Trigona corvina

Trigona corvina (Cockerell, 1913) is a species of stingless bee that lives primarily in Central and South America.[1][2] In Panama, they are sometimes known as zagañas. They live in protective nests high in the trees, but they can be extremely aggressive and territorial over their resources.[1] They use their pheromones to protect their food sources and to signal their location to nest mates.[3] This black stingless bees of the tribe Meliponini can be parasitic toward citrus trees but also helpful for crop pollination.[2][4]

| Trigona corvina | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Apidae |

| Genus: | Trigona |

| Species: | T. corvina |

| Binomial name | |

| Trigona corvina Cockerell, 1913 | |

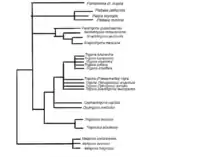

Taxonomy and phylogeny

Trigona corvina belong to Trigona, the largest genus of stingless bees, with over 80 species. T. corvina was once classified as a variety of Melipona ruficrus based on worker appearance.[2] Fossil records of the Meliponini tribe have been discovered and it is now understood that they differentiated from other related wasps in the Late Cretaceous period. The tribe is distinct with regards to their reduced wing venation and their reduced sting, which led to their development as stingless bees. It is possible that the differentiation of the Meliponini occurred in parallel with the dominance of flowering plants.[5]

Description and identification

Identification

Workers of T. corvina are primarily black with smokey wings; they have a thorax width of 2.34 mm.[2][6] The typical body length for a T. corvina is 6mm.[7] They have a wide facial quadrangle and five-toothed mandibles covered in reddish brown hairs. They also have black, erect hairs on their clypeus. The virgin queens are differentiated from the workers by their shiny head, wider thorax and longer wings. They are a larger insect overall than workers. Males have a narrower facial quadrangle than both the workers and the queen. They are also differentiated by their mandibles, which have red stripes at their base and also by their legs which are not uniformly black.[2] Trigona fuscipennis bees and Trigona corvina are often mistaken for one another since they are similar in appearance. Trigona fuscipennis workers are also completely black with one narrow red band just before the apex of the mandibles. But unlike the T. corvina species, they are smaller, have a slightly different mandible color and do not have erect black bristles.[8]

Nest structure

The nests of T. corvina are dark grey, ovoid nests build around small branches on trees in South America. Examples of their nests have weighed 69 pounds and are 22 inches high and 17-18 inches in diameter.[1] The brood area is always built first; it is strong and highly protective.[9] The brood encasement consists of pollen from emerged brood cells and pollen excrement from young adult bees.[9] Within the brood area, there are about 80,000 brood cells, all interconnected for easy passage. The queen cells are much larger and paler than the others. The next layers of the nest contain filled honey pots; these layers are also strongly supported with pollen excrement and wax.[1] The outer layers of the nest are designed to be easily broken in case of attack or a quick exit. The layers consist of sheaths of hardened and brittle resin or cerumen (wax) supported by columns. T. corvina are known for their uncleanliness, as most of the nest scutellum is built up on top of the nest.[2][9]

Thermal constraints

It has been demonstrated that body size and coloration impacts a bee’s ability to survive in certain temperatures. The larger and darker the bee, the better it does in colder environments. The color of the bee also influences where it tends to forage, either in sunlight or under the forest canopy. Trigona corvina is a midsized, black bee with a passive cooling rate of .32 °C/s. This is important because their foraging and nesting locations are often based on thermal constraints. For example, T. corvina refrain from foraging during the hottest period of the day. It also explains why they prefer foraging areas in shady areas.[6]

Heterozygosity

Trigona corvina have high heterozygosity due to their environment.[10] They typically live in regions with mosaic crops and plants that also have a low agricultural output. It has been demonstrated that drones have the highest diversity because they often come from many different colonies to mate with the Queen. It is important to maintain their heterozygosity for their continued proliferations and it is of concern because there has been a decline in diversity and abundance of insect pollinators.[10]

Distribution and habitat

T. corvina are native to Central and South America.[2][4] They were originally discovered in Guatemala, Costa Rica and the Canal Zone of Panama.[2] The species eventually spread to many more localities throughout Central and South America.[2] They build their nests in trees from 8 feet to 40 feet into the air and they usually prefer areas with plentiful plant life.[1] Since T. corvina are aggressive bees, their nests are regularly spaced to avoid unnecessary competition.[9] It has been shown that their colonies have a density of 1.0 colonies/ha.[11]

Colony cycle

A new colony is started when a virgin queen from one colony mates with a male of a neighboring colony.[12] They will then create a new colony close to the nest of the virgin queen.[12] New nests are created by the new queens but workers from the old nest must shuttle materials back and forth until the nest is complete. Additionally,many workers from the old nest must join the new queen in colonizing her nest until new generations of workers are born.[5] Nests can exist for over 20 years, showing the extreme longevity of colonies.[9] In a nest found in Panama, it was discovered that 91% of the bees in the nest were workers, 8% were males and <1% were virgin queens.[1] Since nests are built around exposed branches, T. corvina nests are often damaged or knocked down in the absence of natural causes, indicating attack by large animals.[13] Unfortunately for the bees, this results in colony loss.[13]

Behavior

Caste system

Trigona corvina colonies are founded by a single virgin queen who rapidly mates with a single male and her workers.[12] Once the queen begins her colony, she grows in size and eventually loses the ability to fly.[5] The queen lays all the eggs.[1] The worker bees do not reproduce and they have a 3:1 sister to brother relatedness ratio as do all members of Hymenoptera. Worker bees do the foraging, nest building, and raising of the brood. They are able to fly from colony to colony.[10]

Pheromones

T. corvina rely on pheromones for much of their communication with nest mates and rivals.[3] They produce pheromones from their labial glands.[14] The function of signaling depends on the profitability, but they commonly will scent mark a food source either for self-orientation, to deter rivals or to direct a nest mate to the resource. Once an individual finds a good food source, they will return to the same source for many days. If an individual detects the scent of a rival bee, they will avoid the plant in order to avoid conflict and to save time.[3] It has also been shown that pheromones are a method of sexual selection between male drones and queens.[14] This form of communication differentiates stingless bees from honey bees who use dances to indicate resource location.[15]

Local Enhancement

T. corvina have been shown to have local enhancement, which means that they prefer to land near other T. corvina individuals. They use both visual and epicuticular hydrocarbon cues to locate and monopolize food sources. Trigona corvina are able to recognize other members of their species through visual cues but they much prefer to use olfactory cues. This is because they can only see from 10–20 cm away but they are able to detect scent from 10–20 meters away. Color vision has emerged as an important characteristic for Trigona corvina since it enables them to identify other black bees from rival species.[7]

Foraging

It has been shown that a few members of the colony act as trained foraging bees. These trained bees will go on pilot flights to search out new food sources. When the trained bee returns, they will be visually conspicuous about the food location by repeated hovering and landing behavior. They will also deposit pheromone clouds around the location of the food in case they are not present to show the way. The presence of the trained bee is not necessary for the colony to find the food source, but it is helpful overall. As more and more members of the colony arrive at the food source, the trained bee becomes even less important.[7]

Interaction with other species

Diet

T. corvina have a minimum foraging range of 3.14 km and forage over 500 species of flowering plants, including over 100 tree species.[9] Due to their large foraging range, they have access to exotic and forest-edge species. They are quick pollinators and they have an average plant visitation time of 25.6 seconds/ 3 flowers. This quick foraging combined with their wide range allows them to visit a huge number of plants during each foraging expedition. From sampling pollen excrements, it is clear that Cavanillesia (Bombacaceae) is a primary food source for this species of bee.[9] Due to their aggressive nature, T. corvina are very territorial over their foraging areas and do not move without a fight.[16] Their aggression increases when there are more bees in a foraging area.[9]

Parasitism

Trigona corvina have been known to act as parasites to citrus plantations. They typically collect the sticky propolis from the surfaces of young orange leaves and then they collect the liquid that emerges from the leaf margins after they destroy them with their mandibles. They are so effective in their destruction of the citrus plants that they are able to prevent its growth.[2]

Defense

T. corvina are highly aggressive bees. Although this provides them a competitive advantage over less aggressive bees, it also results in fights to the death. They have four levels of aggression for different situations. Level 1 is a low intensity threat that may occur when a rival bee approaches an occupied food source. The bee will spread its mandibles and tilt its head up so that its mandibles are pointing at the rival. They will then lift their abdomen and hold their wings at a wide angle; level 1 is only a display of aggression. Level 2 involves brief bodily contact and the goal is to knock the intruder off of the plant or to the ground if the fight occurs in the air. Occasionally, the bees will nip at each other’s legs, but injury is not intended. Level 3 fighting involves biting with the intent of injury. They pull on each other’s mandibles and legs, often interlocking their mandibles. It is common for more than two bees to be involved. Level 4 aggressions frequently results in a fight to the death. Bees involved will release an alarm pheromone, which will bring nest mates to their assistance. Sometimes fighting can result in battles between entire colonies, if colonies are all T. corvina, it will usually result in a splitting of resources to avoid excessive deaths.[16]

There is a trade-off for Trigona corvina between effort spent defending their resource from intruders and foraging. They have to find an Evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS) between the two important activities in order to gain the most benefit. It has evolved that Trigona corvina foragers do best with interactions with other aggressive bees or with bees who are easily scared off.[9]

Competition

The African honey bee is a common competitor of T. corvina. When introduced to the same habitat, the T. corvina loses resources, since both forage in open spaces. Additionally, if a T. corvina nest is vacated, an African honey bee colony may move in. Honeybees can be very detrimental to T. corvina foraging because they are twice the size and are much more effective at collecting pollen. They also are able to forage more rapidly, so they have a much higher overall yield and their large size makes it difficult for the T. corvina to defend their territories.[9]

Parasites

T. corvina workers have been found with mites attached to the outer face of their hind tibiae. Males and queens are usually free of parasites.[2]

Role in agriculture

T. corvina, as a species of stingless bees, are important crop pollinators. Species native to Costa Rica are known to visit chayote flowers, which become much more fruitful when visited by T. corvina. They are also known to pollinate Panama hat plants (Carludovica palmata). In general, stingless bees are effective pollinators because they are less harmful to humans than honeybees, and they are resistant to the common diseases and parasites of honeybees.[4]

References

- Michener, Charles (September 1, 1946). "Notes on the Habits of Some Panamanian Stingless Bees (Hymenoptera, Apidæ)". Journal of the New York Entomological Society. 54 (3): 179–197. JSTOR 25005167.

- Schwarz, Herbert Ferlando; Bacon, Annette Louise (1948). Stingless bees (Meliponidae) of the Western Hemisphere : Lestrimelitta and the following subgenera of Trigona : Trigona, Paratrigona, Schwarziana, Parapartamona, Cephalotrigona, Oxytrigona, Scaura, and Mourella. hdl:2246/1231.

- Boogert, Neeltje Janna; Hofstede, Froucke Elisabeth; Monge, Ingrid Aguilar (2006). "The use of food source scent marks by the stingless bee Trigona corvina (Hymenoptera: Apidae): the importance of the depositor's identity". Apidologie. 37 (3): 366–375. doi:10.1051/apido:2006001.

- Heard, Tim A. (1999). "The role of stingless bees in crop pollination". Annual Review of Entomology. 44 (1): 183–206. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.44.1.183. PMID 15012371.

- Michener, Charles D. (2013-01-01). "The Meliponini". In Vit, Patricia; Pedro, Silvia R. M.; Roubik, David (eds.). Pot-Honey. Springer New York. pp. 3–17. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-4960-7_1. ISBN 978-1-4614-4959-1.

- Pereboom, J. J. M.; Biesmeijer, J. C. (2003). "Thermal constraints for stingless bee foragers: the importance of body size and coloration". Oecologia. 137 (1): 42–50. doi:10.1007/s00442-003-1324-2. PMID 12838404.

- Sommerlandt, Frank Max Joseph; Huber, Werner; Spaethe, Johannes (2014). "Social Information in the Stingless Bee, Trigona corvina Cockerell (Hymenoptera: Apidae): The Use of Visual and Olfactory Cues at the Food Site". Sociobiology. 61 (4). doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v61i4.401-406.

- Jarau, Stefan; Barth, Friedrich G (2008). "Stingless bees of the Golfo Dulce region, Costa Rica (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Apinae, Meliponini)". Kataloge der Oberösterreichischen Landesmuseen. 88: 267–276.

- Roubik, David W. (1981). "Comparative foraging behavior of Apis mellifera and Trigona corvina (Hymenoptera: Apidae) on Baltimora recta (Compositae)" (PDF). Revista de Biología Tropical. 29 (2): 177–183.

- Solórzano-Gordillo, E. de J.; Cabrera-Marín, N. V.; Mérida, J.; Vandame, R.; Sánchez, D. (2015). "Diversidad genética de dos especies de abejas sin aguijón, Trigona nigerrima (Cresson) y Trigona corvina (Cockerell) en paisajes cafetaleros del Sureste de México". Acta Zoológica Mexicana. 31 (1): 74–79. ISSN 0065-1737.

- Breed, Michael D.; McGlynn, Terrence P.; Sanctuary, Michael D.; Stocker, Erin M.; Cruz, Randolph (1999-11-01). "Distribution and abundance of colonies of selected meliponine species in a Costa Rican tropical wet forest". Journal of Tropical Ecology. 15 (6): 765–777. doi:10.1017/s0266467499001169. ISSN 1469-7831.

- John, L.; Aguilar, I.; Ayasse, M.; Jarau, S. (2012). "Nest-specific composition of the trail pheromone of the stingless bee Trigona corvina within populations". Insectes Sociaux. 59 (4): 527–532. doi:10.1007/s00040-012-0247-5.

- Slaa, E. J. (2006). "Population dynamics of a stingless bee community in the seasonal dry lowlands of Costa Rica". Insectes Sociaux. 53: 70–79. doi:10.1007/s00040-005-0837-6.

- Jarau, Stefan; Dambacher, Jochen; Twele, Robert; Aguilar, Ingrid; Francke, Wittko; Ayasse, Manfred (2010). "The Trail Pheromone of a Stingless Bee, Trigona corvina (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Meliponini), Varies between Populations". Chemical Senses Advance Access. 35 (7): 593–601. doi:10.1093/chemse/bjq057. PMID 20534775.

- "OpenStax CNX". cnx.org. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- Johnson, Leslie K.; Hubbell, Stephan P. (1974). "Aggression and Competition among Stingless Bees: Field Studies". Ecology. 55 (1): 120–127. doi:10.2307/1934624. JSTOR 1934624.