Tax expenditure

A tax expenditure program is government spending through the tax code. Tax expenditures alter the horizontal and vertical equity of the basic tax system by allowing exemptions, deductions, or credits to select groups or specific activities. For example, two people who earn exactly the same income can have different effective tax rates if one of the tax payers qualifies for certain tax expenditure programs by owning a home, having children, and receiving employer health care and pension insurance.

The history of tax expenditures

In 1967, the tax expenditure concept was created by Stanley S. Surrey, former Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, as a way to represent the political use of tax breaks for means that were usually accomplished through budget spending. Secretary Surrey argued that members of Congress were using tax policy as a ``vast subsidy apparatus to reward favored constituencies or subsidize narrow policy areas.[1] The Congressional Budget and Impoundment Act of 1974 (CBA) defines tax expenditures as "those revenue losses attributable to provisions of the Federal tax laws which allow a special credit, a preferential rate of tax, or a deferral of tax liability" (Surrey 1985). They are equally common in other countries.[2]

The process of tax expenditures

The Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation (hereafter JCT) annually estimates tax expenditures in terms of revenues lost to the U.S. Treasury for each special tax provision included in the U.S. tax code. In 2009, the JCT listed over 180 tax expenditure programs that cost the U.S. government over $1 trillion in revenues. Their cost varies with the level of economic activity.[3] A major tax expenditure is enjoyed by tax payers who own their own home and can deduct the interest on their mortgage payments. Since tax expenditures are claimed against a progressive tax code, individual tax expenditure programs are worth more to wealthier taxpayers.[4] The majority of tax expenditure programs are targeted for private social benefits and services.[5] The administration of tax expenditures falls on the IRS, and is not accounted for.

The politics of tax expenditures

Tax expenditures are considered "off-budget" spending by most economists and budget experts.[6] Tax expenditures are easier to pass through Congress than increases in appropriations spending. They are easily seen as free benefits, when government grants are viewed as giveaways.[7] Unlike direct spending, tax spending must only pass through two committees, the House Ways and Means and Senate Finance. Tax expenditure programs, once in the tax code, do not come up for annual review and can only be removed through tax legislation. Tax expenditure programs are a form of entitlement spending in that every tax payer that qualifies can claim government money. Faricy (2011) demonstrated that when tax expenditures are counted as a type of government spending, Democratic and Republican parties are indistinguishable in annual changes to federal government spending. This study also finds that Republicans are more likely to increase tax expenditures when in control of government thereby subsidizing the activities of businesses and the wealthy.[5] Jacob Hacker (2002) shows that the federal subsidization of private health insurance has grown over the years and has made efforts for nationalized health care more difficult. Ellis and Faricy (2011) find that when tax expenditures rise, public opinion adjusts and becomes more liberal to counteract the conservative policies.

The effect of tax expenditures

Partial exemption of the poor from taxation through reliance on progressive income taxes rather than sales taxes for revenue or tax rebates such as the earned income tax credit loosely correlate with socio-economic mobility in the United States with areas which tax the poor heavily such as the Deep South showing lower mobility than those with generous tax expenditures for the benefit of low income families with children.[8][9]

Size of expenditures in U.S.

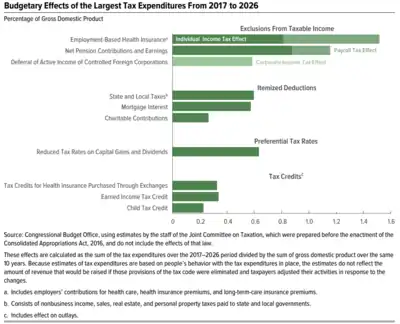

A 2016 Congressional Budget Office report estimated that U.S. tax expenditures were expected to total $1.5 trillion in 2016; for scale, U.S. federal tax receipts were expected to be $3.3 trillion that year. CBO also estimated the size of major tax expenditures on federal receipts as an annual average percent of GDP, for the 2016 to 2026 periods. These included, among others:

- Exclusions from income: Employment based health insurance (1.5% GDP) and pension contributions (1.2% GDP)

- Deductions from income: State and local taxes (0.6% GDP) and mortgage interest (0.6% GDP)

- Preferential (lower) tax rates: Capital gains and dividends (0.6% GDP)

- Tax credits: Earned income tax credit (0.3% GDP)

CBO projected that the top 10 largest tax expenditures would average 6.2% GDP each year on average over the 2016-2026 period. For scale, federal tax receipts averaged around 18% GDP from 1970 to 2016. The CBO analysis does not account for behavioral changes that might occur if the tax policies were changed, so the actual revenue impact would differ from the amounts indicated.[10]

Distribution of benefits in U.S.

According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), tax expenditures dis-proportionally benefit those with high incomes. CBPP estimated that the top 1% of U.S. households by income received approximately 17% of the tax expenditure benefits in 2013, while the top 20% received 51%.[11] The top 20% pay 84% of the federal income taxes; this figure does not include payroll taxes.[12] For scale, 50% of the $1.5 trillion in tax expenditures in 2016 is $750 billion, while the U.S. budget deficit was approximately $600 billion. In other words, eliminating the tax expenditures for just the top 20% could theoretically balance the budget in the short-run, although economic effects from changing the incentives may reduce the impact on the deficit.

CBO reported in January 2016 that: "Tax expenditures are distributed unevenly across the income scale. When measured in dollars, much more of the tax expenditures go to higher-income households than to lower-income households. As a percentage of people’s income, tax expenditures are greater for the highest-income and lowest-income households than for households in the middle of the income distribution."[13]

References

- Surrey 1973, p. 6

- Christian M.A. Valenduc, Hana Polackova Brixi, Zhicheng Li Swift: Tax Expenditures - Shedding Light on Government Spending Through the Tax System: Lessons from Developed and Transition Economies; World Bank Publications, 31 Jan 2003

- Thomas L. Hungerford: Tax Expenditures and the Federal Budget; Congressional Research Service, RL34622, 1 June 2011.

- Burman, Leonard E; Geissler, Christopher; Toder, Eric J (2008). "How Big Are Total Individual Income Tax Expenditures, and Who Benefits from Them?" (PDF). American Economic Review. 98 (2): 79–83. doi:10.1257/aer.98.2.79. JSTOR 29729999.

- Faricy 2011

- Howard 1997

- Leonard E. Burman: Is the Tax Expenditure Concept Still Relevant?; National Tax Journal, September 2003

- Hendren, Nathaniel; Patrick Kline; Emmanuel Saez (July 2013). "The Economic Impacts of Tax Expenditures Evidence from Spatial Variation Across the U.S" (PDF). equality-of-opportunity.org. Archived from the original (Revised draft) on 2013-08-09.

We focus on intergenerational mobility because many tax expenditures are loosely motivated by the goal of expanding opportunities for upward income mobility for low-income families. For example, deductions for education and health costs, progressive federal tax deductions for state income taxes, and tax credits aimed at low-income families such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) all are targeted toward providing increased resources to low income families with children.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help); External link in|publisher=(help) - David Leonhardt (July 22, 2013). "In Climbing Income Ladder, Location Matters: A study finds the odds of rising to another income level are notably low in certain cities, like Atlanta and Charlotte, and much higher in New York and Boston". The New York Times. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- CBO Budget & Economic Outlook 2016 to 2026-January 25, 2016-Pages 101 to 105

- CBPP-Policy Basics-Federal Tax Expenditures-Updated February 23, 2016

- Saunders, Laura (2015-04-10). "Top 20% of Earners Pay 84% of Income Tax". Wall Street Journal.

- CBO Budget & Economic Outlook 2016 to 2026-January 25, 2016-Pages 101 to 105

Further reading

- Faricy, Christopher (2011). "The Politics of Social Policy in America: The Causes and Effects of Indirect versus Direct Social spending". The Journal of Politics. 73 (1): 74–83. doi:10.1017/S0022381610000873. S2CID 154998866.

- Ellis, Christoper and Christopher Faricy. 2011. Social Policy and Public Opinion: How the Ideological Direction of Spending Influences Public Mood. (Forthcoming at The Journal of Politics).

- Hacker, Jacob S. 2002. The Divided Welfare State: The Battle over Public and Private Social Benefits in the United States. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Howard, Christopher. 1997. The Hidden Welfare State: Tax Expenditures and Social Policy in the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Surrey, Stanley S. 1974. Pathways to Tax Reform: The Concept of Tax Expenditures. Cambridge. Harvard University Press.