Thomas Hardy (political reformer)

Thomas Hardy (3 March 1752 – 11 October 1832) was a British shoemaker who was an early Radical, and the founder, first Secretary, and Treasurer of the London Corresponding Society.

Thomas Hardy | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Born | 3 March 1752 Larbert, Stirlingshire, Scotland |

| Died | 11 October 1832 (aged 80) London, England |

| Resting place | Bunhill Fields, London |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Master Shoemaker |

| Known for | Founding the London Corresponding Society. |

Early life

Thomas Hardy was born on 3 March 1752 in Larbert, Stirlingshire, Scotland, the son of a merchant seaman.[1] His father died in 1760 at sea while Thomas was still a boy. He was sent to school by his maternal grandfather[1] and later apprenticed to a shoemaker in Stirlingshire. He later worked in the Carron Iron Works. As a young man, arrived in London just before the American Revolutionary War. On 21 May 1781 he was married at St-Martin-in-the-Fields church to Lydia Priest, the youngest daughter of a carpenter and builder from Chesham, Buckinghamshire. The couple had six children, all of whom died in infancy. Lydia died in childbirth on 27 August 1794, her child (the sixth) being stillborn: the cause may have been the injuries she had sustained when a loyalist "Church and King" mob attacked the Hardy home some weeks earlier.[2] In 1791, Hardy opened his own boot and shoe shop at 9 Piccadilly, London.[1]

Involvement with the London Corresponding Society

Around 1792, Hardy founded the London Corresponding Society, starting out with just nine friends. However, they were soon joined by others, including Olaudah Equiano. Two years later, on 12 May 1794, it had grown so powerful that he was arrested by the King's Messenger, two Bow Street Runners, the private secretary to Home Secretary Dundas, and others on Crown charges of high treason.[3] It was during his imprisonment that Hardy's wife died, leaving him with an unfinished letter declaring her love for him.[4] The charges were prosecuted with Sir John Scott leading for the Crown, and William Garrow[1] among the prosecuting counsel; while Hardy was defended by Thomas Erskine. He was acquitted after nine days of testimony and debate, on Guy Fawkes Day, 1794.[1]

Death and legacy

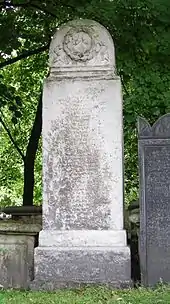

In later life Hardy ceased involvement in politics, and with the assistance of friends set up a small shoe shop in Tavistock Street, Covent Garden.[1] In September 1797 he moved to a smaller establishment in Fleet Street.[1] He died on 11 October 1832 at his home in Queen's Row, Pimlico, London.[1] He was buried at Bunhill Fields burial ground, where a granite obelisk, designed by John Woody Papworth, was later erected in his memory.[5]

See also

- Garrow's Law, BBC dramatisation based on Hardy's trial (episode 4, series 1)

References

- Emsley, Clive. "Hardy, Thomas (1752–1832)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- Uglow, Jenny (2014). In These Times: living in Britain through Napoleon's Wars, 1793–1815. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

- Thompson, E. P. (1963). The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Vintage Books. p. 20.

- Brown, P.A. (1965). The French Revolution in English History. Frank Cass & Co. Ltd. p. 123.

- Historic England. "Monument to Thomas Hardy, East Enclosure (1396521)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

Sources

- Thompson, E.P. (1963). The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Vintage Books.

- Hardy, Thomas (1832). Memoir of T. H., founder of ... the London Corresponding Society, for diffusing ... political knowledge among the people of Great Britain and Ireland, etc. Written by Himself. London.

- Angus, Ian (4 November 2009). "The Trial of Thomas Hardy: A Forgotten Chapter in the Working Class Fight for Democratic Rights". Socialist Voice: Marxist Perspectives for the 21st Century. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- Barker, George Fisher Russell (1890). . In Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney (eds.). Dictionary of National Biography. 24. London: Smith, Elder & Co.