Vertex (curve)

In the geometry of planar curves, a vertex is a point of where the first derivative of curvature is zero.[1] This is typically a local maximum or minimum of curvature,[2] and some authors define a vertex to be more specifically a local extreme point of curvature.[3] However, other special cases may occur, for instance when the second derivative is also zero, or when the curvature is constant. For space curves, on the other hand, a vertex is a point where the torsion vanishes.

Examples

A hyperbola has two vertices, one on each branch; they are the closest of any two points lying on opposite branches of the hyperbola, and they lie on the principal axis. On a parabola, the sole vertex lies on the axis of symmetry and in a quadratic of the form:

it can be found by completing the square or by differentiation.[2] On an ellipse, two of the four vertices lie on the major axis and two lie on the minor axis.[4]

For a circle, which has constant curvature, every point is a vertex.

Cusps and osculation

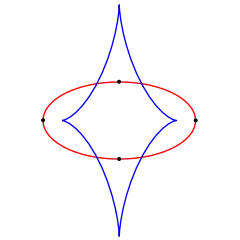

Vertices are points where the curve has 4-point contact with the osculating circle at that point.[5][6] In contrast, generic points on a curve typically only have 3-point contact with their osculating circle. The evolute of a curve will generically have a cusp when the curve has a vertex;[6] other, more degenerate and non-stable singularities may occur at higher-order vertices, at which the osculating circle has contact of higher order than four.[5] Although a single generic curve will not have any higher-order vertices, they will generically occur within a one-parameter family of curves, at the curve in the family for which two ordinary vertices coalesce to form a higher vertex and then annihilate.

The symmetry set of a curve has endpoints at the cusps corresponding to the vertices, and the medial axis, a subset of the symmetry set, also has its endpoints in the cusps.

Other properties

According to the classical four-vertex theorem, every simple closed planar smooth curve must have at least four vertices.[7] A more general fact is that every simple closed space curve which lies on the boundary of a convex body, or even bounds a locally convex disk, must have four vertices.[8] Every curve of constant width must have at least six vertices.[9]

If a planar curve is bilaterally symmetric, it will have a vertex at the point or points where the axis of symmetry crosses the curve. Thus, the notion of a vertex for a curve is closely related to that of an optical vertex, the point where an optical axis crosses a lens surface.

Notes

- Agoston (2005), p. 570; Gibson (2001), p. 126.

- Gibson (2001), p. 127.

- Fuchs & Tabachnikov (2007), p. 141.

- Agoston (2005), p. 570; Gibson (2001), p. 127.

- Gibson (2001), p. 126.

- Fuchs & Tabachnikov (2007), p. 142.

- Agoston (2005), Theorem 9.3.9, p. 570; Gibson (2001), Section 9.3, "The Four Vertex Theorem", pp. 133–136; Fuchs & Tabachnikov (2007), Theorem 10.3, p. 149.

- Sedykh (1994); Ghomi (2015)

- Martinez-Maure (1996); Craizer, Teixeira & Balestro (2018)

References

- Agoston, Max K. (2005), Computer Graphics and Geometric Modelling: Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 9781852338176.

- Craizer, Marcos; Teixeira, Ralph; Balestro, Vitor (2018), "Closed cycloids in a normed plane", Monatshefte für Mathematik, 185 (1): 43–60, arXiv:1608.01651, doi:10.1007/s00605-017-1030-5, MR 3745700.

- Fuchs, D. B.; Tabachnikov, Serge (2007), Mathematical Omnibus: Thirty Lectures on Classic Mathematics, American Mathematical Society, ISBN 9780821843161

- Ghomi, Mohammad (2015), Boundary torsion and convex caps of locally convex surfaces, arXiv:1501.07626, Bibcode:2015arXiv150107626G

- Gibson, C. G. (2001), Elementary Geometry of Differentiable Curves: An Undergraduate Introduction, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521011075.

- Martinez-Maure, Yves (1996), "A note on the tennis ball theorem", American Mathematical Monthly, 103 (4): 338–340, doi:10.2307/2975192, JSTOR 2975192, MR 1383672.

- Sedykh, V.D. (1994), "Four vertices of a convex space curve", Bull. London Math. Soc., 26 (2): 177–180