The Great Controversy (book)

The Great Controversy is a book by Ellen G. White, one of the founders of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and held in esteem as a prophetess or messenger of God among Seventh-day Adventist members. In it, White describes the "Great Controversy theme" between Jesus Christ and Satan, as played out over the millennia from its start in heaven, to its final end when the remnant who are faithful to God will be taken to heaven at the Second Advent of Christ, and the world is destroyed and recreated. Regarding the reason for writing the book, the author reported, "In this vision at Lovett's Grove (in 1858), most of the matter of the Great Controversy which I had seen ten years before, was repeated, and I was shown that I must write it out."[1]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| |

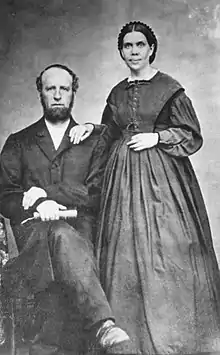

| Author | Ellen White |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Subject | History of sin from beginning to end |

| Genre | Historical, Religious |

| Publisher | James White |

Publication date | 1858 |

| Pages | 219 |

| Part of a series on |

| Seventh-day Adventist Church |

|---|

|

| Adventism |

The name "Great Controversy" first applied to volume 1 of the 4 volume set "Spiritual Gifts" published in 1858. That single volume was then expanded to a 4 volume set entitled "The Spirit of Prophecy" subtitled "The Great Controversy" with the volumes published separately from 1870 to 1884. The last volume was also subtitled, "From the Destruction of Jerusalem, to the End of the Controversy". The 4 volume set was then expanded to 5 volumes entitled "the Conflict of the Ages Series" with the last volume given the name "The Great Controversy Between Christ and Satan During the Christian Dispensation" published in 1888. Volume 5 was again expanded and published in 1911. The 1884, 1888, and 1911 books incorporate historical data from other authors.

Synopsis

This synopsis is of the current, 1911 edition. It covers just the Christian dispensation.

The book begins with a historical overview, which begins with the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70, covers the Reformation and Advent movement in detail, and culminates with a lengthy description of the end times. It also outlines several key Seventh-day Adventist doctrines, including the heavenly sanctuary, the investigative judgment and the state of the dead.[2]

Much of the first half of the book is devoted to the historical conflict between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism. White writes that the Papacy propagated a corrupt form of Christianity from the time of Constantine I onwards, and during the Middle Ages was opposed only by the Waldensians and other small groups, who preserved an authentic form of Christianity. Beginning with John Wycliffe and Jan Huss and continuing with Martin Luther, Huldrych Zwingli, and others, the Reformation led to a partial recovery of biblical truth. In the early 19th century William Miller began to preach that Jesus was about to return to earth; his movement eventually resulted in the formation of the Adventist Church.

The second half of the book is prophetic, looking to a resurgence in papal supremacy. The civil government of the United States will form a union with the Roman Catholic Church as well as with apostate Protestantism, leading to enforcement of a universal Sunday law (the mark of the beast), and a great persecution of Sabbath-keepers immediately prior to the second coming of Jesus. And these will be part of the end time remnant of believers who are faithful to God, which will be sealed and manifested just prior to the second coming of Jesus.

The official Ellen G. White Estate web site views the 1888 version as the original "Great Controversy," with the 1911 edition being the only revision.[3] The "Synopsis" and "Sources" below reflect this and do not refer at all to the 1858 version and only partially to the 1884 version.

While working to complete the book in 1884, White wrote, "I want to get it out as soon as possible, for our people need it so much.... I have been unable to sleep nights, for thinking of the important things to take place.... Great things are before us, and we want to call the people from their indifference to get ready."

In the 1911 edition preface, the author states the primary purpose of the book to be "to trace the history of the controversy in past ages, and especially so to present it as to shed a light on the fast approaching struggle of the future."[4]

Publishing and distribution

There are four major editions of the book commonly called The Great Controversy. While currently all editions printed by Seventh-day Adventist publishing houses are based on the 1911 edition, the first three editions have also been reprinted by Seventh-day Adventist publishing houses as facsimile reproductions, and several Seventh-day Adventist laymembers have reprinted them in various formats, with various titles also.

Publication history:

| Book Name[5] | Year | Chapters | Word Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual Gifts, Volume 1:

The Great Controversy between Christ and His Angels, and Satan and His Angels |

1858 | 41 | ~48,800 |

| The Spirit of Prophecy: The Great Controversy Between Christ and Satan, 4 volumes:

From the Destruction of Jerusalem, to the End of the Controversy, Volume 4 |

1884 | 37 | ~136,700 |

| The Conflict of the Ages Series, 5 volumes:

The Great Controversy Between Christ and Satan During the Christian Dispensation, Volume 5 |

1888 | 42 | ~237,400 |

| The Conflict of the Ages Series, 5 volumes:

The Great Controversy Between Christ and Satan in the Christian Dispensation, Volume 5 |

1911 | 42 | ~241,500 |

The 1858 edition

In 1858, at Lovett's Grove, Ohio, Sunday, Mid-March, a funeral was held in a schoolhouse where Ellen and James White were holding meetings, James was asked to speak and Ellen was moved to bear her testimony. Part way through her talk, she went into a two-hour vision in front of the congregation. The vision mostly concerned the matter of the "great controversy," which she had seen ten years before (1848). She was told that she must write it out. The next day on a train they began arranging plans for writing and publishing the future book immediately on their return home. At a stopover, Ellen experienced a stroke of paralysis, which made writing virtually impossible.[6]

For several weeks afterward, Ellen could not feel pressure on her hand or cold water poured on her head. At first, she wrote but one page in a day and then rested for three. But as she progressed, her strength increased, and by the time she finished the book, all effects of the stroke were gone. The book was completed by mid-August and subsequently published as Spiritual Gifts, Vol. 1,: The Great Controversy Between Christ and His Angels, and Satan and His Angels.[6]

It is written in the first-person present tense, with the phrase "I saw" being used 161 times to refer to the author's experience in receiving the vision given to enable her to write this book. The book describes the whole history of sin chronologically, from before sin ever entered the universe to after its final destruction in The New Earth.

The 1884 edition

Plans were laid in the late 1860s for the Spirit of Prophecy series, an expansion of the 1858 Great Controversy theme into four volumes, designed especially for Seventh-day Adventist reading. Volume 1, dealing with Old Testament history, was published in 1870. The New Testament history required two volumes which were published in 1877 and 1878.[7]

For volume 4, Ellen was instructed through vision to present an outline of the controversy between Christ and Satan as it developed in the Christian dispensation to prepare the mind of the reader to understand clearly the controversy going on in the present day. She explained:

"As the Spirit of God has opened to my mind the great truths of His Word, and the scenes of the past and the future, I have been bidden to make known to others that which has thus been revealed—to trace the history of the controversy in past ages, and especially so to present it as to shed a light on the fast approaching struggle of the future. The great events which have marked the progress of reform in past ages, are matters of history, well known and universally acknowledged by the Protestant world; they are facts which none can gainsay. The facts having been condensed into as little space as seemed consistent with a proper understanding of their application."[8]

Much of this history had passed before her in vision but not all the details and not always in precise sequence. In a statement read on October 30, 1911, carrying Ellen's written endorsement, W. C. White said:

"She (Ellen) made use of good and clear historical statements to help make plain to the reader the things which she is endeavoring to present. When I was a mere boy, I heard her read D'Aubigne's History of the Reformation to my father. She read to him a large part, if not the whole, of the five volumes. She has read other histories of the Reformation. This has helped her to locate and describe many of the events and the movements presented to her in vision."[9]

While verbs used are still generally present tense, the first person aspect is not present. The book was published in two bindings, one, olive in color, carrying the title The Great Controversy, the other in black cloth titled Spirit of Prophecy, volume 4. The book was sold to both Seventh-day Adventists and the general public. Fifty thousand copies were distributed within three years' time.[10]

The 1888 edition

The 1884 Great Controversy had enjoyed escalating sales. In 1887, C. H. Jones, manager of Pacific Press, informed Ellen that they needed to completely reset the type for the book because the old type was worn out. This was, therefore, a good time to improve and make corrections to the book.[11]

The 1884 book was reaching beyond the ranks of Seventh-day Adventists. Yet the terminology and, in some cases, the content was directed largely to Adventists. Expressions familiar to Adventists were sometimes incomprehensible to the ordinary reader. Also, some subjects were too briefly treated because the readers were expected to be familiar with them. Some adaptation of wording seemed desirable and also changing of the verb tense from present to past.[11]

At that time, Ellen was living in Europe, the land of Reformation history, a subject that is an important part of the book. Accordingly, she added a chapter on Huss and Jerome of Prague, who had previously been but briefly mentioned. More was added about Zwingli and John Calvin. Other chapters were enlarged and important additions were made about the sanctuary. Additional scriptures were introduced and footnote references were increased.[11]

The book was also translated into French and German. The translators and proofreaders, along with Ellen and her editors, would read, discuss, and translate chapters of the book as it was being reviewed for the new edition. By this means, the translators got the spirit of the work and so could improve the translation.[11]

The introduction describes the work of God's prophets and details God's commission to her to write the book:

"Through the illumination of the Holy Spirit, the scenes of the long-continued conflict between good and evil have been opened to the writer of these pages. From time to time I have been permitted to behold the working, in different ages, of the great controversy between Christ, the Prince of life, the Author of our salvation, and Satan, the prince of evil, the author of sin, the first transgressor of God's holy law.[12]

She wrote, "While writing the manuscript of Great Controversy I was often conscious of the presence of the angels of God.... And many times the scenes about which I was writing were presented to me anew in visions of the night, so that they were fresh and vivid in my mind."[13]

In the 1884 Great Controversy, Ellen quoted from D'Aubigne, Wylie, etc. In this enlargement, she brought in considerably more of such materials. At times she quoted, at times paraphrased, and at times depicted, in her own words, the events of history that formed the vehicle for presenting the larger picture, the behind-the-scenes controversy, that had been opened up to her in vision. In keeping with the thinking in those times, she and those associated with her did not consider this use of available materials as a matter that called for specific recognition.[11]

The 1911 edition

By 1907, so many copies had been printed that repairs had to be made on the most badly worn plates. At the same time, the illustrations were improved and a subject index was added. Then in 1910, C. H. Jones, the manager of Pacific Press, wrote saying that the plates were totally worn out and needed to be replaced before another printing could be done. Since White owned the printing plates, whatever would be done with The Great Controversy had to be done under her direction and at her expense.

At first, the procedures seemed routine and uncomplicated. No alterations in the text were contemplated, beyond technical corrections as might be suggested by Miss Mary Steward, a proofreader of long experience and member of Ellen's staff. However, Ellen White decided to examine the book closely and make changes as needed:

"When I learned that the Great Controversy must be reset, I determined that we would have everything closely examined, to see if the truths it contained were stated in the very best manner, to convince those not of our faith that the Lord had guided and sustained me in the writing of its pages."[14]

The book was reviewed according to the following items:

- The cultural attitude toward quoting sources had changed since the book was first printed, so full and verified references were noted for each quotation drawn from histories, commentaries, and other theological works.

- Time references, such as 'Forty years ago,' were reworded to read correct regardless of when read.

- More precise words were selected to set forth facts and truths more correctly and accurately.

- Truth was more kindly expressed to not repel the Catholic and the skeptical reader.

- Reference works were chosen that are readily available to most readers where facts might be challenged.

- Appendix notes were added.

In addition, Willie White, Ellen's son and agent, following Ellen's desires, sought helpful suggestions from others. He reported:

"We took counsel with the men of the Publishing Department, with State canvassing agents, and with members of the publishing committees, not only in Washington, D.C., but in California, and I asked them to kindly call our attention to any passages that needed to be considered in connection with the resetting of the book."[15]

Suggestions from around the world were received. These were blended into a group of points to study, first by Ellen's staff and finally by Ellen herself. While Ellen delegated the details of the work to members of her experienced office staff, she carried the responsibility for changes in the text. She was ultimate judge and final reviewer of the manuscript.

When the type was set and proof sheets were available from the publishers, a marked set, showing clearly both the old reading and the new, was submitted to Ellen for careful reading and approval. By early July 1911, the book was in the binderies of Pacific Press and the Review and Herald.[16]

In a letter to A. G. Daniells, White wrote in August 1910, shortly before the 1911 edition was published:

"Message after message has come to me from the Lord concerning—the dangers surrounding you and Elder Prescott. I have seen that Satan would have been greatly pleased to see Elders Prescott and Daniells undertake the work of a general overhauling of our books that have done a good work in the field for years."[17]

Other publishers

In addition to the major Adventist publishing houses, the book has also been printed and distributed by various independent initiatives. Remnant Publications sent more than 350,000 copies of the book to residents of Charlotte, North Carolina in 2014, after having already sent a million books to people in Manhattan and over 300,000 to people in Washington, D.C.[18]

Criticism

Plagiarism

Walter Rea (book published 1983), Donald McAdams (circulated unpublished manuscript ~1976), and other critics of The Great Controversy maintain that the book plagiarizes from a variety of sources.[19]

White stated in the introduction to both the 1888 and 1911 editions before any charges of plagiarism: "In some cases where a historian has so grouped together events as to afford, in brief, a comprehensive view of the subject, or has summarized details in a convenient manner, his words have been quoted; but except in a few instances no specific credit has been given, since they are not quoted for the purpose of citing that writer as authority, but because his statement affords a ready and forcible presentation of the subject. In narrating the experience and views of those carrying forward the work of reform in our own time, similar use has occasionally been made of their published works."[20][21]

Ramik cleared her of breaking the law of the land/time (copyright infringement/piracy), not of plagiarism in the academic sense.[22][23] In 1911, more than 70 years before charges of plagiarism, White wrote in the introduction to The Great Controversy her reason for quoting, in some cases without giving due credit, certain historians whose "statements affords a ready and forcible presentation on the subject."[24] That means that she acknowledged the charges of plagiarism and pleaded guilty (in the academic sense, not juridically).[25][26]

Catholicism

The book's tone toward the Papacy has been a target for criticism by some.[27]

Versions

Conflict of the Ages book series

- Vol. 1 Patriarchs and Prophets

- Vol. 2 Prophets and Kings

- Vol. 3 The Desire of Ages

- Vol. 4 The Acts of the Apostles

- Vol. 5 The Great Controversy

See also

Footnotes

- Ellen G. White, Spiritual Gifts, vol. 2, pp. 265–272. As quoted in "Telling the Story" by James R. Nix. Adventist Review March 20, 2008

- "Seventh-day Adventist 28 Fundamental Beliefs #26" (PDF). The Official Site of the Seventh-day Adventist world church. Retrieved August 9, 2017.

- Ellen G. White® Books and Pamphlets In Current Circulation(With Date of First Publication) Updated February 2012

- http://www.whiteestate.org/guides/gc.pdf.

- Ellen.G. White Writings CD Data Disk: Comprehensive Research Edition, 2008

- White 1985, pp. 366-380.

- White 1984, p. 211.

- White, Ellen G. (1888). The Great Controversy. Review and Herald. pp. xi.

- White, Ellen G. (1980). Selected Messages. Review and Herald. p. 437.

- White 1984, pp. 211-214.

- White 1984, pp. 435-443.

- White, Ellen G. (1888). The Great Controversy. Review and Herald. pp. x.

- White, unpublished manuscript; as quoted by Arthur White; as quoted in Peterson, 60

- White, E.G., (1911), Letter 56

- White, W.C. (1911), letter to "Our General Missionary Agents," July 24, (see also 3SM, pp. 439, 440)

- White, Arthur L. (1984). Ellen G. White: The Later Elmshaven Years. 6. pp. 302–321.

- White, E.G. (1910) Other Manuscripts vol.10 "Counsels involving W. W. Prescott and His Work"

- Bradford, Ben. "That Book You Got In The Mail". WFAE 90.7 Charlotte's NPR News Source. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- Donald McAdams, unpublished document on the John Hus chapter, 250 pages. Dated within a decade of 1976; as cited in Jonathan M. Butler, "The Historian as Heretic"; as reprinted in Prophetess of Health by Ronald Numbers, p34

- White, Ellen G. (1888). "Author's Preface". The Great Controversy (PDF). Ellen G. White Estate, Inc. pp. 15–16.

- White, Ellen G. (1911). "Author's Preface". The Great Controversy (PDF). Ellen G. White Estate, Inc. pp. 14–15.

- The Ramik Report Memorandum of Law Literary Property Rights 1790 – 1915 Archived December 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Was Ellen G. White A Plagiarist?". Ellen G. White Writings. Retrieved 2018-10-28.

Ellen G. White was not a plagiarist and her works did not constitute copyright infringement/piracy.

- Ellen G. White. The Conflict of the Ages Story, Vol. 5. The Great Controversy—Illustrated. Digital Inspiration. p. 16.

The great events which have marked the progress of reform in past ages are matters of history, well known and universally acknowledged by the Protestant world; they are facts which none can gainsay. This history I have presented briefly, in accordance with the scope of the book, and the brevity which must necessarily be observed, the facts having been condensed into as little space as seemed consistent with a proper understanding of their application. In some cases where a historian has so grouped together events as to afford, in brief, a comprehensive view of the subject, or has summarized details in a convenient manner, his words have been quoted; but in some instances no specific credit has been given, since the quotations are not given for the purpose of citing that writer as authority, but because his statement affords a ready and forcible presentation of the subject. In narrating the experience and views of those carrying forward the work of reform in our own time, similar use has been made of their published works.

Cf. The Great Controversy, p. xi.4 1911 edition. - McArthur, Benjamin (Spring 2008). "Point of the Spear: Adventist Liberalism and the Study of Ellen White in the 1970s" (PDF). Spectrum. 36 (2): 48. ISSN 0890-0264. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

Rather, he was always at pains to emphasize that Mrs. White herself acknowledged indebtedness in the book's Introduction:

- "But liberal scholarship prevailed in one arena: it permanently revised our understanding of Ellen White's historical writings. For decades, a type of verbal inspiration dominated popular Adventism, shaping the church culture to a degree that today's generation of Adventist youth could hardly imagine. Within at least the educated mainstream church, that is no longer the case." McArthur (2008: 53).

- "Will 'The Great Controversy' Project Harm Adventism?". spectrummagazine.org. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

References

- White, Arthur L. (1985). Ellen G. White: The Early Years. 1. Ellen G. White Estate, Inc.

- White, Arthur L. (1984). Ellen G. White: The Lonely Years. 3. Ellen G. White Estate, Inc.

External links

- Online version at the Ellen G. White Estate

- Documents regarding the book from the White Estate

- W. W. Prescott and the 1911 Edition of The Great Controversy by Arthur L. White

- The 1911 Edition of "The Great Controversy": An Explanation of the Involvements of the 1911 Revision

- How Ellen White's Books Were Written: Addresses to Faculty and Students at the 1935 Advanced Bible School, Angwin, California by William C. White

- The Great Controversy, a statement made by Willie White before the General Conference Council on October 30, 1911

- Original 1858 edition in many languages at EarlySDA

- Comparison of contemporary writers' works and their possible influence on the 1911 Great Controversy by Walter Rea

- Discussion on how pivotal the Great Controversy vision has been to the SDA Church, by James R. Nix "Adventist Review" March 20, 2008