The Tragedy of Arthur

The Tragedy of Arthur is a 2011 novel by the American author Arthur Phillips. The narrative concerns the publication of a recently discovered Arthurian play attributed to William Shakespeare, which the main narrator, "Arthur Phillips", believes to be a forgery produced by his father. It was published by Random House.

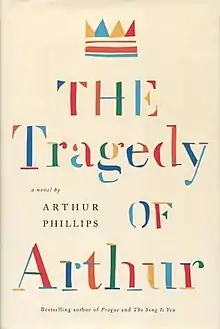

First edition | |

| Author | Arthur Phillips |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Random House |

Publication date | April 27, 2011 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 368 pp |

| ISBN | 0-8129-7792-0 |

The book takes the form of an edition of the play The Tragedy of Arthur, along with an extensive introduction and footnotes by Phillips, and additional notes by the publishers who argue for the play's authenticity. The introduction also serves as a memoir of the protagonist as he tells the story of his family and their connection to the apocryphal text.

Critics have reviewed the book positively. It was shortlisted for the International Dublin Literary Award.[1]

Synopsis and text

Preface

The book opens with a Preface by the editors of Random House, introducing the text as the "first modern edition of The Tragedy of Arthur by William Shakespeare." It provides a brief summary of the Shakespearean canon and Apocrypha, claiming that The Tragedy of Arthur is "the first certain addition to Shakespeare's canon since the seventeenth century."[2] They also thank Professor Roland Verre for his research confirming the play's authenticity, as well as Peter Bryce, David Crystal, Tom Clayton, and Ward Elliott for their efforts. Finally, the Preface thanks Arthur Phillips for writing an Introduction, as well as for editing and annotating the text of the play. However, Random House strongly recommends that readers read the play before the introduction, "allowing Shakespeare to speak for himself, at least at first", before perusing Phillips' "very personal Introduction" or "the many other commentaries sure to be available soon".

Introduction

The Introduction is written by Arthur Phillips, a fictionalized version of Arthur Phillips, who opens the Introduction by admitting that he "never much liked Shakespeare."[3] Phillips qualifies his lack of interest in the Bard, and notes that The Tragedy of Arthur could plausibly be the work of Shakespeare, as it is "as good as most of his stuff, or as bad." Even though Phillips admits that he is not a memoirist, and his reputation may be damaged by this story, he insists that: "to understand this play, its history, and how it came to be here, a certain quantity of [his] autobiography is unavoidable."

From there, the rest of the Introduction serves as a memoir of the fictional Arthur Phillips, his twin sister, Dana, and their father, A.E.H. Phillips, a con artist and Shakespeare enthusiast who was in and out of prison for their entire childhood. The twins are raised in Minneapolis, and from an early age, their father tries to get them interested in Shakespeare – Arthur remains ambivalent, while Dana is immediately hooked. Arthur narrates their childhood, regularly interrupting himself to apologize for any lapses in memory or "falling prey to the distortions of memoir writing.".[4] A.E.H. Phillips continues to be in and out of jail amidst various schemes, from petty coupon scams to forging signatures on fake Rembrandt paintings. Arthur and Dana's parents ultimately divorce, and their mother marries a man named Silvius diLorenzo, with whom she had had a brief relationship in college.

The Introduction is more about Arthur's father than anything else - A.E.H. Phillips "continually shoves his way to the foreground, wherever [Arthur turns] memory's camera."[5] Arthur's relationship to his father is strained – he points out that his father, through Shakespeare, "took [his] best friend, Dana, away from" him.[6] Arthur spends much of the Introduction trying to describe his father despite his limited presence in his son's life, both through tropes – "the Anglophilic, artsy, bohemian Jew" despite not being "interested in himself as a Jew at all, but by no means interested in anonymity"[7] – as well as through personal anecdotes. He claims that his father was interested in the proliferation of mystery and "wonder", rather than cold hard facts, as he sought to redeem "the world's vanishing faith in wonder".[8]

"I admit that this seems a long way from an Introduction to a newly discovered Shakespeare play; this essay is fast becoming an example of that most dismal genre, the memoir. All I can say is that the truth of the play requires understanding the truth of my life."

— Arthur Phillips, The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 35

Arthur and Dana first become aware of The Tragedy of Arthur at age eleven, when their father gives them a red hardcover edition of the play, dated 1904, with inscriptions to Arthur Donald "Don" Phillips (Arthur's grandfather) dated 1915, and to A.E.H. Phillips, dated 1942. Upon sharing it with his children, A.E.H. Phillips tells them that its status within the Shakespeare canon is disputed, and insists that they read the play and make up their own minds about the play's veracity. Dana is much more interested in the text than Arthur – it is the only Shakespeare play she hadn't read – and is allowed to borrow it and talk about it, but not make copies or lend it to anyone. A.E.H Phillips ultimately gives the 1904 hardcover to her – "April 22, 1977 For my Dana on her 13th birthday" – in addition to an advertisement for a 1930s London stage production of Shakespeare's Tragedy of King Arthur starring Errol Flynn as Arthur and Nigel Bruce as Gloucester.[9] ("Don't rush to Google that one," Arthur Phillips notes in his narration.)

Over the years, Dana and A.E.H. Phillips speculate about the origin of the play and propose various explanations for the text's rarity and exclusion from the canon (one theory considers the play as having been written for a secret lover who rejected it). In 1979, however, A.E.H. begins serving a ten-year prison sentence for one of his schemes, and as an act of rebellion, Dana becomes an anti-Stratfordian. To insult her father and his lifelong love of Shakespeare, she spends several years – including her time at Brown – developing her own Shakespearean authorship theory, one that posited the works of "William Shakespeare" as the product of two men – Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford and the son of a Jewish moneylender. She quickly abandons this theory upon graduating college in 1986, but "was converted by the fire of her experience into a lover of works, not authors." [10]

A.E.H. Phillips spends most of the next decade in prison, while Dana finds work acting for theater companies in New York City, and Arthur follows her to be a copywriter for an ad agency, and ultimately a freelance writer. He spends several years in Europe, having fled his "father", "mother", "twin", "work" and "an entire life, which [he] at twenty-eight dismissed as unoriginal and a failure".[11] He settles down and marries a Czech woman named Jana, and his twin sons are born in 1995; he remains in Prague until 2009, publishing four novels in that time. He returns to the United States sporadically, first to visit Dana and his father upon his release from prison, and then again when "Sil", his stepfather, dies. At this point Dana has moved back to Minneapolis and is thriving as a high school drama teacher and a successful actor in local theaters, and when he returns for Sil's funeral, he becomes obsessed ("something rarer than mere lust but that no twenty-first-century grown-up can dare call by its proper name: 'love at first sight'"[12]) with his sister's girlfriend, Petra.

On this latter trip, he also meets up with his father, imprisoned again, who fervently insists that Arthur help him with a project. A.E.H. Phillips directs his son to a safe-deposit box, and Arthur reluctantly obliges, enlisting Petra to help him. The safe-deposit box – which, they're told, hadn't been opened in 23 years – contains a quarto edition of The Tragedy of Arthur – with Shakespeare's name on the title page – dated 1597. They bring the quarto back to Petra and Dana's apartment and pore over it, Petra and Dana excited, Arthur intrigued and skeptical. Arthur quickly concludes that it "was obviously a Shakespeare play because these two women [he] loved so differently each loved it so much the same."[13] In spite of Dana's confidence as to its veracity, Arthur gets in contact with his father, who assures him of its authenticity, and instructs him to confirm it using modern scientific techniques and scholarship. Arthur agrees to follow his father's instructions to publish the play, but remains confused about why his father enlisted his help, rather than Dana's. He notifies his family (back in Prague) that he has to stay in Minneapolis in order to complete this project.

Unable to find any reference to the play – or any other copies of the 1904 hardcover edition – on the internet, Arthur meets with his father in person to learn about the quarto's origin. A.E.H Phillips claimed that, in 1958, he travelled to England to "do some work for a wealthy client."[14] In this client's enormous country house, he found a series of homemade anthologies featuring self-bound quartos of plays by Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and others, and in one of these A.E.H. Phillips found a 1597 quarto (unlisted in the table of contents) that he had never heard of, credited to Shakespeare. Upon reading the play through and through, he decided that the play was undeniably the work of Shakespeare, stole the quarto out of the book using nail scissors, and brought it back to Minnesota. A.E.H. Phillips claims that while, in his research, he found no reference to the play whatsoever, he maintained his certainty that it was real. He admits to creating the 1904 edition (as a travel copy, for himself) and the Errol Flynn poster (as a gift to Dana), but continues to insist that the quarto is real, and not one of his cons.

Arthur's father insists that Arthur has to get the play published so that Arthur, Dana, and their mother can profit immensely from it. He wants Arthur to claim the quarto was found by Sil in an attic in the 1950s, and to verify that nobody else would have a claim to the text (namely, the estates of the printer and publisher, William White and Cuthbert Burby). A.E.H. Phillips reveals that he is dying, and, with Dana and Petra's encouragement, Arthur agrees to carry out this last request in spite of his lifelong distrust of his father.

Arthur proceeds to get the play verified and published, with Random House shouldering the burden of the authentication process. When his editor offers to take the play out of his hands, Arthur insists that it's his family's project, and he wants to be a part of it, and is tasked with writing the play's Introduction. He begins to believe that, without question, The Tragedy of Arthur was written by William Shakespeare, and as he works on the publication of the text, Arthur remains preoccupied with Petra, and ultimately starts sleeping with her despite her relationship with Dana. After his father's death, however, Arthur discovers an index card with details of the play on it, and becomes convinced that it's evidence that the play is a forgery. Furthermore, his father's will dictates that the profit from the publication of the quarto be divided between Arthur, Dana, their mother, and his former business associate, Charles Glassow. The will also requires that the play be published as the work of William Shakespeare, and that any effort made by Arthur to dispute the play's authenticity will result in his share of the profits being forfeited.

Refusing to believe that the play is real in the wake of this discovery, Arthur tries to get Random House to call off the project, but they refuse: forensic and historical evidence has all but confirmed the play's veracity, and they claim that the ambiguous "clues" on this index card prove nothing against the word of numerous Shakespeare experts. He continues to argue with his publishers and Dana – who insists that the play is real – and is ultimately threatened with breach of contract if he stands in the way of the play's publication. Ultimately, Dana (having found out about Petra's affair with Arthur) confronts him and demands that he allow the play to be published, and instructs him to write an Introduction – "the truth… for once in [his] life" – and "be judged for what [he] did."[15]

The Introduction closes with Arthur – still refusing to claim that the play is real – facilitating its publication anyway. Arthur meditates on the artificiality of endings, and points out that the reader's reaction to The Tragedy of Arthur rests on how they interpret the story told in the Introduction. He sums up the project by claiming that those "who know [him] personally know to a fine degree how much of all this is true, how much an apology (and how sincere), how much a boast or a con job. To the rest of you, it's a muddle or it's a thing of beauty. And if it pleased you, and you found in its candor and lies and sobbing cross-dressed confessions some hours' entertainment, then well and good."[16]

The Tragedy of Arthur (play)

.jpg.webp)

The Most Excellent and Tragical Historie of Arthur, King of Britain (more widely known as The Tragedy of Arthur) is a play, represented as having been written by William Shakespeare, uncovered in 2010 by Arthur Phillips. The first edition of it was published in 2011 by Random House.[17] It tells the story of the legendary King Arthur, who is described in the Introduction to play's first edition by Phillips as "a charismatic, charming, egocentric, short-tempered, principled but chronically impulsive bastard."[18] The play narrates his victories and failures as King of Britain.

The English-Welsh Court

- Arthur, Prince of Wales, later King of Britain

- Duke of Gloucester, Arthur's guardian, later adviser

- Constantine, Earl of Cornwall, later King of Britain

- 'Guenhera, his sister, later Queen of Britain

- Duke of Somerset

- Duke of Norfolk

- Earl of Cumbria

- Earl of Kent

- Sir Stephen of Derby

- Bishop of Caerleon

- Lady Crier and other Ladies of the court

- Guenhera's Nurse

The Pictish-Scottish Court

- Loth, King of Pictland

- Mordred, Loth's son, Duke of Rothesay, later King of Pictland

- Calvan, Mordred's brother, Prince of Orkneys

- Coranus, King of Scotland

- Alda, Queen of Scotland, sister-in-law to Loth, aunt to Mordred and Arthur

- Duke of Hebrides, son to Conranus

- Alexander, a messenger

- Doctor

in addition to:

- Colgerne, chief of the Saxons

- Shepherdess

- Master of the Hounds

- The Master of the Hounds' Boy

- Denton, an English soldier

- Sumner, an English soldier

- Michael Bell, a young English soldier

- French Ambassador

- Philip of York

- Player King

- Player Queen

- Messengers, Servants, Huntsmen, Attendants, Trumpeters, Hautboys, Soldiers, Players

Plot

"Contractually bound" to provide a synopsis of the play,[19] Phillips sketches out descriptions of the play's five acts in the Introduction, relating the details of them to details of his family history. Professor Roland Verre, who co-edited the play, offers a more effective summary preceding the text, in addition to many explanatory footnotes throughout.

Act I opens in sixth-century Britain, with Arthur, the product of rape between King Uter Pendragon and a noble's wife, in Gloucestershire, far from his father's wars against the Saxons. Arthur inherits the throne upon his father's death, but his right is challenged by Morded, heir to the crown of Pictland, who claims dominion over all of Britain. Morded's father, King Loth, refuses to honor his son's wishes through war, but Morded provokes one anyway.

In Act II, Arthur gains his first major military victory against the Saxons, Picts, and Scots. After the battle, Arthur sends his army, led by the Duke of Gloucester, in pursuit of Mordred, and Gloucester (disguised as Arthur) wins a great victory against the remaining Saxon forces. Arthur arrives to the battle late, and spares his enemies in exchange for the promise of peace, but retains Mordred's brother as ransom. When the Saxons betray this peace, Arthur kills all prisoners (including the hostage brother) in a rage, while Mordred becomes King of Pictland and vows revenge against Arthur.

Act III finds Gloucester arranging a marriage for Arthur with a French princess that would guarantee wealth, allies, and help him achieve his goal of a unified, peaceful, and prosperous Britain. Ignoring this arrange wedding, Arthur marries Guenhera, the sister of a friend, who had loved him since childhood. She miscarries twice, and Arthur's nobles complain that he no longer has the mettle for military matters, and has turned the court into a place of effeminate recreation and artistic endeavors (one of these nobles considers assassinating Arthur to stop this).

In Act IV, Guenhera is pregnant again, and has effectively seized control, as Arthur has become completely submissive to her. The Saxons attack yet again, and Arthur realizes that he does not have the means to defend his kingdom, and that, through his rash decisions, no longer has the French and Picts as allies. He negotiates for Pictish aid by naming Mordred his heir, and Mordred assists in the victory of the Saxons at Linmouth.

Act V finds Mordred traveling to London while Arthur is away (fighting an Irish rebellion), where he finds out that Guenhera has miscarried again, but that the throne has been promised to one of Arthur's illegitimate children, Philip of York. Furious at Arthur's deception, Mordred kidnaps Guenhera and Philip. Arthur receives news of this and meets Mordred to battle near the Humber River - fighting breaks out, and Mordred murders Guenhara and kills Gloucester in battle. Arthur, devastated, comes to realize his flaws as a regent and kills Mordred, dying in the process, as a new king of unified Britain is crowned.

Authenticity

Despite Arthur Phillips' insistence otherwise, the play is verified as authentically Shakespearean by many experts. Linguist David Crystal muses that it is "probably a collaboration", and claims that it was written no later than 1595, and possibly dates from before 1593.[20] Tests conducted by Peter Bryce at the chemistry lab at the University of Minnesota indicated the veracity of the paper as genuinely from the 1590s - something that Bryce insist could not be forged. The Shakespeare Clinic at Claremont College also confirmed through stylometry systems that Arthur "scores the closest match to core Shakespeare since the foundation of the Clinic".[21] Scholarly consensus puts the play as contemporaneous with the Shakespeare of the early to mid-1590s, around the time of Henry VI, Part 3 and Richard III.

While there is some skepticism (most notably from Arthur Phillips himself), it would have been remarkably difficult for A.E.H. Phillips to have constructed a forgery to fool all modern forensic evidence and Shakespeare scholars, especially given the quarto would necessarily have to predate much of the technology and research used to check its authenticity. Even though Phillips claims that the play is the work of his father, most Shakespeare scholars have discounted his theory. The only copy of the 1594 quarto of Titus Andronicus was discovered in an attic in Sweden in 1904, and so the bizarre means by which Arthur has been lost for centuries seem relatively plausible.

Background

Phillips has freely admitted that he is the author of the play, though upon its release, he did, from time to time, remain "in character" while promoting the book.[22] He has articulated in interviews that he likes to "play along" and maintain the mystery of the truth behind the book and play.[23] Phillips has also said that writing the play and Introduction was "the most fun [he's] ever had doing anything."[24]

Phillips claims that before this project, he had only a passing familiarity with Shakespeare as a product of his education. Before embarking upon this endeavor, Phillips did extensive research, including thoroughly investing himself in Shakespeare's complete works. In this research, Phillips "fell in love with" Shakespeare's work, even though he maintains a resistance to what he calls "bardolatry" or "the constant search for proof that he was wiser, more powerful, more obviously the best than anyone else ever"[25] (the same "Shakespeare cult" that the fictional Phillips complains about throughout the Introduction).

In writing, he claims that "The play came first, in every draft. Within the novel, the chronology goes: play discovered, play discussed. So, I needed a play to discuss, therefore I had to write the play first."[26] He spent four years writing the novel.[27] Phillips also claims that the novel's interest in memoir came from his belief that "memoir, done correctly, is not fiction."[28] In writing The Tragedy of Arthur, he sought to call into question the way we think about fiction vs. non-fiction, as well as what makes something supposedly "real".

Themes

The book constantly blurs the lines between fiction and reality – the Arthur Phillips that narrates the Introduction is "the internationally bestselling author of Prague, The Egyptologist, Angelica, and The Song as You,"[29] as well as the author of a review of Milan Kundera's The Curtain for Harper's.[30][31] However, the narrator is not the same person as the novelist, Arthur Phillips; for example, as the author has pointed out, his family "doesn't resemble" that of the character.[32] This is a coy move on Phillips' part, as he never bears the burden of telling the whole truth – he constantly points out the unreliability of memoir as a form, acknowledging that it is "despite [his] best efforts, already misleading".[33] The novel also references James Frey, who faced scandal when it was revealed that his drug-addiction "memoir" A Million Little Pieces was a work of fiction. (Frey is also quoted on Phillips' website as having enjoyed the book.)[34]

The Tragedy of Arthur also brings into play questions of authorship akin to those raised by critical theorists Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault, in their essays "Death of the Author" and "What is an Author?". Foucault's question – "What does it matter who is speaking?" – and his concept of "The Author Function" is essential to the protagonist's investigation into – and evaluation of – the works his father produces.[35]

The Tragedy of Arthur operates in the tradition of other works, such as Vladimir Nabokov's Pale Fire, Mark Z. Danielewski's House of Leaves, Lemony Snicket's writings, and Orson Welles' "documentary" F For Fake in how it distorts reader expectations as far as "fiction" and "truth." A.E.H. Phillips' schemes also include art forgery, and the novel references the van Meegeren Vermeer forgeries. In particular, it shares a structural similarity to Pale Fire, which is a novel in the form of a foreword to and commentary on a poem by the fictional John Shade by an academic colleague. Like Pale Fire, The Tragedy of Arthur is also a satire of academia, though Phillips' novel, of course, focuses its parody specifically on Shakespeare studies.

To wit, the novel is deeply invested in exploring Shakespeare scholarship and the "Shakespeare-Industrial Complex"[36] - in particular the work of Harold Bloom, whose books The Anxiety of Influence and Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human are explicitly referenced. The Introduction features countless references to Shakespeare plays, many of which, Phillips claims were unintentional, artifacts of "things that stuck in memory" from his research.[37] The book also references the grand scope of Shakespeare's influence – the narrator claims that his writing is "a nursery of titles for other, better writers" going on to list Pale Fire, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, Infinite Jest, The Sound and the Fury and many other texts. Furthermore, the novel is remarkably dismissive of the anti-Stratfordian (i.e., those who do not believe that a man named William Shakespeare wrote the plays attributed him) camp of Shakespeare scholarship. Phillips calls their theories "a gentle, harmless madness," and as plausible as the narrative of Roland Emmerich's Independence Day (Emmerich directed the 2011 anti-Stratfordian film Anonymous). He immersed himself in their argumentation in researching the book and "came to the conclusion that while [he] can appreciate their passion and their willingness to hold on against a sometimes-scornful majority, they are really, really just wrong. Their approach to factual documentation and to the reading of fiction, both, require a view of the universe that [he] just can’t accept."[38] Even so, Phillips maintains that "the deification gets in the way of what [Shakespeare is] actually good at," and that his critique of "Bardolatry" in the novel is equally in earnest.[39]

Critical reception

The Tragedy of Arthur was well-received, and was lauded as one of the best books of 2011 by The New York Times,[40] The Wall Street Journal,[41] The Chicago Tribune,[42] Salon,[43] The New Yorker,[44] NPR,[45] and others.

Furthermore, the "authenticity" of the forged play has been praised by several notable Shakespearean scholars. Stephen Greenblatt, in his review for The New York Times, claimed that the play "is a surprisingly good fake… much of 'The Tragedy of Arthur' actually sounds as if it could have been written by the author not of 'Hamlet,' to be sure, but of 'The True Tragedy of Richard, Duke of York.' This is no trivial achievement; it is the work of a very gifted forger."[46] Greenblatt claims that "It is a tribute to Arthur Phillips’s singular skill that his work leaves the reader not with resentment at having been tricked but rather with gratitude for the gift of feigned wonder." James S. Shapiro, author of Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? called it a "brilliant piece of literary criticism masquerading as a novel," claiming that it was "the most ambitious book on Shakespeare [he has] come across in many years because it so deeply engages questions that matter."[47]

Adaptations

The New York City-based theater troupe Guerilla Shakespeare Project produced a stage version of The Tragedy of Arthur in 2013 with Phillips' involvement.[48] It opened to mixed reviews.[49][50]

References

- "IMPAC Dublin Literary Award shortlist announced", December 4, 2012

- Arthur Phillips, The Tragedy of Arthur. 1st ed. New York: Random House, 2011.

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 1

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 35

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 36

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 32

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 10

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 17

- The Tragedy of Arthur, pp. 32-33

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 76

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 113

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 128

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 148

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 156

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 251

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 255

- Random House: The Tragedy of Arthur

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 9

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 42

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 190

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 227

- "Interview with Arthur Phillips", Full Stop, June 29, 2011

- "The Exchange: Arthur Phillips", The New Yorker, June 13, 2011

- Robert Birnbaum, "Arthur Phillips, Redux", The Morning News, June 16, 2011.

- "The Exchange: Arthur Phillips", The New Yorker, June 13, 2011

- "The Exchange: Arthur Phillips", The New Yorker, June 13, 2011

- Noah Charney, "How I Write: 'The Tragedy of Arthur' by Arthur Phillips", The Daily Beast, August 22, 2012.

- "The Exchange: Arthur Phillips", The New Yorker, June 13, 2011

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 1

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p.12

- Arthur Phillips, "The disillusionist: In praise of Milan Kundera's hypocrisy", Harper's nagazine, March 2007.

- Robert Birnbaum, "Arthur Phillips, Redux", The Morning News, June 16, 2011.

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p. 36

- Foucault, "What is an Author?"

- The Tragedy of Arthur, p.95

- "Interview with Arthur Phillips", Full Stop June 29, 2011

- "The Exchange: Arthur Phillips", The New Yorker, June 13, 2011

- "Interview with Arthur Phillips", Full Stop, June 29, 2011

- "100 Notable Books of 2011", The New York Times, November 21, 2011

- "The Best Fiction of 2011" The Wall Street Journal, December 17, 2011

- "The Chicago Tribune's favorite books of 2011"

- "The best fiction of 2011", Salon.com, December 6, 2011

- "A Year's Reading", The New Yorker, December 19, 2011

- Heller McAlpin, "A Faux Folio At The Heart of 'The Tragedy Of Arthur'", NPR, April 19, 2011.

- Stephen Greenblatt, "Shakespeare and the Will to Deceive", The New York Times, April 28, 2011.

- James Shapiro, "The Tragedy of Arthur by Arthur Phillips: Review", The Daily Beast, April 27, 2011.

- Guerilla Shakespeare Project

- "Blog Wrapper", Guerilla Shakespeare Project

- Deirdre Donovan, "A CurtainUp Review:The Tragedy of Arthur", CurtainUp