The Lost City of Z (book)

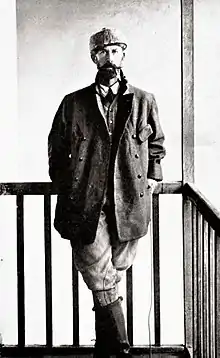

The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon is the debut non-fiction book by American author David Grann. The book was published in 2009 and recounts the activities of the British explorer Percy Fawcett who, in 1925, disappeared with his son in the Amazon while looking for an ancient lost city. For decades explorers and scientists have tried to find evidence of his party and of the "Lost City of Z".

Cover of the first US edition | |

| Author | David Grann |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Percy Fawcett |

| Genre | Non-fiction |

| Publisher | Doubleday |

Publication date | February 2009 |

| Media type |

|

| Pages | 352 |

| ISBN | 978-0-385-51353-1 |

| OCLC | 226038067 |

| 918.1/1046 22 | |

| LC Class | F2546 .G747 2009 |

Grann also recounts his own journey into the Amazon, by which he discovered new evidence about how Fawcett may have died. He learned that Fawcett may have come upon "Z" without knowing it.[1] The book claims as many as 100 people may have died or disappeared (and are presumed dead) searching for Fawcett over the years; however, the more historically accurate toll, according to John Hemming, is one.[2] The Lost City of Z was the basis of a 2016 feature film of the same name, written and directed by James Gray.

Kuhikugu

First in his 2005 article "The Lost City of Z" and later in the book he developed and published with the same title, David Grann reported on excavations by the archeologist Michael Heckenberger at a site in the Amazon Xingu region that might be the long-rumored lost city. The ruins were surrounded by several concentric circular moats, with evidence of palisades that had been described in the folklore and oral history of nearby tribes. Heckenberger also found evidence of wooden structures and roads that cut through the jungle. Black Indian earth showed evidence that humans had added supplements to the soil to increase its fertility to support agriculture.

Perhaps most intriguing were the direct parallels between the site, referred to as Kuhikugu, and tribes of the area. Pottery methods had remained nearly identical and the tribes followed a diet that prohibited several sources of food—striking considering the long-held belief that such prohibitions would mean death in the harsh rainforest. Contemporary villages are laid out in patterns similar to those seen at three sites of the ancient cities.

Kuhikugu encompasses more than 20 settlements, each supporting as many as 5,000 people. Construction methods showed sophisticated engineering. The structures were made of wood, supporting a society that flourished from approximately 200 A.D. until around 1600, according to carbon-dating data obtained from the moats and pottery. Their constructions included bridges across some of the great rivers of the Amazon. Their monuments extended horizontally, rather than being built as the pyramidal structures developed by the Mayan or Aztec peoples.

The settlements and civilization of these people appeared to have lasted long enough for them to have had contact with Europeans. Many died due to new infectious diseases, which may have been carried by some of their usual indigenous trading partners, rather than directly by Europeans. The high rate of fatality of these epidemics disrupted the people and their society: in only a few years, they were so devastated by disease that they had virtually died out. The earliest conquistadors left records of their glimpses of this civilization, but by the time they tried to explore the rainforest again, the indigenous people were all but gone. The jungle was quickly reclaiming the land.[3]

Reception

The Lost City of Z was reviewed by Rich Cohen in the Sunday New York Times Book Review, who said it was "a powerful narrative, stiff lipped and Victorian at the center, trippy at the edges, as if one of those stern men of Conrad had found himself trapped in a novel by García Márquez."[4]

Critic Michiko Kakutani ranked it as one of the ten best books of 2009.[5] In her review, Kakutani wrote that it "is at once a biography, a detective story and a wonderfully vivid piece of travel writing that combines Bruce Chatwinesque powers of observation with a Waugh-like sense of the absurd. Mr. Grann treats us to a harrowing reconstruction of Fawcett’s forays into the Amazonian jungle, as well as an evocative rendering of the vanished age of exploration. . . . Suspenseful. . . Rollicking . . . Fascinating . . . It reads with all the pace and excitement of a movie thriller and all the verisimilitude and detail of firsthand reportage.”[6]

The Washington Post described it as "a thrill ride from start to finish."[7] The book appeared on several "best" and "notable books of the year" lists, including that of Entertainment Weekly, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Publisher's Weekly, Sunday New York Times, Christian Science Monitor, Bloomberg, the Providence Journal, The Globe and Mail, Evening Standard, Amazon, and McClatchy Newspapers. Barnes & Noble ranked The Lost City of Z as the single best nonfiction book of 2009.

At the same time, critics have pointed out inaccuracies and distortions by Grann. Writing for The Wall Street Journal, Simon Winchester said the book was "captivating" but faulted Grann's credulity, especially when he imagined that he was seeing the ruins of "Z". Winchester writes, "Oh, please. It is all just too pat, too wanting in healthy skepticism."[8] Hugh Thomson writes in The Washington Post that Grann's book is "a source of distortion, as it ignores or inflates much available material on Fawcett."[9]

John Hemming dismissed much of the book as hyperbolic in his review for The Times Literary Supplement, concluding, "It is a pity that a writer as good as Grann chose to study this unimportant, disagreeable and ultimately pathetic man. It is an even greater pity that he decided to inflate and distort so much of this sad story." Hemming assails Grann for dabbling in the "green-hell" genre, where the jungle is depicted as offering some new lethal threat with each footstep. The review notes Grann's exaggerations of Fawcett's exploits. Hemming said that Grann's claim that Fawcett "helped redraw the map of South America" was a "staggering exaggeration", given the insignificance of his actual expeditions. He describes Grann as "totally wrong" about both Fawcett's beliefs about El Dorado and the current state of scholarship on the subject. Hemming said that "there is no excuse for [Grann's] fantasies" about the dangers of indigenous tribes and the depth of Fawcett's contact with them.[10]

Awards and honors

- New York Times bestseller (Nonfiction, 2009)

- Samuel Johnson Prize, shortlist (2009)

- Amazon's Best Books of the Year (#58, 2009)

- Publishers Weekly’s Top 10 Best Books: 2009

- Publishers Weekly's Best Books: 2009

- New York Times Notable Book of the Year (Nonfiction, 2009)

- ALA Notable Books for Adults (2010)

- Indies Choice Book Award (Adult Non-fiction, 2010)

- Globe and Mail Best Book (Travel 2009)

- The Essential Man's Library: 50 Non-Fiction Adventure Books

- Christian Science Monitor Best Book (Nonfiction, 2009)

Film adaptation

The Lost City of Z was optioned by Brad Pitt’s Plan B production company and Paramount Pictures in 2010. The adaptation, directed by James Gray, who also wrote the screenplay,[11] premiered on October 15, 2016, at the 54th New York Film Festival. The film stars Charlie Hunnam as Percy Fawcett, Sienna Miller as Fawcett's wife, Tom Holland as Jack Fawcett and Robert Pattinson as Henry Costin.[12]

Editions

- Grann, David (2009). The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51353-1. A paperback edition was released in January 2010.

- As of this date, The Lost City of Z has been translated into more than 25 languages.

See also

- Brazilian Adventure (1933), by Peter Fleming, travel literature about a search for Fawcett

- Road to Zanzibar (1941), movie loosely based on the search for Fawcett

- Indiana Jones and the Seven Veils (1991), Indiana Jones novel with a plot to find Fawcett

Further reading

- Col. P. H. Fawcett (1953). Lost Trails, Lost Cities. Selected and arranged from his manuscripts, letters, and other records by Brian Fawcett. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Co. LCCN 53006980. OL 6134053M.

- Grann, David (September 19, 2005). "The Lost City of Z". The New Yorker. LXXXI (28): 56–81. ISSN 0028-792X.

- Langer, Johnni (2002). "A Cidade Perdida da Bahia: mito e arqueologia no Brasil Império". Revista Brasileira de História (in Portuguese). 22 (43): 126–152. doi:10.1590/S0102-01882002000100008. ISSN 1806-9347.

References

- David Grann, Lost City of Z, 2009, pp. 270–72

- Hemming, John (1 April 2017). "The Lost City of Z is a very long way from a true story and I should know". The Spectator.

- Biello, David. (August 28, 2008). "Ancient Amazon Actually Highly Urbanized", Scientific American.

- Cohen, Rich. (February 26, 2009)."On the Road to El Dorado." The New York Times.

- Kakutani, Michiko. (November 26, 2009). "Michiko Kakutani's Top 10 Books of 2009." The New York Times.

- Kakutani, Michiko. (March 16, 2009). "An Explorer Drawn to, and Eventually Swallowed by, the Amazon." The New York Times.

- Arana, Marie. (March 6, 2009). "Lost in the Jungle." Washington Post.

- Winchester, Simon. (February 27, 2009). "The Endless Allure of El Dorado." Wall Street Journal.

- Thomson, Hugh. "The hero of ‘The Lost City of Z’ was no hero", Washington Post, April 12, 2009.

- Hemming, John. "Gung ho ho. 'Lost City of Z, The' by Grann, David (author)", The Times Literary Supplement. June 05, 2009; pg. 7-8; Issue 5540.

- "The Immigrant: James Gray on Being Beloved By the French". CraveOnline. 2014-05-14. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- Dockterman, Eliana (February 4, 2015). "Charlie Hunnam Replaces Benedict Cumberbatch in The Lost City of Z". Retrieved May 3, 2015.

External links

- Official website

- Excerpt of the first chapter in The Wall Street Journal

- "The search for a mythical lost city", NPR interview with David Grann

- Anonymous. Manuscript 512 (1754), about the first expedition to The Lost City (Portuguese).

- (Video) The Lost City of Z, author interview on Fora.tv