Thirty Years' War

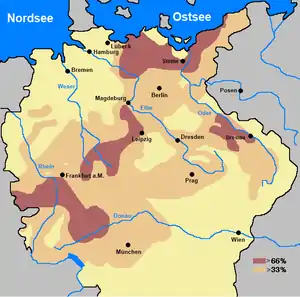

The Thirty Years' War (German: Dreißigjähriger Krieg, pronounced [ˈdʁaɪ̯sɪçˌjɛːʁɪɡɐ kʁiːk] (![]() listen)) was a conflict primarily fought in Central Europe from 1618 to 1648. Estimates of total military and civilian deaths range from 4.5 to 8 million, mostly from disease or starvation. In some areas of Germany, it has been suggested that up to 60% of the population died.[17]

listen)) was a conflict primarily fought in Central Europe from 1618 to 1648. Estimates of total military and civilian deaths range from 4.5 to 8 million, mostly from disease or starvation. In some areas of Germany, it has been suggested that up to 60% of the population died.[17]

Until the mid-20th century, it was seen as predominantly a German civil war or was considered one of the European wars of religion. In 1938, C. V. Wedgwood argued it formed part of a wider European conflict, whose underlying cause was the ongoing contest between Austro-Spanish Habsburgs and French Bourbons. This view is now generally accepted by historians.[18] Related conflicts include the Eighty Years War, the War of the Mantuan Succession, the Franco-Spanish War, and the Portuguese Restoration War.

The conflict can be split into two main parts. The first period, from 1618 to 1635, was a struggle within the Holy Roman Empire fought between Emperor Ferdinand II and his internal opponents, with external powers playing a supportive role. Despite the parties agreeing on the Peace of Prague in 1635, fighting continued with Sweden and France on one side, the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs on the other. This second phase ended with the 1648 Peace of Westphalia.

The war originated in differences between German Protestants and Catholics, which were temporarily settled by the 1555 Peace of Augsburg but was gradually undermined by political and religious tensions. In 1618, the Bohemian Estates deposed the Catholic Ferdinand II as King of Bohemia. They offered the Crown to the Protestant Frederick V of the Palatinate, who accepted. Regardless of religion, most German princes refused to support him, and by early 1620, the Bohemian Revolt had been suppressed.

When Frederick refused to admit defeat, the war expanded into the Palatinate, whose strategic importance drew in external powers, notably the Dutch Republic and Spain. By 1623, Spanish-Imperial forces controlled the Palatinate. Backed by the Catholic League, Ferdinand stripped Frederick of his possessions and sent him into exile. This threatened other Protestant rulers within the Empire, including Christian IV of Denmark, who was also Duke of Holstein. In 1625, he intervened in Northern Germany but withdrew in 1629 after a series of defeats.

Bolstered by this success, Ferdinand passed the Edict of Restitution, which undermined territorial rights across large areas of North and Central Germany. This provided an opportunity for Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, who invaded the Empire in 1630. Backed by French subsidies, the Swedes and their German allies won a series of victories over Imperial forces, although Gustavus was killed in 1632. In 1635, Ferdinand made peace with his German opponents by accepting their autonomy. In return, they dissolved the Heilbronn and Catholic Leagues.

The defection of their German allies led France to join the war directly, which continued until Westphalia in 1648. Its main provisions included Spanish confirmation of Dutch independence and acceptance of "German liberties" by the Austrian Habsburgs. By weakening the Habsburgs while increasing the status of France and Sweden, it led to a new balance of power on the continent.

Structural origins

The 1555 Peace of Augsburg was intended to end conflict between German Protestants and Catholics by establishing the principle of cuius regio, eius religio. This meant each of the 224 member states was either Lutheran, the most usual form of Protestantism, or Catholic, based on the choice made by their ruler. In addition, Lutherans could keep lands or property taken from the Catholic Church since the 1552 Peace of Passau. However, it was a compromise that failed to resolve underlying religious and political tensions within the Holy Roman Empire.[19]

After 1560, the Protestant cause was deeply divided by the growth of Calvinism, a Reformed faith not recognised by Augsburg; Lutheran states like Saxony viewed Calvinists in the Palatinate and Brandenburg with mistrust, paralysing Imperial institutions.[20] In addition, rulers might share the same religion but have different economic and strategic objectives; for much of the war, the Papacy supported France against the Habsburgs. The chief agents of the Counter-Reformation were similarly split, the Jesuits generally backing Austria, the Capuchins France.[21]

Managing these issues was complicated by the fragmented nature of the Empire, a patchwork of nearly 1,800 separate entities in Germany, the Low Countries, Northern Italy, and areas like Alsace, now part of modern France. They ranged in size and importance from the seven Prince-electors who voted for the Holy Roman Emperor, down to Prince-bishoprics and City-states, such as Hamburg. Each member was represented in the Imperial Diet; prior to 1663, this assembled on an irregular basis, and was primarily a forum for discussion, rather than legislation.[22]

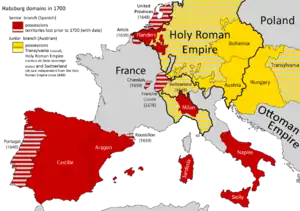

While Emperors were elected, since 1440 this had been a Habsburg, the largest single landowner within the Empire; their lands included the Archduchy of Austria, the Kingdom of Bohemia, and the Kingdom of Hungary, with over eight million subjects. In 1556, Habsburg Spain became a separate entity, while retaining Imperial states such as the Duchy of Milan, and interests in Bohemia and Hungary; the two often co-operated, but their objectives did not always align. Then the predominant global power, the Spanish Empire included the Spanish Netherlands, much of Italy, the Philippines, and most of the Americas, while Austria remained focused on Central Europe.[23]

Before Augsburg, unity of religion compensated for lack of strong central authority; once removed, it presented opportunities for those who sought to further weaken it. This included ambitious Imperial states like Lutheran Saxony and Catholic Bavaria, as well as France, which faced Habsburg territories on its borders in Flanders, Franche-Comté, and the Pyrenees. Disputes within the Empire drew in outside powers, many of whom held Imperial territories, including the Dutch Prince of Orange, hereditary ruler of Nassau-Dillenburg. Christian IV of Denmark was also Duke of Holstein, and it was in this capacity he joined the war in 1625.[24]

Background; 1556 to 1618

These tensions gradually undermined Augsburg, and paralysed institutions like the Imperial diet designed to resolve them peacefully. Occasionally it meant full-scale conflict, such as the 1583 to 1588 Cologne War, caused by the conversion to Calvinism of the Prince Elector, Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg. More common were disputes such as the 1606 'Battle of the Flags' in Donauwörth, when the Lutheran majority blocked a Catholic religious procession. Emperor Rudolf approved intervention by the Catholic Maximilian of Bavaria on their behalf. To recover his costs, Maximilian was allowed to annex Donauwörth, which under the principle of cuius regio, eius religio changed a formerly Lutheran town into a Catholic one.[25]

As a result, when the Imperial Diet opened in February 1608, the Protestants demanded formal confirmation of the Augsburg settlement, which was especially significant for Calvinists like Frederick IV, Elector Palatine who had not been included. The Habsburg heir Archduke Ferdinand first required the return of all property taken from the Catholic church since 1552, rather than leaving the courts to decide case by case as previously. This threatened both Lutherans and Calvinists, paralysed the Diet, and removed the perception of Imperial neutrality.[26]

Frederick IV now formed the Protestant Union, largely composed of states in Southern Germany, to which Maximilian responded by setting up the Catholic League in July 1609. While both Leagues were primarily designed to support the dynastic ambitions of their leaders, their creation combined with events like the 1609 to 1614 War of the Jülich Succession to increase tensions throughout the Empire.[27] Some historians who see the war as primarily a European conflict argue Jülich marks its beginning, with Spain and Austria backing the Catholic candidate, France and the Dutch Republic the Protestant.[28]

.png.webp)

Outside powers became involved in an internal German dispute due to the imminent expiry of the 1609 Twelve Years' Truce, which suspended the war between Spain and the Dutch. Before restarting hostilities, Ambrosio Spinola, commander in the Spanish Netherlands, had first to secure the Spanish Road, an overland route connecting Habsburg possessions in Italy to Flanders. This allowed Spinola to move troops and supplies by road, rather than sea where the Dutch navy held the advantage and by 1618, the only part not controlled by Spain ran through the Electoral Palatinate.[29]

Since Emperor Matthias had no surviving children, in July 1617 Philip III of Spain agreed to support Ferdinand's election as king of Bohemia and Hungary. In return, Ferdinand made concessions to Spain in Northern Italy and Alsace, and agreed to support their offensive against the Dutch. Delivering these commitments required his election as Emperor, which was not guaranteed; one alternative was Maximilian of Bavaria, who opposed the increase of Spanish influence in an area he considered his own, and tried to create a coalition with Saxony and the Palatinate to support his candidacy.[30]

Another was Frederick V, Elector Palatine, who succeeded his father in 1610, and in 1613 married Elizabeth Stuart, daughter of James I of England. Four of the electors were Catholic, three Protestant; if this could be changed, it might result in a Protestant Emperor. When Ferdinand was elected king of Bohemia in 1617, he gained control of its electoral vote; however, his conservative Catholicism made him unpopular with the largely Protestant Bohemian nobility, who were also concerned at the erosion of their rights. In May 1618, these factors combined to bring about the Bohemian Revolt.[31]

Phase I: 1618 to 1635

The Bohemian Revolt

The Jesuit educated Ferdinand once claimed he would rather see his lands destroyed than tolerate heresy for a single day. Appointed to rule the Duchy of Styria in 1595, within eighteen months he eliminated Protestantism in what was previously a stronghold of the Reformation.[32] Focused on retaking the Netherlands, the Spanish Habsburgs preferred to avoid antagonising Protestants elsewhere, and recognised the dangers associated with Ferdinand's fervent Catholicism, but accepted the lack of alternatives.[33]

Ferdinand reconfirmed Protestant religious freedoms when elected king of Bohemia in May 1617, but his record in Styria led to the suspicion he was only awaiting a chance to overturn them. These concerns were exacerbated when a series of legal disputes over property were all decided in favour of the Catholic Church. In May 1618, Protestant nobles led by Count Thurn met in Prague Castle with Ferdinand's two Catholic representatives, Vilem Slavata and Jaroslav Borzita. In an event known as the Second Defenestration of Prague, the two men and their secretary Philip Fabricius were thrown out of the castle windows, although all three survived.[34]

Thurn established a new government, and the conflict expanded into Silesia and the Habsburg heartlands of Lower and Upper Austria, where much of the nobility was also Protestant. One of the most prosperous areas of the Empire, Bohemia's electoral vote was also essential to ensuring Ferdinand succeeded Matthias as Emperor, and Habsburg prestige required its recapture. Chronic financial weakness meant prior to 1619 the Austrian Habsburgs had no standing army of any size, leaving them dependent on Maximilian and their Spanish relatives for money and men.[35]

Spanish involvement inevitably drew in the Dutch, and potentially France, although the strongly Catholic Louis XIII faced his own Protestant rebels at home and refused to support them elsewhere. It also provided opportunities for external opponents of the Habsburgs, including the Ottoman Empire and Savoy. Funded by Frederick and the Duke of Savoy, a mercenary army under Ernst von Mansfeld succeeded in stabilising the Bohemian position over the winter of 1618. Attempts by Maximilian of Bavaria and John George of Saxony to broker a negotiated solution ended when Matthias died in March 1619, since it convinced many the Habsburgs were fatally damaged.[36]

By mid-June, the Bohemian army under Thurn was outside Vienna; Mansfeld's defeat by Spanish-Imperial forces at Sablat forced him to return to Prague, but Ferdinand's position continued to worsen.[37] Gabriel Bethlen, Calvinist Prince of Transylvania, invaded Hungary with Ottoman support, although the Habsburgs persuaded them to avoid direct involvement, helped by the outbreak of hostilities with Poland in 1620, followed by the 1623 to 1639 war with Persia.[38]

On 19 August, the Bohemian Estates rescinded Ferdinand's 1617 election as king, and on 26th, formally offered the crown to Frederick instead; two days later, Ferdinand was elected Emperor, making war inevitable if Frederick accepted. With the exception of Christian of Anhalt, his advisors urged him to reject it, as did the Dutch, the Duke of Savoy, and his father-in-law James. 17th century Europe was a highly structured and socially conservative society, and their lack of enthusiasm was due to the implications of removing a legally elected ruler, regardless of religion.[39]

As a result, although Frederick accepted the crown and entered Prague in October 1619, his support gradually eroded over the next few months. In July 1620, the Protestant Union proclaimed its neutrality, while John George of Saxony agreed to back Ferdinand in return for Lusatia, and a promise to safeguard the rights of Lutherans in Bohemia. A combined Imperial-Catholic League army funded by Maximilian and led by Count Tilly pacified Upper and Lower Austria before invading Bohemia, where they defeated Christian of Anhalt at the White Mountain in November 1620. Although the battle was far from decisive, the rebels were demoralised by lack of pay, shortages of supplies, and disease, while the countryside had been devastated by Imperial troops. Frederick fled Bohemia and the revolt collapsed.[40]

The Palatinate Campaign

By abandoning Frederick, the German princes hoped to restrict the dispute to Bohemia, but Maximilian's dynastic ambitions made this impossible. In the October 1619 Treaty of Munich, Ferdinand agreed to transfer the Palatinate's electoral vote to Bavaria and allow him to annex the Upper Palatinate.[41] Many Protestants supported Ferdinand because they objected to deposing the legally elected king of Bohemia, and now opposed Frederick's removal on the same grounds. Doing so turned the conflict into a contest between Imperial authority and "German liberties", while Catholics saw an opportunity to regain lands lost since 1555. The combination destabilised large parts of the Empire.[42]

The strategic importance of the Palatinate and its proximity to the Spanish Road drew in external powers; in August 1620, the Spanish occupied the Lower Palatinate. James responded to this attack on his son-in-law by sending naval forces to threaten Spanish possessions in the Americas and the Mediterranean, and announced he would declare war if Spinola had not withdrawn his troops by spring 1621. These actions were greeted with approval by his domestic critics, who considered his pro-Spanish policy a betrayal of the Protestant cause.[43]

Spanish chief minister Olivares correctly interpreted this as an invitation to open negotiations, and in return for an Anglo-Spanish alliance offered to restore Frederick to his Rhineland possessions.[44] Since Frederick demanded full restitution of his lands and titles, which was incompatible with the Treaty of Munich, hopes of reaching a negotiated peace quickly evaporated. When the Eighty Years War restarted in April 1621, the Dutch provided Frederick military support to regain his lands, along with a mercenary army under Mansfeld paid for with English subsidies. Over the next eighteen months, Spanish and Catholic League forces won a series of victories; by November 1622, they controlled most of the Palatinate, apart from Frankenthal, held by a small English garrison under Sir Horace Vere. Frederick and the remnants of Mansfeld's army took refuge in the Dutch Republic.[45]

At a meeting of the Imperial Diet in February 1623, Ferdinand forced through provisions transferring Frederick's titles, lands, and electoral vote to Maximilian. He did so with support from the Catholic League, despite strong opposition from Protestant members, as well as the Spanish. The Palatinate was clearly lost; in March, James instructed Vere to surrender Frankenthal, while Tilly's victory over Christian of Brunswick at Stadtlohn in August completed military operations.[46] However, Spanish and Dutch involvement in the campaign was a significant step in internationalising the war, while Frederick's removal meant other Protestant princes began discussing armed resistance to preserve their own rights and territories.[47]

Danish intervention (1625–1629)

With Saxony dominating the Upper Saxon Circle and Brandenburg the Lower, both kreis had remained neutral during the campaigns in Bohemia and the Palatinate. After Frederick was deposed in 1623, John George of Saxony and the Calvinist George William of Brandenburg feared Ferdinand intended to reclaim former Catholic bishoprics currently held by Lutherans (see Map). This seemed confirmed when Tilly's Catholic League army occupied Halberstadt in early 1625.[48]

As Duke of Holstein, Christian IV was also a member of the Lower Saxon circle, while Denmark's economy relied on the Baltic trade and tolls from traffic through the Øresund.[49] In 1621, Hamburg accepted Danish 'supervision', while his son Frederick became joint-administrator of Lübeck, Bremen, and Verden; possession ensured Danish control of the Elbe and Weser rivers.[50]

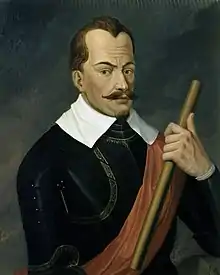

Ferdinand had paid Wallenstein for his support against Frederick with estates confiscated from the Bohemian rebels, and now contracted with him to conquer the north on a similar basis. In May 1625, the Lower Saxony kreis elected Christian their military commander, although not without resistance; Saxony and Brandenburg viewed Denmark and Sweden as competitors, and wanted to avoid either becoming involved in the Empire. Attempts to negotiate a peaceful solution failed as the conflict in Germany became part of the wider struggle between France and their Habsburg rivals in Spain and Austria.[51]

In the June 1624 Treaty of Compiègne, France subsidised the Dutch war against Spain for a minimum of three years, while in December 1625 the Dutch and English agreed to finance Danish intervention in the Empire. Hoping to create a wider coalition against Ferdinand, the Dutch invited France, Sweden, Savoy, and the Republic of Venice to join, but it was overtaken by events.[52] In early 1626, Cardinal Richelieu, main architect of the alliance, faced a new Huguenot rebellion at home and in the March Treaty of Monzón, France withdrew from Northern Italy, re-opening the Spanish Road.[53]

The Danish campaign plan involved three armies; the main force under Christian IV was to advance down the Weser, while Mansfeld attacked Wallenstein in Magdeburg and Christian of Brunswick linked up with the Calvinist Maurice of Hesse-Kassel. The advance quickly fell apart; Mansfeld was defeated at Dessau Bridge in April, and when Maurice refused to support him, Christian of Brunswick fell back on Wolfenbüttel, where he died of disease shortly after. The Danes were comprehensively beaten at Lutter in August, and Mansfeld's army dissolved following his death in November.[54]

Many of Christian's German allies, such as Hesse-Kassel and Saxony, had little interest in replacing Imperial domination for Danish, while few of the subsidies agreed in the Treaty of the Hague were ever paid. Charles I of England allowed Christian to recruit up to 9,000 Scottish mercenaries, but they took time to arrive, and while able to slow Wallenstein's advance, were insufficient to stop him.[55] By the end of 1627, Wallenstein occupied Mecklenburg, Pomerania, and Jutland, and began making plans to construct a fleet capable of challenging Danish control of the Baltic. He was supported by Spain, for whom it provided an opportunity to open another front against the Dutch.[56]

In May 1628, his deputy von Arnim besieged Stralsund, the only port with large enough shipbuilding facilities, but this brought Sweden into the war. Gustavus Adolphus despatched several thousand Scots and Swedish troops under Alexander Leslie to Stralsund, who was appointed governor.[57] Von Arnim was forced to lift the siege on 4 August, but three weeks later, Christian suffered another defeat at Wolgast. He began negotiations with Wallenstein, who despite his recent victories was concerned by the prospect of Swedish intervention, and thus anxious to make peace.[58]

With Austrian resources stretched by the outbreak of the War of the Mantuan Succession, Wallenstein persuaded Ferdinand to agree relatively lenient terms in the June 1629 Treaty of Lübeck. Christian retained his German possessions of Schleswig and Holstein, in return for relinquishing Bremen and Verden, and abandoning support for the German Protestants. While Denmark kept Schleswig and Holstein until 1864, this effectively ended its reign as the predominant Nordic state.[59]

Once again, the methods used to obtain victory explain why the war failed to end. Ferdinand paid Wallenstein by letting him confiscate estates, extort ransoms from towns, and allowing his men to plunder the lands they passed through, regardless of whether they belonged to allies or opponents. Anger at such tactics and his growing power came to a head in early 1628 when Ferdinand deposed the hereditary Duke of Mecklenburg, and appointed Wallenstein in his place. Although opposition to this act united all German princes regardless of religion, Maximilian of Bavaria was compromised by his acquisition of the Palatinate; while Protestants wanted Frederick restored and the position returned to that of 1618, the Catholic League argued only for pre-1627.[60]

Made over-confident by success, in March 1629 Ferdinand passed an Edict of Restitution, which required all lands taken from the Catholic church after 1555 to be returned. While technically legal, politically it was extremely unwise, since doing so would alter nearly every single state boundary in North and Central Germany, deny the existence of Calvinism and restore Catholicism in areas where it had not been a significant presence for nearly a century. Well aware none of the princes involved would agree, Ferdinand used the device of an Imperial edict, once again asserting his right to alter laws without consultation. This new assault on 'German liberties' ensured continuing opposition and undermined his previous success.[61]

Swedish intervention; 1630 to 1635

As ever, Richelieu's policy was to 'arrest the course of Spanish progress', and 'protect her neighbours from Spanish oppression'.[62] With French resources tied up in Italy, he helped negotiate the September 1629 Truce of Altmark between Sweden and Poland, freeing Gustavus Adolphus to enter the war. Partly a genuine desire to support his Protestant co-religionists, like Christian he also wanted to maximise his share of the Baltic trade that provided much of Sweden's income.[63]

With Swedish-occupied Stralsund providing a bridgehead, in June 1630 nearly 18,000 Swedish troops landed in the Duchy of Pomerania. Gustavus signed an alliance with Bogislaw XIV, Duke of Pomerania, securing his interests in Pomerania against the Catholic Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, another Baltic competitor linked to Ferdinand by family and religion.[64] The Smolensk War is considered a separate but related part of the Thirty Years' War.[65]

Expectations of widespread support proved unrealistic; by the end of 1630, the only new Swedish ally was Magdeburg, which was besieged by Tilly.[66] Despite the devastation inflicted on their territories by Imperial soldiers, both Saxony and Brandenburg had their own ambitions in Pomerania, which clashed with those of Gustavus; previous experience also showed inviting external powers into the Empire was easier than getting them to leave.[67]

However, once again Richelieu provided the requisite support; in the 1631 Treaty of Bärwalde, he provided funds for the Heilbronn League, a Swedish-led coalition of German Protestant states, including Saxony and Brandenburg.[68] Payments amounted to 400,000 Reichstaler, or one million livres per year, plus an additional 120,000 Reichstalers for 1630. While less than 2% of the total French state budget, it made up over 25% of the Swedish, and allowed Gustavus to support an army of 36,000.[69] He won major victories at Breitenfeld in September 1631, then Rain in April 1632, where Tilly was killed.[70]

After Tilly's death, Ferdinand turned once again to Wallenstein; knowing Gustavus was over extended, he marched into Franconia and established himself at Fürth, threatening the Swedish supply chain. In late August, Gustavus incurred heavy losses in an unsuccessful assault on the town, arguably the greatest blunder in his German campaign.[71] Two months later, the Swedes won a resounding victory at Lützen, where Gustavus was killed.[72] Rumours now began circulating Wallenstein was preparing to switch sides, and in February 1634, Ferdinand issued orders for his arrest; on 25th, he was assassinated by one of his officers in Cheb.[73]

Phase II; France joins the war 1635 to 1648

A serious Swedish defeat at Nördlingen in September 1634 threatened their participation, leading Richelieu to intervene directly. After tense negotiations with Swedish Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna, he agreed to provide additional subsidies in the April 1635 Treaty of Compiègne, and France declared war on Spain in May, beginning the 1635 to 1659 Franco-Spanish War. A few days later, Ferdinand agreed the Peace of Prague with the German states; he withdrew the Edict while the Heilbronn and Catholic Leagues were replaced by a single Imperial army, although Saxony and Bavaria retained control of their own forces. This is generally seen as the point when the conflict ceased to be primarily a German civil war.[74]

After invading the Spanish Netherlands in May 1635, the poorly equipped French army collapsed, suffering 17,000 casualties from disease and desertion. A Spanish offensive in 1636 reached Corbie in Northern France; although it caused panic in Paris, lack of supplies forced them to retreat, and it was not repeated.[75] In the March 1636 Treaty of Wismar, France formally joined the Thirty Years War in alliance with Sweden and hired an army led by Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar to support an offensive in the Rhineland. At the same time, the Swedes under Johan Banér marched into Brandenburg and re-established their position in North-East Germany with victory at Wittstock on 4 October 1636. [76]

Ferdinand II died in February 1637 and was succeeded by his son Ferdinand III, who faced a rapidly deteriorating military situation. Dutch leader Frederick Henry recaptured Breda in October, and three months later Bernhard destroyed an Imperial army at Rheinfelden. Although von Hatzfeldt defeated a Swedish-English-Palatine force at Vlotho in October 1638, the capture of Breisach by Bernhard in December secured French control of Alsace and severed the Spanish Road. Madrid was forced to resupply their armies in Flanders by sea, and in October 1639 the Dutch destroyed a large Spanish convoy at the Battle of the Downs.[77]

Pressure grew on Spanish minister Olivares to make peace, especially as attempts to obtain additional resources, such as hiring Polish auxiliaries, proved unsuccessful.[78] Dutch attacks on their possessions in Africa and the Americas caused increasing unrest in Portugal, then part of the Spanish Empire; combined with heavy taxes levied by Madrid, in 1640 it led to revolts in both Portugal and Catalonia.[79] In August 1640, the French captured Arras, then over-ran the rest of Artois; Olivares argued it was time to accept Dutch independence and prevent further losses in Flanders. Although the Empire remained a formidable power, it meant reducing Spanish support for Ferdinand, impacting his ability to continue the war.[80]

Despite the death of Bernhard, over the next two years the Franco-Swedish alliance won a series of battles in Germany, including Wolfenbüttel in June 1641 and Kempen in January 1642. At Second Breitenfeld in October 1642, Lennart Torstenson inflicted almost 10,000 casualties on an Imperial army led by Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria,[81] while success at Klingenthal in November left the Swedes firmly in control of Saxony.[82] Although Ferdinand realised military victory was no longer possible, he still hoped to exclude France and Sweden from peace talks and reach a settlement negotiated only with members of the Empire.[83]

The death of Richelieu in December was followed by that of Louis XIII on 14 May 1643, leaving the five-year-old Louis XIV as king. With France holding most of Alsace, Richelieu's successor Cardinal Mazarin re-focused on the war with Spain in the Netherlands. On 19 May, Condé won a famous victory over the Spanish at Rocroi, but it was less decisive than often assumed and the French could not take advantage.[84] One key factor was the devastation inflicted on the countryside by 25 years of warfare, which forced armies to spend more time foraging than fighting, and made it difficult to campaign away from their main supply lines.[85] The French also had to rebuild their army in Germany after it was shattered by an Imperial-Bavarian force led by Franz von Mercy at Tuttlingen in November.[86]

Three weeks after Rocroi, Ferdinand invited Sweden and France to attend peace negotiations in the Westphalian towns of Münster and Osnabrück, but talks were delayed when Christian of Denmark blockaded Hamburg and increased toll payments in the Baltic.[87] This severely impacted the Dutch and Swedish economies and in December 1643 the Swedes began the Torstenson War by invading Jutland, with the Dutch providing naval support. Hoping to regain Saxony, Ferdinand pulled together an Imperial army under Matthias Gallas to attack the Swedes from the rear, which proved a disastrous decision. Leaving Wrangel to finish the war in Denmark, in May 1644 Torstenson marched into the Empire; Gallas was unable to stop him, while the Danes sued for peace after their defeat at Fehmarn in October 1644.[88]

Ferdinand restarted peace talks in November, but his position continued to deteriorate; Gallas' army disintegrated and the remnants retreated into Bohemia, where they were scattered by Torstenson at Jankau in March 1645.[89] In May, a Bavarian force under von Mercy destroyed a French detachment at Herbsthausen, before he was defeated and killed at Second Nördlingen in August.[90] With Ferdinand unable to help, John George of Saxony signed a six-month truce with Sweden in September, followed by the March 1646 Treaty of Eulenberg in which he agreed to remain neutral until the end of the war.[91]

This allowed the Swedes, now led by Wrangel, to put pressure on the peace talks by devastating first Westphalia, then Bavaria; by the autumn of 1646, Maximilian was desperate to end the war he was largely responsible for starting. At this point, Olivares publicised secret discussions initiated by Mazarin in early 1646, in which he offered to exchange Catalonia for the Spanish Netherlands; angered by what they viewed as betrayal and concerned by French ambitions in Flanders, the Dutch agreed a truce with Spain in January 1647.[92] Seeking to release French troops and prevent further Swedish gains by neutralising Bavaria, Mazarin negotiated the Truce of Ulm, signed on 14 March 1647 by Bavaria, Cologne, France, and Sweden.[93]

%252C_ur_%22Theatri_Europ%C3%A6i...%22_1663_-_Skoklosters_slott_-_99875.tif.jpg.webp)

Turenne, French commander in the Rhineland, was ordered to attack the Spanish Netherlands but the plan fell apart when his mostly German troops mutinied, while the new Bavarian commander, Johann von Werth, declared his loyalty to the Emperor and refused to comply with the truce.[94] This forced Maximilian to do the same in September; he replaced Werth with von Bronckhorst-Gronsfeld, who linked up with an Imperial army under von Holzappel. Outnumbered by a Franco-Swedish army under Wrangel and Turenne, von Holzappel was defeated and killed at Zusmarshausen in May 1648; although Montecuccoli extracted most of his troops, all the baggage and artillery was captured, ending any offensive capability.[95]

While Turenne and Wrangel devastated Bavaria, a second Swedish force attacked Prague, seizing the castle and Malá Strana district in July. The main objective was to gain as much loot as possible before the war ended; they failed to take the Old Town but captured the Imperial library, along with treasures including the Codex Gigas, now in Stockholm. On 5 November, news arrived that Ferdinand had signed peace treaties with France and Sweden on 24 October, ending the war.[96]

The conflict outside Germany

Northern Italy

Northern Italy had been contested by France and the Habsburgs for centuries, since it was vital for control of South-West France, an area with a long history of opposition to the central authorities. While Spain remained the dominant power in Italy, its reliance on long exterior lines of communication was a potential weakness, especially the Spanish Road; this overland route allowed them to move recruits and supplies from Naples and Lombardy to their army in Flanders.[97]

French policy was to seek to disrupt this road wherever possible, either by attacking the Spanish-held Duchy of Milan, or by blocking the Alpine passes. The strategic importance of the Duchy of Mantua meant when the direct male line became extinct in December 1627, both powers became involved in the 1628 to 1631 War of the Mantuan Succession. The situation was complicated by Savoy, which saw an opportunity to gain territory; in March 1629, the French stormed Savoyard positions in the Pas de Suse, lifted the siege of Casale and captured the strategic fortress of Pinerolo.[98]

France and Savoy made peace in the April 1629 Treaty of Suza, which allowed French troops passage through Savoy, and recognised their control of Casale and Pinerolo. Possession of these fortresses gave France effective control of Piedmont, protected the Alpine passes into Southern France, and allowed them to threaten Milan at will.[99]

Between 1629 and 1631, plague exacerbated by troop movements killed 60,000 in Milan and 46,000 in Venice, with proportionate losses elsewhere.[100] Combined with the diversion of Imperial resources caused by Swedish intervention in 1630, this led to the Treaty of Cherasco in June 1631. The French candidate, Charles I Gonzaga, was confirmed as Duke of Mantua; although Richelieu's representative, Cardinal Mazarin, agreed to evacuate Pinerolo, it was later secretly returned under an agreement with Victor Amadeus I, Duke of Savoy. With the exception of the 1639 to 1642 Piedmontese Civil War, this secured the French position in Northern Italy for the next twenty years.[101]

Catalonia; Reapers' War

Throughout the 1630s, attempts to increase taxes to pay for the costs of the war in the Netherlands led to protests throughout Spanish territories; in 1640, these erupted into open revolts in Portugal and Catalonia, supported by Richelieu as part of his 'war by diversion'. Prompted by France, the rebels proclaimed the Catalan Republic in January 1641.[84] The Madrid government quickly assembled an army of 26,000 men to crush the revolt, and on 23 January, they defeated the Catalans at Martorell. The French now persuaded the Catalan Courts to recognise Louis XIII as Count of Barcelona, and ruler of the Principality of Catalonia.[80]

Three days later, a combined French-Catalan force defeated the Spanish at Montjuïc, a victory which secured Barcelona. However, the rebels soon found the new French administration differed little from the old, turning the war into a three-sided contest between the Franco-Catalan elite, the rural peasantry, and the Spanish. There was little serious fighting after France took control of Perpignan and Roussillon, establishing the modern Franco-Spanish border in the Pyrenees. In 1651, Spain recaptured Barcelona, ending the revolt.[102]

Outside Europe

In 1580, Philip II of Spain became ruler of the Portuguese Empire, and the 1602 to 1663 Dutch–Portuguese War began as an offshoot of the Dutch fight for independence from Spain. Even after union, the Portuguese dominated the Atlantic trade in Triangular trade, exporting slaves from West Africa and Angola to work sugar plantations in Brazil. In 1621, the Dutch West India Company was formed to challenge this control and captured the Brazilian port of Salvador in 1624. Although retaken in 1625, a second fleet established Dutch Brazil in 1630, which was then relinquished in 1654.[103]

This was accompanied by a struggle for control in the East Indies and Africa, increasing Portuguese resentment against the Spanish, who were perceived as prioritising their own colonies. In the end, the Portuguese retained control of Brazil and Angola, but the Dutch captured the Cape of Good Hope, as well as Portuguese possessions in Malacca, the Malabar Coast, the Moluccas and Ceylon.[104]

Peace of Westphalia (1648)

Preliminary discussions began in 1642 but only became serious in 1646; a total of 109 delegations attended at one time or other, with talks split between Münster and Osnabrück. The Swedes rejected a proposal that Christian of Denmark act as mediator, with Papal Legate Fabio Chigi and the Venetian Republic appointed instead. The Peace of Westphalia consisted of three separate agreements; the Peace of Münster between Spain and the Dutch Republic, the treaty of Osnabrück between the Empire and Sweden, plus the treaty of Münster between the Empire and France.[105]

The Peace of Münster was the first to be signed on 30 January 1648; it was part of the Westphalia settlement because the Dutch Republic was still technically part of the Spanish Netherlands and thus Imperial territory. The treaty confirmed Dutch independence, although the Imperial Diet did not formally accept that it was no longer part of the Empire until 1728.[106] The Dutch were also given a monopoly over trade conducted through the Scheldt estuary, confirming the commercial ascendancy of Amsterdam; Antwerp, capital of the Spanish Netherlands and previously the most important port in Northern Europe, would not recover until the late 19th century.[107]

Negotiations with France and Sweden were conducted in conjunction with the Imperial Diet, and were multi-sided discussions involving many of the German states. This resulted in the treaties of Münster and Osnabrück, making peace with France and Sweden respectively. Ferdinand resisted signing until the last possible moment, doing so on 24 October only after a crushing French victory over Spain at Lens, and with Swedish troops on the verge of taking Prague.[108]

Taken as a whole, the consequences of these two treaties can be divided into the internal political settlement and external territorial changes. Ferdinand accepted the supremacy of the Imperial Diet and legal institutions, reconfirmed the Augsburg settlement, and recognised Calvinism as a third religion. In addition, Christians residing in states where they were a minority, such as Catholics living under a Lutheran ruler, were guaranteed freedom of worship and equality before the law. Brandenburg-Prussia received Farther Pomerania, and the bishoprics of Magdeburg, Halberstadt, Kammin, and Minden. Frederick's son Charles Louis regained the Lower Palatinate and became the eighth Imperial elector, although Bavaria kept the Upper Palatinate and its electoral vote.[106]

Externally, the treaties formally acknowledged the independence of the Dutch Republic and the Swiss Confederacy, effectively autonomous since 1499. In Lorraine, the Three Bishoprics of Metz, Toul and Verdun, occupied by France since 1552, were formally ceded, as were the cities of the Décapole in Alsace, with the exception of Strasbourg and Mulhouse.[91] Sweden received an indemnity of five million thalers, the Imperial territories of Swedish Pomerania, and Prince-bishoprics of Bremen and Verden; this gave them a seat in the Imperial Diet.[109]

The Peace was later denounced by Pope Innocent X, who regarded the bishoprics ceded to France and Brandenburg as property of the Catholic church, and thus his to assign.[110] It also disappointed many exiles by accepting Catholicism as the dominant religion in Bohemia, Upper and Lower Austria, all of which were Protestant strongholds prior to 1618. Fighting did not end immediately, since demobilising over 200,000 soldiers was a complex business, and the last Swedish garrison did not leave Germany until 1654.[111]

The settlement failed to achieve its stated intention of achieving a 'universal peace'. Mazarin insisted on excluding the Burgundian Circle from the treaty of Münster, allowing France to continue its campaign against Spain in the Low Countries, a war that continued until the 1659 Treaty of the Pyrenees. The political disintegration of the Polish commonwealth led to the 1655 to 1660 Second Northern War with Sweden, which also involved Denmark, Russia and Brandenburg, while two Swedish attempts to impose its control on the port of Bremen failed in 1654 and 1666.[112]

It has been argued the Peace established the principle known as Westphalian sovereignty, the idea of non-interference in domestic affairs by outside powers, although this has since been challenged. The process, or 'Congress' model, was adopted for negotiations at Aix-la-Chapelle in 1668, Nijmegen in 1678, and Ryswick in 1697; unlike the 19th century 'Congress' system, these were to end wars, rather than prevent them, so references to the 'balance of power' can be misleading.[113]

Human and financial cost of the war

Historians often refer to the 'General Crisis' of the mid-17th century, a period of sustained conflict in states such as China, the British Isles, Tsarist Russia and the Holy Roman Empire. In all these areas, war, famine and disease inflicted severe losses on local populations.[114] While the Thirty Years War ranks as one of the worst of these events, precise numbers are disputed; 19th century nationalists often increased them to illustrate the dangers of a divided Germany.[115]

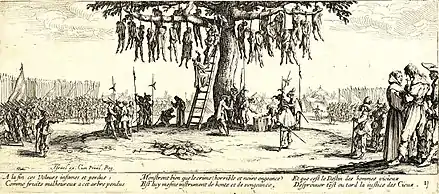

By modern standards, the number of soldiers involved was relatively low; most battles were fought between opposing forces of around 13,000 to 20,000, the largest being Alte Veste in 1632, which featured a combined total of 70,000 - 85,000.[116] However, the conflict has been described as one of the greatest medical catastrophes in history.[117] Well into the 19th century, far more soldiers died of disease than in battle; of an estimated 600,000 military casualties between 1618 and 1648, only 200,000 resulted from combat. Based on analysis of contemporary reports, less than 3% of civilian deaths derived from military action; the major causes were starvation (12%), bubonic plague (64%), typhus (4%), and dysentery (5%).[118]

Parish records show regular outbreaks of these diseases were common for decades prior to 1618, but the conflict greatly accelerated their spread. This was due to the influx of soldiers from foreign countries, the shifting locations of battle fronts, as well as the displacement of rural populations and migration into already crowded cities.[119] Poor harvests throughout the 1630s and repeated plundering of the same areas led to widespread famine; contemporaries record people eating grass, or too weak to accept alms, while instances of cannibalism were common.[120]

The modern consensus is the population of the Holy Roman Empire declined from 18-20 million in 1600 to 11–13 million in 1650, and did not recover to pre-war levels until 1750.[121] Nearly 50% of these losses appear to have been incurred during the first period of Swedish intervention from 1630 to 1635. The high mortality rate compared to the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in Britain may partly be due to the reliance of all sides on foreign mercenaries, often unpaid and required to live off the land. Lack of a sense of 'shared community' resulted in atrocities such as the destruction of Magdeburg, while creating large numbers of refugees, who were extremely susceptible to sickness and hunger. While flight may have saved lives in the short-term, in the long run it often proved catastrophic.[122]

In 1940, agrarian historian Günther Franz published Der Dreissigjährige Krieg und das Deutsche Volk, a detailed analysis of regional data from across Germany; membership of the Nazi Party meant his objectivity was challenged post-1945, but recent reviews support his general findings. He concluded "about 40% of the rural population fell victim to the war and epidemics; in the cities,...33%". There were wide regional variations; in the Duchy of Württemberg, the number of inhabitants fell by nearly 60%.[17] These figures can be misleading, since Franz calculated the absolute decline in pre and post-war populations, or 'total demographic loss'. It includes factors unrelated to death or disease, such as permanent migration to areas outside the Empire, or lower birthrates, a less obvious impact of extended warfare.[123]

Although it has been suggested some towns over-stated their losses to avoid taxes, individual records confirm serious declines; from 1620 to 1650, the population of Munich fell from 22,000 to 17,000, that of Augsburg from 48,000 to 21,000.[124] The financial impact is less clear; while the war caused short-term economic dislocation, overall it accelerated existing changes in trading patterns. It does not appear to have reversed ongoing macro-economic trends, such as the reduction of price differentials between regional markets, and a greater degree of market integration across Europe.[125] The death toll may have improved living standards for the survivors; one study shows wages in Germany increased by 40% in real terms between 1603 and 1652.[126]

Social impact

The breakdown of social order caused by the war was often more significant and longer lasting than the immediate damage.[127] The collapse of local government created landless peasants, who banded together to protect themselves from the soldiers of both sides, and led to widespread rebellions in Upper Austria, Bavaria and Brandenburg. Soldiers devastated one area before moving on, leaving large tracts of land empty of people and changing the eco-system. Food shortages were worsened by an explosion in the rodent population; Bavaria was over-run by wolves in the winter of 1638, its crops destroyed by packs of wild pigs the following spring.[128]

Contemporaries spoke of a 'frenzy of despair' as people sought to make sense of the turmoil and hardship unleashed by the war. Their attribution by some to supernatural causes led to a series of Witch-hunts, beginning in Franconia in 1626 and quickly spreading to other parts of Germany, which were often exploited for political purposes.[129] They originated in the Bishopric of Würzburg, an area with a history of such events going back to 1616 and now re-ignited by Bishop von Ehrenberg, a devout Catholic eager to assert the church's authority in his territories. By the time he died in 1631, over 900 people from all levels of society had been executed.[130]

At the same time, Prince-Bishop Johann von Dornheim held a similar series of large-scale witch trials in the nearby Bishopric of Bamberg. A specially designed Malefizhaus, or 'crime house', was erected containing a torture chamber, whose walls were adorned with Bible verses, where the accused were interrogated. These trials lasted five years and claimed over one thousand lives, including long-time Bürgermeister, or Mayor, Johannes Junius, and Dorothea Flock, second wife of Georg Heinrich Flock, whose first wife had also been executed for witchcraft in May 1628. During 1629, another 274 suspected witches were killed in the Bishopric of Eichstätt, plus another 50 in the adjacent Duchy of Palatinate-Neuburg.[131]

Elsewhere, persecution followed Imperial military success, expanding into Baden and the Palatinate following their reconquest by Tilly, then into the Rhineland.[132] Mainz and Trier also witnessed the mass killing of suspected witches, as did Cologne, where Ferdinand of Bavaria presided over a particularly infamous series of witchcraft trials, including that of Katharina Henot, who was executed in 1627.[133] In 2012, she and other victims were officially exonerated by the Cologne City Council.[134]

The extent to which these witch-hunts were symptomatic of the impact of the conflict on society is debatable, since many took place in areas relatively untouched by the war. Ferdinand and his advisors were concerned the brutality of the Würzburg and Bamberg trials would discredit the Counter-Reformation, and active persecution largely ended by 1630.[135] A scathing condemnation of the trials, Cautio Criminalis, was written by professor and poet Friedrich Spee, himself a Jesuit and former "witch confessor". This influential work was later credited with ending the practice in Germany, and eventually throughout Europe.[136]

Political consequences

The Peace reconfirmed "German liberties", ending Habsburg attempts to convert the Holy Roman Empire into an absolutist state similar to Spain. This allowed Bavaria, Brandenburg-Prussia, Saxony and others to pursue their own policies, while Sweden gained a permanent foothold in the Empire. Despite these setbacks, the Habsburg lands suffered less from the war than many others and became a far more coherent bloc with the absorption of Bohemia, and restoration of Catholicism throughout their territories.[137]

By laying the foundations of the modern nation state, Westphalia changed the relationship of subjects and their rulers. Previously, many had overlapping, sometimes conflicting political and religious allegiances; they were now understood to be subject first and foremost to the laws and edicts of their respective state authority, not to the claims of any other entity, be it religious or secular. This made it easier to levy national armies of significant size, loyal to their state and its leader; one lesson learned from Wallenstein and the Swedish invasion was the need for their own permanent armies, and Germany as a whole became a far more militarised society.[138]

The benefits of Westphalia for the Swedes proved short-lived. Unlike French gains which were incorporated into France, Swedish territories remained part of the Empire, and they became members of the Lower and Upper Saxon kreis. While this gave them seats in the Imperial Diet, it also brought them conflict with both Brandenburg-Prussia and Saxony, who were competitors in Pomerania. The income from their imperial possessions remained in Germany and did not benefit the kingdom of Sweden; although they retained Swedish Pomerania until 1815, much of it was ceded to Prussia in 1679 and 1720.[139]

Arguably, France gained more from the Thirty Years' War than any other power; by 1648, most of Richelieu's objectives had been achieved. They included separation of the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs, expansion of the French frontier into the Empire, and an end to Spanish military supremacy in Northern Europe.[140] Although the Franco-Spanish conflict continued until 1659 and Spain remained a global force for another two centuries, Westphalia allowed Louis XIV of France to complete the process of replacing her as the predominant European power.[141]

Although religion remained an issue throughout the 17th century, it was the last major war in Continental Europe in which it featured as the primary driver; later conflicts were either internal, such as the Camisards revolt in South-Western France, or relatively minor like the 1712 Toggenburg War.[142] The war created the outlines of a Europe that persisted until 1815 and beyond; the nation-state of France, the beginnings of a unified Germany and separate Austro-Hungarian bloc, a diminished but still significant Spain, independent smaller states like Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland, along with a Low Countries split between the Dutch Republic and what became Belgium in 1830.[139]

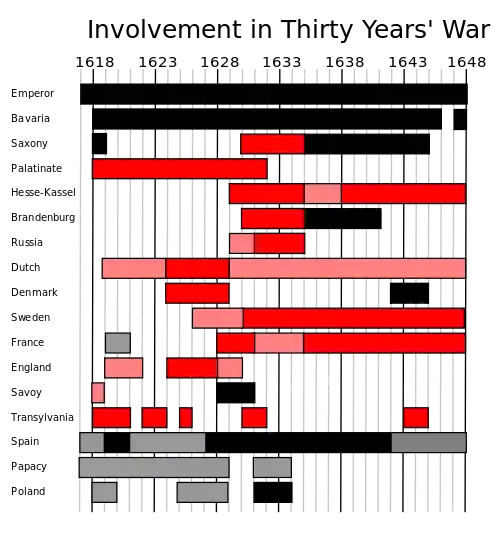

Involvement

| Directly against Emperor | |

| Indirectly against Emperor | |

| Directly for Emperor | |

| Indirectly for Emperor |

In fiction

Novels

- La vida y hechos de Estebanillo González, hombre de buen humor, compuesta por él mismo (Antwerp, 1646): The last of the great Spanish Golden Age picaresque novels, this is set against the background of the Thirty Years' War. It is thought to have been written by a man in the entourage of Ottavio Piccolomini. The main character crisscrosses Europe at war in his role as messenger; he witnesses the 1634 battle of Nordlingen, among other events.

- Simplicius Simplicissimus[143] (1668) by Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen, one of the most important German novels of the 17th century, is the comic fictional autobiography of a half-German, half-Scottish peasant turned mercenary. He serves under various powers during the war. The book is based on the author's first-hand experience.

- Memoirs of a Cavalier (1720) by Daniel Defoe is subtitled "A Military Journal of the Wars in Germany, and the Wars in England. From the Years 1632 to 1648".

- Alessandro Manzoni's The Betrothed (1842) is an historical novel taking place in Italy in 1629. It treats a couple whose marriage is interrupted by the bubonic plague, and other complications of Thirty Years' War.

- G. A. Henty, The Lion of the North: The Adventures of a Scottish Lad during the Thirty Years' War (2 vol., 1997 reprint). It is available under a number of subtitle variants, including a comic strip. Also Won By the Sword: A Story of the Thirty Years' War

- Gertrud von Le Fort's historical novel Die Magdeburgische Hochzeit is a fictional account of romantic and political intrigue during the siege of Magdeburg.

- Der Wehrwolf (1910) by Hermann Löns is a novel about an alliance of peasants using guerrilla tactics to fight the enemy during the Thirty Years' War.

- Alfred Döblin's sprawling historical novel Wallenstein (1920) is set during the Thirty Years' War; it explores the court of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand.

- The Last Valley[144] (1959), by John Pick, is about two men fleeing the Thirty Years' War.

- Das Treffen in Telgte (1979), by Günter Grass, is set in the aftermath of the war. He implicitly compared conditions to those in postwar Germany in the late 1940s.

- Michael Moorcock's novel, The War Hound and the World's Pain (1981), features a central character of Ulrich von Bek, a mercenary who took part in the sack of Magdeburg.

- Eric Flint's Ring of Fire series of alternative history novels, deals with a temporally displaced American town from the early 21st century that occupies territory in the early 1630s in war-torn Germany.

- Parts of Neal Stephenson's Baroque Cycle are set in lands devastated by the Thirty Years' War.

- In Die Henkerstochter (2008) by Oliver Pötzsch, the protagonist, hangman Jakob Kuisl, and other prominent characters have served in General Tilly's army and participated in the sacking of the city of Magdeburg during the Thirty Years' War. "The Great War" and Swedish incursion into north-central Germany are frequently referenced.

- Talbot Company[145] (2018) by Michael Regal is a story about a mercenary company set during the 30 Years' War. The eponymous company is hired to prevent a rogue Polish noble from restarting the Polish Swedish War, which Poland lost.

- Bruce Gardner's 2018 novel, Hope of Ages Past: An Epic Novel of Enduring Faith, Love, and the Thirty Years War, tells the story of the sack of Magdeburg and the Battle of Breitenfeld through the stories of a young Lutheran pastor and a peasant girl.

Theatre

- Friedrich Schiller's Wallenstein trilogy (1799) is a fictional account of the downfall of this general.

- Edmond Rostand's play Cyrano de Bergerac (1897) (act IV is set during the siege of Arras in 1640.)

- Bertolt Brecht's play Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder (1939), an antiwar piece, is set during the Thirty Years' War.

Film

- Queen Christina (1933), a film starring Greta Garbo, opens with the death of Christina's father, King Gustavus Adolphus, at the Battle of Lützen in the Thirty Years' War. The plot of the film is set against the backdrop of the war and Christina's determination as queen, depicted a decade later, to end the war and bring about peace.

- A Jester's Tale (1964) is a Czech film directed by Karel Zeman. Described by Zeman as a "pseudo-historical" film, it is an anti-war black comedy set during the Thirty Years' War.

- The Last Valley (1971) is a film starring Michael Caine and Omar Sharif, who discover a temporary haven from the Thirty Years' War. it was adapted from the novel The Last Valley.

Other

- Simplicius Simplicissimus (1934–1957) is an opera adaptation of the novel of the same name, with music by Karl Amadeus Hartmann.

- The Thirty Years' War is briefly referenced in the survival horror game Amnesia: The Dark Descent. The common enemies in the game are former soldiers of the war that abandoned their duty, died and became cursed to roam the woods they died in.

Gallery

War Scene

War Scene

by Sebastian Vrancx Battle of Sablat,

Battle of Sablat,

10 June 1619 Bautzen is besieged by Saxon troops, 1620 by Matthäus Merian

Bautzen is besieged by Saxon troops, 1620 by Matthäus Merian Battle of Wimpfen,

Battle of Wimpfen,

6 May 1622.jpg.webp) Battle of Fleurus,

Battle of Fleurus,

29 August 1622 Battle of Stadtlohn,

Battle of Stadtlohn,

6 August 1623 Siege of Stralsund,

Siege of Stralsund,

May to 4 August 1628 A cavalry battle

A cavalry battle

between 1626 and 1628

Battle of Frankfurt an der Oder,

Battle of Frankfurt an der Oder,

April 1631_-_Nationalmuseum_-_18031.tif.jpg.webp)

Notes

- States that fought against the Emperor at some point between 1618 to 1635

- Since officers were paid per soldier, numbers Reported frequently differed from Actual, ie those present and available for duty. Variances between Reported and Actual are estimated as averaging up to 25% for the Dutch, 35% for the French and 50% for the Spanish.[4] Most battles of the period were fought between opposing forces of 13,000 to 20,000 men; the numbers reflect Maximum at any one time and exclude citizen militia, who often formed a large proportion of garrisons

- All armies were multinational; an estimated 60,000 Scottish, English or Irish individuals fought on one side or the other during the period; based on an analysis of a mass grave discovered in 2011, fewer than 50% of "Swedish" forces at Lützen came from Scandinavia.[5]

- Maximum in Germany, excludes 24,000 home defence [6]

- Approved 80,000, actual 60,000 [9]

- 1640 figures for the Army of Flanders, when it was at its maximum strength; these are Reported numbers, so as mentioned elsewhere, Actual would have been considerably lower.[12]

- Parrott suggests many of these should be included in the figures for Imperial troops above, and that estimates of cavalry in particular were massively overstated [14]

References

- Croxton 2013, pp. 225–226.

- Heitz & Rischer 1995, p. 232.

- "into line with army of Gabriel Bethlen in 1620". Ágnes Várkonyi: Age of the Reforms, Magyar Könyvklub publisher, 1999. ISBN 963-547-070-3

- Parrott 2001, p. 8.

- Nicklisch et al. 2017.

- Schmidt & Richefort 2006, p. 49.

- "Victimario Histórico Militar".

- Parrott 2001, pp. 164-168.

- Van Nimwegen 2010, p. 62.

- "Gabriel Bethlen's army numbered 5,000 Hungarian pikemen and 1,000 German mercenary, with the anti-Habsburg Hungarian rebels numbered together approx. 35,000 men." László Markó: The Great Honors of the Hungarian State (A Magyar Állam Főméltóságai), Magyar Könyvklub 2000. ISBN 963-547-085-1

- Parrott 2001, p. 61.

- Parker 1972, p. 231.

- László Markó: The Great Honors of the Hungarian State (A Magyar Állam Főméltóságai), Magyar Könyvklub 2000. ISBN 963-547-085-1

- Parrott 2001, p. 62.

- Wilson 2009, p. 787.

- Wilson 2009, p. 4.

- Outram 2002, p. 248.

- Sutherland 1992, pp. 589–590.

- Parker 1984, pp. 17–18.

- Sutherland 1992, pp. 602–603.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 22–24.

- Wilson 2009, pp. 20–22.

- Wilson 1976, p. 259.

- Hayden 1973, pp. 1–23.

- Wilson 2009, p. 222.

- Wilson 2009, p. 224.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 47–49.

- Wilson 2008, p. 557.

- Wedgwood 1938, p. 50.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 63–65.

- Wilson 2009, pp. 271–274.

- Bassett 2015, p. 14.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 74–75.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 78–79.

- Bassett 2015, pp. 12,15.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 81–82.

- Wedgwood 1938, p. 94.

- Baramova 2014, pp. 121–122.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 98–99.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 127–129.

- Stutler 2014, pp. 37–38.

- Wedgwood 1938, p. 117.

- Zaller 1974, pp. 147–148.

- Zaller 1974, pp. 152–154.

- Spielvogel 2017, p. 447.

- Pursell 2003, pp. 182–185.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 162–164.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 179–181.

- Lockhart 2007, pp. 107–109.

- Murdoch 2000, p. 53.

- Wilson 2009, p. 387.

- Davenport 1917, p. 295.

- Wedgwood 1938, p. 208.

- Wedgwood 1938, p. 212.

- Murdoch & Grosjean 2014, pp. 43–44.

- Wilson 2009, p. 426.

- Murdoch & Grosjean 2014, pp. 48–49.

- Lockhart 2007, p. 170.

- Lockhart 2007, p. 172.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 232–233.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 242–244.

- Maland 1980, pp. 98–99.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 385–386.

- Norrhem 2019, pp. 28–29.

- Porshnev 1995, p. 106.

- Parker & Adams 1997, p. 120.

- O'Connell 1968, pp. 253–254.

- O'Connell 1968, p. 256.

- Porshnev & Dukes 1995, p. 38.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 305–306.

- Brzezinski 2001, p. 4.

- Brzezinski 2001, p. 74.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 220–222.

- Bireley 1976, p. 32.

- Israel 1995, pp. 272–273.

- Murdoch, Zickerman & Marks 2012, pp. 80–85.

- Bely 2014, pp. 94–95.

- Pazos 2011, pp. 130-131.

- Costa 2005, p. 4.

- Van Gelderen 2002, p. 284.

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 41.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 449-450.

- Milton, Axworthy & Simms 2018, pp. 60-65.

- Parker 1984, p. 153.

- Wilson 2009, p. 587.

- Wilson 2009, p. 643-645.

- Wilson 2009, pp. 482–484.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 472-473.

- Wilson 2009, pp. 693–695.

- Bonney 2002, p. 64.

- Wilson 2009, p. 711.

- Wedgwood 1938, p. 495.

- Wilson 2009, p. 716.

- Wedgwood 1938, p. 496.

- Wedgwood 1938, p. 499.

- Wedgwood 1938, p. 501.

- Hanlon 2016, pp. 118–119.

- Thion 2013, p. 62.

- Ferretti 2014, pp. 12–18.

- Kohn 1995, p. 200.

- Ferretti 2014, p. 20.

- Mitchell 2005, pp. 431–448.

- Van Groesen 2011, pp. 167–168.

- Gnanaprakasar 2003, pp. 153–172.

- Croxton 2013, pp. 3–4.

- Wilson 2009, p. 746.

- Israel 1995, pp. 197–199.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 500–501.

- Wilson 2009, p. 707.

- Ryan 1948, p. 597.

- Wedgwood 1938, p. 504.

- Wilson 2009, p. 757.

- Croxton 2013, pp. 331–332.

- Parker 2008, p. 1053.

- Wedgwood 1938, p. 510.

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 40.

- Outram 2001, p. 155.

- Outram 2001, pp. 159–161.

- Outram 2002, p. 250.

- Wilson 2009, p. 345.

- Parker 2008, p. 1058.

- Outram 2002, pp. 245–246.

- Outram 2001, p. 152.

- Wedgwood 1938, p. 512.

- Schulze & Volckart 2019, p. 30.

- Pfister, Riedel & Uebele 2012, p. 18.

- Wedgwood 1938, p. 516.

- Wilson 2009, p. 784.

- White 2012, p. 220.

- Jensen 2007, p. 93.

- Trevor-Roper 1967, pp. 83–117.

- Briggs 1996, p. 163.

- Briggs 1996, p. 172.

- Charter.

- Briggs 1996, pp. 171–172.

- Reilly 1959, pp. 51–55.

- McMurdie 2014, p. 65.

- Bonney 2002, pp. 89-90.

- McMurdie 2014, pp. 67–68.

- Lee 2001, pp. 67–68.

- Storrs 2006, pp. 6–7.

- "Lecture 6: Europe in the Age of Religious Wars, 1560–1715". historyguide.org. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- Grimmelshausen, H. J. Chr. (1669) [1668]. Der abentheurliche Simplicissimus [The adventurous Simplicissimus] (in German). Nuremberg: J. Fillion. OCLC 22567416.

- Pick, J.B. (1959). The Last Valley. Boston: Little, Brown (published 1960). OCLC 1449975.

- Regal, Michael (2018). Talbot Company: A Story of War and Suffering. Amazon. ISBN 9781726475532.

Sources

- Åberg, A. (1973). "The Swedish army from Lützen to Narva". In Roberts, M. (ed.). Sweden's Age of Greatness, 1632–1718. St. Martin's Press.

- Baramova, Maria (2014). Asbach, Olaf; Schröder, Peter (eds.). Non-splendid isolation: the Ottoman Empire and the Thirty Years War in The Ashgate Research Companion to the Thirty Years' War. Routledge. ISBN 978-1409406297.

- Bassett, Richard (2015). For God and Kaiser; the Imperial Austrian Army. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300178586.

- Bely, Lucien (2014). Asbach, Olaf; Schröder, Peter (eds.). France and the Thirty Years War in The Ashgate Research Companion to the Thirty Years' War. Ashgate. ISBN 978-1409406297.

- Benecke, Gerhard (1978). Germany in the Thirty Years War. St. Martin's Press.

- Bireley, Robert (1976). "The Peace of Prague (1635) and the Counterreformation in Germany". The Journal of Modern History. 48 (1): 31–69. doi:10.1086/241519.

- Bonney, Richard (2002). The Thirty Years War 1618-1648. Osprey Publishing.

- Briggs, Robin (1996). Witches & Neighbors: The Social And Cultural Context of European Witchcraft. Viking. ISBN 978-0670835898.

- Brzezinski, Richard (2001). Lützen 1632: Climax of the Thirty Years War: The Clash of Empires. Osprey. ISBN 978-1855325524.

- Charter (14 February 2012). "German 'witch' declared innocent after 385 years". The Australian. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- Clodfelter, M. (2008). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015 (2017 ed.). McFarland. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- Costa, Fernando Dores (2005). "Interpreting the Portuguese War of Restoration (1641-1668) in a European Context". Journal of Portuguese History. 3 (1).

- Cramer, Kevin (2007). The Thirty Years' War & German Memory in the Nineteenth Century. Lincoln: University of Nebraska. ISBN 978-0-8032-1562-7.

- Croxton, Derek (2013). The Last Christian Peace: The Congress of Westphalia as A Baroque Event. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137333322.

- Davenport, Frances Gardiner (1917). European Treaties Bearing on the History of the United States and Its Dependencies (2014 ed.). Literary Licensing. ISBN 978-1498144469.

- Dukes, Paul, ed. (1995). Muscovy and Sweden in the Thirty Years' War 1630–1635. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521451390.

- Ferretti, Giuliano (2014). "La politique italienne de la France et le duché de Savoie au temps de Richelieu". Dix-septième Siècle (in French). 1 (262): 7. doi:10.3917/dss.141.0007.

- German History (2018). "The Thirty Years War". German History. 36 (2): 252–270. doi:10.1093/gerhis/ghx121.

- Gindely, Antonín (1884). History of the Thirty Years' War. Putnam.

- Gnanaprakasar, Nalloor Swamy (2003). Critical History of Jaffna – The Tamil Era. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-8120616868.

- Grosjean, Alexia (2003). An Unofficial Alliance: Scotland and Sweden, 1569–1654. Leiden: Brill.

- Gutmann, Myron P. (1988). "The Origins of the Thirty Years' War". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 18 (4): 749–770. doi:10.2307/204823. JSTOR 204823.

- Hanlon, Gregory (2016). The Twilight Of A Military Tradition: Italian Aristocrats And European Conflicts, 1560-1800. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138158276.

- Hayden, J Michael (1973). "Continuity in the France of Henry IV and Louis XIII: French Foreign Policy, 1598-1615". The Journal of Modern History. 45 (1). JSTOR 1877591.

- Heitz, Gerhard; Rischer, Henning (1995). Geschichte in Daten. Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (in German). Koehler&Amelang. ISBN 3-7338-0195-4.

- Israel, Jonathan (1995). Spain in the Low Countries, (1635-1643) in Spain, Europe and the Atlantic: Essays in Honour of John H. Elliott. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521470452.

- Jensen, Gary F (2007). The Path of the Devil: Early Modern Witch Hunts. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742546974.

- Kamen, Henry (1968). "The Economic and Social Consequences of the Thirty Years' War". Past and Present. 39 (39): 44–61. doi:10.1093/past/39.1.44. JSTOR 649855.

- Kennedy, Paul (1988). The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000. New York: Harper Collins.

- Kohn, George (1995). Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: From Ancient Times to the Present. Facts on file. ISBN 978-0816027583.

- Langer, Herbert (1980). The Thirty Years' War (1990 ed.). Dorset Press. ISBN 978-0880292627.

- Lee, Stephen (2001). The Thirty Years War (Lancaster Pamphlets). Routledge. ISBN 978-0415268622.

- Lockhart, Paul D (2007). Denmark, 1513–1660: the rise and decline of a Renaissance monarchy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927121-4.

- Lynn, John A. (1999). The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714. Harlow, England: Longman.

- Maland, David (1980). Europe at War, 1600-50. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0333234464.

- McMurdie, Justin (2014). The Thirty Years' War: Examining the Origins and Effects of Corpus Christianum's Defining Conflict (PhD). George Fox University.

- Milton, Patrick; Axworthy, Michael; Simms, Brendan (2018). Towards The Peace Congress of Münster and Osnabrück (1643–1648) and the Westphalian Order (1648–1806) in "A Westphalia for the Middle East". C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-1787380233.

- Mitchell, Andrew Joseph (2005). Religion, revolt, and creation of regional identity in Catalonia, 1640-1643 (PHD). Ohio State University.

- Murdoch, Steve (2000). Britain, Denmark-Norway and the House of Stuart 1603–1660. Tuckwell. ISBN 978-1862321823.

- Murdoch, Steve (2001). Scotland and the Thirty Years' War, 1618–1648. Brill.

- Murdoch, S.; Zickerman, K; Marks, H (2012). "The Battle of Wittstock 1636: Conflicting Reports on a Swedish Victory in Germany". Northern Studies. 43.

- Murdoch, Steve; Grosjean, Alexia (2014). Alexander Leslie and the Scottish generals of the Thirty Years' War, 1618–1648. London: Pickering & Chatto.

- Nicklisch, Nicole; Ramsthaler, Frank; Meller, Harald; Others (2017). "The face of war: Trauma analysis of a mass grave from the Battle of Lützen (1632)". doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0178252. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Norrhem, Svante (2019). Mercenary Swedes; French subsidies to Sweden 1631–1796. Translated by Merton, Charlotte. Nordic Academic Press. ISBN 978-91-88661-82-1.

- O'Connell, Daniel Patrick (1968). Richelieu. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Outram, Quentin (2001). "The Socio-Economic Relations of Warfare and the Military Mortality Crises of the Thirty Years' War" (PDF). Medical History. 45 (2): 151–84. doi:10.1017/S0025727300067703. PMC 1044352. PMID 11373858.

- Outram, Quentin (2002). "The Demographic impact of early modern warfare". Social Science History. 26 (2): 245–272. doi:10.1215/01455532-26-2-245.

- Parker, Geoffrey (2008). "Crisis and catastrophe: The global crisis of the seventeenth century reconsidered". American Historical Review. 113 (4): 1053–1079. doi:10.1086/ahr.113.4.1053.

- Parker, Geoffrey; Adams, Simon (1997). The Thirty Years' War. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12883-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parker, Geoffrey (1984). The Thirty Years' War (1997 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0415128834.

- Parker, Geoffrey (1972). Army Flanders Spanish Road 2ed: The Logistics of Spanish Victory and Defeat in the Low Countries' Wars (2008 ed.). CUP. ISBN 978-0521543927.

- Parrott, David (2001). Richelieu's Army: War, Government and Society in France, 1624–1642. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521792097.

- Pazos, Conde Miguel (2011). "El tradado de Nápoles. El encierro del príncipe Juan Casimiro y la leva de Polacos de Medina de las Torres (1638–1642)". Studia Histórica, Historia Moderna (in Spanish). 33.

- Pfister, Ulrich; Riedel, Jana; Uebele, Martin (2012). "Real Wages and the Origins of Modern Economic Growth in Germany, 16th to 19th Centuries" (PDF). European Historical Economics Society. 17.

- Polišenský, J. V. (1954). "The Thirty Years' War". Past and Present. 6 (6): 31–43. doi:10.1093/past/6.1.31. JSTOR 649813.

- Polišenský, J. V. (1968). "The Thirty Years' War and the Crises and Revolutions of Seventeenth-Century Europe". Past and Present. 39 (39): 34–43. doi:10.1093/past/39.1.34. JSTOR 649854.

- Polisensky, Joseph (2001). "A Note on Scottish Soldiers in the Bohemian War, 1619–1622". In Murdoch, Steve (ed.). A Note on Scottish Soldiers in the Bohemian War, 1619–1622 in 'Scotland and the Thirty Years' war, 1618–1648'. Brill. ISBN 978-9004120860.

- Porshnev, Boris Fedorovich (1995). Dukes, Paul (ed.). Muscovy and Sweden in the Thirty Years' War, 1630-1635. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521451390.

- Prinzing, Friedrich (1916). Epidemics Resulting from Wars. Clarendon Press.

- Pursell, Brennan C. (2003). The Winter King: Frederick V of the Palatinate and the Coming of the Thirty Years' War. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0754634010.

- Rabb, Theodore K (1962). "The Effects of the Thirty Years' War on the German Economy". Journal of Modern History. 34 (1): 40–51. doi:10.1086/238995. JSTOR 1874817.

- Reilly, Pamela (1959). "Friedrich von Spee's Belief in Witchcraft: Some Deductions from the "Cautio Criminalis"". The Modern Language Review. 54 (1). doi:10.2307/3720833. JSTOR 3720833.

- Ringmar, Erik (1996). Identity, Interest and Action: A Cultural Explanation of the Swedish Intervention in the Thirty Years War (2008 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521026031.

- Roberts, Michael (1958). Gustavus Adolphus: A History of Sweden, 1611–1632. Longmans, Green and C°.

- Ryan, EA (1948). "Catholics and the Peace of Westphalia" (PDF). Theological Studies. 9 (4): 590–599. doi:10.1177/004056394800900407. S2CID 170555324. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- Schmidt, Burghart; Richefort, Isabelle (2006). "Les relations entre la France et les villes hanséatiques de Hambourg, Brême et Lübeck : Moyen Age-XIXe siècle". Direction des Archives, Ministère des affaires étrangères (in French).

- Schulze, Max-Stefan; Volckart, Oliver (2019). "The Long-term Impact of the Thirty Years War: What Grain Price Data Reveal" (PDF). Economic History.

- Spielvogel, Jackson (2017). Western Civilisation. Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 978-1305952317.

- Storrs, Christopher (2006). The Resilience of the Spanish Monarchy 1665–1700. OUP. ISBN 978-0199246373.

- Stutler, James Oliver (2014). Lords of War: Maximilian I of Bavaria and the Institutions of Lordship in the Catholic League Army, 1619-1626 (PDF) (PhD). Duke University.

- Sutherland, NM (1992). "The Origins of the Thirty Years War and the Structure of European Politics". The English Historical Review. CVII (CCCCXXIV). doi:10.1093/ehr/cvii.ccccxxiv.587.

- Theibault, John (1997). "The Demography of the Thirty Years War Re-revisited: Günther Franz and his Critics". German History. 15 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1093/gh/15.1.1.

- Thion, Stephane (2008). French Armies of the Thirty Years' War. Auzielle: Little Round Top Editions.

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh (1967). The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century: Religion, the Reformation and Social Change (2001 ed.). Liberty Fund. ISBN 978-0865972780.

- Van Gelderen, Martin (2002). Republicanism and Constitutionalism in Early Modern Europe: A Shared European Heritage Volume I. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521802031.

- Van Groesen, Michiel (2011). "Lessons Learned: The Second Dutch Conquest of Brazil and the Memory of the First". Colonial Latin American Review. 20 (2). doi:10.1080/10609164.2011.585770.

- Van Nimwegen, Olaf (2010). The Dutch Army and the Military Revolutions, 1588–1688. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843835752.

- Ward, A. W. (1902). The Cambridge Modern History. Volume 4: The Thirty Years War.

- Wedgwood, CV (1938). The Thirty Years War (2005 ed.). New York Review of Books. ISBN 978-1590171462.

- White, Matthew (2012). The Great Big Book of Horrible Things. W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0393081923.

- Wilson, Peter H. (2009). Europe's Tragedy: A History of the Thirty Years War. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9592-3.

- Wilson, Peter (2008). "The Causes of the Thirty Years War 1618-48". The English Historical Review. 123 (502). JSTOR 20108541.

- Zaller, Robert (1974). ""Interest of State": James I and the Palatinate". Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies. 6 (2): 144–175. doi:10.2307/4048141. JSTOR 4048141.

Further reading

- Helfferich, Tryntje, ed. The Thirty Years' War: A Documentary History, (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2009). 352 pages. 38 key documents including diplomatic correspondence, letters, broadsheets, treaties, poems, and trial records. excerpt and text search

- Sir Thomas Kellie, Pallas Armata or Military Instructions for the Learned, The First Part (Edinburgh, 1627).

- Monro, R. His Expedition with a worthy Scots Regiment called Mac-Keyes, (2 vols., London, 1637) www.exclassics.com/monro/monroint.htm.

- Dr Bernd Warlich has edited four diaries of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). These diaries can be viewed (in German) at: http://www.mdsz.thulb.uni-jena.de/sz/index.php

- Wilson, Peter H. ed. The Thirty Years' War: A Sourcebook (2010); includes state documents, treaties, correspondence, diaries, financial records, artwork; 240pp

External links