Toole's Theatre

Toole's Theatre, was a 19th-century West End building in William IV Street, near Charing Cross, in the City of Westminster. A succession of auditoria had occupied the site since 1832, serving a variety of functions, including religious and leisure activities. The theatre at its largest, after reconstruction in 1881–82, had a capacity of between 650 and 700.

1833 Lowther Rooms 1855 Polygraphic Hall 1869 Charing Cross Theatre 1876 Folly Theatre 1881 Toole's Theatre | |

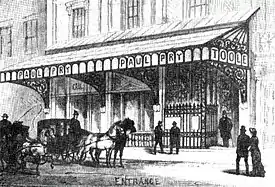

Façade of Toole's Theatre, 1882 | |

| |

| Address | William IV Street[n 1] Westminster, London |

|---|---|

| Designation | Demolished |

| Type | Playhouse |

| Capacity | 650–700[2] |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 1833 |

| Closed | 1895 |

| Rebuilt | 1869 Arthur Evers[3] 1876 Thomas Verity[4] 1882 J. J. Thompson[5] |

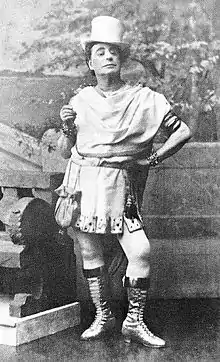

As the Charing Cross Theatre (1869–1876) the house became known for bills offering a mixture of drama, burlesque and operetta. Among the authors of its burlesques were W. S. Gilbert and H. B. Farnie. Its stars included Lydia Thompson, Lionel Brough and Willie Edouin. In 1876 Thompson and her husband, Alexander Henderson, became lessees of the theatre and renamed it the Folly Theatre. They continued the theatre's customary mix of operetta and burlesque. Their greatest successes were with English adaptations of French opéras bouffes and opéras comiques, most conspicuously Les cloches de Corneville, which began its record-breaking run (705 performances) at the Folly in 1878.

In 1879 the comic actor J. L. Toole took over the lease. In 1881 he changed the name to Toole's Theatre and had the building substantially reconstructed. He continued the policy of staging burlesques, but introduced more non-musical comedies and farces. Among the authors who wrote for the theatre were John Maddison Morton, F. C. Burnand and Henry Pottinger Stephens; composers included George Grossmith and Edward Solomon. The theatre was important for beginning the professional careers of many actors, writers and actor-managers. Among the playwrights whose early works were presented at Toole's were Arthur Wing Pinero and J. M. Barrie. Future stars who were members of the company as beginners included Kate Cutler, Florence Farr, Seymour Hicks, Irene and Violet Vanbrugh and Lewis Waller.

The lease of the theatre expired in 1895, and the lessor, the Charing Cross Hospital, did not renew it. The theatre was demolished in 1896.

History

Early years

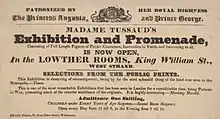

The building opened as the Lowther Rooms in 1833[6] following the redevelopment of the area by the Commissioners of Woods and Forests under Lord Lowther.[7][n 2] Its early attractions included an exhibition by Madame Tussaud in 1834, patronised by royalty,[9] but the venue rapidly acquired a certain notoriety:[10] a later commentator wrote that it became "a favourite place of resort with the young men of the period, who were attracted thither by a dismal form of entertainment known as 'Blake's Masquerades'".[3] After Blake departed, the building was used for religious purposes, first as the Roman Catholic Oratory of Saint Philip Neri from 1848 to 1852,[n 3] and then as a Protestant institute and working men's club under the presidency of Lord Shaftesbury.[3]

The premises were acquired by the entertainer William S. Woodin, who converted them, reopening as the Polygraphic Hall on 12 May 1855.[10] Woodin gave one-man comic shows, beginning with The Olio of Oddities.[12] He remained in possession of the hall for more than ten years, giving performances there between his provincial tours. When he was not in residence the hall was used for other one-man shows, lectures, amateur dramatic productions, and minstrel shows.[13]

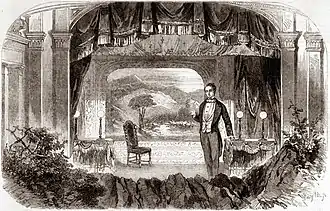

The building was sold to a partnership, E. W. Bradwell and W. R. Field, who acquired the adjoining houses and reconstructed the premises as a small playhouse called the Charing Cross Theatre.[13] The Times reported that they converted the building "into a regular playhouse, of light and elegant appearance, with two tiers of boxes, abundant stalls, a limited pit and no gallery – altogether an edifice satisfactorily answering to the favourite word 'bijou', and well worth seeing".[14] Its capacity was 600.[15] The theatre opened on 19 June 1869 with a triple bill consisting of an operetta, a three-act drama and a burlesque, the last being W. S. Gilbert's The Pretty Druidess, a parody of Bellini's opera Norma.[16]

In 1872 an American manager, John S. Clarke, became proprietor.[n 4] Under his management the theatre was variously advertised as the Charing Cross Theatre and the Theatre Royal, Charing Cross.[4] He renovated the interior, receiving praise from The Sunday Times:

Among Clarke's productions was a revival of Sheridan's The Rivals, featuring Mrs Stirling as Mrs Malaprop and Clarke as Bob Acres; it ran for more than 50 performances, an unheard-of run at the time for an old classic.[4]

In 1874 Lydia Thompson starred in H. B. Farnie's burlesque Blue Beard, in which she had played in the US nearly 500 times;[18] her co-stars were Lionel Brough and Willie Edouin.[18] The following year the theatre featured Kate Santley in a series of comic operas, and later Virginie Déjazet in a French season. John Hollingshead then presented burlesque, and in 1876 Thompson and her husband, Alexander Henderson (1828–1886) returned from a "farewell tour" of the US[n 5] and became proprietors of the theatre.[4]

Folly Theatre, 1876–1881

Henderson renamed the house the Folly Theatre. He said he meant to "shoot folly as it flies", and make the establishment the home of fun.[4][n 6] The premises were reconstructed and elaborately decorated under the supervision of Thomas Verity.[4] In his Dickens's Dictionary of London (1879), Charles Dickens Jr. described the Folly as "A little bandbox of a place, very prettily fitted up, and with a decided specialty for burlesque and opera bouffe".[22] It reopened on 16 October 1876, with a revival of Blue Beard.[4] At Christmas that year another Farnie burlesque was presented: Robinson Crusoe; it did well at the box-office, and Henderson continued to present opéra bouffe and burlesque. A triple bill of operettas by Hervé (Up the River), Lecocq (The Sea Nymphs) and Offenbach (The Creole) in 1877 featured Violet Cameron and Nelly Bromley, and was well received.[23] In 1878 the theatre had a tremendous success with Robert Planquette's Les cloches de Corneville, adapted by Farnie and Robert Reece, which (after transferring to the Globe Theatre and returning to the Folly) ran for 705 performances, setting a record that stood for nearly a decade.[4][24][n 7]

Thompson returned in Farnie and Reece's Stars and Garters in 1878, and continued with a series of burlesques including Tantalus; or, There's Many a Slip Twixt Cup and Lip and Carmen; or, Sold for a Song, until March 1879, when she and Henderson relinquished the management of the theatre.[26] It was then taken by the singer-manager Selina Dolaro; Offenbach's La Périchole was the highlight of her season.[4]

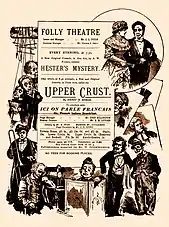

On 7 November 1879, the comic actor J. L. Toole took over the lease of the theatre. He opened with a triple bill of comedies: an early 19th-century "comedietta" called The Married Bachelor, H. J. Byron's three-act A Fool and His Money, and Ici on parle français, described by The Era as "the most successful farce of modern times", in which Toole played one of his most popular characters, Spriggins.[27] This was a financial success, and Toole followed it with Byron's comedy The Upper Crust, which remained in his repertoire for the rest of his career.[2] After presenting a revival of Dion Boucicault's Dickens adaption, Dot, based on The Cricket on the Hearth, and Hester's Mystery, an early play by Arthur Wing Pinero, as well as what the theatre historians Mander and Mitchenson describe as "some now forgotten pieces", Toole went on tour. In his absence R. C. Carton presented a summer season in 1881 that included Imprudence, Pinero's first three-act comedy.[2][28] When the season ended, Toole closed the theatre for substantial rebuilding; in December, while work was in progress, he announced a new name for the house: the Folly became Toole's Theatre,[29] the first in London to follow the common American practice of calling a theatre after its actor-manager or owner.[2]

Toole's Theatre, 1881–1896

Toole said that the rebuilding had cost him more than £10,000.[30] The capacity of the house was much enlarged:[30] Toole's held between 650 and 700 people.[2] The Morning Post observed that the building had "undergone so complete a process of renovation and embellishment that it may now be regarded as one of the handsomest theatres in the metropolis".[31] The Era praised the "spacious vestibule, the elegant foyer, the beautifully decorated staircases, the broad exits and entrances and the convenient verandah".[32] The paper also commented on the "startling metamorphosis" of the auditorium: "The consciousness that we were in an adapted lecture-room or Roman Catholic chapel has departed for ever, and we now behold a most commodious little theatre".[33] Toole did not emulate Richard D'Oyly Carte at the new Savoy Theatre by installing electric light:[34] the stage and front of house at Toole's remained gas-lit.[33]

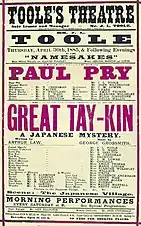

Toole had intended to open his reconstructed theatre with a new comedy by Byron, but the playwright's health prevented him from completing the work, and Toole opened, on 16 February 1882, with a triple bill of two revivals – Paul Pry, one of the greatest successes in his repertoire, and Mark Lemon's farce, Domestic Economy – and a new "comedietta", "Waiting Consent", by May Holt.[32][35]

Toole's staples were burlesque, light opera and comedies, including farces. Burlesques included Stage Dora; or, Who Killed Cock Robin, F. C. Burnand's parody of Sardou's Fédora (1883)[36] and Paw Claudian (1884) Burnand's lampoon of a recent costume drama Claudian by Henry Herman and W. G. Wills.[37] Comic operas included Mr. Guffin's Elopement[38] and The Great Tay-Kin,[39] both by Arthur Law and George Grossmith (1885), Billee Taylor by Henry Pottinger Stephens and Edward Solomon (1886),[40] and Lecocq's Pepita (1888, from his original La princesse des Canaries).[41]

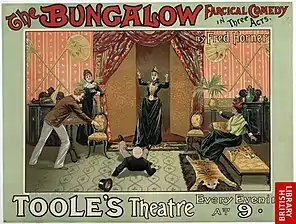

There were new comedies as well as old favourites. Among them were Pinero's Girls and Boys (1882),[43] John Maddison Morton's final play, a three-act farcical comedy called Going It (1885),[44] Herman Charles Merivale's The Butler (1886)[45] and The Don (1888),[46] and Fred Horner's The Bungalow (1890), an English version of Eugène Medina's La Garçonnière.[47] Ibsen's Ghost (1891), a one-act lampoon of Henrik Ibsen's plays and disciples, starring Irene Vanbrugh and Toole, was J. M. Barrie's first London play.[48] In 1892 Toole directed the premiere of Barrie's Walker, London, which ran for 497 performances.[49] In Toole's absence on tour other managements took temporary charge at his theatre, including William Terriss,[37] Willie Edouin[37] Augustin Daly with his New York company in 1884,[50] and Violet Melnotte in 1890.[51]

Toole retained a stock company, and many newcomers had their first opportunities at Toole's under his management, including Mary Brough,[50] Kate Cutler,[52] Florence Farr,[53] Seymour Hicks,[50] Eva Moore,[50] Irene Vanbrugh,[50] Violet Vanbrugh[54] and Lewis Waller.[55]

In 1895 the expiry of Toole's lease was approaching, and his health was in decline.[50] His last piece was Thoroughbred by Ralph Lumley, which opened on 13 February. Within a week, Toole had to withdraw. His role was temporarily taken by Rutland Barrington[56] until Toole recovered sufficiently to finish the run in September.[50] The last night under his management was on 28 September; Toole made his farewell to London audiences, and after touring until the following year he retired.[50] Two weeks after the closure, The Era reported:

No potential tenant willing to make the required outlay came forward, and a proposed plan for a redevelopment by the architect C. J. Phipps came to nothing.[58] The theatre's performance licence was withdrawn, and in the spring of 1896 the building was demolished. The hospital, which had for some time been expressing concern about the noise and the risk of fire from a theatre so close, used the site to build a new out-patients' department.[59]

Gallery

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- Known as "King William Street" when the building first opened.[1]

- The Lowther Rooms were opposite the popular Lowther Arcade, a covered market for fancy goods, some 250 feet long and considered at that time "one of the sights of London".[8]

- Here, in 1850, the Rev. (later Saint) J. H. Newman delivered his Lectures on Anglican Difficulties, after his conversion to Roman Catholicism.[11]

- Clarke was the brother-in-law of John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of the US president Abraham Lincoln, which Clarke said he hoped would not count against him in Britain.[4]

- It was billed as a farewell tour, but Thompson returned to the US several times over the next two decades.[19]

- Henderson had "Shoot folly as it flies" – a quotation from Alexander Pope[20] – printed at the top of the programmes for the theatre.[21]

- The record for the longest-running musical show was broken by Dorothy by Alfred Cellier and B. C. Stephenson, which ran for 931 performances from 1886 to 1889.[25]

- Back row: Mary Brough as Penny; Seymour Hicks as Andrew McPhail; Eliza Johnstone as Sarah Rigg; C. M. Lowne as Kit Upjohn.

Middle row: George Shelton as Ben; Mary Ansell as Nanny O'Brien; J. L. Toole as Jasper Phipps; Irene Vanbrugh as Bell Golightly; Effie Liston as Mrs Golightly.

Front: Cecil Ramsey as W.G.[42]

References

- "Public Amusements", The Morning Chronicle, 30 June 1834, p. 2

- Mander and Mitchenson, p. 228

- "Royal Charing Cross Theatre", The Morning Post, 21 June 1869, p. 2

- Mander and Mitchenson, p. 227

- Mander and Mitchenson, p. 233

- Classified advertisements, The Morning Post, 14 November 1833, p. 1; and The Standard, 14 November 1833, p. 1

- "The Improvements near Charing-Cross", The Gentleman's Magazine, March 1831, p. 206

- Thornbury, p. 132

- Classified advertisements, The Morning Post, 9 July 1834, p. 1

- Mander and Mitchenson, p. 222

- Thornbury, p. 129

- "Woodin's Olio of Oddities", The Morning Chronicle, 14 May 1855, p. 5

- Mander and Mitchenson, p. 224

- "Charing Cross Theatre", The Times, 24 June 1869, p. 6

- "Capacity of London Theatres", The Orchestra, 17 June 1870, p. 199

- Mander and Mitchenson, p. 225

- The Sunday Times, 5 January 1873, quoted in Mander and Mitchenson, p. 227

- "Charing-Cross Theatre", The Morning Post, 21 September 1874, p. 6

- Lawrence, W. J., and J. Gilliland. "Thompson, Lydia (1838–1908), dancer and actress", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 8 July 2020 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- "Alexander Pope", Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, edited by Knowles, Elizabeth, Oxford University Press, 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2020 (subscription required)

- "The Folly Theatre", Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 28 October 1876, p. 102

- Dickens, p. 103

- "Folly Theatre", The Era, 23 September 1877, p. 6

- Gänzl and Lamb, p. 356

- Gaye, pp. 1370, 1380 and 1525–1526

- "Folly Theatre", The Era, 2 March 1879, p. 5

- "The Theatres", The Pall Mall Gazette, 17 November 1879, p. 11

- Dawick, p. 404

- "Toole's", The Times, 27 December 1881, p. 6

- Toole, p. 274

- "Toole's Theatre", The Morning Post, 13 February 1882, p. 2

- "Opening of Toole's Theatre", The Era, 18 February 1882, p. 8

- "Toole's Theatre", The Era, 4 February 1882, p. 8

- "Savoy Theatre", The Times, 28 December 1881, p. 4

- "Toole's Theatre", The Standard, 17 February 1882, p. 3

- "The Theatre", Pall Mall Gazette, 28 May 1883, p 2

- "Toole's Theatre", The Morning Post, 19 June 1884, p. 3

- "Toole's Theatre", The Standard, 9 October 1882, p. 2

- "Toole's Theatre", The Daily News, 1 May 1885, p. 6

- "Toole's Theatre", The Morning Post, 2 August 1886, p. 6

- "Toole's Theatre", The Morning Post, 31 August 1888, p. 5

- "Studio photograph of the cast of Walker, London", Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 10 July 2020

- "Theatres", The Graphic, 4 November 1882, p. 10

- "Death of Mr Maddison Morton", The Era, 26 December 1891, p. 10

- "New Plays of the Month", The Era, 8 January 1887, p. 14

- "London Theatres", The Era, 10 March 1888, p. 14

- "The London Theatres", The Era, 12 October 1889, p. 14

- Jack, R. D. S. "Barrie, Sir James Matthew, baronet (1860–1937), playwright and novelist", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 9 July 2020 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Wearing, J. P. "The London West End Theatre in the 1890s", Educational Theatre Journal, October 1977, p. 320 (subscription required)

- Mander and Mitchenson, p. 230

- "Players of the Period", The Era, 30 March 1895, p. 9

- "Miss Kate Cutler", The Times, 18 May 1955, p. 13

- Hyde, Virginia Crosswhite. "Farr (married name Emery), Florence Beatrice (performing name Mary Lester) (1860–1917), author and mystic", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 9 July 2020 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Littlewood, S. R. "Vanbrugh, Violet (real name Violet Augusta Mary Barnes) (1867–1942), actress", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 9 July 2020 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Emeljanow, Victor. "Waller, Lewis (real name William Waller Lewis) (1860–1915), actor and theatre manager", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 9 July 2020 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- "Toole's Theatre", The Morning Post, 11 May 1895, p. 4

- "Theatrical Gossip", The Era, 12 October 1895, p. 10

- Mander and Mitchenson, pp. 230–231

- Mander and Mitchenson, p. 231

Sources

- Dawick, John (1993). Pinero: A Theatrical Life. Niwot: University of Colorado Press. ISBN 978-0-87081-302-3.

- Dickens, Charles, Jr. (1879). Dictionary of London: An Unconventional Handbook. London: C. Dickens & Evans. OCLC 914462893.

- Gänzl, Kurt; Andrew Lamb (1988). Gänzl's Book of the Musical Theatre. London: The Bodley Head. OCLC 966051934.

- Gaye, Freda (ed) (1967). Who's Who in the Theatre (fourteenth ed.). London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons. OCLC 5997224.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Mander, Raymond; Joe Mitchenson (1968). Lost Theatres of London. London: Rupert Hart-Davis. OCLC 41974.

- Thornbury, Walter (1887). Old and New London : A Narrative of its History, its People and its Places. London: Cassell. OCLC 1049974157.

- Toole, J. L. (1889). Joseph Hatton (ed.). Reminiscences of J. L. Toole, Volume 1. London: Hurst and Blackett. OCLC 876874718.