Tegucigalpa

Tegucigalpa (UK: /tɛˌɡuːsɪˈɡælpə/,[10] US: /təˌ-/,[11][12] Spanish: [teɣusiˈɣalpa]), formally Tegucigalpa, Municipality of the Central District (Spanish: Tegucigalpa, Municipio del Distrito Central or Tegucigalpa, M.D.C.[13]), and colloquially referred to as Tegus or Teguz,[14] is the capital and largest city of Honduras along with its twin sister, Comayagüela.[15]

Tegucigalpa | |

|---|---|

City and Capital | |

| Tegucigalpa, Municipio del Distrito Central | |

| |

Flag | |

| Nickname(s): | |

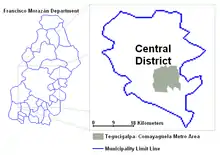

Location of the Central District within the Department of Francisco Morazán | |

Tegucigalpa Location of Tegucigalpa, M.D.C. in Honduras  Tegucigalpa Tegucigalpa (North America) | |

| Coordinates: 14°6′N 87°13′W | |

| Country | Honduras |

| Department | Francisco Morazán |

| Municipality | Central District |

| Founded | 29 September 1578 |

| Capital | 30 October 1880 |

| Merged as Central District | 30 January 1937 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-Council |

| • Body | Municipal Corporation |

| • Mayor | Nasry Asfura (PNH) |

| • Vice Mayor | Juan García[3] |

| • Aldermen | |

| • Municipal Secretary | Cosette Lopez Osorio |

| Area | |

| • City and Capital | 1,502 km2 (580 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 201.5 km2 (77.8 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 990 m (3,250 ft) |

| Population (2020 projection)[6] | |

| • City and Capital | 1,276,738 |

| • Density | 850/km2 (2,200/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,157,744 |

| Demonym(s) | Spanish:tegucigalpense, comayagüelense, capitalino(a) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central America) |

| Postal code | |

| Area code(s) | (country) +504 (city) 2[9] |

| Annual budget (2008) | 1.555 billion lempiras (US$82,190,000) |

| Website | Government of Tegucigalpa |

Claimed on 29 September 1578 by the Spaniards,[16] Tegucigalpa became the country's capital on October 30, 1880, under President Marco Aurelio Soto, when he moved the capital from Comayagua.[17] The Constitution of Honduras, enacted in 1982, names the sister cities of Tegucigalpa[a] and Comayagüela[b] as a Central District[c] to serve as the permanent national capital, under articles 8 and 295.[18][19]

After the dissolution of the Federal Republic of Central America in 1841, Honduras became an individual sovereign nation with Comayagua as its capital. The capital was moved to Tegucigalpa in 1880. On January 30, 1937, Article 179 of the 1936 Honduran Constitution was changed under Decree 53 to establish Tegucigalpa and Comayagüela as a Central District.[20]

Tegucigalpa is located in the southern-central highland region known as the department of Francisco Morazán of which it is also the departmental capital.[21] It is situated in a valley, surrounded by mountains. Tegucigalpa and Comayagüela, being sister cities, are physically separated by the Choluteca River.[22] The Central District is the largest of the 28 municipalities in the Francisco Morazán department.[23]

Tegucigalpa is Honduras' largest and most populous city as well as the nation's political and administrative center. Tegucigalpa is host to 25 foreign embassies and 16 consulates.[24][25] It is the home base of several state-owned entities such as ENEE and Hondutel, the national energy and telecommunications companies, respectively.[26] The city is also home to the country's most important public university, the National Autonomous University of Honduras,[27] as well as the national soccer team.[28] The capital's international airport, Toncontín, is known for its extremely short runway and the unusual maneuvers pilots must undertake upon landing or taking off to avoid the nearby mountains.[29][30][31]

The Central District Mayor's Office (Alcaldia Municipal del Distrito Central) is the city's governing body,[32] headed by a mayor[33] and 10 aldermen forming the Municipal Corporation (Corporación Municipal).[34] Being the department's seat as well, the governor's office of Francisco Morazán is also located in the capital. In 2008, the city operated on an approved budget of 1.555 billion lempiras (US$82,189,029).[35] In 2009, the city government reported a revenue of 1.955 billion lempiras (US$103,512,220), more than any other capital city in Central America except Panama City.

Tegucigalpa's infrastructure has not kept up with its population growth.[36] Deficient urban planning,[37] densely condensed urbanization, and poverty[38] are ongoing problems.[39] Heavily congested roadways where road infrastructure is unable to efficiently handle over 400,000 vehicles create havoc on a daily basis.[40] Both national and local governments have taken steps to improve and expand infrastructure as well as to reduce poverty in the city.[41][42]

Etymology

Most sources indicate the origin and meaning of the word Tegucigalpa is derived from the Nahuatl language.[43] The most widely accepted version suggests that it comes from the Nahuatl word Taguz-galpa, which means "hills of silver", but this interpretation is uncertain since the natives who occupied the region at time were unaware of the existence of mineral deposits in the area.

Another source suggests that Tegucigalpa derives from another language in which it means painted rocks, as explained by Leticia Oyuela in her book Minimum History of Tegucigalpa.[44] Other theories indicate it may derive from the term Togogalpa, which refers to tototi (small green parrot, in Nahuatl) and Toncontín, a small town near Tegucigalpa (toncotín was a Mexican dance of Nahuatl origin).[45][46]

In Mexico, it is believed the word Tegucigalpa is from the Nahuatl word Tecuztlicallipan, meaning "place of residence of the noble" or Tecuhtzincalpan, meaning "place on the home of the beloved master".[47]

Honduran philologist Alberto de Jesús Membreño, in his book Indigenous Toponymies of Central America, states that Tegucigalpa is a Nahuatl word meaning "in the homes of the sharp stones" and rules out the traditional meaning "hills of silver" arguing that Taguzgalpa was the name of the ancient eastern zone of Honduras.[48]

History

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Tegucigalpa was founded by Spanish settlers as Real de Minas de San Miguel de Tegucigalpa on September 29, 1578 on the site of an existing native settlement of the Lenca and Tolupans.[49] The first mayor of Tegucigalpa was Juan de la Cueva, who took office in 1579.[50] The Dolores Church (1735), the San Miguel Cathedral (1765), the Casa de la Moneda (1780), and the Immaculate Conception Church (1788) were some of the first important buildings constructed.[51]

Almost 200 years later, on June 10, 1762, this mining town became Real Villa de San Miguel de Tegucigalpa y Heredia under the rule of Alonso Fernández de Heredia, then-acting governor of Honduras. The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw disruption in Tegucigalpa's local government, from being extinguished in 1788 to becoming part of Comayagua in 1791 to returning to self-city governance in 1817.[52]

In 1817, then-mayor Narciso Mallol started the construction of the first bridge, a ten-arch masonry, connecting both sides of the Choluteca River. Upon completion four years later, it linked Tegucigalpa with her neighbor city of Comayagüela.[53] In 1821, Tegucigalpa legally became a city.[54] In 1824, the first Congress of the Republic of Honduras declared Tegucigalpa and Comayagua, then the two most important cities in the country, to alternate as capital of the country.[55]

After October 1838, following Honduras' independence as a single republic, the capital continued to switch back and forth between Tegucigalpa and Comayagua until October 30, 1880, when Tegucigalpa was declared the permanent capital of Honduras by then-president Marco Aurelio Soto.[17] A popular myth claims that the society of Comayagua, the long-time colonial capital of Honduras, publicly disliked the wife of President Soto, who took revenge by moving the capital to Tegucigalpa.[56] A more likely theory is that the change took place because President Soto was an important partner of the Rosario Mining Company, an American silver mining company, whose operations were based in San Juancito, close to Tegucigalpa, and he needed to be close to his personal interests.[57]

By 1898, it was decided that both Tegucigalpa and Comayagüela, being neighbor cities on the banks of the Choluteca River, would form the capital, but with separate names and separate local governments.[58] During this period, both cities had a population of about 40,000 people.

Between the 1930s and 1960s, Tegucigalpa continued to grow reaching a population of over 250,000 people, giving way to what would become one of the biggest neighborhoods in the city, the Colonia Kennedy; the nation's autonomous university, the UNAH; and the construction of the Honduras Maya Hotel.[59] It still remained relatively small and provincial until the 1970s, when migration from the rural areas began in earnest. During the 1980s, several avenues, traffic overpasses, and large buildings were erected, a relative novelty to a city characterized until then by two-story buildings.[60] However, lacking the enforcement of city planning and zoning laws, it led to highly disorganized urbanization. This lack of proper urbanization as the population has grown is evident on the surrounding slopes of the several hills in the city where some of the city's most impoverished neighborhoods have prevailed.[61]

On October 30, 1998, Hurricane Mitch devastated the capital, along with the rest of Honduras.[62] For five days, Mitch pounded the country creating devastating landslides and floods, causing the death of thousands as well as heavy deforestation and the destruction of thousands of homes.[63] A portion of Comayagüela was destroyed along with several neighborhoods on both sides of the Honduran capital. After the hurricane, infrastructure in Tegucigalpa was severely damaged. Even 12 years later, remnants of Hurricane Mitch were still visible, especially along the banks of the Choluteca River.[64][65]

Today, Tegucigalpa continues to sprawl far beyond its former colonial core: towards the east, south and west, creating a large but disorganized metropolis. In an effort to modernize the capital, increase its infrastructure and improve the quality of life of its inhabitants, the administration has passed several ordinances and projects to turn the city around within the upcoming years.[66]

Geography

Tegucigalpa is located on a chain of mountains with elevations of 975 metres (3,199 ft) at its lowest points and 1,463 metres (4,800 ft) at its highest suburban areas. Like most of the interior highlands of Honduras, the majority of Tegucigalpa's current area was occupied by open woodland. The area surrounding the city continues to be open woodland supporting pine forest interspersed with some oak, scrub, and grassy clearings as well as needle leaf evergreen and broadleaf deciduous forest.

The metropolitan area of both Tegucigalpa and Comayagüela covers a total area of 201 square kilometers (77.6 sq mi) while the entire Municipality of the Central District covers a total area of 1,396 square kilometers (539.1 sq mi).[5] Geological faults that are a threat to the neighborhoods on and below the hill have been identified in the District's high regions surrounding the capital.[67]

The Choluteca River, which crosses the city from south to north, physically separates Tegucigalpa and Comayagüela.[68] El Picacho Hill, a rugged mountain of moderate height, rises above the downtown area; several neighborhoods, both upscale residential and lower income, are located on its slopes. The city consists of gentle hills, and the ring of mountains surrounding the city tends to trap pollution.[69] During the dry season, a dense cloud of smog lingers in the basin until the first rains fall.

Tucked into a valley and bisected by a river, Tegucigalpa is prone to flooding during the rainy season, as experienced to the fullest during Hurricane Mitch and to a lesser degree every year during the rainy season. Despite being several thousand feet above sea level, the city lacks an efficient flood control system, including canals and sewerage powerful enough to channel rainwater back into the river to flow down to the ocean. The river itself is a threat since it isn't deep enough below the streets, nor are there levees high enough to prevent it from breaking out.[70] There are more than 100 neighborhoods deemed zones of high risk, several of them ruled out as uninhabitable in their entirety.[61]

There is a reservoir, known as Embalse Los Laureles, west of the city providing 30 percent of the city's water supply as well as a water treatment plant south of the city about 7.3 kilometres (4.5 mi) from the airport; part of the Concepción Reservoir just 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) southwest of the water plant.[71]

The Central District shares borders with 13 other municipalities of Francisco Morazán:[23] (to the north) Cedros and Talanga; (south) Ojojona, Santa Ana, San Buenaventura and Maraita; (east) San Juan de Flores, Villa de San Francisco, Santa Lucía, Valle de Ángeles, San Antonio de Oriente, and Tatumbla; (and to the west) Lepaterique. It is also bordered on the west by two municipalities of the Comayagua Department, Villa de San Antonio[72] and Lamaní, with the latter exactly at the quadripoint where the Central District, Lepaterique, Villa de San Antonio and Lamaní all meet.

Climate

Tegucigalpa features a more moderate form of a tropical wet and dry climate. Of the major Central American cities, Tegucigalpa's climate is among the most pleasant due to its high altitude.[73] Like much of central Honduras, the city has a tropical climate, though tempered by the altitude—meaning less humid than the lower valleys and the coastal regions—with even temperatures averaging between 19 °C (66 °F) and 23 °C (73 °F) degrees.[74]

The months of December and January are coolest, with an average min/ low temperature of 14 °C (57 °F); whereas March and April—popularly associated with Holy Week's holidays—are hottest and temperatures can reach up to 40 °C (104 °F) degrees on the hottest day.[75] The dry season lasts from November through April and the rainy season from May through October.[76] There is an average of 107 rainy days in the year, June and September usually the wettest months.

The average sunshine hours per month during the year is 211.2 and the average rainy days per month is 8.9. The average sunshine hours during the dry season is 228 per month while 182.5 millimetres (7.19 in) is the average monthly precipitation during the wet season. The wettest months of the rainy season are May—June and September—October, averaging 16.2 rainy days during each of those periods.

| Climate data for Tegucigalpa (Tegucigalpa Airport) 1961–1990, extremes 1951–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.0 (91.4) |

34.5 (94.1) |

35.5 (95.9) |

36.6 (97.9) |

36.9 (98.4) |

34.5 (94.1) |

35.9 (96.6) |

36.9 (98.4) |

34.2 (93.6) |

34.8 (94.6) |

32.8 (91.0) |

31.4 (88.5) |

36.9 (98.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 25.7 (78.3) |

27.4 (81.3) |

29.5 (85.1) |

30.2 (86.4) |

30.2 (86.4) |

28.6 (83.5) |

27.8 (82.0) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.5 (83.3) |

27.3 (81.1) |

26.0 (78.8) |

25.4 (77.7) |

27.9 (82.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 19.5 (67.1) |

20.4 (68.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.6 (74.5) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.2 (72.0) |

21.5 (70.7) |

20.4 (68.7) |

19.7 (67.5) |

21.7 (71.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 14.3 (57.7) |

14.5 (58.1) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.1 (62.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.0 (64.4) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.9 (64.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

16.3 (61.3) |

15.0 (59.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 4.5 (40.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

4.7 (40.5) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

12.6 (54.7) |

12.2 (54.0) |

11.0 (51.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.7 (45.9) |

6.8 (44.2) |

4.5 (40.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 5.3 (0.21) |

4.7 (0.19) |

9.9 (0.39) |

42.9 (1.69) |

143.5 (5.65) |

158.7 (6.25) |

82.3 (3.24) |

88.5 (3.48) |

177.2 (6.98) |

108.9 (4.29) |

39.9 (1.57) |

9.9 (0.39) |

871.7 (34.32) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 12 | 9 | 9 | 13 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 73 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71 | 66 | 62 | 60 | 67 | 75 | 74 | 73 | 76 | 78 | 77 | 75 | 71 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 220.8 | 229.4 | 268.5 | 242.8 | 216.3 | 171.7 | 192.5 | 204.8 | 183.4 | 200.4 | 199.2 | 212.2 | 2,542 |

| Source 1: NOAA[77] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (humidity, 1951–1993)[78] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[79] | |||||||||||||

Hurricane Mitch

Tegucigalpa, as with the rest of Honduras, experienced significant damage by Hurricane Mitch in late-October and early-November 1998, something of a magnitude Hondurans had not witnessed since Hurricane Fifi. Mitch destroyed part of the Comayagüela section of the city, as well as other places along the banks of the Choluteca River. The storm remained over Honduran territory for five days, dumping heavy rainfall late in the rainy season. The ground was already saturated and could not absorb the heavy precipitation, while deforestation and debris left by the hurricane led to catastrophic flooding throughout widespread regions of the country, especially in Tegucigalpa.[80]

The heavy rain caused flash floods of Choluteca's tributaries, and the swollen river overflowed its banks, tearing down entire neighborhoods and bridges across the ravaged city. The rainfall also triggered massive landslides around El Berrinche Hill, close to the downtown area. These landslides destroyed most of the Soto neighborhood, and debris flowed into the river, forming a dam. The dam clogged the waters of the river and many of the low-lying areas of Comayagüela were submerged; historic buildings located along Calle Real were either completely destroyed or so badly damaged that repair was futile.[81]

Cityscape

Situated in a valley and surrounded by mountain ranges, Tegucigalpa is hilly with several elevations and few flat areas. The city is also highly disorganized, particularly around its oldest districts.[82][83][84] It has seen a rapid growth in the last 30 years,[85] and only until recently has the government passed certain laws to establish city planning and zoning rules.[86] Surface roads can be narrow with the most important avenues carrying no more than two or three lanes running in each direction, adding to the problem of heavy traffic congestion. Several of the main boulevards have been equipped with interchanges, overpasses and underpasses, allowing for sections of controlled-access highways, but considering that even the city's beltway does not entirely circle the city, the roads are generally limited-access. Intense webs of electrical and telephone lines above the streets are a common sight in the capital, and in virtually all Honduran cities, since implementation of underground utility lines has only been adopted in recent years.

Around the city

The metropolitan area of Tegucigalpa and Comayagüela is officially divided into barrios and colonias and there are 892 of them. Colonias represent relatively recent 20th-century middle class residential suburbs, some known as residenciales for their upper income development, and these are continuously spreading while the barrios are old inner-city neighborhoods.

While the city administration divides the capital into barrios and colonias, the fact that there are hundreds of them makes it difficult to define the city's different regions, especially for those not familiar with the Central District. To have a better understanding of the city's regions, the metro area of the Central District can essentially be divided, first, into two sections: Tegucigalpa and Comayagüela. These two entities remain separated by the Choluteca River basin that runs between them.

The Tegucigalpa side of the District can be divided into five sections: 1) Centro Histórico (Historic Downtown); 2) Centro Contemporáneo or Zona Viva (Contemporary Downtown or Vibrant Zone); 3) North Tegucigalpa; 4) South Tegucigalpa; and 5) East Tegucigalpa.

- 1 – Centro Histórico or the Historic Downtown of Tegucigalpa is formed by the original neighborhoods that date back to its founding days. For years, this area remained neglected and run down, but in recent times attempts have been made to revive the zone and bring back its colonial heritage. Several government offices, including the National Congress and City Hall as well as museums, parks, a cathedral and churches are located here.

- 2 – Centro Contemporáneo is the contemporary, vibrant and modern downtown of Tegucigalpa. This area is formed by the neighborhoods encompassed east of the Choluteca River, south of the northern tributary, Rio Chiquito (which confluences with the Choluteca below the Mallol Bridge), west of the beltway (Anillo Periférico), and north of Armed Forces Blvd.

This section of the city is perhaps the best developed and properly urbanized. It is formed by more than 40 neighborhoods, many of them wealthy middle class residential areas such as Colonia Palmira to the east of the historic center, on Boulevard Morazán, which hosts several foreign embassies as well as upscale restaurants. Other upscale neighborhoods are Lomas del Guijarro, Loma Linda, and Lomas del Mayab, which house most of the apartment complexes in the city.

The leading hotels of the city are found around these neighborhoods, including within the Plaza San Martín Hotel District. These include: the Marriott Hotel, Clarion Hotel, Hotel El Centenario, Intercontinental, Honduras Maya, Plaza Del Libertador, Plaza San Martín, Hotel Alameda, and Excelsior Hotel and Casino.[87][88]

Boulevard Morazán and Avenida Los Próceres/Avenida La Paz are busy commercial corridors (running parallel to each other) and run through several neighborhoods home to foreign embassies, a hotel district, business establishments and corporate buildings, including Los Próceres Comercial Park (Parque Comercial). Boulevard Suyapa and Boulevard Juan Pablo II are located south of the aforementioned boulevards, and they also form a busy commercial and financial district stretching through several neighborhoods such as Colonia Los Profesionales where the Presidential House is located; Colonia Florencia Norte where Multiplaza Mall is located; Colonia Miramontes, among others—housing several financial institutions, government offices, hotels, etc.

- 3 – North Tegucigalpa is formed by both middle class and impoverished neighborhoods that lie above the surrounding hill immediately north of the historic downtown. Beyond these neighborhoods sits the United Nations National Park on El Picacho Hill, one of the most popular destinations in the capital among its residents and visitors. Beyond the Park, stretching north and northwest of the city, upper income suburban neighborhoods such as El Hatillo sit on the sides of the hills, surrounded by heavy vegetation.

- 4 – South Tegucigalpa is everything south of Boulevard Fuerzas Armadas. This area is home to Colonia Kennedy, the capital's largest neighborhood with more than 137,000 residents. South Tegucigalpa concentrates both middle class and poor neighborhoods. Two universities, UTH and UNITEC, are located just off the beltway in southern outskirt neighborhoods.

- 5 – East Tegucigalpa concentrates mostly rural and impoverished neighborhoods, the result of improvised growth with little government funding and involvement. María Pediatric Hospital and the Basílica of Suyapa lie on the side of Anillo Períferico's eastern stretch.

Comayagüela

Comayagüela is found on the west bank of the Choluteca River, and most of its urbanization is made up of lower income neighborhoods. Historically, Comayagüela has remained less developed than the other side of the capital, some citing insufficient contribution from public officials. In recent years, this western side of the capital has seen some growth and improvement such as the opening of Metromall near the airport. With the construction of Mall Premier and City Mall, the latter to become the largest mall in the country, Comayagüela will be receiving another upgrade. There are an estimated 650,000 residents in Comayagüela contributing 58.3 percent of the 120 million lempiras (US$6.349 million) generated every day by commerce in the Central District.

The Comayagüela side of the capital can be divided into four sections: 1) Zona Centro (Downtown Comayagüela); 2) North Comayagüela; 3) South Comayagüela; and 4) West Comayagüela:

- 1 – Zona Centro de Comayagüela is the downtown area of Comayagüela and also the original founding grounds formed by its oldest barrios. These barrios are formed in a grid street plan style. Several government offices are located in this district, including the Central Bank of Honduras Annex building and the Criminal Bureau of Investigation (Dirección General de Investigación Criminal) as well as the National School of Fine Arts housed in the former City Hall building of Comayagüela, built in 1845.

- 2 – North Comayagüela is formed by relatively recent post-Hurricane Mitch middle class residential developments that stretch onto the northern hills of Comayagüela, such as Colonia Cerro Grande, a continuously growing middle-class neighborhood on the northern outskirts.

- 3 – South Comayagüela is by far the better-off region of Comayagüela. This area is found south and southwest of the airport, around Los Laureles Reservoir and south of Lepaterique Road (Carretera Lepaterique also known as Carretera al Batallón). Also a post-Hurricane Mitch area, it has grown in the last decade and includes some of Comayagüela's upper income communities that have erupted in the area and continues to spread out as newer suburban middle class developments are built. Toncontín International, Metro Mall and City Mall are located in this area. Residencial la Arboleda and Residencial los Hidalgos are some of the growing upper income developments in the southern outskirts of Comayagüela.

- 4 – West Comayagüela is mostly impoverished neighborhoods spreading away from Zona Centro onto the surrounding slopes. Many of these neighborhoods came to be through improvised urbanization and lack proper infrastructure. This area prevails north of Lepaterique Road and westward of Boulevard de la Comunidad Europea (European Community Blvd).

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1791 | 5,431 | — |

| 1801 | 6,547 | +20.5% |

| 1881 | 17,309 | +164.4% |

| 1887 | 17,647 | +2.0% |

| 1895 | 17,300 | −2.0% |

| 1901 | 24,000 | +38.7% |

| 1961 | 164,941 | +587.3% |

| 1974 | 302,483 | +83.4% |

| 1988 | 595,931 | +97.0% |

| 2001 | 850,445 | +42.7% |

| 2004 | 874,515 | +2.8% |

| 2006 | 920,366 | +5.2% |

| 2010 | 1,126,534 | +22.4% |

| 2013 | 1,157,509 | +2.7% |

| sources:[89][90][4] | ||

The 2013 Honduran census recorded a population of 1,157,509 in the Central District,[4] continuing a trend of population growth in the city since the 2001 census, which recorded 850,445 residents.[91]

In 2004, there were 185,577 households with an average of 4.9 members per household.[92] Both the city's population and metro area are expected to double by 2029.[93]

The Human Development Index (HDI) is the highest in the country measured at 0.759 in 2006. During the same year, 47.6 percent of the Central District's population lived in poverty—29.7 lived in moderate poverty and 17.9 in extreme poverty. Life expectancy in the District as of 2004 is 72.1 years. By 2010, 4.9 percent of the population remained illiterate, compared to the national rate of 15.2 percent.[94]

In 2010, the average monthly income was L.8,321 (US$440.49), compared to the total national average of L.4,767 (US$252.35) and the national urban zone average of L.7,101 (US$375.91).[95][96]

The ethnic and racial makeup of Tegucigalpa is strongly tied to the rest of Honduras.[97] 90 percent of the city-dwellers are predominantly mestizos with a small White-Hispanic minority. They are joined by Chinese[98] and Arab immigrants,[99] the latter mostly from Palestine.[100] There are indigenous Amerindians and Afro-Honduran people as well.

Tegucigalpa by numbers:[101] 4 theaters, 12 marketplaces, 12 pedestrian bridges, 12 universities, 14 hospitals, 14 museums, 28 supermarkets, 40 movie screens, 64 health centers, 64 signal light-controlled intersections, 87 middle school and high schools, 100 pharmacies, 123 local emergency committees, 170 restaurants, 200 parks or plazas, 200 sports facilities, 400 firemen, 600 volunteer workers, 892 neighborhoods classified as barrios and colonias, 12 hundred physicians, two thousand public transportation vehicles, 12 thousand taxis, 60 thousand unable to read or write, and only 140 thousand with direct access to potable water.

| Ages | Male % | Female % | Ages | Male % | Female % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80+ | 0.4 | 0.5 | 35–39 | 2.9 | 3.4 |

| 75–79 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 30–34 | 3.4 | 3.8 |

| 70–74 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 25–29 | 3.9 | 4.4 |

| 65–70 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 20–24 | 5.1 | 5.9 |

| 60–64 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 15–19 | 5.5 | 6.2 |

| 55–60 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 10–14 | 5.7 | 5.7 |

| 50–54 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 5–9 | 5.9 | 5.7 |

| 45–49 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 0–4 | 5.8 | 5.5 |

| 40–45 | 2.6 | 2.9 |

Health

In 2004, there were 67 public health care establishments in the Central District—five national hospitals, 22 health centers in the metropolitan area, 37 health centers throughout the rural areas, and three peripheral clinics. There are several private hospitals in the city as well as hospitals run by the Honduran Social Security Institute (IHSS), the country's government-sponsored social insurance program.

In 2003, only 58.5 percent of the employed population contributed to IHSS while the rest who remain uninsured were attributed to being employed in the informal sector or being domestic workers. Overall, only 26.5 percent of the Central District's population is covered by public health care.

The Central District reports the third highest or 20.2 percent of the country's HIV/AIDS incidence with 5,674 living with the virus. During 2004, there were 258 new diagnoses of HIV infection in the Central District.

In 2000, the maternal mortality rate in the city was 110 of every 100,000 births of which 62.3 percent were women ages 20 to 35. In 2001, the infant mortality rate was 29 per 1000 live births (Both maternal and infant mortality rates are based on local and out-of-district residents who arrive to receive medical attention). In 2005, it was estimated that 101 of every 10,000 residents suffered from a physical or mental disability.

Honduras in general has not had any stable medical care, the reasons being there is a lack of political stability and 62.8% of the country is in poverty and there is a lack of medical caretakers, or proper training for the caretakers, in the country.[102]

Religion

As with the rest of Honduras, Roman Catholicism is the dominating religion in the Central District and while at some point they made up as much as 95 percent of the population, contemporary estimates as recent as 2007 put them at 47 percent while Protestants make up as much as 36 percent. Their history in Tegucigalpa began around 1548 with the Spanish setting up Mercedarian missionaries as part of their conversion efforts of the native communities. By 1916, the Diocese of Comayagua was relocated and renamed the Diocese of Tegucigalpa, and it was elevated to Archdiocese under Archbishop Santiago María Martínez y Cabanas (1842–1921).[103]

Other religious groups made their way at the beginning of the 20th century including the Quakers, who in 1914 began work in the nation's capital. In 1946, missionaries of the Southern Baptist Convention first arrived in Tegucigalpa and in the 1950s, the National Convention of Baptist Churches and the Eastern Mennonite Board of Missions followed.[103]

| Central District crime indicators* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | ||

| Homicide rate | 58.1 | 60.6 | 71.8 | |

| Intentional homicides | 621 | 654 | 792 | |

| Unintentional homicides | 93 | 100 | 151 | |

| Male victim ratio | 89.7% | 91% | 91% | |

| Top victim age group (15–39) | 68.9% | 65.5% | 73.2% | |

| Firearm involvement | 80% | 81% | 85.6% | |

| Organized crime involvement | 14.2% | 26.3% | 39% | |

| Sexual assaults | 577 | 521 | 647 | |

| Crimes against person | 3,791 | 3,746 | 4,471 | |

| Crimes against property | 659 | 3,406 | 7,863 | |

| Suicides | 72 | 64 | 69 | |

| Top suicide age group (15–39) | 48.6% | 35.9% | 47.8% | |

| Vehicle-related deaths | 222 | 235 | 246 | |

| *Data based on crimes reported to authorities. Source:[104][105][106] | ||||

The Assembly of God missionaries entered Honduras in the late 1940s and today maintain a mega-church in Tegucigalpa with more than 10,000 members. The Church of God of Cleveland, Tennessee was established in Tegucigalpa in 1951, the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel followed in 1952, and by the late 1950s, the Evangelical Alliance of Honduras was established. The Prince of Peace Pentecostal Church, founded in Guatemala City, began its ministry in Honduras during the 1960s. During the 1970s, the Catholic Charismatic Renewal Movement began to grow among the upper classes in Tegucigalpa.[103]

The Christian Love Brigade Association arrived in Tegucigalpa in 1971, the Abundant Life Christian Church was founded in 1972, the Cenacle Christian Center of Charismatic Renewal began in 1978 and the Living Love Groups started in 1978.[103]

The Presbyterian Church in Honduras member churches are mainly concentrated within 150 km (93 mi) of Tegucigalpa. The first Presbyterian congregation was planted 50 years ago, by the National Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Guatemala.[107]

Today, they are many religious groups in Tegucigalpa including a Jewish community, Jehovah's Witnesses and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that is building a new temple in the city.[103]

Crime and violence

Honduras, including the capital city Tegucigalpa, has the world's highest murder rate.[108] Honduras has been experiencing record-high violence in recent years. In 2010, the homicide rate in Francisco Morazán was 83.2 (per 100,000 inhabitants) compared to the national average of 86.[109]

In 2009, the Central District reached a homicide rate of 72.7 with authorities recording 792 intentional homicides and 151 involuntary homicides; this averaged to 66 murders per month or two per day. 85.6 percent of the deaths were committed by firearm and 39 percent were linked to organized crime. 91 percent of the victims were men and 81.2 of that were ages 15 to 39. The neighborhoods in Tegucigalpa reporting the highest incidence of violent deaths are poor and impoverished areas that include Barrio Concepción, Colonia Nueva Capital, Colonia Villa Nueva Norte, Colonia Cerro Grande, Colonia El Carrizal No. 1, Colonia el Carrizal No. 2, Colonia Flor Del Campo, Colonia La Sosa, Colonia Las Brisas, and Barrio Centro de Comayagüela.[106]

In 2009, there were 246 motor vehicle-related deaths, of which 52 percent were pedestrians, including bicyclists; 39 percent were caused by private vehicle and 12 percent by public transportation vehicle. In the same year, there were 69 deaths reported as suicides, which were most common in the age bracket of 20 to 29 and 30 to 35, while 76.9 percent of them were men.[106]

Having around eight million people in the country, Honduras has about 7,000 gang members in 300 to 400 street gangs, most of them based in Tegucigalpa. These gangs commit all types of crimes against the local population as well as foreigners, including phone call threats. The gangs also appear to have a lot of control in the cities with controlling public goods such as public taxis and they are very involved. The Honduran government does not have much control against the gangs because the government system is not itself very stable. Most of the crime cases are not very well prosecuted and sometimes just discarded, but police enforcement is better in the upper-class neighborhoods and in the tourists parts of the city.[110]

Economy

The Central District has an economy equal to 19.3 percent of country's GDP. In 2009, the city's revenue and expenditures budget was L.2,856,439,263 (US$151,214,182)[111] while in 2010 it was L.2,366,993,208 (US$125,204,606).[112][113] 57.9 percent or L.43.860 billion (US$2.318 billion) of the country's national budget is spent within the Central District.[114]

The District's active labor force is 367,844 people of which 56,035 are employed in the public sector. In 2009, the unemployment rate in Tegucigalpa was 8.1 percent,[115] and an unemployed person may spend as much as four months seeking employment.[116] There are 32,665 business establishments throughout the capital, the most of any city in the country. The size of these businesses is broken down as follows: micro-enterprises (73.2%), small businesses (9.63%), medium-sized businesses (7.47%), large companies (0.28%), and the remainder unreported (9.62%).

The city's major economic sources are commerce, construction, services, textiles, sugar, and tobacco.[117] Economic activity is broken down as follows: commerce—including wholesale, retail, auto repair, household goods (42.86%); manufacturing industry (16.13%), hospitality—hotels and restaurants (14.43%), banking and real estate (10.12%), social and personal services (8.94%), health-related services (3.90%), and others (3.60%).[118]

The industrial production taking place in the region includes textiles, clothing, sugar, cigarettes, lumber, plywood, paper, ceramics, cement, glass, metalwork, plastics, chemicals, tires, electrical appliances, and farm machinery. Maquiladora duty-free assembly plants have been established in an industrial park in the Amarateca valley, on the northern highway.[119] Silver, lead and zinc are still mined in the outskirts of the city.[120]

Banking

Honduran banks based in Tegucigalpa include the Central Bank of Honduras, Banco Continental and Banco de Occidente. Tegucigalpa also has a number of International financial institutions, which include BAC Credomatic (formerly Banco Mercantil-BAMER), Citibank, Davivienda, the Inter-American Development Bank (IAB), the World Bank, and the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (BCIE), with its headquarters located in Colonia Miramontes on Boulevard Suyapa.[121]

Foreign investment

Manufacturing assembly plants (maquiladoras) were introduced in Honduras in 1976.[122] While their contribution to the economy remained small, they boomed at the beginning of the 1990s, mostly concentrating in northern Honduras, but after the mid-1990s they were expanded to the central region, including Tegucigalpa. By 2005, at least 6 maquiladoras operated in the Central District.[123]

By the end of the 1990s and early 2000s (decade), Tegucigalpa continued to be a focus city for the development of industrial parks. The main obstacle to establishing factories in Tegucigalpa has been facilitating infrastructure to provide efficient access between the capital and country's economic hubs: San Pedro Sula and Puerto Cortez.[124]

While foreign investment manufacturers and exporters have focused on northern Honduras, the presence of multinational corporations is evident in Tegucigalpa. Popular retail, restaurant, and hospitality American-branded franchises prevail throughout the Honduran capital; such as Walmart, McDonald's, and Marriott, among others. Companies from other countries such as Mexico, have also made their presence with arrivals like Cinépolis movie theaters, which opened in 2010 in Cascadas Mall.[125] Foreign real estate and property developers operate in the capital District as well, such as Grupo Roble of the Multiplaza malls.

Tegucigalpa's economic challenges are tied to those of the rest of the country, such as overcoming crime, anomalies in the judicial system, educational backwardness, and deficient infrastructure in order to continue to encourage foreign investors and permit growth of local entrepreneurs.[126]

Government

As capital of Honduras, as department head and as a municipality, the Central District seats three separate governments: national, departmental and municipal.[127] Prior to 1991, the central government held great jurisdiction over the execution of city management across the country, leading to uneven representation and improper distribution of resources and governance.[128] As a result, in late 1990 under Decree 134-90, the National Congress of Honduras enacted the Law of Municipalities (Ley de Municipalidades), defining the country's department and municipal institutions, representatives and their functions to give city government autonomy and decentralize it from the national government.[129]

While autonomous, the Central District is still influenced by the national government given the territory remains seat of government of the republic. Major changes in public policy and funding of major city projects usually reach the Office of the President prior to approval by the District's local government.[130]

The government in Honduras is very unstable, the government has a very hard time providing the proper resources for citizens and forming their citizens in investing in medical equipment and education for medical professions in Honduras, they also have difficulties with controlling the criminals in cities and gangs that resulted in such high crime rates in the country.[102][131]

Central District

Legally and politically speaking, the capital of Honduras is the Municipality of the Central District (Spanish: Distrito Central or DC) and Tegucigalpa and Comayagüela are two entities within the district. However, nearly all governmental institutions are on the Tegucigalpa side, so for all practical purposes Tegucigalpa is the capital.[15] Traditionally, they are regarded as twin or sister cities in part because they were founded as two distinct cities.[132] When the Central District was formed on January 30, 1937 under Decree 53 of reformed Article 179 of the 1936 Honduran Constitution, both cities became one political entity sharing the title of Capital of Honduras.[20]

The Constitution of Honduras, under Chapter 1, Article 8, states (translated), "The cities of Tegucigalpa and Comayagüela, jointly, constitute the Capital of the Republic."[18] Furthermore, Chapter 11, Article 295, states (translated) "The Central District consists of a single municipality made up of the former municipalities of Tegucigalpa and Comayagüela";[19] however, municipalities in Honduras are defined as political entities similar to counties, and they may contain one or more cities. For example, in the Department of Atlántida, La Ceiba is the largest city—being also the third largest in Honduras—both in terms of population and metropolitan area;[133] however, Tela, one of the eight municipalities of Atlántida, is the biggest municipality in terms of physical administrative area in that department.[134] Since the Municipality of Tela is not considered the entire city of Tela, it is not bigger than La Ceiba.

There are an additional of 41 villages and 293 hamlets through the Central District Municipality.[5] These may be assigned deputy mayors (alcalde auxiliar) to serve as local representatives.

National and departmental governments

Tegucigalpa is the political and administrative center of Honduras.[135] It is also the seat of government of the Francisco Morazán department.[136] All three branches of the national government as well as their immediate divisions—including the 16 departments of the Executive Branch,[137] the National Congress,[138] the Supreme Court of Justice,[139] the Armed Forces and National Police headquarters—are located in the city. Most public agencies and state-owned companies are headquartered in the capital as well.[26]

Local government

City government takes the form of a mayor-council system and is regulated under the Law of Municipalities that came into effect on January 1, 1991. The Central District Municipal Government (Alcaldía Municipal del Distrito Central or AMDC) is the city's governing authority. As established by city governing law, AMDC is structured as a municipal corporation, which is the deliberative-legislative body, voter-elected, and highest authority within the municipality.[140]

The Municipal Corporation is formed by a mayor serving as chief executive, general administrator and legal representative of the municipality[141] and a vice mayor to serve as acting mayor when required and to oversee functions within AMDC as instructed by the mayor.[142]

Ten aldermen (regidores) are also members of the Municipal Corporation who along with the mayor execute the duties as described in the Law of Municipalities, including management, budgeting, and local law and ordinance legislation.[143]

A general manager, appointed by the mayor, serves as chief comptroller to manage city funds and their allocation. A municipal secretary, also appointed by the mayor, serves as the city clerk in charge of keeping record of all official proceedings. The Municipal Corporation also consults with a Municipal Development Council (Consejo de Desarrollo Municipal), which serves as an advising cabinet on all the areas of issues of the city such as human development, public safety, utilities, etc.[144]

Current administration

The mayor of the Central District is Nasry Asfura (PNH)[145] who is serving his second term (2018–2022) after being reelected in 2017.[146] He is the eighth person to serve as mayor of the Central District since local elections were restored in 1986 (prior to 1986, the Central District local government, known as Consejo Metropolitano (Metropolitan Council), was appointed by the President); and this is the ninth elected mayoral term since then and the fourth consecutive elected mayor from the National Party.

Of the 10 aldermen serving, seven are men and three are women. Five belong to the National Party while another two belong to Libertad y Refundación; two aldermen belong to the Liberal Party and the other is from the Anti-Corruption Party.

Both the city mayor and aldermen are elected to 4-year terms by voters of the Central District. Removal of the mayor or any alderman for any cause is reserved to the Ministry of Interior and Population (Secretaría del Interior y Población), formerly Secretaría de Gobernación y Justicia.[147]

Law enforcement

Law enforcement in the city is the responsibility of the National Police of Honduras, the nationwide police force.[148][149] The National Police maintains its headquarters in the Central District in Colonia Casamata. The Metropolitan Police Headquarters No. 1 (Jefatura Metropolitana No. 1) is the police department in charge of law and order in the city. It operates seven police districts throughout the metropolitan area. These are Police District 1-1 El Edén, Police District 1–2 El Mandén, Police District 1–3 San Miguel, Police District 1–4 Kennedy, Police District 1–5 El Belén, Police District 1–6 La Granja and Police District 1–7 San Francisco. For 2011, the Secretary of Security designated L.2.162 billion (US$114.283 million) to law enforcement and criminal investigation in the Central District.

As established by the Law on Police and Social Coexistence (Ley de Policía y Convivencia Social), municipalities can fund their own municipal police (Policía Municipal) and the Central District operates a Municipal Police force of 160 officers. The Municipal Department of Justice (Departamento Municipal de Justicia) through its Municipal Police Court (Juzgado de Policía Municipal) enforces and prosecutes local law offenses.

The Public Ministry (Ministerio Público) is the district attorney with nationwide jurisdiction in charge of prosecuting crimes on behalf of the people. It is also headquartered in the Central District and maintains regional prosecution offices throughout the country. The Attorney General of the Republic (Procuraduría General de la República) is the country's chief legal representative and prosecutes crimes on behalf of the state.[150]

Education

Tegucigalpa serves as the national education center, hosting most of the universities and higher education institutions in the country. For 2011, the national government allocated L. 9.175 billion (US$484.9 million) of the national public education budget (equal to 42.1 percent of total) to the Central District.

The public and private education system in Tegucigalpa is divided into 16 school districts (distritales).[151] All districts are part of the Departmental Directorate of Education (Dirección Departamental de Educación), which in turn is a part of the country's Secretary of Education.[152]

There are 1,235 public schools in the Central District broken down as 488 preschools, 563 elementary schools, and 184 middle and high schools. In 2003, there were a total of 287,517 students enrolled throughout the municipality—28,915 in preschool, 159,679 in elementary school, and 98,923 in middle or high school.[92] The literacy rate, as of 2011, is at 80%.

Private schools

There are about 147 bilingual schools in Tegucigalpa.[153] The American School of Tegucigalpa (K-12), Discovery School (K-12), DelCampo International School (K-12), La Estancia School (K-11) and International School of Tegucigalpa (K-12, Christian) are considered the most expensive private schools of the city. Total K-12 tuition of The American School of Tegucigalpa costs a total of L.1.366 million (US$72,248) for all years (amount based on 10–11 academic year). These private schools are highly recognized by American institutions such as the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS-CASI) and the American School of Tegucigalpa is the only one that has the International Baccalaureate (IB Program). Most of their students study abroad. Other popular private/bilingual schools include Elvel School (K-11), Dowal School (K-11, secular), La Estancia School (K-11), Shadai School (K-11, Christian), Lycée Franco-Hondurien (K-12, French), Magic Castle Preschool (K), Macris School (E-HS, Catholic), and ABC Educational Center (N-8avo, Christian).

There are two modalities in regards to the school calendar: American Period (August to July), mostly used by private and bilingual schools; and Latin Period (February to November), used by public schools.[154]

Universities

There are 12 universities in Tegucigalpa, including three state-funded higher education institutions.[155]

The National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH), founded in 1847, is the country's most important university and operates eight regional campuses in several other cities in the country: UNAH-Valle de Sula, UNAH-La Ceiba, UNAH-Comayagua, UNAH-Copán, UNAH-Choluteca, UNAH-Juticalpa, UNAH-Valle del Aguán, and University Technological Center UNAH–Danlí.[156] It employs 4,980 people throughout its campuses at an average annual salary of L.241,184 (US$12,747).

The other two publicly funded institutions are Francisco Morazán National Pedagogic University (UPNFM), founded in 1989, focusing on preparing future educators in several disciplines,[157] and the National Institute of Professional Formation (INFOP), founded in 1972, focusing on economic and social development disciplines. The National University of Agriculture (UNA), founded in 1950, also state-funded and located in Catacamas, Olancho, maintains a liaison office in Tegucigalpa.

There are 10 private universities in Tegucigalpa:

|

|

There are also two higher education centers: the Technological University Center (CEUTEC), part of UNITEC; and Guaymura University Center (CUG), founded in 1982.

Transportation

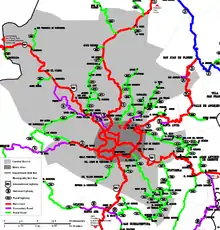

All barrios and colonias in Tegucigalpa can be accessed by automobile, although some neighborhoods in the city suffer from unpaved, narrow, or hilly streets making them difficult to maneuver.[164] A grid of surface streets and a network of major avenues and boulevards cross through the major areas of the capital. However, the most transited roads suffer from heavy traffic congestion due to the region's geography and disorganized urbanization.

An estimate of 400,000 vehicles take on the city streets and roads every day. The oldest districts were not built with the advent of the automobile in mind and therefore lack efficient roadways to accommodate the overwhelming number of vehicles. Newer developments, such as the malls, have been built with the car in mind allowing for large parking lots to accommodate their visitors. In the last decades, several of the boulevards and avenues have been retrofitted with grade separations to ease up the flow of traffic.

Roads and highways

The Secretariat of Public Works, Transport and Housing (Honduras) (SOPTRAVI) presently divides the country's highway network into international routes (ruta internacional), national routes (ruta nacional), and provincial routes (ruta vecinal). These are assigned numbers; however, they are more often identified using their physical destinations (e.g. Tegucigalpa-Danlí highway) rather the number itself since road signage is scarce.

International routes are given a "CA-" designation followed by a highway number (i.e. CA-1) that can be of one or two digits enclosed in a highway shield. "CA-" highways are part of the Central American highway network (hence the "CA" letters) that interconnects Honduras with its neighboring countries as part of the Pan-American Highway. National highways are assigned a two or three-digit number and provincial routes are assigned a three-digit number.

Arterial roads

The Anillo Periférico (beltway or ring road) and Boulevard Fuerzas Armadas (Armed Forces Blvd) are the city's two expressways—equipped with center dividers, interchanges, overpasses and underpasses—allowing for controlled-access traffic. These connect with the city's other major boulevards: Central America Blvd, Suyapa Blvd, European Community Blvd, and Kuwait Blvd—which are essentially limited-access roadways as they have been equipped with interchanges but may lack underpasses or overpasses to bypass crossing surface road traffic.

Despite a network of major highways, none reach directly into the historic downtown, forcing drivers to rely heavily on surface streets. Like in most Central American cities, orientation and driving may be difficult to first-time visitors due to the nature of how streets are named, insufficient road signage and the natives' driving behavior.[165] The city administration has green lit several road infrastructure projects to help reduce traffic congestion and improve the overall aspect of the city.[166]

List of major thoroughfares in the Central District, including urban core arteries and outskirt roads:

|

International highways

|

National highways

|

Rural highways

|

City highways

|

Major roads and streets

|

Public transportation

Public transportation in Tegucigalpa and Comayagüela is based on buses and taxis, covering 71 percent of the capital's road migration. Bus routes are named based on the neighborhood they cover. For example, routes that travel from the downtown area to UNAH are labeled Centro-UNAH or Centro-Multiplaza-UNAH. Taxis are the quickest way to move around the city after personal auto transportation. Taxis are popular for short-distance trips or trips that require a sense of urgency. Taxis are relatively cheap for the international tourist. They are not the cheapest form of public transportation for the locals, however. There are over 12,000 taxis in the Central District.

The public transportation system in Tegucigalpa is, however, highly disorganized.[167] Being a for-profit business, it encourages competition between the fleet owners where revenue is the priority while ignoring the quality and efficiency of the service. Public transportation regulation is very flawed. Bus drivers must compete for passengers in order to bring the highest earnings possible while becoming a hazard for other drivers and pedestrians and contributing to traffic jams.[168] There is an overflow of public transportation vehicles on the roads.[169] The government has declared its public transportation system to be oversupplied and inefficient.[168]

There is a project under construction to give the public transportation system an upgrade with the addition of a bus rapid transit fleet. In late May 2011, the National Congress approved the project under a new law as part of the financing deal with the Inter-American Development Bank (IAB). The BRT system will be solely managed by the Central District government.

National and international ground transportation

Tegucigalpa is connected with the rest of the country through its city to city bus services. There are several bus lines connecting the capital with the rest of Honduras.[170] There is no central bus terminal in the city; in turn, there are several bus stations scattered throughout the city, particularly in Comayagüela, and some of these stations are operated directly by the bus company serving from there. Tegucigalpa is connected with the rest of Central America and Mexico through its international bus lines. Buses leave for Guatemala, El Salvador,[171] Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama and Mexico every day.[172][173]

Air transportation

Toncontín International Airport (IATA: TGU, ICAO: MHTG), serves as the main airport in and out of Tegucigalpa. It is served by three domestic airlines and six international airlines connecting the capital to three cities in the United States and four cities in Central America as well as four cities within Honduras.[174]

The airport is frequently criticized as being dangerous; due to its location next to a sierra, short runway, and difficult approach. Large commercial jets are required to execute a tight hairpin left turn at very low altitude to land on the short runway. International airline pilots flying into Toncontín receive additional training for the Toncontín approach.

Toncontín has been improved by the work of the Airport Corporation of Tegucigalpa (CAT), which is owned by TACA of El Salvador. It is managed by InterAirports, the company hired by the government of Honduras to manage the four airports in the country.[175]

The airport authority and the government of Honduras resumed airport relocation talks in April 2011 and announced that work on the new Palmerola airport would start by the fall of 2011 after years of efforts to replace Toncontín International with an airport at Palmerola in Comayagua where the Soto Cano Air Base is located.[176] However, in a September 25, 2011 update, President Lobo stated officials were still "evaluating the pros and cons" of constructing the new airport.[177] This comes three years after former President Manuel Zelaya had announced that all commercial flights would be transferred to Soto Cano Air Base; however, work on the new terminal at Soto Cano was then cancelled after Zelaya was removed from office on 28 June 2009 in the 2009 Honduran coup d'état.[178] Upon realization of the Palmerola airport, international flights to and from Toncontín would continue to operate but would be limited to small aircraft.

Twin towns – sister cities

Tegucigalpa is twinned with:

|

|

Notes

- Villa de Tegucigalpa is the title given by Charles III of Spain on July 17, 1768.

- Real Villa de San Miguel de Tegucigalpa y Heredia is the title given by Alonso Fernández de Heredia, then governor of Honduras, on June 10, 1762.

- Real de Minas de San Miguel de Tegucigalpa is the title given by the Spaniards on September 29, 1578.

Definitions

^[a] Tegucigalpa refers to the urban area formed east of the Choluteca River when distinguished from Comayagüela. When broadly speaking to refer to the capital of the country, it includes Comayagüela and vice versa.

^[b] Comayagüela refers to the urban area formed west of the Choluteca River. Once a city of its own, it was incorporated as part of Tegucigalpa on September 28, 1890.

^[c] Central District refers to the entire municipality containing both Tegucigalpa and Comayagüela. As established by the Constitution of Honduras, it serves as national capital and therefore its limits as government seat are not reduced to the urban area formed by Tegucigalpa and Comayagüela but extend to the entire municipality; in turn, the Central District as a whole, is the capital of Honduras.

The Central District is not a federal district since it is not an entity outside the departments of Honduras (e.g. Washington, D.C., Mexico City); it is one of the municipalities making up the Department of Francisco Morazán.

References

- Tiroren (2008). "Meaning of word "Tegus"". tuBabel.com. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- "Enjoy your Tegucigalpa Expat Experience". InterNations.org. 2011-05-22. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- AMDC (2011-09-10). "Members of the Municipal Corporation". AMDC. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- "Distrito central: Informacion del municipio". XVII Censo de Población y VI de Vivienda 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- Mario Martin (2009-06-02). "Spanish: Urban and Environmental Complexity of Tegucigalpa" (PDF). Centro de Diseño, Arquitectura y Construcción (CEDAC). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

- Citypopulation.de Population of departments and municipalities in Honduras

- Citypopulation.de Population of departments and municipalities in Honduras

- Honducor (2008-05-10). "ZIP Codes for Honduras". Honduras.com. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- Hondutel (2009-10-14). "Honduras Country Codes". CallingCodes.org. Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- "Tegucigalpa". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- "Tegucigalpa". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- "Tegucigalpa". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- Mario Secoff (2005-03-13). "Municipality of Tegucigalpa-Distrito Central section". angelfire.com. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- "Téguz y no Tegus, algo que todos debemos saber…". vuelvealcentro.com. 2016-10-10. Retrieved 2017-01-30.

- Kiara Pacheco (2010-10-15). "Spanish:What is the capital of Honduras?". saberia.com. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- Oscar Acosta (original) (2011-02-13). "About Tegucigalpa". Emporis Corporation. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- Anonymous at the Honduras National Library (2008-05-19). "Spanish:Tegucigalpa, a particular story-pg. 3" (PDF). Francisco Morazán National Pedagogic University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-11-04. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- Government of Honduras (2001-01-31). "1982 Constitution of Honduras-Title I, Chapter I, Article 8". Honduras.net. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- Government of Honduras (2001-01-31). "1982 Constitution of Honduras-Title V, Chapter XI, Article 295". Honduras.net. Archived from the original on 2011-06-14. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- Government of Honduras (2001-02-01). "1936 Constitution of Honduras-Decree No. 53, reformed Article 179". HistoriadeHondura.hn. Archived from the original on 2014-03-24. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- BATMAN (2008-06-30). "Spanish: Department of Francisco Morazán". ecohonduras.net. Archived from the original on 2011-09-06. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- OPTURH writer (2010-03-15). "Spanish: Tegucigalpa, a city with much history". Operadores de Turismo Receptivo de Honduras. Archived from the original on 2011-10-26. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- "Spanish: Map of Francisco Morazán Department". zonu.com. 2009-05-13. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- Foundation for the Investment and Development of Exportations (FIDE) (2009-08-04). "Embassies and Consulates in Honduras". hondurasinfo.hn. Archived from the original on 2013-06-16. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- GoAbroad.com writer (2011-02-28). "Embassies in Honduras". GoAbroad.com. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- hondurasinfo.hn writer (2006-06-12). "Government Offices in Tegucigalpa". .hondurasinfo.hn. Archived from the original on 2013-06-16. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- Junta de Dirección Universitaria (2010-03-29). "National Autonomous University of Honduras". UNAH. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- FENAFUTH (2010-01-08). "Honduras National Autonomous Football Federation (FENAFUTH)". fenafuth.org. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- Ryan Bert (2001-04-29). "Difficult Approach + Short Runway = Challenge". Airliners.net. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- Jaclyn Liechti & Kate Sitarz (2010-07-31). "World's Scariest Airports". SmarterTravel.com. Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- Microsoft Flight Simulator X (2007-06-04). "Tegucigalpa's Toncontín". SimTours.net. Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- Juan Diego Zelaya; Vice Mayor (June 2010). "AMDC Organization Chart" (PDF). AMDC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- AMDC (2008-10-24). "Central District Mayor". AMDC Transparencia. Archived from the original on 2011-10-28. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- AMDC (2008-10-24). "Central District Municipal Corporation". AMDC Transparencia. Archived from the original on 2011-10-28. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- Alcaldia Municipal del Distrito Central (2008-02-12). "Spanish:Tegucigalpa City Hall approves budget of 1.555 billion lempiras for 2008". Hondudiario.com. Archived from the original on 2012-01-29. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- El Nuevo Herald (2009-09-30). "Spanish:Tegucigalpa reaches 431st birthday in tension". zonadenoticias.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-26. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- Karla Gomez (2011-05-09). "Spanish: Zoning laws do not impede businesses invading residential zones". El Heraldo de Honduras. Archived from the original on 2014-09-20. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- El Nuevo Herald (2009-09-30). "Spanish:Tegucigalpa with high-risk zones for construction". zonadenoticias.com. Archived from the original on 2013-06-04. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- Reducing Risks of Landslides and Earthquakes-PNUD (2010-11-19). "Spanish: Unorganized growth of the city requires a 'stop'". Revista Construir. Archived from the original on 2015-02-04. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- El Heraldo editor (2011-02-24). "Spanish: Government of Honduras seeks reducing traffic". El Heraldo de Honduras. Archived from the original on 2011-02-27. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- Sheila Salgado (2011-04-27). "Spanish: BCIE grants US$46.1 million for infrastructure in Tegucigalpa". hondudiario.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-25. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- Central District Municipal Office (AMCD) (2008-09-25). "Spanish: Capital450-the city we want!". AMCD. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- Eric Schwimmer (2003-02-24). "Dictionary of Honduran Colloquialisms, Idioms and Slang". geocities.ws. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- Leticia de Oyuela (1989). Historia Mínima de Tegucigalpa. Honduras: Editorial Guaymuras. ISBN 978-99926-15-92-8. OL 1971859M.

- Tegus.info writer (2003-05-07). "History of Tegucigalpa". Tegus.info. Archived from the original on 2011-02-19. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- Coordinación de Registro e Inventario de Bienes Culturales (2011-03-03). "Spanish: Danza de Los Emplumados". Comunidad Educativa de CentroAmérica y República Dominicana. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- Nahuatl translator (2008-03-09). "Náhuatl translations-meaning of Tegucigalpa". Vocabulario.com.mx. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- Michael Swanton (2009-10-28). "Nahuatl-The meaning of Tegucigalpa". Foundation of the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies (FAMSI). Archived from the original on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- Mario Secoff (2006-09-19). "Spanish: History of Tegucigalpa". angelfire.com. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- Mario Perez (2007-12-12). "Spanish: Tegucigalpa and her History". HondurasHoy.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- Crecimiento Urbano (2011-05-14). "Spanish: History of Tegucigalpa, 1740–1821 period, 4th paragraph". hondurasurbana.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- Mario Secoff (2006-09-19). "Spanish: Municipality of Tegucigalpa". angelfire.com. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- Mario Secoff (2006-09-19). "Spanish: History of the Mallol Bridge". angelfire.com. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- Crecimiento Urbano (2011-05-14). "Spanish: History of Tegucigalpa, 1578–1740 period". hondurasurbana.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- Mario Secoff (2002-02-11). "Spanish: History of Cedros, third paragraph". angelfire.com. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- Larissa Murillo (2010-04-29). "Spanish: History of Comayagua, intro paragraph". larissamurillo.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- Mario Secoff (2006-09-19). "Spanish: Municipality of Tegucigalpa, 14th & 15th paragraphs". angelfire.com. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- ahrbom (2007-11-29). "Spanish: Historical Background of Departments and Municipalities of Honduras, Decree No. 161 (COMAYAGÜELA)". monografias.com. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- Crecimiento Urbano (2011-05-14). "Spanish: History of Tegucigalpa, 1933–1961 period". hondurasurbana.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- Crecimiento Urbano (2011-05-14). "Spanish: History of Tegucigalpa, 1975–1998 period". hondurasurbana.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- Marilyn Mendez (2010-08-16). "Spanish: 128 barrios and colonias of the capital in grave risk". La Prensa de Honduras. Archived from the original on 2012-04-06. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- Edwin L. Harp, Mario Castañeda and Matthew D. Held (2002-08-04). "Spanish: Landslides provoked by Hurricane Mitch in Tegucigalpa" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- Donna DeCesare (2010-03-23). "Spanish: Hurricane Mitch devastates Honduras". Destiny's Children. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- La Prensa Editor (2010-10-26). "Spanish: 130,000 families in risk due to weather in Tegucigalpa". La Prensa de Honduras. Archived from the original on 2012-04-06. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- La Tribuna Editor (2009-10-25). "Spanish: 13 years after Mitch, the prints are still fresh". La Tribuna de Honduras. Archived from the original on 2011-11-05. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- Crecimiento Urbano (2011-05-14). "Spanish: History of Tegucigalpa, 2010–2011 period". hondurasurbana.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- Japan International Cooperation Agency (2011-01-13). "Spanish:HONDURAS-Geological faults identified in Tegucigalpa". TierraAmérica. Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

- Psychology Class at the UNAH (2010-07-30). "Spanish: Recorrido Morazanico". National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH)-PsicologíaEducativa.net. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

- Antonio Carias (2010-10-19). "Spanish:Land and Geographic Information Technologies" (PDF). National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

- El Heraldo editor (2010-05-30). "Spanish: Choluteca River flooded markets and collapsed streams in Tegucigalpa". El Heraldo de Honduras. Archived from the original on 2010-06-03. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- A. Velazco (2005-10-20). "Spanish: Descriptions of Reservoirs in Honduras" (PDF). International Regional Organization for Agricultural Health (OIRSA). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-28. Retrieved 2011-07-20.

- FNPP-Honduras, ENF (2007-01-22). "Spanish: Villa de San Antonio, Comayagua-pg. 7, geographic location" (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO-UN). Retrieved 2011-07-20.

- Tim Merrill (2010-08-23). "Honduras-Climate". countrystudies.us. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- "Spanish: Weather in Honduras". LosMejoresDestinos.com. 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- La Tribuna editor (2010-04-23). "Spanish: Next Tuesday will be hottest day of the year". LaTribuna.hn. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- "Honduras, When to go and Weather". lonelyplanet.com. 2010-08-23. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- "Tegucigalpa Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- "Klimatafel von Tegucigalpa (Int. Flugh.) / Honduras" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- "Station Tegucigalpa" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- Zeifer-Sistemas de Información Cultural (2002-04-11). "Spanish: Hurricane Mitch-estimate of loss and damages". historiadehonduras.hn. Archived from the original on 2011-09-17. Retrieved 2011-07-20.

- La Prensa editor (2008-10-19). "Spanish: Mitch, a Destructive Monster". LaPrensa.hn. Archived from the original on 2012-04-06. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- Agencia ACAN-EFE (2008-09-29). "Spanish: Tegucigalpa cumple 430 años entre desorden y vulnerabilidad". RadioLaPrimerisima.com. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- Carlos Arturo Matute (2011-03-12). "Spanish: Tegucigalpa- the neglected "girl" who grew disorderly". La Tribuna de Honduras. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- Agustín Lagos (2008-08-27). "Spanish: The capital grows toward the south and east". El Heraldo de Honduras. Archived from the original on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- Shlomo Angel with Katherine Bartley, Mary Derr, Anshuman Malur, James Mejía, Pallavi Nuka, Micah Perlin, Sanjiv Sahai, Michael Torrens, and Manett Vargas (2004-01-22). "Rapid Urbanization in Tegucigalpa, Honduras" (PDF). Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs-Princeton University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-23. Retrieved 2010-07-01.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Government of the Central District (2009-04-17). "Spanish: Laws and Ordinances". Central District Mayor's Office. Archived from the original on 2012-08-01. Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- Yahoo Travel (2003-08-14). "Popular Hotels in Tegucigalpa". travel.yahoo.com. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- Hotels.com L.P. (2011-04-06). "Popular Hotels in Tegucigalpa". hotels.com. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- Angel, Shlomo; Bartley, Katherine; Derr, Mary; Malur, Anshuman; Mejía, James; Nuka, Pallavi; Perlin, Micah; Sahai, Sanjiv; Torrens, Michael; and Vargas, Manett. Rapid Urbanization in Tegucigalpa, Honduras. Princeton University: Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, February 2004, 10.

- "History of Censuses" (DOC). Honduras National Statistics Institute (INE). 2010-10-19. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- Honduras National Statistics Institute (INE) (2002-06-19). "Spanish: 2001 Population (16th) and Household (5th) Census" (PDF). Central American Population Center-University of Costa Rica. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- Lic. Elsa Lili Caballero (2009-06-02). "Spanish: Social Tendencies- Current Situation and Challenges" (PDF). National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- Miriam Amaya Medina (2009-04-25). "Spanish: Tegucigalpa, a challenge for order". El Heraldo de Honduras. Archived from the original on 2009-05-03. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- Honduras National Statistics Institute (INE) (2010-10-15). "Spanish: Illiteracy Levels by May 2010". ine.gob.hn. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- Honduras National Statistics Institute (INE) (2010-10-15). "Spanish: Average Work Income by May 2010". ine.gob.hn. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- Gerencia de Estadisticas Sociales y Demografía. Ingreso Promedios por Trabajo años 2008–2010. Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE): Encuesta Permanente de Hogares de Propósitos Múltiples, Mayo 2010, pg 1.

- U.S. Library of Congress (2003-08-09). "Ethnic groups in Honduras". CountryStudies.us. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- Mario Secoff (2003-03-01). "Spanish: The Chinese in Honduras". angelfire.com. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- Mario Secoff (2003-03-01). "Spanish: Arabs in Honduras". angelfire.com. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- Amaya, José Alberto. Los Árabes y Palestinos en Honduras (1900–1950). Tegucigalpa: Guaymuras Archived 2012-03-27 at the Wayback Machine, February 1997, 157pp.

- Lourdes Barahona (2009-09-27). "Spanish: Tegucigalpa-431 years of black and white numbers". El Heraldo de Honduras. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- "Honduras Health Insurance - Pacific Prime International". www.pacificprime.com. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- Clifton L. Holland (2009-06-25). "Religion in Honduras" (PDF). prolades.com. Retrieved 2011-11-23.

- University Institute on Democracy, Peace and Security (IUDPS) – UNAH (December 2007). "Spanish: Observatory on Violence in the Central District – 2007" (PDF). iudpas.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- University Institute on Democracy, Peace and Security (IUDPS) – UNAH (February 2009). "Spanish: Observatory on Violence in the Central District – 2008" (PDF). iudpas.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- University Institute on Democracy, Peace and Security (IUDPS) – UNAH (February 2010). "Spanish: Observatory on Violence in the Central District – 2009" (PDF). iudpas.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- http://www.honduraspresbytery.com/Presbytery_of_Honduras/Welcome.html%5B%5D

- Pressly, Linda (3 May 2012). "Honduras Murders: Where Life Is Cheap and Funerals Are Free". BBC Magazine.

- United Nations Development Programme (2011-09-08). "Spanish: Comprehensive Policy of Citizen Security for Honduras" (PDF). transparencia-seguridad.gob.hn. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2011-11-23.

- "Honduras 2016 crime and safety report". www.osac.gov. 2016-03-14. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- Juan Carlos Perez Caldaso A. (2009-05-10). "Spanish: 2009 Revenue/Expenditures Budget Bill" (PDF). Central District Mayor's Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2011-09-28.