Upper-limb surgery in tetraplegia

Upper-limb surgery in tetraplegia includes a number of surgical interventions that can help improve the quality of life of a patient with tetraplegia.

| Upper-limb surgery in tetraplegia | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | neurosurgeon |

Loss of upper-limb function in patients with following a spinal cord injury is a major barrier to regain autonomy. The functional abilities of a tetraplegic patient increase substantially for instance if the patient can extend the elbow. This can increase the workspace and give a better use of a manual wheelchair. To be able to hold objects a patient needs to have a functional pinch grip, this can be useful for performing daily living activities.[1] A large survey in patients with tetraplegia demonstrated that these patients give preference to improving upper extremity function above other lost functions like being able to walk or sexual function.[1]

Surgical procedures do exist to improve the function of the tetraplegic patient's arms, but these procedures are performed in fewer than 10% of the tetraplegic patients.[2] Each tetraplegic patient is unique, and therefore surgical indication should be based on the remaining physical abilities, wishes and expectations of the patient.[3]

In 2007 a resolution was presented and accepted at the world congress in reconstructive hand surgery and rehabilitation in tetraplegia, that stated that every patient with tetraplegia should be examined and informed about the options for reconstructive surgery of the tetraplegic arms and hands. This resolution demonstrates mostly the necessity to increase the awareness on this subject amongst physicians.[4]

History

Reconstructive surgery of the upper limb in tetraplegic patients began during the mid-20th century. The first attempts at regaining gripping function of the hand probably took place in Europe at the end of the 1920s[5] with the construction of flexor-hinge splints.[6]

In the early 1940s, a surgeon called Sterling Bunnell (1882–1957) was probably one of the first to refer to the reconstruction of gripping function for the tetraplegic hand. He described surgeries of combining tenodeses and tendon transfers to restore hand function. He also advocated transferring the m. brachioradialis to the wrist extensors when these muscles are paralyzed.

In the 1950s, understanding of the tenodesis effect (See Tenodesis grasp) influenced the development of surgical techniques such as the static flexor tenodesis. These procedures provided the basic functions of grasp and pinch.[7][8][9] Tendon transfers were developed to accomplish both digital release and gripping functions in two surgical stages. The originators of these procedures were Lipscomb et al. [20], Zancolli,[10][11][12] House et al.[13][14] House et al. contributed important clinical investigations while showing the value of different surgical procedures.

According to Zancolli,[11] transfer of the m. brachioradialis to the m. extensor carpi radialis tendons was proposed by Vulpius and Stoffel in 1920. In tetraplegia, this was first proposed by Wilson.[11] and first described fully by Freehafer.[7]

In 1967, Alvin Freehafer of Cleveland, Ohio, contributed valuable ideas towards achieving independence in the arms of tetraplegic patients. He and his team published the results of six patients who underwent transfer of the m. brachioradialis to restore active wrist extension.[15] In 1974, Freehafer et al.[16] recommended opposition transfers and finger-flexion transfers.

In 1971, surgery of the tetraplegic upper limb experienced a revival after Moberg’s clinical investigations. His main contributions were (1) to restore elbow extension through transfer of the posterior deltoid to triceps (the initial procedure); and (2) to reconstruct a key pinch.[17] Moberg’s idea of posterior deltoid transfer to restore elbow extension has been used extensively by many surgeons, such as Bryan[18] and DeBenedetti.[19]

In 1983, Douglas Lamb of Edinburgh, Scotland, gave great headway to surgery of the tetraplegic upper extremity when Lamb and Chan recommended reconstruction of elbow extension by transferring the posterior deltoid to the triceps according to Moberg’s technique, which was published in 1975.[20]

A publication by Friedenberg[21] was the starting point for future indications of biceps-to-triceps transfers, including those of Zancolli,[22] Hentz et al., Kuts et al., Allieu et al. and Revol et al.

Another major change was the change to one-step procedures, reconstructiong opening and closing phases at the same time. Especially Jan Friden, from Gothenburg, with major experience in this area championed this thought, partially driven by the transport problems in Sweden during winter, it saved the patients an operation and minimized hospital stay.

The development of hand surgery for tetraplegia has received important contributions through published reports and by the international conferences initiated with the influence of Erik Moberg from Goteborg, Sweden. Conferences have been of great interest because of the convergences of hand surgeons interested in the field, promoting discussion and comparison of different surgical methods and experiences.[23]

Goals for surgery

A common goal of surgical reconstruction of the arms in patients with tetraplegia is to restore elbow extension, key pinch and palmar grip. Restoration of these functions, results in increasing a patient's independence.[24]

Elbow extension is an important part of upper limb surgical reconstruction in patients with tetraplegia. Although gravity can extend the arm, active elbow extension is needed to maintain a stable arm while extended in space. This is needed to reach for something or replace an object.[25] Other functional gains include: increasing available workspace, performing pressure relief maneuvers, propelling a manual wheelchair, enhancing self-care and leisure activities, and promoting independent transfer. Elbow extension against gravity further enhances these activities above the shoulder level and reachable workspace.[26]

The key pinch is a simple grasp in which the thumb applies force to an object to hold it against the lateral side of the index finger.[24] Restoring this function allows a patient to hold objects such as a fork or pen that are necessary for activities of daily living such as eating, self-grooming and self-catheterization.

Palmar grip allows the patient to grasp objects in the palm of the hand and secure the object by flexing the fingers at the metacarpal joint. This gives the patient the possibility to hold objects such as a cup and also permits use of the hand for wheelchair propulsion.[1] A social aspect of regaining the palmar grip is that the patient is able to give a handshake.

Classification of the injury

Spinal cord injuries are classified as complete and incomplete by the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) classification. The ASIA scale grades patients based on their functional impairment as a result of the injury, grading a patient from A to D. This has considerable consequences for surgical planning and therapy.[27]

More information on classification of tetraplegia can be found on the tetraplegia page.

Pre-operative assessment

A group of hand surgeons realized in the 1970s that the level of injury did not predict the number of available muscles in the upper limb very well. Therefore, the international classification was established in 1979, at the Edinburgh meeting. It was called “The international classification (IC) of hand surgery in tetraplegic patients” (table 2) and it describes the number of possible transferable muscles. To measure and evaluate hand strength each muscle is tested and all muscles with a BMRC grade of M4 or more are recorded.[3]

Table 2:

International Classification of Hand surgery in Tetraplegic Patients[3]

| Group | M4 (BMRC) Muscles | |

|---|---|---|

| IC 0 | No muscle below the elbow | |

| High-level Tetraplegia | ||

| IC 1 | m. brachioradialis | |

| IC 2 | m. extensor carpi radialis longus | |

| Mid-level tetraplegia | ||

| IC 3 | m. extensor carpi radialis brevis | |

| IC 4 | m. pronator teres | |

| IC 5 | m. flexor carpi radialis | |

| Low-level tetraplegia | ||

| IC 6 | finger extensors | |

| IC 7 | thumb extensor | |

| IC 8 | partial digital flexors | |

| IC 9 | lack only intrinsics | |

| IC X | exceptions |

A muscle not included in the International Classification, but of great importance, is the triceps muscle. When assessing a patient pre-operatively the triceps strength must also be recorded. An active triceps means a patient can reach in space, and the elbow can be stabilized against gravity and against other muscles to be transferred. (see further)[3]

Furthermore, to classify patients it is essential to record sensation in at least the thumb and index pulpa. Patients with a two point discrimination of less than 10mm are classified as cutaneous sensation (OCu) and patients with a two-point discrimination of more than 10mm are classified as ocular sensation (O) (meaning that control of the to be operated limb cannot be performed by normal sensation, but is controlled visually).[28]

Therefore, patients are classified as: O or OCu, IC gr(0-X), Triceps + or –

For example: a patient has sensation of 8 mm in thumb and index pulpa, and has a good brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis and a pronator teres (all of M4) but no Triceps. This patient is classified as OCu 4, Tr -.

Patient oriented goals

The pre-operative assessment of patients has turned more patient-goal oriented. This means that the patients are asked to define their goals before surgery. In order to evaluate this the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) was developed. This test is based on the World Health Organisation's framework of measuring health and disability: The International Classification of Function(ICF): This framework measures health and disability by means of two lists: a list of body functions and structure, and a list of domains of activity and participation.[29] Functional deficits can be measured according to the level of loss of structure and function, the level of activity limitations, and the level of restriction in social participation. Reaching or gripping represents the integration of strength, sensation and range of motion, and therefore occur at the individual level rather than at the organ system level. For this reason, reaching and gripping are on the ICF level of activities. However, this level includes a broad range of activities, from basic activities (for example grasping and moving objects) to complex activities (such as dressing, grooming). It is useful to make a distinction between basic activities and complex activities.[29]

COPM

As mentioned above, The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) is used to measure a tetraplegic patient's performance and satisfaction before and after upper limb surgery.[26] This is done by identifying important goals of hand surgery and evaluating patient-perceived performance and satisfaction of hand surgery for these goals. Goals are identified through an interview between the therapist and the patient based on past experience. Published reports[26] are provided about the expected outcomes of elbow extension transfers on strength and function of patients with a spinal cord injury. For each goal, the subject rated performance and satisfaction using a 10-point Likert scale, in which 1 was negative (“cannot perform,” “not satisfied”) and 10 was positive (“performs very well,” “very satisfied”). After surgery, performance and satisfaction are rated again for each goal.

A positive change is seen in patient-perceived performance and satisfaction with self-identified goals after tendon transfers. A good example of the use of the COPM can be found in a report published by Scott Kozin,[26] thirty-three goals for surgery were established. Following the biceps-to-triceps transfer, improvement in at least one goal was seen in all patients. Performance and satisfaction were greatly improved (an improvement of at least 4 points) in certain activities of daily living, including reaching for objects, recreational activities, wheelchair propulsion, and transfers. Although improvement was seen in most goals, a reduction was reported in 2 goals (one pertaining to dressing and the other to transfer). After tendon transfers, the total mean score statistically increased from 2.6 to 5.6 for performance (p .001) and from 1.8 to 5.7 for satisfaction (p .001).[26]

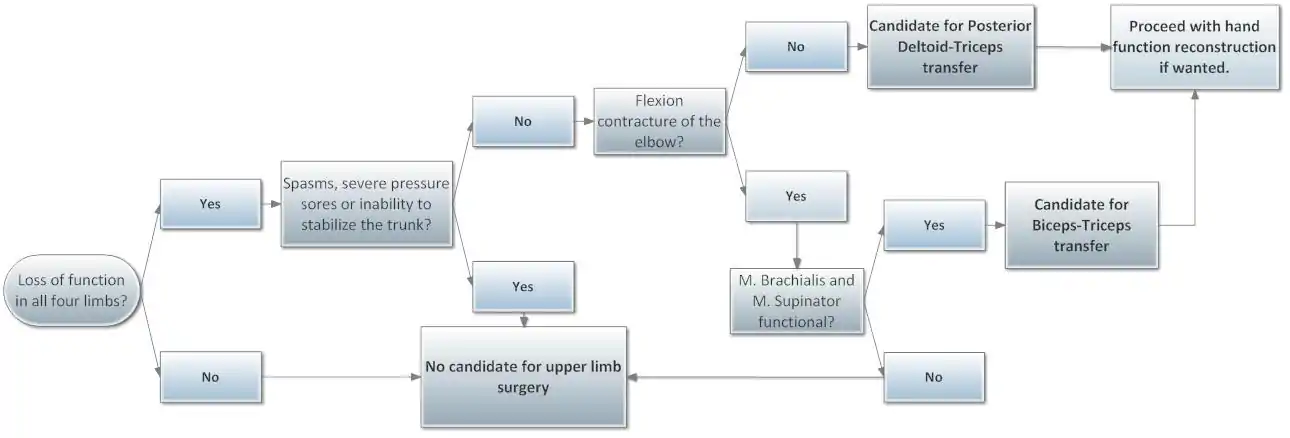

Criteria for surgery

General indications for functional surgery of the hand and arm in tetraplegic patients:

There are different views on optimal timing of surgery after a spinal cord injury. The general consensus is to operate the patient when he or she is neurologically stable. Some surgeons try to operate a patient as early as possible. The advantages of this are that the patient can take advantage of the new functional possibilities before new adjustments and apaptations develop. Other surgeons operate when it becomes feasible. This is usually 12–18 months after injury (can be shortened to 6–7 months) and only after stabilization of motor function. Important spasticity (see further) and neurovegetative complications (i.e. bladder function, bowel function, pulmonary function and pressure sores) must have been treated already. The patient must be able to sit in a wheelchair so that he/she can move the arm against gravity. Usually a compromise is found between the patient’s wishes and the surgeon when timing the surgery.[3]

An indication for biceps-to-triceps surgery is when the patient plateaud for more than 3 months in their motor recovery. It is usually the choice of procedure for patients who have a flexion contractures greater than 45 degrees. The procedure will release the contracture and allows for active flexion by transferring the biceps.[25]

It is important that the psychological condition of the patient is evaluated before surgery. The dramatic change in the patient’s life requires a psychological adjustment. This should be evaluated and addressed before surgery. Follow-up by a psychologist is necessary. Patient must be psychologically ready to understand the surgical planning, aims and possible outcomes. The patient must be motivated, well-informed, in sound psychological condition and must have a precise and realistic need for rehabilitation. Individual factors must be taken into account. (age, profession, hobbies, education, family support and social background). This is especially important in associated brain injury.[3]

Contraindications

Contraindications for surgery are severe pressure sores, severe spasticity, inability to stabilize the trunk.

Spasticity, if present, can be very important. It is not a contraindication per se, but severe spasticity must be treated first depending in which muscle groups it is present. Spascticity can be treated with botox or myotomies. In some cases spastic tone can be useful to facilitate hand grasp and grip. Harmful spasticity that does not respond to medication or surgical treatment is a contraindication. The shoulder muscles, pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi, must be evaluated. The shoulder must not only have good motor condition but also good proprioceptive control. The trophicity and articular condition of the upper limb must also be considered. A poor condition requires a preoperative rehabilitation program.[3]

Before any hand surgery is performed, the patient should be able to actively extend the elbow. Therefore, if there is no active elbow extension, elbow extension reconstruction surgery should precede any hand surgery.

A contraindication specifically for posterior deltoid to triceps transfer is a flexion contracture of the elbow, biceps to triceps transfer might then be a possible transfer for elbow extension reconstruction.

The contraindications for biceps-to-triceps transfer relate to the muscle balance surrounding the elbow. The m. supinator and m. brachialis function is a prerequisite for this surgery. If one of these muscles is nonfunctional the patient will lose forearm supination and elbow flexion if the tendon is transferred.

Surgical procedures – active and passive tendon transfers

In general, reconstruction of the upper limb can only be performed if active elbow extension is present. This stabilizes the elbow and gives the patient a reach. It will also allow the transfer of the other muscles crossing the elbow joint (like the m. brachioradialis and m. extensor carpi radialis longus). It is also an operation whose results allow the patient to gain confidence in the rest of the treatment.[3][4]

Wrist-related tenodesis effect (Tenodesis grasp) means that wrist flexion passively opens the hand and wrist extension passively closes the hand. (see pictures below) Wrist-related tenodesis effect is the key point of any functional surgery in a paralyzed hand, therefore active wrist extension is required and reconstruction of this active wrist extension is of utmost importance for the tetraplegic hand.[30] If no active wrist extension is available (IC group 0 and 1), the brachioradialis (only IC group 1) can be transferred to achieve wrist extension.[30]

Wrist related tenodesis effect

Wrist related tenodesis effect Wrist related tenodesis effect

Wrist related tenodesis effect

Active tendon transfers are possible if m. extensor carpi radialis longus and m. extensor carpi radialis brevis are present. The use of the m. extensor carpi radialis longus and the m. brachioradialis are possible to restore hand function.[30]

Elbow

There are two major techniques used to gain elbow extension.

Deltoid-to-triceps transfer: For this transfer, the posterior part of the deltoid muscle is released from its origin and attached to the triceps muscle (usually by means of a tendon graft or a synthetic graft) leaving the rest of the deltoid muscle intact. This transfer is usually very successful because the line of pull of the posterior deltoid muscle is in the same direction as the triceps muscle. Also, there is hardly any loss of function.[30]

The deltoid muscle is usually innervated by the fifth and sixth cervical nerve roots and is therefore often functional in patients with tetraplegia, though the triceps muscle, which is innervated by the seventh cervical root, is paralysed. Because of the location at the back of the arm, the posterior part of the deltoid muscle can give strength in the same direction as the triceps muscle and is therefore theoretically a good donor to regain elbow extension.

Not only the direction of the strength provided by the donormuscle is important, Smith et al. showed that the matching between the original functional properties of the donor and recipient muscles affects the outcome of the transfer.[31][32] Therefore, Fridén studied the architectural properties of the deltoid and triceps muscle in cadavers and concluded that the posterior deltoid would be a very suitable transfer to provide elbow extension.[4]

Since the tendon of the triceps is not long enough to reach the posterior deltoid muscle, an interposition graft is needed. Different procedures have been described to achieve the transfer. Moberg [5] used free tendon grafts from the long toe extensors to connect the posterior deltoid to the triceps, other interposition grafts have been described, including fascia lata and a triceps tendon turnup.[33][34] One should keep in mind that many patients hold out a hope for a cure and are therefore concerned about incurring a significant donor defect that could cause impairment if they recovered a lowerextremity function.[35] The first part of the surgery should be to make an incision along the posterior border of the deltoid. The muscle is exposed to its insertion on the humerus. Next the part of the muscles that originates from the spina scapulae, the posterior one third to one half, is isolated from the anterior portion of the muscle. The insertion of the posterior deltoid is then elevated of the muscle and the distance between the mobilized deltoid tendon to the olecranon is measured to determine the length of the interposition graft needed. The interposition graft must now be harvested from its donor site. It should be 5 to 10 cm longer than the gap. After this a longitudinal incision should be made over the triceps tendon in which two transverse slits are made. One end of the graft should be wrapped around the posterior deltoid and sutured securely to it, after which the grafted is passed through an intercutaneous tunnel towards the triceps tendon, woven through the transverse slits and sutured securely to the triceps tendon and itself. Once the graft is securely in place, the wound is closed and a long armcast is applied with the elbow at 10 degrees of flexion.

This tendon transfer has a high risk of being stretched, during the postsurgical period. It is extremely important that a challenging and precise post-surgical rehabilitation program is implemented, in order to maximize the results and prevent the tendon from becoming stretched.[36]

Biceps-to-triceps transfer: The biceps muscle can only be used for this transfer if the other elbow flexors are intact (m. brachialis and m. brachioradialis).[30] This procedure is typically performed under general anesthesia but can be performed under supraclavicular brachial plexus blockade. The incision depends on whether there is a contracture that needs to be released. If this is the case a wide exposure of the anterior side of the elbow joint is needed. The distal side of the incision should allow complete dissection of the tendon of the biceps. The primary tendon of the biceps is released from its insertion on the radius and then rerouted medial or lateral. If the ulnar nerve is functional a lateral route is favored to prevent compression, however, the lateral route can cause compression of the radial nerve. A second incision is made to expose the triceps insertion and the triceps is dissected from its insertion on the olecranon. A hole is then drilled in the olecranon and a gauge wire is then looped in the hole. The biceps is routed through a skin tunnel to the posterior side and woven into the triceps tendon to create more length. Then the tendon is inserted to the olecranon.[25]

Hand

Restoration of Key Pinch: In general for Key Pinch the thumb has to be activated. In the lower groups according to the International Classification (IC groups 0–1) this can only be done by means of tenodesis. In IC groups 2 and higher the m. brachioradialis is used to strengthen the thumb flexor.[30] Usually the thumb extensor is fixed to the extensor retinaculum and the CMC1 joint is arthrodesed/fused in the right position.[3]

Restoration of palmar grip: When active wrist extension is present, it must not be weakened. Therefore, the extensor carpi radialis longus can only be used on patients in IC 3 and higher where active extension is supplied by both the extensor carpi radialis longus and the extensor carpi radialis brevis. In IC 2 patients active extension of the wrist depends only on the m. extensor carpi radialis longus, therefore this muscle must not be used for a transfer in this group of patients.[30]

The brachioradialis muscle is a versatile motor muscle and is used for different transfers in tetraplegic patients. In IC 1 it is used to restore wrist extension, while in IC 2–8 it is used to restore finger extension (m.extensor digitorum communis) and finger (m.flexor digitorum profundus) or thumb flexion (m.flexor pollicis longus).[30] Surgical techniques in this type of hand surgery are mainly the same for the different transfers.[30]

Technique for transferring the m. extensor carpi radialis longus: the m. extensor carpi radialis longus tendon is divided at its insertion on the second metacarpal. The muscle is separated, and freed entirely from the surrounding tissues. The m. extensor carpi radialis longus tendon is strongly attached to the planned tendon under maximum tension. The m. extensor carpi radialis longus can be transferred to the flexor digitorum profundus or flexor pollicis longus.[30]

Technique for transferring the m. brachioradialis: The brachioradialis is freed entirely from the surrounding tissues up to the elbow to get extra excursion. The brachioradialis tendon is strongly attached to the planned tendon.[30]

Rehabilitation

The post-operative regimens depend on the surgical procedures used. However, they tend to constrain the tetraplegic patient considerably. During most regimens they are not allowed to drive hand-driven wheelchairs, or to make transfers alone, because of the risk of rupturing a tendon suture.

In general the elbow extension reconstructions are immobilised for a few weeks and then slowly allowed to flex the elbow in the following weeks, at a rate of 10 degrees per week. After 10 weeks the patient is allowed to move freely again.[30]

After the posterior deltoid-triceps transfer, a cast is applied with the elbow at 10 degrees of flexion. The cast should be worn for 4 to 6 weeks and then exchanged for an elbow brace with an adjustable range of motion.[35]

After the biceps-to-triceps surgery the patient’s arm is immobilized for 3,5 weeks in slight flexion, this only counts for patient who could fully extend their arm before the operation. Otherwise the patient is immobilized in maximum extension and casted. This stays on for 10–14 days and a second cast is applied in further extension. After the immobilization the patient is given a protective polyaxial brace, which allows the patient to begin active limited flexion and still keep the full extension. This brace is worn by day and at night the patient wears a semi-firm splint that keeps the arm in maximal extension.[25]

With the emergence of the one step procedures for the hand, the post-operative rehabilitation programmes became even more important, since early movement is essential. Patients are mobilised 24 hrs post-operatively, with protective splints. The regimen takes approximately 12 weeks, before the hand is allowed to be fully loaded. Patients are not required to stay as an in-patient for the entire regimen, but can be treated as an outpatient after 1–4 weeks, depending on the centre where the procedures are performed.

References

- Pinch and elbow extension restoration in people with tetraplegia: a systematic review of the literature; Cynthia Hamou, et al., JHS vol 34A April 2009

- Opinions on the treatment of people with tetraplegia: Contrasting perceptions of physiatrists and hand surgeons; Catherine M. Curtin et al., J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30:256–262

- General indications for functional surgery of the hand in tetraplegic patients; Yves Allieu, Hand Clin 18 (2002) 413–421

- Current concepts in reconstruction of hand function in tetraplegia; J Friden, C Reinholdt, Scandinavian journal of surgery 97:341–346, 2008

- The upper limb in tetraplegia: a new approach to surgical rehabilitation. Moberg E., Stuttgart, Germany: George Thieme; 1978.

- Development of useful function in the severely paralyzed hand. Nickel VL, Perry J, Garret A., J Bone Joint Surg 1963;45:933–52.

- Providing automatic grasp by flexor tenodesis. Wilson JN., J Bone Joint Surg Am 1956;38:1019–24.

- Restoration of finger function by poliomyelitis. Irwin CE, Wray JC., J Bone Joint Surg Am 1957;19:716.

- Finger flexor tenodesis. Street DM, Stambaugh HD., Clin Orthop 1959;13:155–63.

- Structural and dynamic bases of hand surgery, 2nd ed. Zancolli EA., Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1979

- Structural and dynamic bases of hand surgery, 1st ed. Zancolli EA., Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1968.

- Surgery of the quadriplegic hand with active strong wrist extension preserved. Zancolli EA., A study of 97 cases. Clin Orthop 1975;12:101–13.

- Restoration of strong grasp and lateral pinch in the tetraplegic due to cervical spinal cord injury. House JH, Gwathmey FW, Lundsgaard DK., J Bone Joint Surg Am 1976;1:152–9.

- Two-stage reconstruction of the tetraplegic hand in master techniques in orthopaedic surgery. House JH, Walsh T., In: Strickland JW, editor. The hand. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998.

- Transfer of the brachio radialis to improve wrist extension in high spinal cord injury. Freehafer AA, Mast WA., J Bone Joint Sur Am. 1967;49:648–52.

- Tendons transfers to improve grasp after injuries of the cervical spinal cord.Freehafer AA, Vonhaam E, Allen V., J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56:951–9.

- The physiological method of tendon transplantation. I. Historical: Anatomy and physiology of tendon., Mayer L. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1916;22:182–97.

- The Moberg deltoid-triceps replacement and key-pinch operations in quadriplegia: preliminary report experiences., Bryan RS. Hand 1977;9:207–14.

- Restoration of elbow extension power in the tetraplegic patient using the Moberg technique., DeBenedetti M. J Hand Surg 1979;4:86–9.

- Surgical treatment for absent single-hand grip and elbow extension in quadriplegia. Principles and preliminary experience. Moberg E. J Bone, Joint Surg 1975;57A:196–206.

- Transposition of the biceps brachii for triceps weakness., Friedenberg ZB. J Bone Joint Surgery Am. 1954;36:656–8.

- Structural and dynamic bases of hand surgery, 2nd ed. Zancolli EA., Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1979.

- History of surgery in the rehabilitation of the tertaplegic hand; Eduardo A Zancolli, Hand Clinics 18 (2002) 369–376

- Use of intrinsic thumb muscles may help to improve lateral pinch function restored by tendon transfer; Joseph D. Towles et al., Clinical Biomechanics 23 (2008) 387–394

- Biceps-to-Triceps Transfer Technique; Ryan D Endress and Vincent R Hentz, J Hand Surg Am 2011 vol. 36 (4) pp. 716-721

- Biceps-to-Triceps Transfer for Elbow Extension in Persons With Tetraplegia; Scott H. Kozin, Elsevier

- http://www.asia-spinalinjury.org

- Clinical and radiographic evaluation of surgical reconstruction of finger flexion in tetraplegia; Arvid Ejeskar et al., J Hand Surg 2005;30A:842–849

- Choice-Based Evaluation for the Improvement of Upper-Extremity Function Compared With Other Impairments in Tetraplegia; Govert J. Snoek et al., Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;86: 1623–30

- Tendon transfers as applied to tetraplegia; Marc Revol, et al., Hand clin 18 (2002) 423–439

- Principles of tendon transfers to the hand; Smith RJ, Hastings H, AAOS Instructional Course Lectures 1993;21:129– 149

- How musculotendon architecture and joint geometry affect the capacity of muscle to move and exert force on objects: a review with application to arm and forearm tendon transfer design; Zajac FE, J Hand Surg 1992;17A:799–804.

- Upper limb reconstruction in quadriplegia: functional assessment and proposed treatment modification; Hentz VR, Brown M, Keoshian LA., J Hand Surg [Am]. 1983;8:119Y131

- A new surgical technique to correct triceps paralysis; Castro-Sierra A, Lopez-Pita A, Hand. 1983;15(1):42Y46.

- Posterior Deltoid-to-Triceps Tendon Transfer to Restore Active Elbow Extension in Patients With Tetraplegia; Cale W. Bonds and Michelle A. James, Tech Hand Surg 2009;13: 94Y97

- Field-Fote. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation.