Tomb of Sampsigeramus

The Tomb of Sampsigeramus was a mausoleum that formerly stood in the necropolis of Emesa (modern-day Homs, Syria).[3][4] It is thought to have been built in 78 or 79 CE by a relative of the Emesene dynasty. The remains of the mausoleum were blown up with dynamite by the Ottoman authorities c. 1911, in order to make room for an oil depot.[3][4]

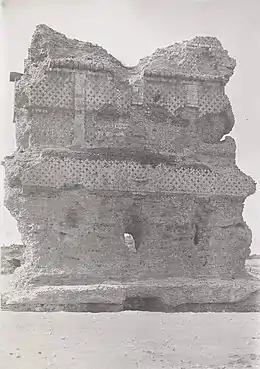

The Tomb of Sampsigeramus, photographed 1907, before its remains were blown up c. 1911 | |

| Location | Necropolis of Emesa (modern-day Homs), Syria |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°43′38.986″N 36°42′13.784″E[1] |

| Type | Mausoleum |

| History | |

| Builder | Gaius Julius Sampsigeramus |

| Founded | 78 or 79 CE[2] |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Ruined |

According to Andreas Kropp, the monument may be considered to have been a "hybrid creation" and a "fascinating one-off experiment" that resulted from "the cultural choices which the ruling class of Emesa had to face when attempting to reconcile Roman allegiance and Near Eastern tradition."[5]

Location

In the 18th century, Richard Pococke described the monument as standing "about a furlong to the west[6]" of what is now the Old City of Homs. The mausoleum was near the train station that exists now.[7] The greater part of the necropolis of Emesa was made to disappear by 1952 in order to build the municipal stadium known today as Khalid ibn al-Walid Stadium, after excavations begun in August 1936 had uncovered a total of 22 tombs.[8]

Owner

In the 16th century, Pierre Belon described a monument that was inscribed with the Greek letters of an epitaph of "Caius Cæſar[9]" – which may have made it a cenotaph of Caius Julius Caesar Vipsanianus.[10] It is however believed that Belon misread the inscription from this monument.[10] Pietro Della Valle found in the inscription a ΓΑΙΩ ΙΟΥΛΙΩ, but not "Caesar";[10] later Pococke, who made the first summary drawing of the mausoleum,[10] found that "on the eaſtern side the firſt word is ΓΑΙΟϹ[11]". Louis-François Cassas' reproduction of an inscription bearing the name "CAIUS CÆSAR" on plate 23 of Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, published 1799, is considered to have been a fantasy of the artist.[12] In the 19th century, William Henry Waddington copied a Greek inscription said to have belonged to the monument[13] and a copy of the latter by Dr. Skender Effendi (hereafter reproduced with the characters Ε, Ξ and Ω):

ΓΑΙΟϹΙΟΥΛΙΟϹ

ΦΑΒΙΑϹΑΜϹΙΓΕ

ΡΑΜΟϹΟΚΑΙϹΕΙΛ

ΑϹΓΑΙΟΥΙΟΥΛΙΟΥ

ΑΛΕΞΙΩΝΟϹΥΙΟϹ

ΖΩΝΕΠΟΙΗϹΕΝ

ΑΥΤΩΚΑΙΤΟΙϹΙΛ

ΟΙϹΕΤΟΥϹϞΤ[14]

Γάϊος Ἰούλιος, Φαβίᾳ, Σαμσιγέραμος ὁ καὶ Σεί[λ]ας, Γαΐου Ἰουλίου Ἀλεξίωνος υἱός, ζῶν ἐποίησεν [ἑ]αυτῷ καὶ τοῖς ἰ[δί]οις, ἔτους ϟτʹ[15]

Carlos Chad has given the following translation of the inscription reconstituted by Waddington: "Caius Julius Sampsigéram, de la tribu Fabia, dit Seilas, fils de Caius Julius Alexion, a construit de son vivant ce tombeau, pour lui-même et les siens, l'an 390 [of the Seleucids]", id est in 78 or 79 CE.[2]

The builder of the mausoleum may have been related to the Emesene dynasty[16] through Gaius Julius Alexion.[2] According to Maurice Sartre, the owner's Roman citizenship, attested by his tria nomina, strongly supports relatedness to the royal family.[17] The lack of allusion to royal kinship is best explained if the dynasty had been deprived of its kingdom shortly before the mausoleum was built and the said kingdom had been annexed to the Roman province of Syria, which occurred very likely between 72 and the construction of the mausoleum.[17][18] As worded by Kropp, "what the builder was really keen on stressing is that he was a Roman citizen bearing the tria nomina."[19]

Architecture

Upon completion, the monument was about 25 meters high and, as worded by Kropp, "retained the basic formal characteristics of a traditional nefesh, i.e. a pyramidal stele, albeit on an immense scale", comparable with those of Kamouh el Hermel (in Lebanon) and the Tomb of Hamrath at Suwayda (also destroyed).[21]

The outer walls and the roof were conceived in opus reticulatum, which is considered a rarity in the Orient,[10][22] following a purely Roman construction technique using concrete which certainly necessitated the intervention of workers of Italian origin or having undergone a specific training.[10] It was also unusual that opus reticulatum not be covered by stucco;[22] according to Kropp, Sampsigeramus may have ordered to leave it visible as a statement that he was "on good terms with the rulers of the world, that is the Roman people and in particular with the Roman emperor".[22]

Gallery

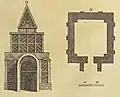

Pococke's "plan and view" of the monument[6] (A Description of the East, volume 2, plate 22, O & O), published 1745

Pococke's "plan and view" of the monument[6] (A Description of the East, volume 2, plate 22, O & O), published 1745 Drawing by Léon de Laborde lithographed and published 1837

Drawing by Léon de Laborde lithographed and published 1837.jpg.webp) Engraving published 1865 (direxit Lemaitre)

Engraving published 1865 (direxit Lemaitre)

See also

- Emesa helmet – which was found in the same necropolis

References

- Kropp 2013, p. 208 (map)

- Chad 1972, p. 92

- Seyrig 1952a, p. 204

- Kropp 2010, p. 204

- Kropp 2010, p. 214

- Pococke 1745, p. 141

- Seyrig 1952b, p. 106

- Seyrig 1952a, p. 205.

- Belon 1588, p. 346

- Nordiguian 2004, p. 127

- Pococke 1745, p. 142

- Nordiguian 2004, p. 127

- Jullien 1893

- Waddington 1870, p. 586

- Waddington 1870, p. 589

- Millar 1993, p. 84

- Sartre 2001

- Kropp 2010, p. 205

- Kropp 2010, pp. 205–206

- Schmidt-Colinet 1996, p. 373

- Kropp 2010, p. 206 & 212

- Kropp 2010, p. 207

Sources

- Belon, Pierre (1588). Les observations de plusieurs singularitez et choses mémorables (in French). Paris.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chad, Carlos (1972). Les Dynastes d'Émèse (in French).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kropp, Andreas (2010). "Earrings, Nefesh and Opus Reticulatum: Self-Representation of the Royal House of Emesa in the First Century AD". In Kaizer, Ted; Facella, Margherita (eds.). Kingdoms and Principalities in the Roman Near East. Franz Steiner Verlag Stuttgart.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kropp, Andreas J. M. (2013). Images and Monuments of Near Eastern Dynasts, 100 BC—AD 100. Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jullien, M. (1893). Sinaï et Syrie (in French). Lille.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Millar, Fergus (1993). The Roman Near East. Harvard University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nordiguian, Lévon, ed. (2004). Le voyage archéologique en Syrie et au Liban de Michel Jullien et Paul Soulerin en 1888 (in French). Presses de l'Université Saint-Joseph.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pococke, Richard (1745). A Description of the East. 2. London.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sartre, Maurice (2001). D'Alexandre à Zénobie : Histoire du Levant antique (in French). Fayard.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schmidt-Colinet, Andreas (1996). "Antike Denkmäler in Syrien. Die Stichvorlagen von Louis François Cassas (1756–1827) im Wallraf-Richartz-Museum in Köln". Kölner Jahrbuch (in German). 29.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Seyrig, Henri (1952a). "Antiquités Syriennes 53: Antiquités de la Nécropole d'Émèse (1re partie)". Syria. XXIX (3–4): 204–250. JSTOR 4390311.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (in French)

- Seyrig, Henri (1952b). "Le casque d'Emèse". Les Annales Archéologiques de Syrie. 2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waddington, W. H. (1870). Inscriptions grecques et latines de la Syrie (in French). Paris.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)