United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK or U.K.),[15] or Britain,[note 10] is a sovereign country in north-western Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland. The United Kingdom includes the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland, and many smaller islands within the British Isles.[16] Northern Ireland shares a land border with the Republic of Ireland. Otherwise, the United Kingdom is surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, with the North Sea to the east, the English Channel to the south and the Celtic Sea to the south-west, giving it the 12th-longest coastline in the world. The Irish Sea separates Great Britain and Ireland. The total area of the United Kingdom is 94,000 square miles (240,000 km2).

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland | |

|---|---|

| |

.svg.png.webp)  | |

| Capital and largest city | London 51°30′N 0°7′W |

| Official language and national language | English |

| Regional and minority languages[note 3] | |

| Ethnic groups (2011) | |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Constituent countries | |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Boris Johnson | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| House of Lords | |

| House of Commons | |

| Formation | |

| 1535 and 1542 | |

| 24 March 1603 | |

| 1 May 1707 | |

| 1 January 1801 | |

| 5 December 1922 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 242,495 km2 (93,628 sq mi)[8] (78th) |

• Water (%) | 1.51 (as of 2015)[9] |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | |

• 2011 census | 63,182,178[11] (22nd) |

• Density | 270.7/km2 (701.1/sq mi) (50th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2018) | medium · 33rd |

| HDI (2019) | very high · 13th |

| Currency | Pound sterling[note 5] (GBP) |

| Time zone | UTC (Greenwich Mean Time, WET) |

| UTC+1 (British Summer Time, WEST) | |

| [note 6] | |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy yyyy-mm-dd (AD) |

| Mains electricity | 230 V–50 Hz |

| Driving side | left[note 7] |

| Calling code | +44[note 8] |

| ISO 3166 code | GB |

| Internet TLD | .uk[note 9] |

The United Kingdom is a unitary parliamentary democracy and constitutional monarchy.[note 11][17][18] The monarch is Queen Elizabeth II, who has reigned since 1952.[19] The United Kingdom's capital is London, a global city and financial centre with an urban area population of 10.3 million.[20] The United Kingdom consists of four countries: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.[21] Their capitals are London, Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast, respectively. Apart from England, the countries have their own devolved governments,[22] each with varying powers.[23][24] Other major cities include Birmingham, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool, and Manchester.

The union between the Kingdom of England (which included Wales) and the Kingdom of Scotland in 1707 to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, followed by the union in 1801 of Great Britain with the Kingdom of Ireland created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Five-sixths of Ireland seceded from the UK in 1922, leaving the present formulation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The UK's name was adopted in 1927 to reflect the change.[note 12]

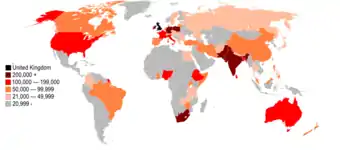

The nearby Isle of Man, Bailiwick of Guernsey and Bailiwick of Jersey are not part of the UK, being Crown dependencies with the British Government responsible for defence and international representation.[25] There are also 14 British Overseas Territories,[26] the last remnants of the British Empire which, at its height in the 1920s, encompassed almost a quarter of the world's landmass and was the largest empire in history. British influence can be observed in the language, culture and political systems of many of its former colonies.[27][28][29][30][31]

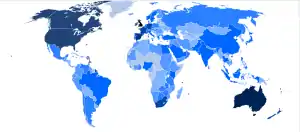

The United Kingdom has the world's fifth-largest economy by nominal gross domestic product (GDP), and the ninth-largest by purchasing power parity (PPP). It has a high-income economy and a very high human development index rating, ranking 15th in the world. It was the world's first industrialised country and the world's foremost power during the 19th and early 20th centuries.[32][33] The UK remains a great power, with considerable economic, cultural, military, scientific, technological and political influence internationally.[34][35] It is a recognised nuclear weapons state and is sixth in military expenditure in the world.[36] It has been a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council since its first session in 1946.

The United Kingdom is a member of the Commonwealth of Nations, the Council of Europe, the G7, the G20, NATO, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Interpol and the World Trade Organization (WTO). It was a member of the European Union (EU) and its predecessor, the European Economic Community (EEC), from 1 January 1973 until withdrawing on 31 January 2020.[37]

Etymology and terminology

The 1707 Acts of Union declared that the kingdoms of England and Scotland were "United into One Kingdom by the Name of Great Britain".[38][39][note 13] The term "United Kingdom" has occasionally been used as a description for the former kingdom of Great Britain, although its official name from 1707 to 1800 was simply "Great Britain".[40][41][42][43] The Acts of Union 1800 united the kingdom of Great Britain and the kingdom of Ireland in 1801, forming the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Following the partition of Ireland and the independence of the Irish Free State in 1922, which left Northern Ireland as the only part of the island of Ireland within the United Kingdom, the name was changed to the "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland".[44]

Although the United Kingdom is a sovereign country, England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are also widely referred to as countries.[45][46] The UK Prime Minister's website has used the phrase "countries within a country" to describe the United Kingdom.[21] Some statistical summaries, such as those for the twelve NUTS 1 regions of the United Kingdom refer to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland as "regions".[47][48] Northern Ireland is also referred to as a "province".[49][50] With regard to Northern Ireland, the descriptive name used "can be controversial, with the choice often revealing one's political preferences".[51]

The term "Great Britain" conventionally refers to the island of Great Britain, or politically to England, Scotland and Wales in combination.[52][53][54] It is sometimes used as a loose synonym for the United Kingdom as a whole.[55]

The term "Britain" is used both as a synonym for Great Britain,[56][57][58] and as a synonym for the United Kingdom.[59][58] Usage is mixed: the UK Government prefers to use the term "UK" rather than "Britain" or "British" on its own website (except when referring to embassies),[60] while acknowledging that both terms refer to the United Kingdom and that elsewhere '"British government" is used at least as frequently as "United Kingdom government".[61] The UK Permanent Committee on Geographical Names recognises "United Kingdom", "UK" and "U.K." as shortened and abbreviated geopolitical terms for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in its toponymic guidelines; it does not list "Britain" but notes 'it is only the one specific nominal term "Great Britain" which invariably excludes Northern Ireland.'[61] The BBC historically preferred to use "Britain" as shorthand only for Great Britain, though the present style guide does not take a position except that "Great Britain" excludes Northern Ireland.[62][63]

The adjective "British" is commonly used to refer to matters relating to the United Kingdom and is used in law to refer to United Kingdom citizenship and matters to do with nationality.[64] People of the United Kingdom use a number of different terms to describe their national identity and may identify themselves as being British, English, Scottish, Welsh, Northern Irish, or Irish;[65] or as having a combination of different national identities.[66][67] The official designation for a citizen of the United Kingdom is "British citizen".[61]

History

Prior to the Treaty of Union

Settlement by anatomically modern humans of what was to become the United Kingdom occurred in waves beginning by about 30,000 years ago.[68] By the end of the region's prehistoric period, the population is thought to have belonged, in the main, to a culture termed Insular Celtic, comprising Brittonic Britain and Gaelic Ireland.[69] The Roman conquest, beginning in 43 AD, and the 400-year rule of southern Britain, was followed by an invasion by Germanic Anglo-Saxon settlers, reducing the Brittonic area mainly to what was to become Wales, Cornwall and, until the latter stages of the Anglo-Saxon settlement, the Hen Ogledd (northern England and parts of southern Scotland).[70] Most of the region settled by the Anglo-Saxons became unified as the Kingdom of England in the 10th century.[71] Meanwhile, Gaelic-speakers in north-west Britain (with connections to the north-east of Ireland and traditionally supposed to have migrated from there in the 5th century)[72][73] united with the Picts to create the Kingdom of Scotland in the 9th century.[74]

In 1066, the Normans and their Breton allies invaded England from northern France. After conquering England, they seized large parts of Wales, conquered much of Ireland and were invited to settle in Scotland, bringing to each country feudalism on the Northern French model and Norman-French culture.[75] The Anglo-Norman ruling class greatly influenced, but eventually assimilated with, each of the local cultures.[76] Subsequent medieval English kings completed the conquest of Wales and made unsuccessful attempts to annex Scotland. Asserting its independence in the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath, Scotland maintained its independence thereafter, albeit in near-constant conflict with England.

The English monarchs, through inheritance of substantial territories in France and claims to the French crown, were also heavily involved in conflicts in France, most notably the Hundred Years War, while the Kings of Scots were in an alliance with the French during this period.[77] Early modern Britain saw religious conflict resulting from the Reformation and the introduction of Protestant state churches in each country.[78] Wales was fully incorporated into the Kingdom of England,[79] and Ireland was constituted as a kingdom in personal union with the English crown.[80] In what was to become Northern Ireland, the lands of the independent Catholic Gaelic nobility were confiscated and given to Protestant settlers from England and Scotland.[81]

In 1603, the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland were united in a personal union when James VI, King of Scots, inherited the crowns of England and Ireland and moved his court from Edinburgh to London; each country nevertheless remained a separate political entity and retained its separate political, legal, and religious institutions.[82][83]

In the mid-17th century, all three kingdoms were involved in a series of connected wars (including the English Civil War) which led to the temporary overthrow of the monarchy, with the execution of King Charles I, and the establishment of the short-lived unitary republic of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland.[84][85] During the 17th and 18th centuries, British sailors were involved in acts of piracy (privateering), attacking and stealing from ships off the coast of Europe and the Caribbean.[86]

Although the monarchy was restored, the Interregnum (along with the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the subsequent Bill of Rights 1689, and the Claim of Right Act 1689) ensured that, unlike much of the rest of Europe, royal absolutism would not prevail, and a professed Catholic could never accede to the throne. The British constitution would develop on the basis of constitutional monarchy and the parliamentary system.[87] With the founding of the Royal Society in 1660, science was greatly encouraged. During this period, particularly in England, the development of naval power and the interest in voyages of discovery led to the acquisition and settlement of overseas colonies, particularly in North America and the Caribbean.[88][89]

Though previous attempts at uniting the two kingdoms within Great Britain in 1606, 1667, and 1689 had proved unsuccessful, the attempt initiated in 1705 led to the Treaty of Union of 1706 being agreed and ratified by both parliaments.

Kingdom of Great Britain

On 1 May 1707, the Kingdom of Great Britain was formed, the result of Acts of Union being passed by the parliaments of England and Scotland to ratify the 1706 Treaty of Union and so unite the two kingdoms.[90][91][92]

In the 18th century, cabinet government developed under Robert Walpole, in practice the first prime minister (1721–1742). A series of Jacobite Uprisings sought to remove the Protestant House of Hanover from the British throne and restore the Catholic House of Stuart. The Jacobites were finally defeated at the Battle of Culloden in 1746, after which the Scottish Highlanders were brutally suppressed. The British colonies in North America that broke away from Britain in the American War of Independence became the United States of America, recognised by Britain in 1783. British imperial ambition turned towards Asia, particularly to India.[93]

Britain played a leading part in the Atlantic slave trade, mainly between 1662 and 1807 when British or British-colonial ships transported nearly 3.3 million slaves from Africa.[94] The slaves were taken to work on plantations in British possessions, principally in the Caribbean but also North America.[95] Slavery coupled with the Caribbean sugar industry had a significant role in strengthening and developing the British economy in the 18th century.[96] However, Parliament banned the trade in 1807, banned slavery in the British Empire in 1833, and Britain took a leading role in the movement to abolish slavery worldwide through the blockade of Africa and pressing other nations to end their trade with a series of treaties. The world's oldest international human rights organisation, Anti-Slavery International, was formed in London in 1839.[97][98][99]

From the union with Ireland to the end of the First World War

The term "United Kingdom" became official in 1801 when the parliaments of Great Britain and Ireland each passed an Act of Union, uniting the two kingdoms and creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.[100]

After the defeat of France at the end of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815), the United Kingdom emerged as the principal naval and imperial power of the 19th century (with London the largest city in the world from about 1830).[101] Unchallenged at sea, British dominance was later described as Pax Britannica ("British Peace"), a period of relative peace among the Great Powers (1815–1914) during which the British Empire became the global hegemon and adopted the role of global policeman.[102][103][104][105] By the time of the Great Exhibition of 1851, Britain was described as the "workshop of the world".[106] From 1853 to 1856, Britain took part in the Crimean War, allied with the Ottoman Empire in the fight against the Russian Empire,[107] participating in the naval battles of the Baltic Sea known as the Åland War in the Gulf of Bothnia and the Gulf of Finland, among others.[108] The British Empire was expanded to include India, large parts of Africa and many other territories throughout the world. Alongside the formal control it exerted over its own colonies, British dominance of much of world trade meant that it effectively controlled the economies of many regions, such as Asia and Latin America.[109][110] Domestically, political attitudes favoured free trade and laissez-faire policies and a gradual widening of the voting franchise. During the century, the population increased at a dramatic rate, accompanied by rapid urbanisation, causing significant social and economic stresses.[111] To seek new markets and sources of raw materials, the Conservative Party under Disraeli launched a period of imperialist expansion in Egypt, South Africa, and elsewhere. Canada, Australia, and New Zealand became self-governing dominions.[112] After the turn of the century, Britain's industrial dominance was challenged by Germany and the United States.[113] Social reform and home rule for Ireland were important domestic issues after 1900. The Labour Party emerged from an alliance of trade unions and small socialist groups in 1900, and suffragettes campaigned from before 1914 for women's right to vote.[114]

Britain fought alongside France, Russia and (after 1917) the United States, against Germany and its allies in the First World War (1914–1918).[115] British armed forces were engaged across much of the British Empire and in several regions of Europe, particularly on the Western front.[116] The high fatalities of trench warfare caused the loss of much of a generation of men, with lasting social effects in the nation and a great disruption in the social order.

After the war, Britain received the League of Nations mandate over a number of former German and Ottoman colonies. The British Empire reached its greatest extent, covering a fifth of the world's land surface and a quarter of its population.[117] Britain had suffered 2.5 million casualties and finished the war with a huge national debt.[116]

Interwar years and the Second World War

By the mid 1920s most of the British population could listen to BBC radio programmes.[118][119] Experimental television broadcasts began in 1929 and the first scheduled BBC Television Service commenced in 1936.[120]

The rise of Irish nationalism, and disputes within Ireland over the terms of Irish Home Rule, led eventually to the partition of the island in 1921.[121] The Irish Free State became independent, initially with Dominion status in 1922, and unambiguously independent in 1931. Northern Ireland remained part of the United Kingdom.[122] The 1928 Act widened suffrage by giving women electoral equality with men. A wave of strikes in the mid-1920s culminated in the General Strike of 1926. Britain had still not recovered from the effects of the war when the Great Depression (1929–1932) occurred. This led to considerable unemployment and hardship in the old industrial areas, as well as political and social unrest in the 1930s, with rising membership in communist and socialist parties. A coalition government was formed in 1931.[123]

Nonetheless, "Britain was a very wealthy country, formidable in arms, ruthless in pursuit of its interests and sitting at the heart of a global production system."[124] After Nazi Germany invaded Poland, Britain entered the Second World War by declaring war on Germany in 1939. Winston Churchill became prime minister and head of a coalition government in 1940. Despite the defeat of its European allies in the first year of the war, Britain and its Empire continued the fight alone against Germany. Churchill engaged industry, scientists, and engineers to advise and support the government and the military in the prosecution of the war effort.[124] In 1940, the Royal Air Force defeated the German Luftwaffe in a struggle for control of the skies in the Battle of Britain. Urban areas suffered heavy bombing during the Blitz. The Grand Alliance of Britain, the United States and the Soviet Union formed in 1941 leading the Allies against the Axis powers. There were eventual hard-fought victories in the Battle of the Atlantic, the North Africa campaign and the Italian campaign. British forces played an important role in the Normandy landings of 1944 and the liberation of Europe, achieved with its allies the United States, the Soviet Union and other Allied countries. The British Army led the Burma campaign against Japan and the British Pacific Fleet fought Japan at sea. British scientists contributed to the Manhattan Project which led to the surrender of Japan.

Postwar 20th century

During the Second World War, the UK was one of the Big Three powers (along with the U.S. and the Soviet Union) who met to plan the post-war world;[125][126] it was an original signatory to the Declaration by United Nations. After the war, the UK became one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council and worked closely with the United States to establish the IMF, World Bank and NATO.[127][128] The war left the UK severely weakened and financially dependent on the Marshall Plan,[129] but it was spared the total war that devastated eastern Europe.[130] In the immediate post-war years, the Labour government initiated a radical programme of reforms, which had a significant effect on British society in the following decades.[131] Major industries and public utilities were nationalised, a welfare state was established, and a comprehensive, publicly funded healthcare system, the National Health Service, was created.[132] The rise of nationalism in the colonies coincided with Britain's now much-diminished economic position, so that a policy of decolonisation was unavoidable. Independence was granted to India and Pakistan in 1947.[133] Over the next three decades, most colonies of the British Empire gained their independence, with all those that sought independence supported by the UK, during both the transition period and afterwards. Many became members of the Commonwealth of Nations.[134]

The UK was the third country to develop a nuclear weapons arsenal (with its first atomic bomb test in 1952), but the new post-war limits of Britain's international role were illustrated by the Suez Crisis of 1956. The international spread of the English language ensured the continuing international influence of its literature and culture.[135][136] As a result of a shortage of workers in the 1950s, the government encouraged immigration from Commonwealth countries. In the following decades, the UK became a more multi-ethnic society than before.[137] Despite rising living standards in the late 1950s and 1960s, the UK's economic performance was less successful than many of its main competitors such as France, West Germany and Japan.

.jpg.webp)

In the decades-long process of European integration, the UK was a founding member of the alliance called the Western European Union, established with the London and Paris Conferences in 1954. In 1960 the UK was one of the seven founding members of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), but in 1973 it left to join the European Communities (EC). When the EC became the European Union (EU) in 1992, the UK was one of the 12 founding members. The Treaty of Lisbon, signed in 2007, forms the constitutional basis of the European Union since then.

From the late 1960s, Northern Ireland suffered communal and paramilitary violence (sometimes affecting other parts of the UK) conventionally known as the Troubles. It is usually considered to have ended with the Belfast "Good Friday" Agreement of 1998.[140][141][142]

Following a period of widespread economic slowdown and industrial strife in the 1970s, the Conservative government of the 1980s under Margaret Thatcher initiated a radical policy of monetarism, deregulation, particularly of the financial sector (for example, the Big Bang in 1986) and labour markets, the sale of state-owned companies (privatisation), and the withdrawal of subsidies to others.[143] From 1984, the economy was helped by the inflow of substantial North Sea oil revenues.[144]

Around the end of the 20th century there were major changes to the governance of the UK with the establishment of devolved administrations for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.[145] The statutory incorporation followed acceptance of the European Convention on Human Rights. The UK is still a key global player diplomatically and militarily. It plays leading roles in the UN and NATO. Controversy surrounds some of Britain's overseas military deployments, particularly in Afghanistan and Iraq.[146]

21st century

The 2008 global financial crisis severely affected the UK economy. The coalition government of 2010 introduced austerity measures intended to tackle the substantial public deficits which resulted.[147] In 2014 the Scottish Government held a referendum on Scottish independence, with 55.3 per cent of voters rejecting the independence proposal and opting to remain within the United Kingdom.[148]

In 2016, 51.9 per cent of voters in the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union.[149] The UK remained a full member of the EU until 31 January 2020.[150]

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has seriously affected the UK. Emergency financial measures and controls on movement have been put in place, and plans made for a "bailout taskforce" so the government could "take emergency stakes in corporate casualties... in return for equity stakes".[151]

Geography

The total area of the United Kingdom is approximately 244,820 square kilometres (94,530 sq mi). The country occupies the major part of the British Isles[152] archipelago and includes the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern one-sixth of the island of Ireland and some smaller surrounding islands. It lies between the North Atlantic Ocean and the North Sea with the southeast coast coming within 22 miles (35 km) of the coast of northern France, from which it is separated by the English Channel.[153] In 1993 10 per cent of the UK was forested, 46 per cent used for pastures and 25 per cent cultivated for agriculture.[154] The Royal Greenwich Observatory in London was chosen as the defining point of the Prime Meridian[155] in Washington, D.C. in 1884, although due to more accurate modern measurement the meridian actually lies 100 metres to the east of the observatory.[156]

The United Kingdom lies between latitudes 49° and 61° N, and longitudes 9° W and 2° E. Northern Ireland shares a 224-mile (360 km) land boundary with the Republic of Ireland.[153] The coastline of Great Britain is 11,073 miles (17,820 km) long.[157] It is connected to continental Europe by the Channel Tunnel, which at 31 miles (50 km) (24 miles (38 km) underwater) is the longest underwater tunnel in the world.[158]

England accounts for just over half (53 per cent) of the total area of the UK, covering 130,395 square kilometres (50,350 sq mi).[159] Most of the country consists of lowland terrain,[154] with more upland and some mountainous terrain northwest of the Tees-Exe line; including the Lake District, the Pennines, Exmoor and Dartmoor. The main rivers and estuaries are the Thames, Severn and the Humber. England's highest mountain is Scafell Pike (978 metres (3,209 ft)) in the Lake District.

Scotland accounts for just under one-third (32 per cent) of the total area of the UK, covering 78,772 square kilometres (30,410 sq mi).[160] This includes nearly 800 islands,[161] predominantly west and north of the mainland; notably the Hebrides, Orkney Islands and Shetland Islands. Scotland is the most mountainous country in the UK and its topography is distinguished by the Highland Boundary Fault – a geological rock fracture – which traverses Scotland from Arran in the west to Stonehaven in the east.[162] The fault separates two distinctively different regions; namely the Highlands to the north and west and the Lowlands to the south and east. The more rugged Highland region contains the majority of Scotland's mountainous land, including Ben Nevis which at 1,345 metres (4,413 ft)[163] is the highest point in the British Isles.[164] Lowland areas – especially the narrow waist of land between the Firth of Clyde and the Firth of Forth known as the Central Belt – are flatter and home to most of the population including Glasgow, Scotland's largest city, and Edinburgh, its capital and political centre, although upland and mountainous terrain lies within the Southern Uplands.

Wales accounts for less than one-tenth (9 per cent) of the total area of the UK, covering 20,779 square kilometres (8,020 sq mi).[165] Wales is mostly mountainous, though South Wales is less mountainous than North and mid Wales. The main population and industrial areas are in South Wales, consisting of the coastal cities of Cardiff, Swansea and Newport, and the South Wales Valleys to their north. The highest mountains in Wales are in Snowdonia and include Snowdon (Welsh: Yr Wyddfa) which, at 1,085 metres (3,560 ft), is the highest peak in Wales.[154] Wales has over 2,704 kilometres (1,680 miles) of coastline.[157] Several islands lie off the Welsh mainland, the largest of which is Anglesey (Ynys Môn) in the north-west.

Northern Ireland, separated from Great Britain by the Irish Sea and North Channel, has an area of 14,160 square kilometres (5,470 sq mi) and is mostly hilly. It includes Lough Neagh which, at 388 square kilometres (150 sq mi), is the largest lake in the British Isles by area.[166] The highest peak in Northern Ireland is Slieve Donard in the Mourne Mountains at 852 metres (2,795 ft).[154]

The UK contains four terrestrial ecoregions: Celtic broadleaf forests, English Lowlands beech forests, North Atlantic moist mixed forests, and Caledon conifer forests.[167] The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 1.65/10, ranking it 161th globally out of 172 countries.[168]

Climate

Most of the United Kingdom has a temperate climate, with generally cool temperatures and plentiful rainfall all year round.[153] The temperature varies with the seasons seldom dropping below −20 °C (−4 °F) or rising above 35 °C (95 °F).[169][170] Some parts, away from the coast, of upland England, Wales, Northern Ireland and most of Scotland, experience a subpolar oceanic climate (Cfc). Higher elevations in Scotland experience a continental subarctic climate (Dfc) and the mountains experience a tundra climate (ET).[171] The prevailing wind is from the southwest and bears frequent spells of mild and wet weather from the Atlantic Ocean,[153] although the eastern parts are mostly sheltered from this wind since the majority of the rain falls over the western regions the eastern parts are therefore the driest. Atlantic currents, warmed by the Gulf Stream, bring mild winters;[172] especially in the west where winters are wet and even more so over high ground. Summers are warmest in the southeast of England and coolest in the north. Heavy snowfall can occur in winter and early spring on high ground, and occasionally settles to great depth away from the hills.

United Kingdom is ranked 4 out of 180 countries in the Environmental Performance Index.[173] A law has been passed that UK greenhouse gas emissions will be net zero by 2050.[174]

Administrative divisions

The geographical division of the United Kingdom into counties or shires began in England and Scotland in the early Middle Ages and was complete throughout Great Britain and Ireland by the early Modern Period.[175] Administrative arrangements were developed separately in each country of the United Kingdom, with origins which often predated the formation of the United Kingdom. Modern local government by elected councils, partly based on the ancient counties, was introduced separately: in England and Wales in a 1888 act, Scotland in a 1889 act and Ireland in a 1898 act, meaning there is no consistent system of administrative or geographic demarcation across the United Kingdom.[176] Until the 19th century there was little change to those arrangements, but there has since been a constant evolution of role and function.[177]

The organisation of local government in England is complex, with the distribution of functions varying according to local arrangements. The upper-tier subdivisions of England are the nine regions, now used primarily for statistical purposes.[178] One region, Greater London, has had a directly elected assembly and mayor since 2000 following popular support for the proposal in a referendum.[179] It was intended that other regions would also be given their own elected regional assemblies, but a proposed assembly in the North East region was rejected by a referendum in 2004.[180] Since 2011, ten combined authorities have been established in England. Eight of these have elected mayors, the first elections for which took place on 4 May 2017.[181] Below the regional tier, some parts of England have county councils and district councils and others have unitary authorities, while London consists of 32 London boroughs and the City of London. Councillors are elected by the first-past-the-post system in single-member wards or by the multi-member plurality system in multi-member wards.[182]

For local government purposes, Scotland is divided into 32 council areas, with wide variation in both size and population. The cities of Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen and Dundee are separate council areas, as is the Highland Council, which includes a third of Scotland's area but only just over 200,000 people. Local councils are made up of elected councillors, of whom there are 1,223;[183] they are paid a part-time salary. Elections are conducted by single transferable vote in multi-member wards that elect either three or four councillors. Each council elects a Provost, or Convenor, to chair meetings of the council and to act as a figurehead for the area.

Local government in Wales consists of 22 unitary authorities. These include the cities of Cardiff, Swansea and Newport, which are unitary authorities in their own right.[184] Elections are held every four years under the first-past-the-post system.[184]

Local government in Northern Ireland has since 1973 been organised into 26 district councils, each elected by single transferable vote. Their powers are limited to services such as collecting waste, controlling dogs and maintaining parks and cemeteries.[185] In 2008 the executive agreed on proposals to create 11 new councils and replace the present system.[186]

Dependencies

The United Kingdom has sovereignty over 17 territories which do not form part of the United Kingdom itself: 14 British Overseas Territories[26] and three Crown dependencies.[26][187]

The 14 British Overseas Territories are remnants of the British Empire: they are Anguilla; Bermuda; the British Antarctic Territory; the British Indian Ocean Territory; the British Virgin Islands; the Cayman Islands; the Falkland Islands; Gibraltar; Montserrat; Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha; the Turks and Caicos Islands; the Pitcairn Islands; South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands; and Akrotiri and Dhekelia on the island of Cyprus.[188] British claims in Antarctica have limited international recognition.[189] Collectively Britain's overseas territories encompass an approximate land area of 480,000 square nautical miles (640,000 sq mi; 1,600,000 km2),[190] with a total population of approximately 250,000.[191] The overseas territories also give the UK the worlds fifth largest Exclusive economic zone at 6,805,586 km2 (2,627,651 sq mi)[192]. A 1999 UK government white paper stated that: "[The] Overseas Territories are British for as long as they wish to remain British. Britain has willingly granted independence where it has been requested; and we will continue to do so where this is an option."[193] Self-determination is also enshrined in the constitutions of several overseas territories and three have specifically voted to remain under British sovereignty (Bermuda in 1995,[194] Gibraltar in 2002[195] and the Falkland Islands in 2013).[196]

The Crown dependencies are possessions of the Crown, as opposed to overseas territories of the UK.[197] They comprise three independently administered jurisdictions: the Channel Islands of Jersey and Guernsey in the English Channel, and the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea. By mutual agreement, the British Government manages the islands' foreign affairs and defence and the UK Parliament has the authority to legislate on their behalf. Internationally, they are regarded as "territories for which the United Kingdom is responsible".[198] The power to pass legislation affecting the islands ultimately rests with their own respective legislative assemblies, with the assent of the Crown (Privy Council or, in the case of the Isle of Man, in certain circumstances the Lieutenant-Governor).[199] Since 2005 each Crown dependency has had a Chief Minister as its head of government.[200]

%252C_administrative_divisions_-_Nmbrs_(multiple_zoom).svg.png.webp)

Politics

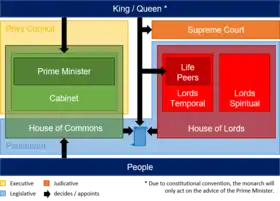

The United Kingdom is a unitary state under a constitutional monarchy. Queen Elizabeth II is the monarch and head of state of the UK, as well as 15 other independent countries. These 16 countries are sometimes referred to as "Commonwealth realms". The monarch has "the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, and the right to warn".[201] The Constitution of the United Kingdom is uncodified and consists mostly of a collection of disparate written sources, including statutes, judge-made case law and international treaties, together with constitutional conventions.[202] As there is no technical difference between ordinary statutes and "constitutional law", the UK Parliament can perform "constitutional reform" simply by passing Acts of Parliament, and thus has the political power to change or abolish almost any written or unwritten element of the constitution. No Parliament can pass laws that future Parliaments cannot change.[203]

Government

The UK has a parliamentary government based on the Westminster system that has been emulated around the world: a legacy of the British Empire. The parliament of the United Kingdom meets in the Palace of Westminster and has two houses: an elected House of Commons and an appointed House of Lords. All bills passed are given Royal Assent before becoming law.

The position of prime minister,[note 14] the UK's head of government,[204] belongs to the person most likely to command the confidence of the House of Commons; this individual is typically the leader of the political party or coalition of parties that holds the largest number of seats in that chamber. The prime minister chooses a cabinet and its members are formally appointed by the monarch to form Her Majesty's Government. By convention, the monarch respects the prime minister's decisions of government.[205]

The cabinet is traditionally drawn from members of the prime minister's party or coalition and mostly from the House of Commons but always from both legislative houses, the cabinet being responsible to both. Executive power is exercised by the prime minister and cabinet, all of whom are sworn into the Privy Council of the United Kingdom, and become Ministers of the Crown. The Prime Minister is Boris Johnson, who has been in office since 24 July 2019. Johnson is also the leader of the Conservative Party. For elections to the House of Commons, the UK is divided into 650 constituencies,[206] each electing a single member of parliament (MP) by simple plurality. General elections are called by the monarch when the prime minister so advises. Prior to the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011, the Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949 required that a new election must be called no later than five years after the previous general election.[207]

The Conservative Party, the Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats (formerly known as the Liberal Party) have, in modern times, been considered the UK's three major political parties,[208] representing the British traditions of conservatism, socialism and liberalism, respectively, though[209] the Scottish National Party has been the third-largest party by number of seats won, ahead of the Liberal Democrats, in all three elections that have taken place since the 2014 Scottish independence referendum. Most of the remaining seats were won by parties that contest elections only in one part of the UK: Plaid Cymru (Wales only); and the Democratic Unionist Party and Sinn Féin (Northern Ireland only).[note 15] In accordance with party policy, no elected Sinn Féin members of parliament have ever attended the House of Commons to speak on behalf of their constituents because of the requirement to take an oath of allegiance to the monarch.[210]

Devolved governments

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland each have their own government or executive, led by a First Minister (or, in the case of Northern Ireland, a diarchal First Minister and deputy First Minister), and a devolved unicameral legislature. England, the largest country of the United Kingdom, has no devolved executive or legislature and is administered and legislated for directly by the UK's government and parliament on all issues. This situation has given rise to the so-called West Lothian question, which concerns the fact that members of parliament from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland can vote, sometimes decisively,[211] on matters that affect only England.[212] The 2013 McKay Commission on this recommended that laws affecting only England should need support from a majority of English members of parliament.[213]

The Scottish Government and Parliament have wide-ranging powers over any matter that has not been specifically reserved to the UK Parliament, including education, healthcare, Scots law and local government.[214] In 2012, the UK and Scottish governments signed the Edinburgh Agreement setting out the terms for a referendum on Scottish independence in 2014, which was defeated 55.3 per cent to 44.7 per cent – resulting in Scotland remaining a devolved part of the United Kingdom.[215]

The Welsh Government and the Senedd (formerly the National Assembly for Wales)[216] have more limited powers than those devolved to Scotland.[217] The Senedd is able to legislate on any matter not specifically reserved to the UK Parliament through Acts of the Senedd.

The Northern Ireland Executive and Assembly have powers similar to those devolved to Scotland. The Executive is led by a diarchy representing unionist and nationalist members of the Assembly.[218] Devolution to Northern Ireland is contingent on participation by the Northern Ireland administration in the North-South Ministerial Council, where the Northern Ireland Executive cooperates and develops joint and shared policies with the Government of Ireland. The British and Irish governments co-operate on non-devolved matters affecting Northern Ireland through the British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference, which assumes the responsibilities of the Northern Ireland administration in the event of its non-operation.

The UK does not have a codified constitution and constitutional matters are not among the powers devolved to Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland. Under the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty, the UK Parliament could, in theory, therefore, abolish the Scottish Parliament, Senedd or Northern Ireland Assembly.[219][220] Indeed, in 1972, the UK Parliament unilaterally prorogued the Parliament of Northern Ireland, setting a precedent relevant to contemporary devolved institutions.[221] In practice, it would be politically difficult for the UK Parliament to abolish devolution to the Scottish Parliament and the Senedd, given the political entrenchment created by referendum decisions.[222] The political constraints placed upon the UK Parliament's power to interfere with devolution in Northern Ireland are even greater than in relation to Scotland and Wales, given that devolution in Northern Ireland rests upon an international agreement with the Government of Ireland.[223]

Law and criminal justice

The United Kingdom does not have a single legal system as Article 19 of the 1706 Treaty of Union provided for the continuation of Scotland's separate legal system.[224] Today the UK has three distinct systems of law: English law, Northern Ireland law and Scots law. A new Supreme Court of the United Kingdom came into being in October 2009 to replace the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords.[225][226] The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, including the same members as the Supreme Court, is the highest court of appeal for several independent Commonwealth countries, the British Overseas Territories and the Crown Dependencies.[227]

Both English law, which applies in England and Wales, and Northern Ireland law are based on common-law principles.[228] The essence of common law is that, subject to statute, the law is developed by judges in courts, applying statute, precedent and common sense to the facts before them to give explanatory judgements of the relevant legal principles, which are reported and binding in future similar cases (stare decisis).[229] The courts of England and Wales are headed by the Senior Courts of England and Wales, consisting of the Court of Appeal, the High Court of Justice (for civil cases) and the Crown Court (for criminal cases). The Supreme Court is the highest court in the land for both criminal and civil appeal cases in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and any decision it makes is binding on every other court in the same jurisdiction, often having a persuasive effect in other jurisdictions.[230]

Scots law is a hybrid system based on both common-law and civil-law principles. The chief courts are the Court of Session, for civil cases,[231] and the High Court of Justiciary, for criminal cases.[232] The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom serves as the highest court of appeal for civil cases under Scots law.[233] Sheriff courts deal with most civil and criminal cases including conducting criminal trials with a jury, known as sheriff solemn court, or with a sheriff and no jury, known as sheriff summary Court.[234] The Scots legal system is unique in having three possible verdicts for a criminal trial: "guilty", "not guilty" and "not proven". Both "not guilty" and "not proven" result in an acquittal.[235]

Crime in England and Wales increased in the period between 1981 and 1995, though since that peak there has been an overall fall of 66 per cent in recorded crime from 1995 to 2015,[236] according to crime statistics. The prison population of England and Wales has increased to 86,000, giving England and Wales the highest rate of incarceration in Western Europe at 148 per 100,000.[237][238] Her Majesty's Prison Service, which reports to the Ministry of Justice, manages most of the prisons within England and Wales. The murder rate in England and Wales has stabilised in the first half of the 2010s with a murder rate around 1 per 100,000 which is half the peak in 2002 and similar to the rate in the 1980s[239] Crime in Scotland fell slightly in 2014/2015 to its lowest level in 39 years in with 59 killings for a murder rate of 1.1 per 100,000. Scotland's prisons are overcrowded but the prison population is shrinking.[240]

Foreign relations

.jpg.webp)

The UK is a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, a member of NATO, the Commonwealth of Nations, the G7 finance ministers, the G7 forum, the G20, the OECD, the WTO, the Council of Europe and the OSCE.[241] The UK is said to have a "Special Relationship" with the United States and a close partnership with France – the "Entente cordiale" – and shares nuclear weapons technology with both countries;[242][243] the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance is considered to be the oldest binding military alliance in the world. The UK is also closely linked with the Republic of Ireland; the two countries share a Common Travel Area and co-operate through the British-Irish Intergovernmental Conference and the British-Irish Council. Britain's global presence and influence is further amplified through its trading relations, foreign investments, official development assistance and military engagements.[244] Canada, Australia and New Zealand, all of which are former colonies of the British Empire, are the most favourably viewed countries in the world by British people.[245][246]

Military

_underway_in_the_Atlantic_Ocean_on_17_October_2019_(191017-N-QI061-2210).JPG.webp)

Her Majesty's Armed Forces consist of three professional service branches: the Royal Navy and Royal Marines (forming the Naval Service), the British Army and the Royal Air Force.[247] The armed forces of the United Kingdom are managed by the Ministry of Defence and controlled by the Defence Council, chaired by the Secretary of State for Defence. The Commander-in-Chief is the British monarch, to whom members of the forces swear an oath of allegiance.[248] The Armed Forces are charged with protecting the UK and its overseas territories, promoting the UK's global security interests and supporting international peacekeeping efforts. They are active and regular participants in NATO, including the Allied Rapid Reaction Corps, as well as the Five Power Defence Arrangements, RIMPAC and other worldwide coalition operations. Overseas garrisons and facilities are maintained in Ascension Island, Bahrain, Belize, Brunei, Canada, Cyprus, Diego Garcia, the Falkland Islands, Germany, Gibraltar, Kenya, Oman, Qatar and Singapore.[249][250]

The British armed forces played a key role in establishing the British Empire as the dominant world power in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries. By emerging victorious from conflicts, Britain has often been able to decisively influence world events. Since the end of the British Empire, the UK has remained a major military power. Following the end of the Cold War, defence policy has a stated assumption that "the most demanding operations" will be undertaken as part of a coalition.[251]

According to sources which include the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute and the International Institute for Strategic Studies, the UK has either the fourth- or the fifth-highest military expenditure. Total defence spending amounts to 2.0 per cent of national GDP.[252]

Economy

Overview

The UK has a partially regulated market economy.[253] Based on market exchange rates, the UK is today the fifth-largest economy in the world and the second-largest in Europe after Germany. HM Treasury, led by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, is responsible for developing and executing the government's public finance policy and economic policy. The Bank of England is the UK's central bank and is responsible for issuing notes and coins in the nation's currency, the pound sterling. Banks in Scotland and Northern Ireland retain the right to issue their own notes, subject to retaining enough Bank of England notes in reserve to cover their issue. The pound sterling is the world's third-largest reserve currency (after the US dollar and the euro).[254] Since 1997 the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee, headed by the Governor of the Bank of England, has been responsible for setting interest rates at the level necessary to achieve the overall inflation target for the economy that is set by the Chancellor each year.[255]

The UK service sector makes up around 79 per cent of GDP.[256] London is one of the world's largest financial centres, ranking 2nd in the world, behind New York City, in the Global Financial Centres Index in 2020.[257] London also has the largest city GDP in Europe.[258] Edinburgh ranks 17th in the world, and 6th in Western Europe in the Global Financial Centres Index in 2020.[257] Tourism is very important to the British economy; with over 27 million tourists arriving in 2004, the United Kingdom is ranked as the sixth major tourist destination in the world and London has the most international visitors of any city in the world.[259][260] The creative industries accounted for 7 per cent GVA in 2005 and grew at an average of 6 per cent per annum between 1997 and 2005.[261]

Following the United Kingdom's withdrawal from the European Union, the functioning of the UK internal economic market is enshrined by the United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020 which ensures trade in goods and services continues without internal barriers across the four countries of the United Kingdom.[262][263]

The Industrial Revolution started in the UK with an initial concentration on the textile industry,[264] followed by other heavy industries such as shipbuilding, coal mining and steelmaking.[265][266] British merchants, shippers and bankers developed overwhelming advantage over those of other nations allowing the UK to dominate international trade in the 19th century.[267][268] As other nations industrialised, coupled with economic decline after two world wars, the United Kingdom began to lose its competitive advantage and heavy industry declined, by degrees, throughout the 20th century. Manufacturing remains a significant part of the economy but accounted for only 16.7 per cent of national output in 2003.[269]

Jaguar cars are designed, developed and manufactured in the UK

The automotive industry employs around 800,000 people, with a turnover in 2015 of £70 billion, generating £34.6 billion of exports (11.8 per cent of the UK's total export goods). In 2015, the UK produced around 1.6 million passenger vehicles and 94,500 commercial vehicles. The UK is a major centre for engine manufacturing: in 2015 around 2.4 million engines were produced. The UK motorsport industry employs around 41,000 people, comprises around 4,500 companies and has an annual turnover of around £6 billion.[270]

The aerospace industry of the UK is the second- or third-largest national aerospace industry in the world depending upon the method of measurement and has an annual turnover of around £30 billion.[271]

.jpg.webp)

BAE Systems plays a critical role in some of the world's biggest defence aerospace projects. In the UK, the company makes large sections of the Typhoon Eurofighter and assembles the aircraft for the Royal Air Force. It is also a principal subcontractor on the F35 Joint Strike Fighter – the world's largest single defence project – for which it designs and manufactures a range of components. It also manufactures the Hawk, the world's most successful jet training aircraft.[272] Airbus UK also manufactures the wings for the A400 m military transporter. Rolls-Royce is the world's second-largest aero-engine manufacturer. Its engines power more than 30 types of commercial aircraft and it has more than 30,000 engines in service in the civil and defence sectors.

The UK space industry was worth £9.1bn in 2011 and employed 29,000 people. It is growing at a rate of 7.5 per cent annually, according to its umbrella organisation, the UK Space Agency. In 2013, the British Government pledged £60 m to the Skylon project: this investment will provide support at a "crucial stage" to allow a full-scale prototype of the SABRE engine to be built.

The pharmaceutical industry plays an important role in the UK economy and the country has the third-highest share of global pharmaceutical R&D expenditures.[273][274]

Agriculture is intensive, highly mechanised and efficient by European standards, producing about 60 per cent of food needs with less than 1.6 per cent of the labour force (535,000 workers).[275] Around two-thirds of production is devoted to livestock, one-third to arable crops. The UK retains a significant, though much reduced fishing industry. It is also rich in a number of natural resources including coal, petroleum, natural gas, tin, limestone, iron ore, salt, clay, chalk, gypsum, lead, silica and an abundance of arable land.[276]

In the final quarter of 2008, the UK economy officially entered recession for the first time since 1991.[280] Following the likes of the United States, France and many major economies, in 2013, the UK lost its top AAA credit rating for the first time since 1978 with Moodys and Fitch credit agency, but, unlike the other major economies, retained its triple A rating with Standard & Poor's.[281][282] By the end of 2014, UK growth was the fastest in both the G7 and in Europe,[283][284] and by September 2015, the unemployment rate was down to a seven-year low of 5.3 per cent.[285] In 2020, coronavirus lockdown measures caused the UK economy to suffer its biggest slump on record, shrinking by 20.4% between April and June compared to the first three months of the year, to push it officially into recession for the first time in 11 years.[286]

Since the 1980s, UK economic inequality, like Canada, Australia and the United States, has grown faster than in other developed countries.[287][288] The poverty line in the UK is commonly defined as being 60 per cent of the median household income.[note 16] The Office for National Statistics has estimated that in 2011, 14 million people were at risk of poverty or social exclusion, and that one person in 20 (5.1 per cent) was experiencing "severe material depression",[289] up from 3 million people in 1977.[290][291] Although the UK does not have an official poverty measure, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and the Social Metrics Commission estimate, based on government data, that there are 14 million people in poverty in the UK.[292][293] 1.5 million people experienced destitution in 2017.[294] In 2018, the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights visited the UK and found that government policies and cuts to social support are "entrenching high levels of poverty and inflicting unnecessary misery in one of the richest countries in the world."[295] His final 2019 report found that the UK government was doubling down on policies that have "led to the systematic immiseration of millions across Great Britain" and that sustained and widespread cuts to social support "amount to retrogressive measures in clear violation of the United Kingdom’s human rights obligations."[296]

The UK has an external debt of $9.6 trillion dollars, which is the second-highest in the world after the US. As a percentage of GDP, external debt is 408 per cent, which is the third-highest in the world after Luxembourg and Iceland.[297][298][299][300][301]

Science and technology

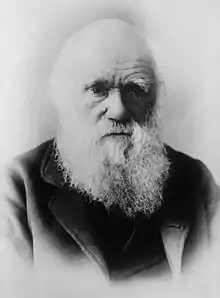

England and Scotland were leading centres of the Scientific Revolution from the 17th century.[302] The United Kingdom led the Industrial Revolution from the 18th century,[264] and has continued to produce scientists and engineers credited with important advances.[303] Major theorists from the 17th and 18th centuries include Isaac Newton, whose laws of motion and illumination of gravity have been seen as a keystone of modern science;[304] from the 19th century Charles Darwin, whose theory of evolution by natural selection was fundamental to the development of modern biology, and James Clerk Maxwell, who formulated classical electromagnetic theory; and more recently Stephen Hawking, who advanced major theories in the fields of cosmology, quantum gravity and the investigation of black holes.[305]

Major scientific discoveries from the 18th century include hydrogen by Henry Cavendish;[306] from the 20th century penicillin by Alexander Fleming,[307] and the structure of DNA, by Francis Crick and others.[308] Famous British engineers and inventors of the Industrial Revolution include James Watt, George Stephenson, Richard Arkwright, Robert Stephenson and Isambard Kingdom Brunel.[309] Other major engineering projects and applications by people from the UK include the steam locomotive, developed by Richard Trevithick and Andrew Vivian;[310] from the 19th century the electric motor by Michael Faraday, the first computer designed by Charles Babbage,[311] the first commercial electrical telegraph by William Fothergill Cooke and Charles Wheatstone,[312] the incandescent light bulb by Joseph Swan,[313] and the first practical telephone, patented by Alexander Graham Bell;[314] and in the 20th century the world's first working television system by John Logie Baird and others,[315] the jet engine by Frank Whittle, the basis of the modern computer by Alan Turing, and the World Wide Web by Tim Berners-Lee.[316]

Scientific research and development remains important in British universities, with many establishing science parks to facilitate production and co-operation with industry.[317] Between 2004 and 2008 the UK produced 7 per cent of the world's scientific research papers and had an 8 per cent share of scientific citations, the third and second-highest in the world (after the United States and China, respectively).[318] Scientific journals produced in the UK include Nature, the British Medical Journal and The Lancet.[319]

Transport

A radial road network totals 29,145 miles (46,904 km) of main roads, 2,173 miles (3,497 km) of motorways and 213,750 miles (344,000 km) of paved roads.[153] The M25, encircling London, is the largest and busiest bypass in the world.[322] In 2009 there were a total of 34 million licensed vehicles in Great Britain.[323]

The UK has a railway network of 10,072 miles (16,209 km) in Great Britain and 189 miles (304 km) in Northern Ireland. Railways in Northern Ireland are operated by NI Railways, a subsidiary of state-owned Translink. In Great Britain, the British Rail network was privatised between 1994 and 1997, which was followed by a rapid rise in passenger numbers following years of decline, although the factors behind this are disputed. The UK was ranked eighth among national European rail systems in the 2017 European Railway Performance Index assessing intensity of use, quality of service and safety.[324] Network Rail owns and manages most of the fixed assets (tracks, signals etc.). Around twenty, mostly privately owned, train operating companies operate passenger trains. In 2015, 1.68 billion passengers were carried.[325][326] There are about 1,000 freight trains in daily operation.[153] HS2, a new high-speed railway line, is estimated to cost £56 billion.[327] Crossrail, under construction in London, is Europe's largest construction project with a £15 billion projected cost.[328][329]

In the year from October 2009 to September 2010 UK airports handled a total of 211.4 million passengers.[330] In that period the three largest airports were London Heathrow Airport (65.6 million passengers), Gatwick Airport (31.5 million passengers) and London Stansted Airport (18.9 million passengers).[330] London Heathrow Airport, located 15 miles (24 km) west of the capital, has the most international passenger traffic of any airport in the world[320][321] and is the hub for the UK flag carrier British Airways, as well as Virgin Atlantic.[331]

Energy

In 2006, the UK was the world's ninth-largest consumer of energy and the 15th-largest producer.[332] The UK is home to a number of large energy companies, including two of the six oil and gas "supermajors" – BP and Royal Dutch Shell.[333][334]

In 2013, the UK produced 914 thousand barrels per day (bbl/d) of oil and consumed 1,507 thousand bbl/d.[335][336] Production is now in decline and the UK has been a net importer of oil since 2005.[337] In 2010 the UK had around 3.1 billion barrels of proven crude oil reserves, the largest of any EU member state.[337]

In 2009, the UK was the 13th-largest producer of natural gas in the world and the largest producer in the EU.[338] Production is now in decline and the UK has been a net importer of natural gas since 2004.[338]

Coal production played a key role in the UK economy in the 19th and 20th centuries. In the mid-1970s, 130 million tonnes of coal were produced annually, not falling below 100 million tonnes until the early 1980s. During the 1980s and 1990s the industry was scaled back considerably. In 2011, the UK produced 18.3 million tonnes of coal.[339] In 2005 it had proven recoverable coal reserves of 171 million tons.[339] The UK Coal Authority has stated there is a potential to produce between 7 billion tonnes and 16 billion tonnes of coal through underground coal gasification (UCG) or 'fracking',[340] and that, based on current UK coal consumption, such reserves could last between 200 and 400 years.[341] Environmental and social concerns have been raised over chemicals getting into the water table and minor earthquakes damaging homes.[342][343]

In the late 1990s, nuclear power plants contributed around 25 per cent of total annual electricity generation in the UK, but this has gradually declined as old plants have been shut down and ageing-related problems affect plant availability. In 2012, the UK had 16 reactors normally generating about 19 per cent of its electricity. All but one of the reactors will be retired by 2023. Unlike Germany and Japan, the UK intends to build a new generation of nuclear plants from about 2018.[344]

The total of all renewable electricity sources provided for 14.9 per cent of the electricity generated in the United Kingdom in 2013,[345] reaching 53.7 TWh of electricity generated. The UK is one of the best sites in Europe for wind energy, and wind power production is its fastest growing supply, in 2014 it generated 9.3 per cent of the UK's total electricity.[346][347][348]

Water supply and sanitation

Access to improved water supply and sanitation in the UK is universal. It is estimated that 96.7 per cent of households are connected to the sewer network.[349] According to the Environment Agency, total water abstraction for public water supply in the UK was 16,406 megalitres per day in 2007.[350]

In England and Wales water and sewerage services are provided by 10 private regional water and sewerage companies and 13 mostly smaller private "water only" companies. In Scotland water and sewerage services are provided by a single public company, Scottish Water. In Northern Ireland water and sewerage services are also provided by a single public entity, Northern Ireland Water.[351]

Demographics

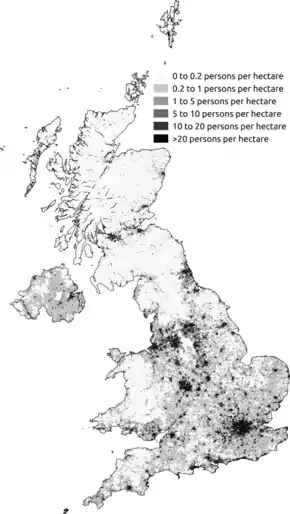

A census is taken simultaneously in all parts of the UK every 10 years.[352] In the 2011 census the total population of the United Kingdom was 63,181,775.[353] It is the fourth-largest in Europe (after Russia, Germany and France), the fifth-largest in the Commonwealth and the 22nd-largest in the world. In mid-2014 and mid-2015 net long-term international migration contributed more to population growth. In mid-2012 and mid-2013 natural change contributed the most to population growth.[354] Between 2001 and 2011 the population increased by an average annual rate of approximately 0.7 per cent.[353] This compares to 0.3 per cent per year in the period 1991 to 2001 and 0.2 per cent in the decade 1981 to 1991.[355] The 2011 census also confirmed that the proportion of the population aged 0–14 has nearly halved (31 per cent in 1911 compared to 18 in 2011) and the proportion of older people aged 65 and over has more than tripled (from 5 per cent to 16 per cent).[353]

England's population in 2011 was 53 million.[356] It is one of the most densely populated countries in the world, with 420 people resident per square kilometre in mid-2015,[354] with a particular concentration in London and the south-east.[357] The 2011 census put Scotland's population at 5.3 million,[358] Wales at 3.06 million and Northern Ireland at 1.81 million.[356]

In 2017 the average total fertility rate (TFR) across the UK was 1.74 children born per woman.[359] While a rising birth rate is contributing to population growth, it remains considerably below the baby boom peak of 2.95 children per woman in 1964,[360] or the high of 6.02 children born per woman in 1815,[361] below the replacement rate of 2.1, but higher than the 2001 record low of 1.63.[362] In 2011, 47.3 per cent of births in the UK were to unmarried women.[363] The Office for National Statistics published a bulletin in 2015 showing that, out of the UK population aged 16 and over, 1.7 per cent identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual (2.0 per cent of males and 1.5 per cent of females); 4.5 per cent of respondents responded with "other", "I don't know", or did not respond.[364] In 2018 the median age of the UK population was 41.7 years.[365]

Ethnic groups

Historically, indigenous British people were thought to be descended from the various ethnic groups that settled there before the 12th century: the Celts, Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Norse and the Normans. Welsh people could be the oldest ethnic group in the UK.[369] A 2006 genetic study shows that more than 50 per cent of England's gene pool contains Germanic Y chromosomes.[370] Another 2005 genetic analysis indicates that "about 75 per cent of the traceable ancestors of the modern British population had arrived in the British isles by about 6,200 years ago, at the start of the British Neolithic or Stone Age", and that the British broadly share a common ancestry with the Basque people.[371][372][373]

The UK has a history of non-white immigration with Liverpool having the oldest Black population in the country dating back to at least the 1730s during the period of the African slave trade. During this period it is estimated the Afro-Caribbean population of Great Britain was 10,000 to 15,000[374] which later declined due to the abolition of slavery.[375][376] The UK also has the oldest Chinese community in Europe, dating to the arrival of Chinese seamen in the 19th century.[377] In 1950 there were probably fewer than 20,000 non-white residents in Britain, almost all born overseas.[378] In 1951 there were an estimated 94,500 people living in Britain who had been born in South Asia, China, Africa and the Caribbean, just under 0.2 per cent of the UK population. By 1961 this number had more than quadrupled to 384,000, just over 0.7 per cent of the United Kingdom population.[379]

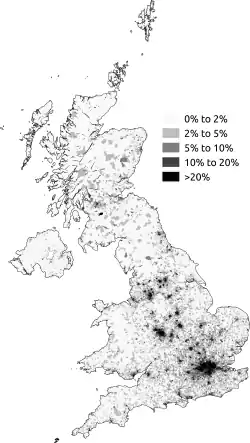

Since 1948 substantial immigration from Africa, the Caribbean and South Asia has been a legacy of ties forged by the British Empire.[380] Migration from new EU member states in Central and Eastern Europe since 2004 has resulted in growth in these population groups, although some of this migration has been temporary.[381] Since the 1990s, there has been substantial diversification of the immigrant population, with migrants to the UK coming from a much wider range of countries than previous waves, which tended to involve larger numbers of migrants coming from a relatively small number of countries.[382][383][384]

| Ethnic group | Population (absolute) | Population (per cent) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001[385] | 2011 | 2011[386] | ||

| White | 54,153,898

(92.14% |

55,010,359

(87.1%) |

87.1 % | |

| White: Gypsy / Traveller / Irish Traveller[note 17] | – | 63,193 | 0.1 % | |

| Asian / Asian British | Indian | 1,053,411 | 1,451,862 | 2.3 % |

| Pakistani | 747,285 | 1,174,983 | 1.9 % | |

| Bangladeshi | 283,063 | 451,529 | 0.7 % | |

| Chinese | 247,403 | 433,150 | 0.7 % | |

| other Asian | 247,664 | 861,815 | 1.4 % | |

| Black / African / Caribbean / Black British | 1,148,738 | 1,904,684 [note 18] | 3.0 % | |

| mixed / multiple ethnic groups | 677,117 | 1,250,229 | 2.0 % | |

| other ethnic group | 230,615 | 580,374 | 0.9 % | |

| Total | 58,789,194 | 63,182,178 | 100.0 % | |

Academics have argued that the ethnicity categories employed in British national statistics, which were first introduced in the 1991 census, involve confusion between the concepts of ethnicity and race.[389][390] In 2011, 87.2 per cent of the UK population identified themselves as white, meaning 12.8 per cent of the UK population identify themselves as of one of number of ethnic minority groups.[386] In the 2001 census, this figure was 7.9 per cent of the UK population.[391]

Because of differences in the wording of the census forms used in England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, data on the Other White group is not available for the UK as a whole, but in England and Wales this was the fastest growing group between the 2001 and 2011 censuses, increasing by 1.1 million (1.8 percentage points).[392] Amongst groups for which comparable data is available for all parts of the UK level, the Other Asian category increased from 0.4 per cent to 1.4 per cent of the population between 2001 and 2011, while the Mixed category rose from 1.2 per cent to 2 per cent.[386]

Ethnic diversity varies significantly across the UK. 30.4 per cent of London's population and 37.4 per cent of Leicester's was estimated to be non-white in 2005,[393][394] whereas less than 5 per cent of the populations of North East England, Wales and the South West were from ethnic minorities, according to the 2001 census.[395] In 2016, 31.4 per cent of primary and 27.9 per cent of secondary pupils at state schools in England were members of an ethnic minority.[396] The 1991 census was the first UK census to have a question on ethnic group. In the 1991 UK census 94.1 per cent of people reported themselves as being White British, White Irish or White Other with 5.9 per cent of people reporting themselves as coming from other minority groups.[397]

Languages

The UK's de facto official language is English.[400][401] It is estimated that 95 per cent of the UK's population are monolingual English speakers.[402] 5.5 per cent of the population are estimated to speak languages brought to the UK as a result of relatively recent immigration.[402] South Asian languages are the largest grouping which includes Punjabi, Urdu, Bengali/Sylheti, Hindi and Gujarati.[403] According to the 2011 census, Polish has become the second-largest language spoken in England and has 546,000 speakers.[404] In 2019, some three quarters of a million people spoke little or no English.[405]

Three indigenous Celtic languages are spoken in the UK: Welsh, Irish and Scottish Gaelic. Cornish, which became extinct as a first language in the late 18th century, is subject to revival efforts and has a small group of second language speakers.[406][407][2][408] In the 2011 Census, approximately one-fifth (19 per cent) of the population of Wales said they could speak Welsh,[409][410] an increase from the 1991 Census (18 per cent).[411] In addition, it is estimated that about 200,000 Welsh speakers live in England.[412] In the same census in Northern Ireland 167,487 people (10.4 per cent) stated that they had "some knowledge of Irish" (see Irish language in Northern Ireland), almost exclusively in the nationalist (mainly Catholic) population. Over 92,000 people in Scotland (just under 2 per cent of the population) had some Gaelic language ability, including 72 per cent of those living in the Outer Hebrides.[413] The number of children being taught either Welsh or Scottish Gaelic is increasing.[414] Among emigrant-descended populations some Scottish Gaelic is still spoken in Canada (principally Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island),[415] and Welsh in Patagonia, Argentina.[416]

Scots, a language descended from early northern Middle English, has limited recognition alongside its regional variant, Ulster Scots in Northern Ireland, without specific commitments to protection and promotion.[2][417]

It is compulsory for pupils to study a second language up to the age of 14 in England.[418] French and German are the two most commonly taught second languages in England and Scotland. All pupils in Wales are either taught Welsh as a second language up to age 16, or are taught in Welsh as a first language.[419]

Religion

Forms of Christianity have dominated religious life in what is now the United Kingdom for over 1,400 years.[420] Although a majority of citizens still identify with Christianity in many surveys, regular church attendance has fallen dramatically since the middle of the 20th century,[421] while immigration and demographic change have contributed to the growth of other faiths, most notably Islam.[422] This has led some commentators to variously describe the UK as a multi-faith,[423] secularised,[424] or post-Christian society.[425]

In the 2001 census 71.6 per cent of all respondents indicated that they were Christians, with the next largest faiths being Islam (2.8 per cent), Hinduism (1.0 per cent), Sikhism (0.6 per cent), Judaism (0.5 per cent), Buddhism (0.3 per cent) and all other religions (0.3 per cent).[426] 15 per cent of respondents stated that they had no religion, with a further 7 per cent not stating a religious preference.[427] A Tearfund survey in 2007 showed only one in 10 Britons actually attend church weekly.[428] Between the 2001 and 2011 census there was a decrease in the number of people who identified as Christian by 12 per cent, whilst the percentage of those reporting no religious affiliation doubled. This contrasted with growth in the other main religious group categories, with the number of Muslims increasing by the most substantial margin to a total of about 5 per cent.[7] The Muslim population has increased from 1.6 million in 2001 to 2.7 million in 2011, making it the second-largest religious group in the United Kingdom.[429]

In a 2016 survey conducted by BSA (British Social Attitudes) on religious affiliation; 53 per cent of respondents indicated 'no religion', while 41 per cent indicated they were Christians, followed by 6 per cent who affiliated with other religions (e.g. Islam, Hinduism, Judaism, etc.).[430] Among Christians, adherents to the Church of England constituted 15 per cent, Roman Catholic Church 9 per cent, and other Christians (including Presbyterians, Methodists, other Protestants, as well as Eastern Orthodox), 17 per cent.[430] 71 per cent of young people aged 18––24 said they had no religion.[430]

The Church of England is the established church in England.[431] It retains a representation in the UK Parliament and the British monarch is its Supreme Governor.[432] In Scotland, the Church of Scotland is recognised as the national church. It is not subject to state control, and the British monarch is an ordinary member, required to swear an oath to "maintain and preserve the Protestant Religion and Presbyterian Church Government" upon his or her accession.[433][434] The Church in Wales was disestablished in 1920 and, as the Church of Ireland was disestablished in 1870 before the partition of Ireland, there is no established church in Northern Ireland.[435] Although there are no UK-wide data in the 2001 census on adherence to individual Christian denominations, it has been estimated that 62 per cent of Christians are Anglican, 13.5 per cent Catholic, 6 per cent Presbyterian, and 3.4 per cent Methodist, with small numbers of other Protestant denominations such as Plymouth Brethren, and Orthodox churches.[436]

Migration