Three levels of leadership model

The Three Levels of Leadership is a leadership model formulated in 2011 by James Scouller.[1] Designed as a practical tool for developing a person's leadership presence, knowhow and skill, it aims to summarize what leaders have to do, not only to bring leadership to their group or organization, but also to develop themselves technically and psychologically as leaders. It has been classified as an "integrated psychological" theory of leadership. It is sometimes known as the 3P model of leadership (the three Ps standing for Public, Private and Personal leadership).

The Three Levels of Leadership model attempts to combine the strengths of older leadership theories (i.e. traits, behavioral/styles, situational, functional) while addressing their limitations and, at the same time, offering a foundation for leaders wanting to apply the philosophies of servant leadership and "authentic leadership".[2]

Limitations of older leadership theories

In reviewing the older leadership theories, Scouller highlighted certain limitations in relation to the development of a leader's skill and effectiveness:[3]

- Trait theory: As Stogdill (1948)[4] and Buchanan & Huczynski (1997) had previously pointed out, this approach has failed to develop a universally agreed list of leadership qualities and "successful leaders seem to defy classification from the traits perspective".[5] Moreover, because traits theory gave rise to the idea that leaders are born not made, Scouller (2011) argued that its approach is better suited to selecting leaders than developing them.

- Behavioral styles theory: Blake and Mouton, in their managerial grid model, proposed five leadership styles based on two axes – concern for the task versus concern for people. They suggested that the ideal is the "team style", which balances concern for the task with concern for people. Scouller (2011) argued that this ideal approach may not suit all circumstances; for example, emergencies or turnarounds.

- Situational/contingency theories: Most of these (e.g. Hersey & Blanchard's situational leadership theory, House's path–goal theory, Tannenbaum & Schmidt's leadership continuum) assume that leaders can change their behavior at will to meet differing circumstances, when in practice many find it hard to do so even after training because of unconscious fixed beliefs, fears or ingrained habits. For this reason, leaders need to work on their underlying psychology if they are to attain the flexibility to apply these theories (Scouller, 2011).

- Functional theories: Widely used approaches like Kouzes & Posner's Five Leadership Practices model and Adair's Action-Centered Leadership theory assume that once the leader understands – and has been trained in – the required leadership behaviors, he or she will apply them as needed, regardless of their personality. However, as with the situational theories, Scouller noted that many cannot do so because of hidden beliefs and old habits so again he argued that most leaders may need to master their inner psychology if they are to adopt unfamiliar behaviors at will.

- Leadership presence: The best leaders usually have something beyond their behavior – something distinctive that commands attention, wins people's trust and enables them to lead successfully, which is often called "leadership presence" (Scouller, 2011). This is possibly why the traits approach became researchers' original line of investigation into the sources of a leader's effectiveness. However, that "something" – that presence – varies from person to person and research has shown it is hard to define in terms of common personality characteristics, so the traits approach failed to capture the elusive phenomenon of presence. The other leading leadership theories do not address the nature and development of presence.

How the three levels model addresses older theories' limitations

The section at the start of this page discussed the older theories' potential limitations. The table below explains how the Three Levels of Leadership model tries to address them.[6]

| Theory | Limitations | How three levels model addresses them |

|---|---|---|

| Traits |

|

|

| Behavioral/styles |

|

|

| Situational/contingency |

|

|

| Functional |

|

|

Levels

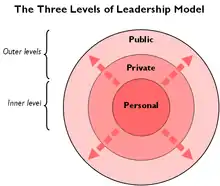

The three levels referred to in the model's name are Public, Private and Personal leadership. The model is usually presented in diagram form as three concentric circles and four outwardly directed arrows, with personal leadership in the center.

- The first two levels – public and private leadership – are "outer" or "behavioral" levels. Scouller distinguished between the behaviors involved in influencing two or more people simultaneously (what he called "public leadership") from the behavior needed to select and influence individuals one to one (which he called private leadership). He listed 34 distinct "public leadership" behaviors and a further 14 "private leadership" behaviors.

- The third level – personal leadership – is an "inner" level and concerns a person's leadership presence, knowhow, skills, beliefs, emotions and unconscious habits. "At its heart is the leader's self-awareness, his progress toward self-mastery and technical competence, and his sense of connection with those around him. It's the inner core, the source, of a leader's outer leadership effectiveness." (Scouller, 2011).

The idea is that if leaders want to be effective they must work on all three levels in parallel.

The two outer levels – public and private leadership – are what the leader must do behaviorally with individuals or groups to address the "four dimensions of leadership" (Scouller 2011). These are:

- A shared, motivating group purpose or vision.

- Action, progress and results.

- Collective unity or team spirit.

- Individual selection and motivation.

The inner level – personal leadership – refers to what leaders should do to grow their leadership presence, knowhow and skill. It has three aspects:

- Developing one's technical knowhow and skill.

- Cultivating the right attitude toward other people.

- Working on psychological self-mastery.

Scouller argued that self-mastery is the key to growing one's leadership presence, building trusting relationships with followers and enabling behavioral flexibility as circumstances change, while staying connected to one's core values (that is, while remaining authentic). To support leaders' development, he introduced a new model of the human psyche and outlined the principles and techniques of self-mastery (Scouller 2011).[7]

The assumption in this model is that personal leadership is the most powerful of the three levels. Scouller likened its effect to dropping a pebble in a pond and seeing the ripples spreading out from the center – hence the four arrows pointing outward in the diagram. "The pebble represents inner, personal leadership and the ripples the two outer levels. Helpful inner change and growth will affect outer leadership positively. Negative inner change will cause the opposite." (Scouller, 2011).

Public leadership

Public leadership refers to the actions or behaviors that leaders take to influence two or more people simultaneously – perhaps in a meeting or when addressing a large group. Public leadership is directed towards (1) setting and agreeing a motivating vision or future for the group or organization to ensure unity of purpose; (2) creating positive peer pressure towards shared, high performance standards and an atmosphere of trust and team spirit; and (3) driving successful collective action and results. Public leadership therefore serves the first three dimensions of leadership mentioned in the overview section.

There are 34 distinct public leadership behaviors (Scouller, 2011), which break out as follows:

- Setting the vision, staying focused:'briefing, challenging, navigating, and prioritising' 4 behaviors.

- Organizing, planning, giving power to others:'assigning and organising' 2 behaviors.

- Ideation, problem-solving, decision-making: 10 behaviors.

- Executing:'educating, energising, doing, measuring, following up, and tolerating' 6 behaviors.

- Group building and maintenance: 12 behaviors.

Leaders need to balance their time between the 22 vision/planning/thinking/execution behaviors and the 12 group building/maintenance behaviors.

According to the Three Levels of Leadership model, the key to widening one's repertoire of public leadership behaviors (and the skill with which they are performed) is attention to personal leadership.

Private leadership

Private leadership concerns the leader's one-to-one handling of individuals (which is the fourth of Scouller's four dimensions of leadership). Although leadership involves creating a sense of group unity, groups are composed of individuals and they vary in their ambitions, confidence, experience and psychological make-up. Therefore, they have to be treated as individuals – hence the importance of personal leadership. There are 14 private leadership behaviors (Scouller, 2011):

- Individual purpose and task (e.g. appraising, selecting, disciplining): 5 behaviors.

- Individual building and maintenance (e.g. recognizing rising talent): 9 behaviors.

Some people experience the powerful conversations demanded by private leadership (e.g. performance appraisals) as uncomfortable. Consequently, leaders may avoid some of the private leadership behaviors (Scouller, 2011), which reduces their leadership effectiveness. Scouller argued that the intimacy of private leadership leads to avoidance behavior either because of a lack of skill or because of negative self-image beliefs that give rise to powerful fears of what may happen in such encounters. This is why personal leadership is so important in improving a leader's one-to-one skill and reducing his or her interpersonal fears.

Personal leadership

Personal leadership addresses the leader's technical, psychological and moral development and its impact on his or her leadership presence, skill and behavior. It is, essentially, the key to making the theory of the two outer behavioral levels practical. Scouller went further in suggesting (in the preface of his book, The Three Levels of Leadership), that personal leadership is the answer to what Jim Collins called "the inner development of a person to level 5 leadership" in the book Good to Great – something that Collins admitted he was unable to explain.[8]

Personal leadership has three elements: (1) technical knowhow and skill; (2) the right attitude towards other people; and (3) psychological self-mastery.

The first element, Technical Knowhow and Skill, is about knowing one's technical weaknesses and taking action to update one's knowledge and skills. Scouller (2011) suggested that there are three areas of knowhow that all leaders should learn: time management, individual psychology and group psychology. He also described the six sets of skills that underlie the public and private leadership behaviors: (1) group problem-solving and planning; (2) group decision-making; (3) interpersonal ability, which has a strong overlap with emotional intelligence (4) managing group process; (5) assertiveness; (6) goal-setting.

The second element, Attitude Toward Others, is about developing the right attitude toward colleagues in order to maintain the leader's relationships throughout the group's journey to its shared vision or goal. The right attitude is to believe that other people are as important as oneself and see leadership as an act of service (Scouller, 2011). Although there is a moral aspect to this, there is also a practical side – for a leader's attitude and behavior toward others will largely influence how much they respect and trust that person and want to work with him or her. Scouller outlined the five parts of the right attitude toward others: (1) interdependence (2) appreciation (3) caring (4) service (5) balance. The two keys, he suggested, to developing these five aspects are to ensure that:

- There is a demanding, distinctive, shared vision that everyone in the group cares about and wants to achieve.

- The leader works on self-mastery to reduce self-esteem issues that make it hard to connect with, appreciate and adopt an attitude of service towards colleagues.

The third element of personal leadership is Self-Mastery. It emphasizes self-awareness and flexible command of one's mind, which allows the leader to let go of previously unconscious limiting beliefs and their associated defensive habits (like avoiding powerful conversations, e.g. appraisal discussions). It also enables leaders to connect more strongly with their values, let their leadership presence flow and act authentically in serving those they lead.

Because self-mastery is a psychological process, Scouller proposed a new model of the human psyche to support its practice. In addition, he outlined the principles of – and obstacles to – personal change and proposed six self-mastery techniques, which include mindfulness meditation.

Leadership presence

The importance and development of leadership presence is a central feature of the Three Levels of Leadership model. Scouller suggested that it takes more than the right knowhow, skills and behaviors to lead well – that it also demands "presence". Presence has been summed up in this way:

"What is presence? At its root, it is wholeness – the rare but attainable inner alignment of self-identity, purpose and feelings that eventually leads to freedom from fear. It reveals itself as the magnetic, radiating effect you have on others when you're being the authentic you, giving them your full respect and attention, speaking honestly and letting your unique character traits flow. As leaders, we must be technically competent to gain others' respect, but it's our unique genuine presence that inspires people and prompts them to trust us – in short, to want us as their leader." (Scouller, 2011.)[9]

In the Three Levels of Leadership model, "presence" is not the same as "charisma". Scouller argued that leaders can be charismatic by relying on a job title, fame, skillful acting or by the projection of an aura of "specialness" by followers – whereas presence is something deeper, more authentic, more fundamental and more powerful and does not depend on social status. He contrasted the mental and moral resilience of a person with real presence with the susceptibility to pressure and immoral actions of someone whose charisma rests only on acting skills (and the power their followers give them), not their true inner qualities.

Scouller also suggested that each person's authentic presence is unique and outlined seven qualities of presence: (1) personal power – command over one's thoughts, feelings and actions; (2) high, real self-esteem; (3) the drive to be more, to learn, to grow; (4) a balance of an energetic sense of purpose with a concern for the service of others and respect for their free will; (5) intuition; (6) being in the now; (7) inner peace of mind and a sense of fulfillment.[10]

Presence, according to this model, is developed by practicing personal leadership.

Link with authentic leadership and servant leadership

True leadership presence is, as Scouller defines it, synonymous with authenticity (being genuine and expressing one's highest values) and an attitude of service towards those being led. So in proposing self-mastery and cultivation of the right attitude toward others as a method of developing leadership presence, his model offers a "how to" counterpart to the ideas of "authentic leadership" and servant leadership.

Shared leadership

Most traditional theories of leadership explicitly or implicitly promote the idea of the leader as the admired hero – the person with all the answers that people want to follow. The Three Levels of Leadership model shifts away from this view. It does not reject the possibility of an impressive heroic leader, but it promotes the idea that this is only one way of leading (and, indeed, following) and that shared leadership is more realistic.

This view stems from Scouller's position that leadership is a process, "a series of choices and actions around defining and achieving a goal". Therefore, in his view, "leadership is a practical challenge that's bigger than the leader." He pointed out the danger of confusing "leadership" with the role of "leader". As other authors such as John Adair have pointed out, leadership does not have to rely on one person because anyone in a group can exert leadership. Scouller went further to suggest that "not only can others exert leadership; they must exert it at times if a group is to be successful." In other words, he believed that shared rather than solo leadership is not an idealistic aspiration; it is a matter of practicality. He suggested three reasons for this:[11]

- The sheer number of different behaviors required of leaders means they are unlikely to be equally proficient at all of them, so it is sensible for them to draw on their colleagues' strengths (that is, to allow them to lead at times).

- It is foolish to make one person responsible for all of the many leadership behaviors as it is likely to overburden them and frustrate any colleagues who are willing and able to lead – indeed, more able to lead – in certain circumstances.

- Shared leadership means that more people are involved in the group's big decisions and this promotes joint accountability which, as Katzenbach & Smith found in their research, is a distinct feature of high-performance teams.[12]

Now, potentially, this leaves the leader's role unclear – after all, if anyone in a group can lead, what is the distinct purpose of the leader? Scouller said this of the leader's role: "The purpose of a leader is to make sure there is leadership … to ensure that all four dimensions of leadership are [being addressed]." The four dimensions being: (1) a shared, motivating group purpose or vision (2) action, progress and results (3) collective unity or team spirit (4) attention to individuals. For example, the leader has to ensure that there is a motivating vision or goal, but that does not mean he or she has to supply the vision on their own. That is certainly one way of leading, but it is not the only way; another way is to co-create the vision with one's colleagues.

This means that the leader can delegate, or share, part of the responsibility for leadership. However, the final responsibility for making sure that all four dimensions are covered still rests with the leader. So although leaders can let someone else lead in a particular situation, they cannot let go of responsibility to make sure there is leadership; so when the situation changes the leader must decide whether to take charge personally or pass situational responsibility to someone else.

Criticism

One criticism of the Three Levels of Leadership model has been that it may be difficult for some leaders to use it as a guide to self-development without the assistance of a professional coach or psychotherapist at some point as many of its ideas around self-mastery are deeply psychological.[13]

See also

References

- Scouller, J. (2011). The Three Levels of Leadership: How to Develop Your Leadership Presence, Knowhow and Skill. Cirencester: Management Books 2000., ISBN 9781852526818

- "Businessballs information website: Leadership Theories Page, Integrated Psychological Approach section. At the end of the Integrated Psychological section it comments on the connection between the Three Levels model, authentic leadership and servant leadership". Businessballs.com. 2012-02-24. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- Scouller, J. (2011), pp. 34–35. Also see the "Businessballs information website: Integrated Psychological Leadership Models, Scouller's Integrated Approach section, "Analysis of Traditional Models of Leadership – Strengths and Weaknesses"". Businessballs.com. 2012-02-24. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- Stogdill, R.M. (1948). Personal Factors Associated with Leadership: a Survey of the Literature. Journal of Psychology, Vol. 25.

- Buchanan, D. & Huczynski, A. (1997). Organizational Behaviour (third edition), p.601. London: Prentice Hall.

- "Businessballs information website: Leadership Theories Page, Integrated Psychological Approach section – see "Scouller's 3P integration/extension of existing leadership models" table". Businessballs.com. 2012-02-24. Retrieved 2012-08-03.

- Scouller, J. (2011), pp. 137-237.

- Collins, J. (2001) pp. 37-38. Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap… and Others Don't. New York. HarperCollins. ISBN 0712676090

- Scouller, J. (2011), p.47.

- Scouller, J. (2011), pp. 67-75.

- Scouller, J. (2011), p.26.

- Katzenbach, J. & Smith, D. (1993). The Wisdom of Teams. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0875843670

- Rob MacLachlan (2011-08-30). "Review in People Management magazine by Rob MacLachlan, 30 August 2011". Peoplemanagement.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-08-03.