind All the 'Stans?". About.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- "-Stan". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- A Country Study: Tajikistan, Ethnic Background. Library of Congress Call Number DK851. K34 (1997)

- "معنی تاجیک | فرهنگ فارسی عمید". www.vajehyab.com. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "معنی تاجیک | لغتنامه دهخدا". www.vajehyab.com. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Anti-Armenian Riots Erupt in Soviet Republic of Tadzhikistan Archived 30 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Articles.latimes.com (2 November 1989). Retrieved on 20 January 2017.

- Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan : country studies Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, page 206

- Richard Foltz, A History of the Tajiks: Iranians of the East, London: Bloomsbury, 2019, pp. 33–61.

- Richard Nelson Frye, "Persien: bis zum Einbruch des Islam" (original English title: "The Heritage Of Persia"), German version, tr. by Paul Baudisch, Kindler Verlag AG, Zürich 1964, pp. 485–498

- Frye, Richard Nelson (1996). The heritage of Central Asia from antiquity to the Turkish expansion. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 4. ISBN 1-55876-110-1.

- Tajikistan: History Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Proto-urban Site of Sarazm – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". unesco.org. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- See: The Deeds of Harsha: Being a Cultural Study of Bāṇa's Harshacharita, 1969, p 199, Dr Vasudeva Sharana Agrawala; Proceedings and Transactions of the All-India Oriental Conference, 1930, p 118, Dr J. C. Vidyalankara; Prācīna Kamboja, jana aura janapada =: Ancient Kamboja, people and country, 1981, Dr Jiyālāla Kāmboja, Dr Satyavrat Śāstrī – Kamboja (Pakistan).

- C. Michael Hogan, ''Silk Road, North China'', The Megalithic Portal, ed. Andy Burnham Archived 2 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Megalithic.co.uk. Retrieved on 20 January 2017.

- Shiji, trans. Burton Watson

- Frances Wood (2002) The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. University of California Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-520-23786-5.

- Tajikistan Archived 21 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. loc.gov.

- "Encyclopedia – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". eb.com.

- Grousset, Rene (2004). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Svatopluk Soucek (2000). "Chapter 5 – The Qarakhanids". A history of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65704-4.

- ilak-khanids Archived 9 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine: Iranica. accessed May 2014.

- "Tajikistan profile - Timeline". BBC News. BBC. 31 July 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- "Tajikistan profile - Timeline". BBC News. 31 July 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- "History of Central Asia - Under Russian rule". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- Whitman, John (1956). Turkestan Cotton in Imperial Russia. Cambridge University: Association for Slavic and Eurasian Studies. pp. 190–205.

- Khalid, Adeeb. "Jadidism in Central Asia: Origins, Developement, and Fate Under the Soviets". Al Mesbar Studies and Research Centre. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Tajikistan - The Russian Conquest". Country Studies. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- Pipes, Richard (1955). "Muslims of Soviet Central Asia: Trends and Prospects (Part I)". Middle East Journal. 9 (2): 149–150. JSTOR 4322692.

- "A Country Study: Tajikistan, Impact of the Civil War". U.S. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- "Tajikistan – Collectivization". countrystudies.us. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012.

- "Tajikistan – The Purges". countrystudies.us. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012.

- Tajikistan – Ethnic Groups Archived 7 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Library of Congress

- "Tajikistan – The Postwar Period". countrystudies.us. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012.

- Kamoludin Abdullaev and Shahram Akbarzaheh (2010) Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan, 2nd ed. p. 383. ISBN 0810860619.

- Vadim Erlikman (2004). Poteri narodonaseleniia v XX veke. Moscow. pp. 23–35. ISBN 5-93165-107-1

- C. Peter Chen. "Tajikistan in World War II". WW2DB. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- Boris Rumer (1989) Soviet Central Asia: A Tragic Experiment, Unwin Hyman, London. p. 126. ISBN 0044451466.

- Statistical Yearbook of the USSR 1990, Goskomstat, Moscow, 1991, p. 115 (in Russian).

- Statistical Yearbook of the USSR 1990, Goskomstat, Moscow, 1991, p. 210 (in Russian).

- "Tajikistan celebrates Independence Day". Front News International. 9 September 2017. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- "Tajikistan: rising from the ashes of civil war". United Nations. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- "Human Rights Watch World Report 1994: Tajikistan". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- "Telling the truth for more than 30 years – Tajikistan After the Elections: Post-Soviet Dictatorship". Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. June 1995. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- Jim Nichol. "Central Asia's Security: Issues and Implications for U.S. Interests" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- "REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION". Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- "OSCE and CIS Observers Disagree on Presidential Election in Tajikistan". New Eurasia. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- "OSCE urges Tajikistan to stop attacks on free media". Reuters. 18 October 2010. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017.

- Kucera, Joshua (7 September 2010). "Tajikistan's Ayni airbase opens – but who is using it?". The Bug Pit – The military and security in Eurasia. The Open Society Institute. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- "Tajikistan: Dushanbe Dangling Ayni Air Base Before Russia". EurasiaNet.org. 19 October 2010. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- "Ratification of Russian military base deal provides Tajikistan with important security guarantees". Jane's. Archived from the original on 3 August 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- "Tajikistan says restive east is under control". BBC News. 18 October 2010. Archived from the original on 15 November 2013.

- "Tajikistan Says Kills Three Suspected Islamist Militants". Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. 18 October 2010. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- "Tajikistan: The government withdraws troops from the Rasht valley". Ferghana Information agency, Moscow. 3 November 2010. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- Khayrullo Fayz (24 July 2012). "Tajikistan clashes: 'Many dead' in Gorno-Badakhshan". BBC Uzbek. Archived from the original on 18 December 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- "Why Russia Will Send More Troops to Central Asia". Stratfor. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015.

- "Commander of elite Tajik police force defects to Islamic State". Reuters. 28 May 2015. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- "The Tajik civil war: Causes and dynamics". Conciliation Resources. 30 December 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "How The Tajik President Has Managed To Stay In Power For Nearly Three Decades". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- Greenberg, Ilan, "Media Muzzled and Opponents Jailed, Tajikistan Readies for Vote", The New York Times, 4 November 2006 (article dateline 3 November 2006), page A7, New York edition

- "Change you can't believe in". The Economist. 4 March 2010. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- "Tajikistan elections criticised by poll watchdog". BBC. 1 March 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- "Press TV – Iran makes move to join SCO". Presstv.ir. 24 March 2008. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Press freedom in Tajikistan: Going from bad to worse | DW | 05.06.2020". DW.COM. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- "Tajik Government's Fury Over Conflict Reporting". Iwpr.net. 22 October 2010. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- "Global democracy has another bad year". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Which Countries Are For or Against China's Xinjiang Policies?". The Diplomat. 15 July 2019.

- Population of the Republic of Tajikistan as of 1 January 2008, State Statistical Committee, Dushanbe, 2008 (in Russian)

- "Population size, Republic of Tajikistan on January 1, 2019" (PDF) (in Tajik). Tajikistan Statistics Agency. 2019. pp. 16–29. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Dinerstein, Eric; et al. (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568.

- "Remittance man Archived 18 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine". The Economist. 7 September 2013.

- Tajikistan: Building a Democracy (video) Archived 11 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations, March 2014

- "Spectre of famine over Tajikistan - IFRC". www.ifrc.org. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- "Integrated Food Security Phase Classification" (PDF). usaid.gov. USAID. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- "BBC's Guide to Central Asia". BBC News. 20 June 2005. Archived from the original on 1 December 2006. Retrieved 1 November 2006.

- "Background Note: Tajikistan". US Department of State, Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs. December 2007. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- "Tajikistan: Over 392.5 thousand tons of cotton picked in Tajikistan". BS-AGRO. 12 December 2013. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013.

- Алюминий по-таджикски [Aluminium in Tajiki]. Expert Kazakhstan (in Russian). 23 (25). 6 December 2004. Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- "Highest Dams (World and U.S.)". ICOLD World Register of Dams. 1998. Archived from the original on 5 April 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- Первая очередь Сангтудинской ГЭС в Таджикистане будет запущена 18 января [First stage of the Sangtuda HPS launched on 18 January] (in Russian). Vesti. 25 December 2007. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- "Sangtuda-1 HPS launched on January 18, 2008". Today Energy. 5 January 2008. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- "Iran participates in power plant project in Tajikistan". IRNA. 24 April 2007. Archived from the original on 28 April 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- "Chinese To Build Tajik Hydroelectric Plant". Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty. 18 January 2007. Archived from the original on 15 March 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- "Pakistan can end power crisis thru CASA-1000". The Gazette of Central Asia. Satrapia. 13 August 2011. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- "Tajikistan". www.eu4energy.iea.org. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- "Tajikistan: Remittances to Plunge 40% – World Bank". EurasiaNet.org. Archived from the original on 29 May 2015.

- Dilip Ratha; Sanket Mohapatra; K. M. Vijayalakshmi; Zhimei Xu (29 November 2007). "Remittance Trends 2007. Migration and Development Brief 3" (PDF). World Bank. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- "UNDP: Human development indices – Table 3: Human and income poverty (Population living below national poverty line (2000–2007))" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- Alexei Kireyev (January 2006). "The Macroeconomics of Remittances: The Case of Tajikistan. IMF Working Paper WP/06/2" (PDF). IMF. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- "Tajikistan Policy Note. Poverty Reduction and Enhancing the Development Impact of Remittances. Report No. 35771-TJ" (PDF). World Bank. June 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- MEET THE STANS – episodes 3&4: Uzbekistan and Tajikistan Archived 3 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 2011

- "Country Factsheets, Eurasian Narcotics: Tajikistan 2004" (PDF). Silk Road Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2013.

- Roger McDermott (10 January 2006). "Dushanbe looks towards Afghanistan to combat drug trafficking". Eurasia Daily Monitor. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- CIA World Factbook. Tajikistan

- "Facts and Figures". Coordination and Analysis Unit of the UNODC Regional Office for Central Asia. Archived from the original on 28 April 2007.

- "Fighting Drugs, Crime and Terrorism in the CIS". UNODC. 4 October 2007.

- Vakulchuk, Roman and Indra Overland (2019) “China’s Belt and Road Initiative through the Lens of Central Asia”, in Fanny M. Cheung and Ying-yi Hong (eds) Regional Connection under the Belt and Road Initiative. The Prospects for Economic and Financial Cooperation. London: Routledge, pp. 115–133.

- "President Zardari chairs PPP consultative meeting". Associated Press of Pakistan. 10 August 2009. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- "Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan sign agreement on road, railway construction". Tehran Times. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- Migrant Express Part 1: Good-bye Dushanbe. YouTube. 1 September 2009. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- Administrator. "Tajikistan Mission – Infrastructure". tajikistanmission.ch. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014.

- "US Army Corps of Engineer, Afghanistan-Tajikistan Bridge". US Army Corps of Engineer. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- Shar-Shar auto tunnel links Tajikistan to China Archived 31 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The 2.3 km (1 mi) Shar-Shar car tunnel linking Tajikistan and China opened to traffic on 30 Aug.., Siyavush Mekhtan, 3 September 2009

- Payrav Chorshanbiyev (12 February 2014) Chormaghzak Tunnel renamed Khatlon Tunnel and Shar-Shar Tunnel renamed Ozodi Tunnel Archived 31 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine. news.tj

- Trade, tunnels, transit and training in mountainous Tajikistan Archived 19 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine. fco.gov.uk (7 May 2013)

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- Russians left behind in Central Asia Archived 11 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Robert Greenall, BBC News, 23 November 2005.

- Tajikistan – Ethnic Groups Archived 7 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Source: U.S. Library of Congress.

- Russian-Germans in Tajikistan Archived 20 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Pohl, J. Otto. "Russian-Germans in Tajikistan", Neweurasia, 29 March 2007.

- "Tajik language". Britannica. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Tajikistan Drops Russian As Official Language". RFE/RL – Rferl.org. 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- "The status of the Russian language in Tajikistan remains unchanged – Rahmon". RIA – RIA.ru. 22 October 2009. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- "В Таджикистане русскому языку вернули прежний статус". Lenta.ru. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- Sen Nag, Oishimaya. "What Languages Are Spoken In Tajikistan". World Atlas. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- Deployment of Tajik workers gets green light Archived 10 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Arab News. 21 May 2007.

- Azimova, Aigul; Abazbekova, Nazgul (27 July 2011). "Millennium Development Goals: Saving women's Lives". D+C. p. 289. Archived from the original on 17 February 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- "Tajikistan - People". Britannica. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Award-winning Yaghnobi-Czech dictionary captures dying language". Charles University. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- The Dushanbe-Boulder tea house. boulder-dushanbe.org

- Religious Composition by Country, 2010–2050 | Pew Research Center Archived 2 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Pewforum.org (2 April 2015). Retrieved on 20 January 2017.

- Tajikistan – Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project Archived 9 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Globalreligiousfutures.org. Retrieved on 20 January 2017.

- Avaz Yuldashev (5 March 2009). «Ханафия» объявлена официальным религиозным течением Таджикистана ["Hanafi" declared the official religious movement in Tajikistan] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 25 August 2010.

- Pew Forum on Religious & Public life, Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation Archived 26 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 29 October 2013.

- "Background Note: Tajikistan". State.gov. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- "Home Stand". Tablet Magazine. 4 January 2011. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015.

- "Hizb ut Tahrir". BBC News. BBC. 27 August 2003. Archived from the original on 13 September 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- TAJIKISTAN: Religious freedom survey, November 2003 Archived 13 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine -Forum 18 News Service, 20 November 2003

- U. S. Department of State International Religious Freedom Report for 2013, Executive Summary retrieved 2 August 2014.

- Sarkorova, Anora (21 January 2016). "Tajikistan's battle against beards". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- "Tajikistan - Religion". Country Studies. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Tajikistan – Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP) and joint assessment". World Bank. 31 October 2002. pp. 1–0. Archived from the original on 26 May 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2006.

- "Human Development Report 2009 – Tajikistan". Hdrstats.undp.org. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- "Field Listing :: Life expectancy at birth — The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- "Child Mortality – Tajikistan".

- "Physicians (per 1,000 people) – Tajikistan, Low income | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- "Hospital beds (per 1,000 people) – World, Tajikistan, Low income | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- "Births attended by skilled health staff (% of total) – Tajikistan, Low income | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- "2010 polio outbreak in Tajikistan: A reminder of the continued need for vigilance as the Region marks 10 years of polio-free status". World Health Organization. 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- "Tajikistan". uis.unesco.org. 27 November 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Tajikistan Education System". classbase.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014.

- Education in Tajikistan Archived 6 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine. unicef.org

- "School enrollment, tertiary (% gross) – Low income | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Tajikistan, Public spending on education, total (% of GDP) Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine World Bank

- "Tajikistan hosts education forum". News note. UNICEF. 9 June 2005. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- "University of Central Asia - University of Central Asia". www.ucentralasia.org. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016.

- Ibbotson, Sophie; Lovell-Hoare, Max (2013). Tajikistan. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-84162-455-6.

- "Tajikistan National Sport - Gushtigiri, Then And Now". Bjj Eastern Europe. 30 June 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- Abdullaev, Kamoludin; Akbarzaheh, Shahram (27 April 2010). Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan. Scarecrow Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-8108-7379-7.

- "Sport in Tajikistan". www.topendsports.com. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- "Cricket in Tajikisyan". Emerging Cricket. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Таъсиси нахустин тими духтаронаи рогбӣ дар Тоҷикистон" [Establishment of the first girls' rugby team in Tajikistan]. BBC Tajik/Persian (in Tajik). Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- "Google Translate". google.co.uk.

- "Safed Dara". Trip Advisor. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017.

Further reading

- Kamoludin Abdullaev and Shahram Akbarzadeh, Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan, 3rd. ed., Rowman & Littlefield, 2018.

- Shirin Akiner, Mohammad-Reza Djalili and Frederic Grare, eds., Tajikistan: The Trials of Independence, Routledge, 1998.

- Richard Foltz, A History of the Tajiks: Iranians of the East, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019.

- Robert Middleton, Huw Thomas and Markus Hauser, Tajikistan and the High Pamirs, Hong Kong: Odyssey Books, 2008 (ISBN 978-9-622177-73-4).

- Nahaylo, Bohdan and Victor Swoboda. Soviet Disunion: A History of the Nationalities problem in the USSR (1990) excerpt

- Kirill Nourdhzanov and Christian Blauer, Tajikistan: A Political and Social History, Canberra: ANU E-Press, 2013.