The Long and Winding Road

"The Long and Winding Road" is a song by the English rock band the Beatles from their 1970 album Let It Be. It was written by Paul McCartney and credited to Lennon–McCartney. When issued as a single in May 1970, a month after the Beatles' break-up, it became the group's 20th and last number-one hit on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in the United States.[2]

| "The Long and Winding Road" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

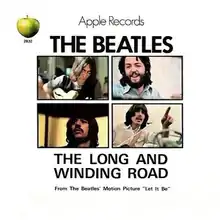

US picture sleeve | ||||

| Single by the Beatles | ||||

| from the album Let It Be | ||||

| B-side | "For You Blue" | |||

| Released | 11 May 1970 | |||

| Recorded | 26 January 1969; 1 April 1970 | |||

| Studio | Apple and EMI, London | |||

| Genre | Rock[1] | |||

| Length | 3:40 | |||

| Label | Apple | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Lennon–McCartney | |||

| Producer(s) | Phil Spector | |||

| The Beatles US singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

The main recording of the song took place in January 1969 and featured a sparse musical arrangement. When preparing the tapes from these sessions for release in April 1970, producer Phil Spector added orchestral and choral overdubs. Spector's modifications angered McCartney to the point that when the latter made his case in the English High Court for the Beatles' disbandment, he cited the treatment of "The Long and Winding Road" as one of six reasons for doing so. New versions of the song with simpler instrumentation were subsequently released by McCartney and by the Beatles.

In 2011, Rolling Stone ranked "The Long and Winding Road" at number 90 on their list of 100 greatest Beatles songs.

Inspiration

Paul McCartney said he came up with the title "The Long and Winding Road" during one of his first visits to his property High Park Farm, near Campbeltown in Scotland,[4] which he purchased in June 1966.[5] The phrase was inspired by the sight of a road "stretching up into the hills" in the remote Highlands surroundings of lochs and distant mountains.[4] He wrote the song at his farm in 1968, inspired by the growing tension among the Beatles.[3][6] Based on other comments McCartney has made, author Howard Sounes writes, the lyrics can be seen as McCartney expressing his anguish at the direction of his personal life, as well as a nostalgic look back at the Beatles' history.[7] McCartney recalled: "I just sat down at my piano in Scotland, started playing and came up with that song, imagining it was going to be done by someone like Ray Charles. I have always found inspiration in the calm beauty of Scotland and again it proved the place where I found inspiration."[3]

Once back in London, McCartney recorded a demo version of "The Long and Winding Road" during one of the recording sessions for The Beatles.[8] Later, he offered the song to Tom Jones on the condition that the singer release it as his next single. In Jones' recollection, he was forced to turn it down since his record company were about to issue "Without Love" as a single.[9]

The song takes the form of a piano-based ballad, with conventional chord changes.[10] McCartney described the chords as "slightly jazzy" and in keeping with Charles' style.[6] The song's home key is E-flat major but it also uses the relative C minor.[10] Lyrically, it is a sad and melancholic song, with an evocation of an as-yet unrequited, though apparently inevitable, love.

In an interview in 1994, McCartney described the lyric more obliquely: "It's rather a sad song. I like writing sad songs, it's a good bag to get into because you can actually acknowledge some deeper feelings of your own and put them in it. It's a good vehicle, it saves having to go to a psychiatrist."[11]

The opening theme is repeated throughout. The song lacks a traditional chorus, and the melody and lyrics are ambiguous about the opening stanza's position in the song; it is unclear whether the song has just begun, is in the verse, or is in the bridge.[10]

Recording

January 1969

The Beatles recorded several takes of "The Long and Winding Road" at their Apple Studio in central London on 26 January 1969 and again on 31 January. The line-up on the track was McCartney on lead vocals and piano, John Lennon on bass guitar, George Harrison on electric guitar, Ringo Starr on drums, and guest keyboardist Billy Preston on Rhodes piano. This was during a series of sessions for an album and film project then known as Get Back. Lennon, usually the band's rhythm guitarist, played bass only occasionally and made several mistakes on the recording.[3]

In May 1969, Glyn Johns, who had been asked by the Beatles to compile and mix the Get Back album, selected the 26 January recording. Since the song had been deemed unsuitable for inclusion in the band's filmed rooftop concert on 30 January, the Beatles also taped a master version of "The Long and Winding Road" at Apple the following day.[12] This 31 January version, which had slightly different lyrics from the released take, and was recorded with Johns in an unofficial producer's role, was used in the film, subsequently titled Let It Be.[13] For the 1969 and 1970 versions of the Get Back album – both of which were rejected by the Beatles – Johns used the 26 January mix as released on the Anthology 3 album in 1996.[14]

April 1970

In early 1970, Lennon and the Beatles' manager, Allen Klein, turned over the recordings to American producer Phil Spector with the hope of salvaging an album, which was then titled Let It Be.[3] McCartney had become estranged from his bandmates at this time, due to his opposition to Klein's appointment as manager. Several weeks were lost before McCartney replied to messages requesting his approval for Spector to begin working on the recordings.[15] Spector chose to return to the same 26 January recording of "The Long and Winding Road".[14]

Spector made various changes to the songs. His most dramatic embellishments occurred on 1 April 1970, the last ever Beatles recording session, when he added orchestral overdubs to "The Long and Winding Road", "Across the Universe" and "I Me Mine" at Abbey Road Studios. The only member of the Beatles present was Starr, who played drums with the session musicians to create Spector's characteristic "Wall of Sound". Already known for his eccentric behaviour in the studio, Spector was in a peculiar mood that day, according to balance engineer Peter Bown: "He wanted tape echo on everything, he had to take a different pill every half-hour and had his bodyguard with him constantly. He was on the point of throwing a wobbly, saying 'I want to hear this, I want to hear that. I must have this, I must have that.'" The orchestra became so annoyed by Spector's behaviour that the musicians refused to play any further; at one point, Bown left for home, forcing Spector to telephone him and persuade him to come back after Starr had told Spector to calm down.[16]

Spector succeeded in overdubbing "The Long and Winding Road", using eight violins, four violas, four cellos, three trumpets, three trombones, two guitars, and a choir of 14 women, which makes 38 musicians altogether.[17] The orchestra was scored and conducted by Richard Hewson, a young London arranger who had worked with Apple artists Mary Hopkin[18] and James Taylor.[19] This lush orchestral treatment was in direct contrast to the Beatles' stated intentions for a "real" recording when they began work on Get Back.[18]

On 2 April, Spector sent each of the Beatles an acetate of the completed album with a note saying: "If there is anything you'd like done to the album, let me know and I'll be glad to help ... If you wish, please call me about anything regarding the album tonight."[20] All four of the band members sent him their approval by telegram.[21][22]

Dispute over Spector's overdubs

According to author Peter Doggett, McCartney had felt the need to accommodate his bandmates when accepting Spector's version of Let It Be; but, following his announcement of the Beatles' break-up in a press release accompanying the release of his solo album, McCartney, on 9 April, he repeatedly listened again to "The Long and Winding Road" and came to resent Spector's additions.[23] On 14 April, with manufacturing underway for Let It Be, he sent a terse letter to Klein, demanding that the harp be removed from the song and that the other added instrumentation and voices be reduced.[24] McCartney concluded the letter with the words: "Don't ever do it again."[25] Klein attempted to phone McCartney but he had changed his number without informing Apple; Klein then sent a telegram asking McCartney to contact him or Spector about his concerns. According to Klein, "The following day, a message was relayed to me [from McCartney] that the letter spoke for itself."[26] With Let It Be scheduled for release in advance of the similarly titled documentary film, Klein allowed the production process to continue with Spector's version of "The Long and Winding Road" intact.[27]

In an interview published by the Evening Standard in two parts on 22 and 23 April 1970, McCartney said: "The album was finished a year ago, but a few months ago American record producer Phil Spector was called in by Lennon to tidy up some of the tracks. But a few weeks ago, I was sent a re-mixed version of my song 'The Long and Winding Road' with harps, horns, an orchestra, and a women's choir added. No one had asked me what I thought. I couldn't believe it."[28] The Beatles' usual producer, George Martin, called the remixes "so uncharacteristic" of the Beatles, while Johns, who was denied a production credit by Lennon,[29] described Spector's embellishments as "revolting ... just puke".[30]

McCartney asked Klein to dissolve the Beatles' partnership, but was refused. Exasperated, he took the case to the High Court in London in early 1971, naming Klein and the other Beatles as defendants. Among the six reasons McCartney gave for dissolving the Beatles was that Klein's company, ABKCO, had imposed changes to "The Long and Winding Road" without consulting McCartney.[31] In his written affidavit, Starr countered this statement by saying that when Spector had sent acetates of Let It Be to each of the Beatles for their approval, with a request also for feedback: "We all said yes. Even at the beginning Paul said yes. I spoke to him on the phone, and said, 'Did you like it?' and he said, 'Yeah, it's OK.' He didn't put it down."[20] Starr added: "And then suddenly he didn't want it to go out. Two weeks after that, he wanted to cancel it."[22] Author Nicholas Schaffner commented that, in light of McCartney's contention in the High Court, it was surprising that he personally accepted the band's Grammy Award for Let It Be in March 1971 – when the album won in the category Best Original Score Written for a Motion Picture or Television Special[32] – and that he chose to feature his wife Linda's voice so prominently on his post-Beatles recordings.[33]

Speaking shortly after the overdubbing sessions, Spector said that he had asked whether any of the Beatles would like to help him produce the album, but none of them had wanted to.[21] He also said that his hand was forced into orchestrating "The Long and Winding Road" to cover the poor quality of Lennon's bass playing.[34] In his book Revolution in the Head, Beatles scholar Ian MacDonald wrote: "The song was designed as a standard to be taken up by mainstream balladeers. … It features some atrocious bass-playing by Lennon, prodding clumsily around as if uncertain of the harmonies and making many comical mistakes. Lennon's crude bass playing on 'The Long and Winding Road', though largely accidental, amounts to sabotage when presented as finished work."[3] In 2003, Spector called McCartney's criticism "hypocritical", alleging that "Paul had no problem picking up the Academy Award [sic] for the Let It Be movie soundtrack,[nb 1] nor did he have any problem in using my arrangement of the string and horn and choir parts when he performed it during 25 years of touring on his own. If Paul wants to get into a pissing contest about it, he's got me mixed up with someone who gives a shit."[37]

Release

The song was released on the Let It Be album on 8 May 1970.[38] On 11 May, seven days before the album's North American release,[39] Apple issued "The Long and Winding Road" as a single in the United States with "For You Blue" on the B-side.[40] In the context of the recent news regarding the Beatles' split, the song captured the sadness that many listeners felt.[41]

On 13 June 1970, it became the Beatles' twentieth and final number-one single on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in America and held the top position for a second week. The band thereby set the all-time record for number of chart-topping singles on the Billboard Hot 100. The Beatles achieved this feat in a period of less than six-and-a-half years, starting with "I Want to Hold Your Hand" on 1 February 1964, during which they topped the Hot 100 in one out of every six weeks.[42]

The single's contemporary US sales were insufficient for gold accreditation by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).[43] In February 1999, the song was certified platinum by the RIAA for sales of 1,000,000.[44]

Critical reception

Let It Be received largely unfavourable reviews from music critics,[45][46] many of whom ridiculed Spector's use of orchestration, particularly on "The Long and Winding Road".[47] Richard Williams of Melody Maker wrote that "Paul's songs seem to be getting looser and less concise, and Spector's orchestrations add to the Bacharach atmosphere. The strings add a pleasant fullness in places, but intrude badly near the end and the harps are too much."[48][49] Rolling Stone's reviewer, John Mendelsohn, was especially critical of Spector's work on the song,[33] saying: "He's rendered 'The Long and Winding Road' ... virtually unlistenable with hideously cloying strings and a ridiculous choir that serve only to accentuate the listlessness of Paul's vocal and the song's potential for further mutilation at the hands of the countless schlock-mongers who will undoubtedly trip all over one another in their haste to cover it." Mendelsohn said that while the song was a "slightly lesser chapter in the ongoing story of McCartney as facile romanticist", "it might have eventually begun to grow on one as unassumingly charming" without Spector's "oppressive mush".[50]

In 1973, musicologist and critic Wilfrid Mellers wrote: "The music has a tremendous expectancy … Whether or no Paul approved of the plush scoring of 'The Long and Winding Road', it works not because it guys the feeling but because the feeling has integrity."[51] MacDonald said: "With its heart-breaking suspensions and yearning backward glances from the sad wisdom of the major key to the lost loves and illusions of the minor, 'The Long and Winding Road' is one of the most beautiful things McCartney ever wrote. Its words, too, are among his most poignant, particularly the reproachful lines of the brief four-bar middle section. A shame Lennon didn't listen more generously."[52]

According to Williams, writing in his book Phil Spector: Out of His Head, Spector's mistake was in "taking McCartney at his face value" and emphasising the sentimental qualities that George Martin's orchestral arrangements for the Beatles had successfully tempered. Williams added: "Some might say that this track, above all others, epitomises Paul McCartney, and that when Spector sent the saccharine strings sweeping in after the first line of vocal, he was merely highlighting the reality."[53] In a 2003 review for Mojo, shortly after the announcement that McCartney planned to issue "a string-less Let It Be", John Harris opined: "As someone who experiences a Proustian rush every time the orchestra crash-lands in The Long And Winding Road, I can only implore him to think again. Besides, underneath all the Wagnerian gloop, John's bass playing is horribly out of tune ..."[54] Referring to the version subsequently released without the controversial overdubs, Adam Sweeting of The Guardian said the song was "indubitably improved by the removal of Spector's wall of schmaltz, but it's still teeth-clenchingly mawkish".[55]

In 2011, Rolling Stone placed "The Long and Winding Road" at number 90 on its list of "The 100 Greatest Beatles Songs".[56] On a similar list compiled by Mojo in 2006, the song appeared at number 27. In his commentary for the magazine, Brian Wilson described it as his "all time favourite Beatles track", saying that while the Beatles were "genius songwriters", this song was distinguished by a "heart-and-soul melody". Wilson concluded: "When they broke up I was heartbroken. I think they should have kept going."[57]

Other recordings

Since the original release in 1970, there have been six additional recordings released by McCartney.[58] The 26 January 1969 take, without the orchestration and overdubs, was issued on Anthology 3 in 1996.[59] This was the same take issued in 1970, and includes a bridge section spoken, rather than sung, by McCartney that was omitted in Spector's remix. "The Long and Winding Road" provided the working title for Apple executive Neil Aspinall's early version of the documentary film that became The Beatles Anthology.[60] The title was changed in the 1990s after Harrison objected to the project being named after McCartney's song.[61]

In 2003, McCartney persuaded Starr and Ono (as Lennon's widow) to release Let It Be... Naked.[3] McCartney claimed that his long-standing dissatisfaction with the released version of "The Long and Winding Road" (and the entire Let It Be album) was in part the impetus for the new version. The new album included a later take of "The Long and Winding Road", recorded on 31 January. With no strings or other added instrumentation beyond that which was played in the studio at the time, it was closer to the Beatles' original intention than the 1970 version.[3] This take is also the one seen in the film Let It Be and on the Beatles' 2015 video compilation 1.[62] Starr said of the Let It Be... Naked version: "There's nothing wrong with Phil's strings [on the 1970 release], this is just a different attitude to listening. But it's been 30-odd years since I've heard it without all that and it just blew me away."[3]

McCartney re-recorded "The Long and Winding Road" for the soundtrack to his 1984 film Give My Regards to Broad Street. George Martin produced the track, which authors Chip Madinger and Mark Easter describe as having a Las Vegas-type arrangement.[63][nb 2] A second new studio recording of the song was made by McCartney in 1989 and used as a B-side of single releases from his Flowers in the Dirt album, starting with the "Postcard Pack" vinyl format of "This One".[65]

"The Long and Winding Road" became a staple of McCartney's post-Beatles concert repertoire. On the 1976 Wings Over the World Tour, where it was one of the few Beatles songs played, it was performed on piano in a sparse arrangement using a horn section. On McCartney's 1989 solo tour and since, it has generally been performed on piano with an arrangement using a synthesiser mimicking strings, but this string sound is more restrained than on the Spector recorded version.[66] The live performance recording of the Rio de Janeiro concert in April 1990 is on the album Tripping the Live Fantastic. McCartney also played the song to close the Live 8 concert in London.[67]

Several other artists have performed or recorded "The Long and Winding Road". As McCartney had originally envisaged,[6] Ray Charles recorded a cover version in 1973, which was released on his 2006 album Ray Sings, Basie Swings.[68] In the US, a recording by Billy Ocean peaked at number 24 on Billboard's Adult Contemporary chart.[69] Cilla Black released a version on her 1973 Martin-produced album Day by Day with Cilla,[70] a recording that McCartney described as the definitive version of the song.[71][nb 3]

Other versions include a cover by Leo Sayer on the 1976 "All This And World War II" soundtrack, a 1999 Royal Albert Hall performance by George Michael, a 1978 recording by Peter Frampton, and a 2010 performance at the White House by Faith Hill when Barack Obama gave McCartney the Gershwin Prize.[73] In 2002, British Pop Idol series one contestants Will Young and Gareth Gates recorded a version released as a double A-side with Gates' version of "Suspicious Minds"; the single topped the UK Singles Chart and the Scottish Singles Chart.[74][75] The duet by itself also reached number four in Ireland.[76] In 2007, "The Long and Winding Road" was included on Barry Manilow's The Greatest Songs of the Seventies album, which debuted at number four on the Billboard 200 chart.[77]

Personnel

According to Walter Everett:[78]

The Beatles

- Paul McCartney – vocal, piano

- John Lennon – six-string bass

- George Harrison – electric guitar

- Ringo Starr – drums

Additional musicians

- Billy Preston – Fender Rhodes

- Uncredited orchestral musicians – 18 violins, 4 violas, 4 cellos, harp, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, 2 guitars, 14 female voices[17]

- Richard Hewson – orchestral arrangement[18]

- John Barham – choral arrangement[79]

Charts and certifications

Weekly charts

|

Year-end charts

Certifications

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Although McCartney accepted the Grammy Award in Los Angeles, a month before the Oscars ceremony,[35] the Academy Award for Best Original Song Score was picked up by Quincy Jones, who says McCartney refused to attend.[36]

- Madinger and Easter rue that McCartney chose to revisit some of his Beatles songs in Give My Regards to Broad Street. They comment that the 1984 version fails to support how "near and dear to his heart" the song was and McCartney's complaint that Spector had "overproduced" the Beatles' recording.[64]

- In August 2015, the Beatles' recording of "The Long and Winding Road" was played at Black's funeral as the coffin left the church.[72]

References

- Wyman, Bill. "All 213 Beatles Songs, Ranked From Worst to Best". Vulture. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Whitburn 2000.

- Merritt, Mike (16 November 2003). "Truth behind ballad that split Beatles". Sunday Herald. Archived from the original on 27 April 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- Sounes 2010, p. 181.

- Miles 2001, p. 234.

- Duca, Lauren (13 June 2014). "'The Long And Winding Road' Led to the Beatles' Final No. 1 Single". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- Sounes 2010, pp. 239–40.

- Lewisohn 2005, p. 156.

- Owens, David (3 June 2012). "Sir Tom Jones reveals the Beatles hit that was written for him". WalesOnline. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- Pollack, Alan W. (1999). "Notes on 'The Long and Winding Road'". Soundscapes. Archived from the original on 29 July 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- "Let It Be". The Beatles Interview Database. 2004. Archived from the original on 12 December 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2004.

- Miles 2001, p. 333.

- Sulpy & Schweighardt 1999, pp. 301, 307–08.

- Spizer 2003, pp. 74–75.

- Doggett 2011, pp. 115–16.

- Lewisohn 2005, pp. 198–199.

- MacDonald 2005, p. 339.

- Lewisohn 2005, p. 199.

- Castleman & Podrazik 1976, pp. 71, 189.

- Doggett 2011, p. 123.

- Irvin, Jim (November 2003). "Get It Better: The Story of Let It Be… Naked". Mojo. Available at Rock's Backpages Archived 17 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine (subscription required).

- Miles 2001, p. 373.

- Doggett 2011, pp. 130–31.

- Doggett 2011, p. 131.

- The Beatles 2000, p. 350.

- Doggett 2011, p. 132.

- Doggett 2011, pp. 120–21, 130, 132.

- Spitz 2005, p. 851.

- Miles 2001, p. 374.

- Sounes 2010, p. 271.

- Badman 2001, pp. 23, 26.

- Badman 2001, p. 32.

- Schaffner 1978, p. 138.

- "Phil Spector rants about his relationship with The Beatles ahead of his murder retrial". Daily Mirror. London. 25 October 2008. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- Badman 2001, pp. 32, 33.

- "Search: Quincy Jones' Memory of the Beatles Oscar Win". Witnify. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Noden, Merrell (2003). "Extra-celestial". Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days of Revolution (The Beatles' Final Years – Jan 1, 1968 to Sept 27, 1970). London: Emap. p. 127.

- Castleman & Podrazik 1976, pp. 89–90.

- Miles 2001, p. 377.

- Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 90.

- Rodriguez 2010, p. 3.

- Schaffner 1978, p. 216.

- Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 332.

- "Search: The Beatles, Long and Winding Road". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- Badman 2001, p. 9.

- Unterberger, Richie. "The Beatles Let It Be". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- Williams 2003, p. 146.

- Williams, Richard (9 May 1970). "Beatles R.I.P.". Melody Maker. p. 5.

- Sutherland, Steve, ed. (2003). NME Originals: Lennon. London: IPC Ignite!. p. 75.

- Mendelsohn, John (11 June 1970). "The Beatles: Let It Be". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- Mellers 1973, p. 137.

- MacDonald 2005, p. 341.

- Williams 2003, p. 147.

- Harris, John (2003). "Let It Be: Can You Dig It?". Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days of Revolution (The Beatles' Final Years – Jan 1, 1968 to Sept 27, 1970). London: Emap. p. 133.

- Sweeting, Adam (14 November 2003). "The Beatles: Let It Be... Naked". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- "100 Greatest Beatles Songs: 90. 'The Long and Winding Road'". rollingstone.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- Alexander, Phil; et al. (July 2006). "The 101 Greatest Beatles Songs". Mojo. p. 84.

- Womack 2014, p. 569.

- Lewisohn, Mark (1996). Anthology 3 (booklet). The Beatles. Apple Records. pp. 30, 31. 34451.

- Doggett 2011, pp. 138, 309.

- Doggett 2011, p. 309.

- Rowe, Matt (18 September 2015). "The Beatles 1 to Be Reissued with New Audio Remixes ... and Videos". The Morton Report. Archived from the original on 29 December 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- Madinger & Easter 2000, pp. 275, 278.

- Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 278.

- Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 309.

- Badman 2001.

- "Live 8 Rocks the Globe". The New York Times. 3 July 2005. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- Tamarkin, Jeff. "Ray Charles Ray Sings, Basie Swings". AllMusic. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- Whitburn 1993, p. 178.

- "Day by Day with Cilla (Official Discography)". Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- Farquhar, Simon (2 August 2015). "Cilla Black: Singer who was signed by Brian Epstein and went on to forge a successful career as a much-loved presenter". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 February 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Boyle, Danny (20 August 2015). "Cilla Black funeral: Sir Cliff Richard leads tributes to queen of showbiz". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Womack 2014, p. 570.

- "Official Singles Chart Top 100 29 September 2002 – 05 October 2002". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- "Official Scottish Singles Sales Chart Top 100 29 September 2002 – 05 October 2002". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- "The Irish Charts – Search the Charts". Irish Singles Chart. Archived from the original on 3 June 2009. Retrieved 16 August 2019. Enter Will Young and Gareth Gates into the Search by Artist field and press Enter.

- "Barry Manilow Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- Everett 1999, p. 229.

- Lewisohn 2010, p. 349.

- "Go-Set Australian charts – 19 September 1970". poparchives.com.au. Archived from the original on 29 March 2007. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- Kent, David (2005). Australian Chart Book (1940–1969). Turramurra: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-44439-5.

- "Ultratop.be – The Beatles – The Long and Winding Road" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- "Top Singles – Volume 13, No. 18: Jun 20, 1970". Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- "Dutchcharts.nl – The Beatles – The Long and Winding Road" (in Dutch). Single Top 100. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- "flavour of new zealand – search listener". www.flavourofnz.co.nz. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- "Swisscharts.com – The Beatles – The Long and Winding Road". Swiss Singles Chart. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- "The Beatles Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- Whitburn 1993, p. 25.

- Hoffmann, Frank (1983). The Cash Box Singles Charts, 1950–1981. Metuchen, NJ & London: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. pp. 32–34.

- "Offizielle Deutsche Charts" (Enter "Beatles" in the search box) (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- "RPM's Top 100 of 1970". Library and Archives Canada. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- "Year-End Charts, Hot 100 Songs, 1970". billboard.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "The Cash Box Year-End Charts: 1970". cashboxmagazine.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "American single certifications – The Beatles – Long and Winding Road". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 14 May 2016. If necessary, click Advanced, then click Format, then select Single, then click SEARCH.

Sources

- Badman, Keith (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-8307-6.

- The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-2684-8.

- Castleman, Harry; Podrazik, Walter J. (1976). All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-25680-8.

- Doggett, Peter (2011). You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the Breakup. New York, NY: It Books. ISBN 978-0-06-177418-8.

- Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver Through the Anthology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512941-5.

- Lewisohn, Mark (1996). The Complete Beatles Chronicle. Chancellor Press. ISBN 0-7607-0327-2.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2005) [1988]. The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions: The Official Story of the Abbey Road Years 1962–1970. London: Bounty Books. ISBN 978-0-7537-2545-0.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2010). The Complete Beatles Chronicle: The Definitive Day-By-Day Guide to the Beatles' Entire Career. Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-56976-534-0.

- MacDonald, Ian (2005). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties (Second Revised ed.). London: Pimlico (Rand). ISBN 1-84413-828-3.

- Madinger, Chip; Easter, Mark (2000). Eight Arms to Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium. Chesterfield, MO: 44.1 Productions. ISBN 0-615-11724-4.

- Mellers, Wilfrid (1973). Twilight of the Gods: The Beatles in Retrospect. London: Faber.

- Miles, Barry (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-8308-9.

- Rodriguez, Robert (2010). Fab Four FAQ 2.0: The Beatles' Solo Years, 1970–1980. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.

- Sounes, Howard (2010). Fab: An Intimate Life of Paul McCartney. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-723705-0.

- Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles: The Biography. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-80352-9.

- Spizer, Bruce (2003). The Beatles on Apple Records. New Orleans: 498 Productions. ISBN 0-9662649-4-0.

- Sulpy, Doug; Schweighardt, Ray (1999). Get Back: The Unauthorized Chronicle of The Beatles' Let It Be Disaster. New York, NY: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-19981-3.

- Whitburn, Joel (1993). Joel Whitburn's Top Adult Contemporary, 1961–1993. Menomonee Falls, WI: Record Research. ISBN 978-0-898200997.

- Whitburn, Joel (2000). 40 Top Hits. Billboard Books.

- Williams, Richard (2003). Phil Spector: Out of His Head. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-9864-3.

- Womack, Kenneth (2014). The Beatles Encyclopedia: Everything Fab Four. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-39171-2.